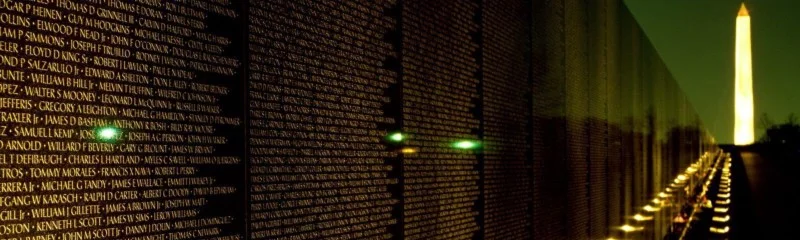

This weekend will mark the celebration of Memorial Day in the United States. It’s a time to remember veterans who died for their country, but it should also be a time to ask what their service accomplished. War, with all of its horror, must have a compelling purpose, and the only worthwhile intent is to create a better peace. Unfortunately, the peace generations of veterans fought for is fragile, and must be carefully preserved.

The True Meaning of Memorial Day

Most vets appreciate being thanked for their service, but if it happens on Memorial Day, there are many that will tell you to be thankful instead for those that never made it home. Memorial Day, celebrated at the end of May every year, is meant to remember them, our comrades-in-arms, that gave the ultimate sacrifice. After 20 years in uniform, Memorial Day means more to me (and many veterans like me) than it might to other Americans.

Scarcity as a Source of Violent Conflict

Scarcity should both interest and scare strategists and policy makers. It refers to a mismatch between the demand for and availability of a commodity. It helps drive free markets, and informs value. But strategists and policy makers should contemplate it because scarcity, both real and perceived, drives much of human conflict, and it has reared its head again, this time in Yemen.

Army-Air Force Talks

Dan and Dave, no relation to the famous Olympic decathletes, began a dialogue following a workshop on the development of an Air Force Operating Concept. At the conclusion of day 1 of the workshop, Dan and Dave had a discussion on the future of the military; to include the direction our respective services are headed. The idea popped up that these deep discussions should be published, for others to read and debate. The richness and value of discussions on the future of warfare is worthless if left between two people.

We know how to strike, but can we achieve victory?

The U.S. military has been, without a doubt, innovative during the past century of warfare. Advances in technology have allowed the U.S. armed forces to become the most expeditionary, precise, and lethal force in the world. During the Cold War, the bulk of defense spending went towards countering the Soviet threat. In the end, the strategy was a success; the Soviet Union fell without direct confrontation. In the meantime, the U.S. military’s culture adapted to the political and economic realities of the Cold War. Although the Cold War has technically been over for 25 years, elements of that era’s defense culture have proven extremely resistant to change.

The Human Costs of War: Justin Miller’s Story

Bad Intelligence and Hard Power

If you are invested in defending torture on the basis of its potential utility, it would be prudent to frame the issue by claiming that the torture of captured extremists has led to useful intelligence. That way, your detractors will respond either by arguing that torture did not lead to useful actionable intelligence, or that torture is ethically unjustifiable even if it is a useful method of information gathering. Either way, the pro-torture argument comes out ahead — because given this way of framing the issue, the worst-case scenario is that torture is ineffective and unethical. But, in fact, that is not the worst-case scenario. There is a scenario far worse even from the most utilitarian point-of-view — a scenario involving bad intelligence.

In the Information Age Centers of Activity > Centers of Gravity

After the 1991 Gulf War, the character of war changed dramatically, and not in the way America believed it would. While spell-binding CNN footage sold us on the value of precision attack, our adversaries across-the-board learned two very different lessons. First, if it matters, it has to move and hide. Second, reclaiming the initiative from the US is always possible, as Iraqi SCUDS nearly proved. Their new playbook was clear — absorb, re-form, and reengage. Shock and Awe had its moment, but is gone for good. That is, unless we shift away from the idea we can take down a resilient, adaptive system by attacking centers of gravity, and instead harness our ability to observe and affect a system’s centers of activity.

Achilles and Odysseus in Modern Warfare

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to warfare. One is to be strong and powerful. The other is to be smart and cunning. The Greek terms for these concepts are biē and mētis respectively. In The Iliad and The Odyssey, Achilles personifies biē, and Odysseus embodies mētis. The United States military can and should learn a lesson about its operational art from the lives of the two mythological warriors.

Narrative: Everybody is talking about it but we still aren’t sure what it is.

In his 2009 work, The Accidental Guerrilla, David Kilcullen summed up the different communication approaches by Al Qaeda-backed insurgents and the Western-led Coalitions seeking to defeat them. “We use information to explain what we’re doing on the ground. The enemy does the opposite — they decide what message they would send and then design an operation to send that message.” The observation was not new; it had been described in similar fashion among the Strategic Communication and Information Operations community since the commencement of the Global War on Terror and earlier and is often referred to as “narrative-led operations.” Kilcullen did however bring the concept to main-stream military thinking.

This Anzac Day: Defining the Contemporary Veteran

Author's Note: This post flows from thoughts during Anzac Day and from reading James Brown’s book Anzac’s Long Shadow.

Today is Anzac Day, the day of the ‘exceptional digger’[1] and time to reflect on wars past. It is a curious day for those of us with recent operational experience as our part in Anzac Day commemorations is yet to be precisely defined.

Photo by Neil Ruskin, Afghanistan 2008

Contemporary veterans are a diverse group with no ingrained stereotype. Some are still serving military members and will march in today’s Anzac parades with their units. Others have transitioned to civilian life and may march under an ex-services banner. Some will opt to stand undetected on the sidelines while others who hold painful memories of war may wish the day was not filled with military reminders. So how does the stereotype of ‘Anzac’ and ‘veteran’ compare alongside the mould of our most recent veterans this Anzac Day?

Anzacs and veterans

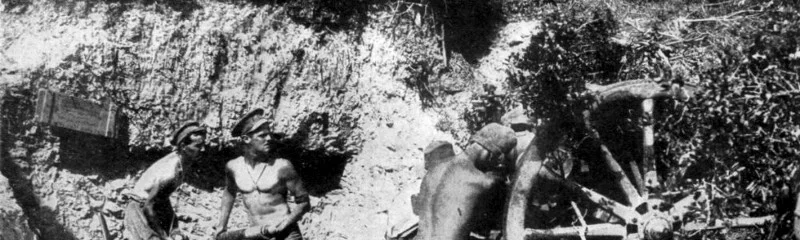

The image conjured when I think of Anzac is that of rugged men muddied in trenches. They stare out at you from history books with toughness, resilience and bashful courage. Their knowing eyes defy their youthful faces. Anzac is the image of our past and provides the foundation for our present.

Photo by Mark Brake, The Advertiser

The image of a veteran, to me, has always been my grandfathers. Both served in World War II, one Army and the other Air Force. Their tales from Papua New Guinea, Britain and Burma were lost with their passing some years ago as neither shared their war stories when alive. As they reached the end of their lives their decrepit features mirrored those often flashed up on screens during Anzac Day — that of aged men with worn medals clanking across their now deflated chests. This vision of veteran is often shown with the dichotomy of youth; an iconic visual of the veteran’s actions and sacrifice as legacy to future generations. Their youthful faces passed onto the next generation but without the toughened glare of war.

I only had one fleeting moment of conversation with each of my grandfathers about their roles in World War II. War was rarely discussed. The first was with my grandfather who served in Papua New Guinea. I was 20 years old and had just completed Exercise Shaggy Ridge[2] (a sleep and food deprivation training exercise) as a cadet at the Royal Military College Duntroon. I was proud I had completed the arduous activity when others hadn’t. My grandfather paused in his response to my story, “Shaggy Ridge, yes, I patrolled in that area. I was so bloody scared of heights that I was more afraid to look down than I was of the Japs”. This ephemeral exchange of stories with a World War II veteran forever put my Army warries back in the box.

The second exchange was with my grandfather who served in the Air Force. I was about to deploy on my second tour of Afghanistan and was visiting him during pre-deployment leave. I chatted about my first deployment to Afghanistan and explained how my second deployment would be similar. During the conversation my grandfather disappeared. A couple of hours later he re-emerged holding two photographs. The first was a photograph of him in Afghanistan, taken while he was transitioning from Britain, where he had been a Night Intruder, to the campaign in Burma. “Afghanistan’s pretty rough, don’t trust the locals in a card game, they slit a chap’s throat when he didn’t pay his debt”. Handy advice. The second was a photograph of his Flight taken in Britain. For all bar two, the word ‘dead’ or ‘maimed’ was bluntly stated as he pointed at their youthful faces. I’m grateful one of the two was a younger image of my grandfather. With the words “war’s not the same anymore”, he disappeared again. This grandfather never attended Anzac Day.

I will never know the rest of my grandfathers’ stories but they will always be my image of a veteran and what I personally remember each Anzac Day. I cannot change my own stereotype image of Anzac and veteran. The textbook definition of a veteran may be simple but having a sense of being a modern veteran is a little more complicated when analysed against the past and ingrained stereotypes. The word veteran may never sit comfortably with me when pointed in my direction.

Who we are and who we are not

This morning the song ‘And the band played Waltzing Matilda’ rang out at my Regiment’s Dawn Service. Images of frail aged men once again flashed up on an overhead screen as the song struck the words:

“But the band plays Waltzing Matilda, and the old men still answer the call. But as year follows year, more old men disappear. Someday no one will march there at all.”[3]

But there will be someone. They are the contemporary veterans.

My thoughts coincide with reading James Brown’s book Anzac’s Long Shadow. Brown, a contemporary veteran himself, has eloquently captured the thoughts of many of us who are struggling to define ourselves against the Anzac stereotype.

Against another era of veteran, contemporary veterans do not face the Vietnam veteran’s adversity of returning to a nation that scorned their deeds. Our return has the support of the broader Australian community. We also have a blank canvas for our image. Brown points out that little is known in the general Australian community about the role of Australian Defence Force personnel in recent conflicts including East Timor, Iraq, Afghanistan and Solomon Islands.

Indeed serving personnel sometimes have misconceptions of veterans. During Anzac Day in 2011 I overheard an Australian Army soldier question why a member of the Royal Australian Navy was wearing an Afghanistan Campaign Medal. The tone suggested unworthiness of the honour; Afghanistan after all is a land-locked country. I was affronted by this comment as I had deployed to Afghanistan with Navy personnel who were Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technicians and Airforce personnel who were Joint Terminal Attack Controllers. If you know what these roles are, you will know how much admiration I have for their courageous service and contribution to the survivability of our team. As I explained to the soldier — even though medals look the same, each medal comes with its own story. Every contemporary veteran’s contribution should be valued without judgement.

Photo by Neil Ruskin, Afghanistan 2008

Similar stories are also presenting. Women are often judged to have only completed sedentary roles in Afghanistan and Iraq when there are many examples of the opposite. I have had young sappers tell me they have attended RSLs (Returned & Services Leagues) on Anzac Day and been told to move their medals to their right side as ‘don’t you know, medals awarded to a family member go on the right side of your chest’. Someone needs to remind these self-appointed hall monitors that the sentiment of the song ‘I was only 19’ applies not only to wars of bygone eras but also to our most recent conflicts. Having to justify your medal and convince people of the violence you faced in conflict because of your gender, age, service or corps is something I hope is a passing fad. This is a dangerous form of stereotyping that may become ingrained if our stories are not shared.

I don’t have a definition for the contemporary veteran or what mould we are made from. The lack of a stereotype may be our defining feature in the end. What I do know is that we own the image of the contemporary veteran because we are the contemporary veteran. We should not sit passively by and let others define who we are or who we are not. If we don’t own the image of the modern-day veteran then someone else will define it for us. This is clearly evident in the United States where tragic events inflicted by one have led to the stereotyping of many (see here, here and here). Brown calls for proactive participation of serving members in intellectual debate and the “fluid exchange of ideas and the honest and intelligent study of the past”[4]. Reflecting on our own contribution to the past and its meaning to our future may be a good place to start.

I caveat this call for action. There is no romanticised version of war, and men and women sign up to protect the general community and their loved ones from the horrors of war. It is difficult to share the horrors with people outside the military fold when it is those people who you served to keep the horrors from. Some contemporary veterans might not be ready to share. Like my grandfathers, the time may never come when the stories flow in general conversation. It is in this space that the voice of other veterans becomes ever more important.

To me the words veteran and Anzac conjure images of courageous men. Those men who returned home are now wearied by age and those who did not return home are forever suspended in youth. It is the spirit of Anzac and actions of veterans past that found the human qualities of the contemporary veteran — qualities of mateship, resilience and courage. They give meaning to our present and a reassurance in our human spirit for the adversities of the future. With this foundation and remembrance it is time for contemporary veterans to define our own image.

Major Clare O’Neill served in Afghanistan in 2006 and 2008. She is currently an Officer Commanding at the 3rd Combat Engineer Regiment, Australian Army.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Brown, James, Anzac’s long shadow: the cost of our national obsession, Redback, Collingwood, 2014, p. 96.

[2] Exercise Shaggy Ridge is named after operations in the forenamed area in Papua New Guinea in World War II, seehttp://www.awm.gov.au/units/event_347.asp

[3] Bogle, Eric, And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda, Larrikin Music Pty Limited, Sydney.

[4] Brown, p. 105.

Originally published at groundedcuriosity.com.

The Battle of Gallipoli

The Battle of Gallipoli was a watershed moment in the history of warfare. Few other battles were initiated with such high strategic hopes that were then dashed so quickly. Its influence carried far beyond the war in which it occurred. Simultaneously, it spurred some observers to proclaim that the amphibious assault was impossible and others, notably then-Captain Earl “Pete” Ellis of the United States Marine Corps, to completely reexamine the amphibious assault in a modern context and design modern forces to accomplish it.

Teaching Tacticians: #Reviewing Naval Tactics

How do you win? Strategists determine what must be done and why. Operational planners devise the when and where. Tacticians are left the most daunting question: How? Though tactical prowess cannot save a poor strategy, the success of both strategy and operational planning frequently ride on tactical achievement. Yet, unlike strategy, tactics are infrequently discussed. Many tactics hide behind layers of classification, and training commands train their students to memorize and execute “proven” “pre-planned responses.” In the exigencies of combat, muscle memory is critical, but discussion of how those tactics were proved is often lost.

These problems are particularly acute for naval tactics. No two navies have fought a major fleet engagement in more than seventy years, and those who would command ships in battle must wait until the twilight years of their careers before they can coordinate multiple units. The U.S. Naval Institute’s new Naval Tactics “wheel book” helps fill a yawning gap.

Unlike much rote tactical training, the book highlights the role of thinking and experimentation, particularly qualitative, historical study.

Edited by Captain Wayne Hughes, USN (ret.), Naval Tactics includes tactical essays from the past 110 years. Hughes highlights directly applicable tactical principles, such as continuing importance of tactical formations, as well as the drivers of tactical change while providing subtle comment on some of the most important challenges facing the U.S. Navy today. Many essays remain as relevant today as they were when written, 30 or more years ago. Unlike much rote tactical training, the book highlights the role of thinking and experimentation, particularly qualitative, historical study.

One might expect that Hughes, an operations researcher, would emphasize quantitative methods in developing and testing new tactics. He argues, however, that tactics require a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis, or art and science, as he terms them: “The value of science is illustrated by operations analysis and quantitative calculations while the role of art is illustrated by the unique insights of great leaders who could reduce complex considerations into clear and executable battle plans.”[1] The books emphasis on qualitative analysis is striking. Of its thirteen essays, only the oldest, a selection from Bradley Fiske’s “American Naval Policy,” contains any discussion of quantitative calculations.

This imbalance likely targets the intended audience, few of which will have operations analysis experience and many of whom may have no prior tactical education. Even so, it seems significant that as a tactical primer the book focuses on the art rather than the science of tactics, particularly when that art is presented as the stuff of “unique insights of great leaders.” Such insights are as likely the product of preparation and study as of inborn ability. The book’s existence presupposes one can learn to think tactically.

Hughes frequently omits the tactical conduct of a battle from his selections, focusing instead on the preparation for battle or the development of the tactics it would see employed.

In pursuit of that goal, the book clearly emphasizes rigorous historical study in combination with thought experiments. Eight of Hughes’s thirteen elections detail historical battles or the history by which a tactic was developed. Two of the remaining essays (the opening and closing) layout thought experiments. Surprisingly, Hughes frequently omits the tactical conduct of a battle from his selections, focusing instead on the preparation for battle or the development of the tactics it would see employed. This choice emphasizes the contingency of outcomes and further supports the importance of principles of thought.

Ultimately, the commander must be able to act and react in the moment of battle. In the words of Frank Andrews, when “two pieces of war hardware … are roughly on a par, … the victor will be determined only by the outcome of the clash between the minds and the wills of the two opposing commanding officers.”[2] Here, numerical analysis breaks down, for while aggregate probabilities may suggest what generally works, the commander must determine the best course of action for his or her particular situation. Some officers may be born with talent, but for most no substitute exists for practice and study in developing the perspective and judgment required for making tactical decisions.

Without a doubt, combat experience teaches tactical thinking most effectively, but mistakes are costly and opportunities thankfully rare. Exercises provide the next best option. Although, Navy devotes more time to exercises today than it did when Bradley Fisk called for competitive “sham battles” to improve tactical performance over 100 years ago, the chances for practice remain few.[3] Only the study of past battles, the principals they illuminate, and the discussion of the questions they stir, remains as an inexpensive and widely accessible option.

Operators will always highlight experience when finding ways to win, but too often today’s Navy eschews the investment in study that can prepare officers to take full advantage of operational opportunities. The selections and stories in Naval Tactics provide an excellent and engaging place to begin such study.

Erik Sand is an active duty U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer stationed at the Pentagon. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Wayne P. Hughes Jr., ed., The U.S. Naval Institute on Naval Tactics, U.S. Naval Institute Wheel Books (Annapolis, MD: naval Institute press, 2015), xii.

[2] Hughes, Naval Tactics, 53.

[3] Hughes, Naval Tactics, 108.

Beyond Great Men & Great Wars

Finding Wisdom in the Spaces in Between

In the 1840s, Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle wrote that “the history of the world is but the biography of great men.”

This statement is a summary of the sharply criticized and deeply problematic Great Man Theory which nonetheless continues to pervade how we teach, and therefore understand, history. Simplistic as the theory is, and despite falling from favor among historians after World War II, history is still largely taught by jumping from great man to great man, major event to major event. AP US History students are shepherded through the dawn of the 20th century, World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II as the highlights of a single historical period (beware, link contains comic sans).

What could be called a military corollary to the Great Man Theory was recently explored by Angry Staff Officer, who used the language of land navigation to note that “when the Army, and by definition those in it, looks at its history, it tends to reflect on its own significant terrain features, i.e., wars.”

The problem, though, is that history does not stop between wars. Indeed, sometimes what wins wars are the reforms that take place in inter-war periods. While it is sometimes tempting to skip over the boring periods, those often contain gems that can help us relate to our own time.

Between major terrain features—great men and great wars—hide the driving forces of history. Angry Staff Officer discovered surprisingly relevant gems on leadership, budgets, and force reductions in “an edition of the now-defunct “Coast Artillery Journal,” of the even more defunct Coast Artillery Corps.”

I once came across an gem in an otherwise “boring” interwar area—1930s congressional committees and hearings—which has only become more interesting with time.

Trick question: What congressional special committee held over 90 hearings, calling more than 200 witnesses, over a two year period, and found very little hard evidence of an actual conspiracy?

.

..

….

…..

……

…….

Nope, not #Benghazi.

While it seems that the Benghazi hearings will never end, modern Congressional Republicans have not entirely eclipsed the dirt-digging of the 1930s. In May 2014, Politico lamented that the “wide-ranging probe,” a series of investigations by several different House and Senate committees, “has already spanned 13 hearings, 25,000 pages of documents and 50 briefings.”

The 1934–36 Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, better known as the Nye Committee (named so after its chairman, Republican Senator Gerald Nye of North Dakota) consisted of over 90 hearings conducted over two years, calling on more than 200 witnesses including J. P. Morgan, Jr. and Pierre du Pont. The investigation, which focused on the munitions industry, bidding on government shipbuilding contracts, war profits and the eventual US entry into World War I, ended abruptly in early 1936 when Nye stepped out of bounds and suggested that President Woodrow Wilson had withheld information from Congress as it considered the 1917 declaration of war against Germany.

Although the committee fell short of its aim to nationalize (and thereby reign-in) the arms industry, it fundamentally inspired the Neutrality Acts of 1935, 1936, 1937, and 1939 which delayed American entry into World War II and is largely cited as a core reason the US was unprepared for the war.

In 1961, President Eisenhower summarized the military-industrial complex in his farewell address. Eisenhower, in a powerful and meaningful speech, said that “until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry” and that the “conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry” was new to the American experience. He was somewhat wrong. While the arms industry by the 1960s vastly outpaced any period before, as did the the overt participation of the government in arms development, a noting of complex interrelationship between technological progress, the arms industry, and the American military machine can be seen much earlier in the pages of the Nye Committee’s 1936 report.

The report goes beyond merely accusing munitions companies of bribery to note that

…the very quality which in civilian life tends to lead toward progressive civilization, namely the improvements of machinery, has been used by the munitions makers to scare nations into a continued frantic expenditure for the latest improvements in devices of warfare. The constant message of the traveling salesman of the munitions companies to the rest of the world has been that they now had available for sale something new, more dangerous and more deadly than ever before and that the potential enemy was or would be buying it.

The Nye Report paints a complex picture depicting the interplay between war, politics, and business that Eisenhower later called attention to. Eisenhower certainly said it best, but he did not say it first.

Nye Report, 1936: “The committee finds, further, that the constant availability of munitions companies with competitive bribes ready in outstretched hands does not create a situation where the officials involved can, in the nature of things, be as much interested in peace and measures to secure peace as they are in increased armaments.”

Eisenhower, 1961: “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

“…it seems to me that any study of the Munitions Investigation requires first of all a real comprehension of the tempers, tone, spirit of the country at the time…”

Dorthy Detzer, peace activist and ironically, given the large defense industry lobby today, a lobbyist.

Writing about the Nye Committee in 2009 as an undergraduate history student, I became fascinated by a quote from Dorothy Detzer in a letter to historian John E. Wiltz. Detzer, a peace activist rarely mentioned in textbooks alongside the committee was the behind-the-scenes driving force in its creation and ultimate direction. In a 1960 letter to Wiltz, Detzer wrote that “…it seems to me that any study of the Munitions Investigation requires first of all a real comprehension of the tempers, tone, spirit of the country at the time…”

The first World War, at the time called simply the Great War, ended 16 years before the investigation. It was an immediate memory for the American public, who had lived through the war, and served as the temporal grounding point for the investigation. In addition, the Great Depression engendered a broad anti-business sentiment in the public sphere. The Great War and the Great Depression marked the temper and tone of the time, and the spirit was born from the outrage of peace activists and machinations of isolationist politicians who suspected that those who profited from war could very well be interested in it occurring more frequently.

The spirit of 1934 is a small ghost wandering the pages of interwar history, a forgotten child of the “Great War” and the Great Depression. She reminds us that history is not only a cast of great men conducting a series of great wars, but also a multitude of bit parts, played by dickering politicians, lobbyists, and a public swayed by time and temper.

Angry Staff Officer concluded that “it might behoove leaders and historians alike to look away from the dramatic terrain features of history and instead examine some of the paths less trodden.”

He couldn't be more right. You’d be surprised what can be found by looking into defunct journals and old committee reports, and astounded by the lessons we can learn by peering into the shadows of great men and great wars.

Catherine (Katie) Putz is the special projects editor at The Diplomat. She studied American conflict & diplomatic history and then ran off to Kentucky to study international security. She writes about foreign policy, national security, and countries that end in -stan, among other things.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The Movement that Seeks a State

Though much ink has already been spilled regarding the Islamic State’s theology, it is important to place this group within the wider movement of political Islam that emphasizes Salafism. Salafism has a lengthy history, and has been mustered to support nationalistic insurgencies as well as transnational terrorist networks well before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. While the tenets of Salafism are deceptively simple, the implementation of these ideas varies greatly.

To call this simply a religious matter neglects the clear manipulation of religion by some Salafist movements for political purposes. At the same time, to ignore the theological undertones in these movements risks missing key insights. The Islamic State is merely the latest network to appropriate Salafism. Prior to the Arab Spring, Al Qaeda was the most widely known Salafist group advocating anti-establishment upheaval. But it too, was not the first militant Salafist organization or movement. As the the Islamic State will not be the last. Analyzing the ideological underpinnings of these movements is vital to anticipating future challenges and opportunities. While militant Salafism is expanding in the region, there is also an expansion of Iranian supported Shia militias. These trends present a staggering risk for conflict, a fact that Western policymakers seem to want to ignore.

A Baseline of Understanding

Salafism is a religiously based sociopolitical movement that has generated numerous interpretations despite its apparently simple call to live like the first generation of Muslims. Salafists traditionally have been of the “quietist” variety, a term used by Joas Wagemakers to describe the movement’s focus onda’wah, or proselytizing. This quiet focus was adopted because of a perception that society was not yet prepared to return to the idealized sociopolitical practices of Prophet Muhammad’s and his followers. Quietist Salafists have also tended to support Muslim rulers, even autocrats with secular leanings.[1]This support stems from the belief that excommunication, takfir, of a fellow Muslim was such a serious matter that it should only be undertaken when absolutely certain. It was more prudent to point out a sinful act instead of accuse a fellow Muslim of infidelity.[2] These interpretations within Salafism were convenient for Muslim heads of state, providing flexibility with policy as long as some deference was provided to faith.

Sayyid Qutb (Wikicommons)

In response to repression and the perceived failings of secular statecraft, prominent Salafists started to challenge this apolitical interpretation. One of the most influential voices in this was Sayyid Qutb, who argued that Muslim rulers should be opposed, perhaps violently, because they were following secular forms of governance. He referenced back to Ibn Taymiyya, an important scholar during the Mongol era, who justified fighting Mongol invaders in the Arab world because these invaders maintained heretical practices despite converting to Islam. Using any form of worship or governance that was not expressly part of early Islamic teachings is considered by more radical Salafists to be a violation of the unity of God, as the sole spiritual and legal authority.[3] According to Qutb, referencing Ibn Taymiyya, it was acceptable to excommunicate Muslim leaders who replaced God’s legal authority with secular institutions. These ideas were seized upon by fellow Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri and the leadership of Al Qaeda. A similar interpretation of excommunication was developed by Ibn Wahhab, who was and remains influential in Saudi Arabia. His focus on apostasy further detailed practices that could also be considered heretical including prayer to saints or the adulation of shrines.[4] Quintan Wiktorowicz speculates that during the anti-Soviet conflict in Afghanistan, these two interpretations of apostasy were shared by Egyptian and Saudi militants, producing the theological beliefs of Al Qaeda.[5] Ibn Taymiyya’s interpretation of God’s sole authority in spiritual and political matters was influential in the anti-colonial rebellions of the nineteenth century in Pashtun lands as well. From these fighters and their theological interpretations, one can draw a direct link to the Deobandi school in Afghanistan and Pakistan as well as the writings of Qutb.[6]

Bin Laden’s command center in Pakistan (Wikicommons)

Salafist militants have also differed over launching defensive versus offensive operations, the targeting of civilians, and the acceptability of suicide attacks. Different groups have referenced different teachings or historical incidents to justify the applicability of their tactics and strategies. As a result of different emphasis on sources, there is a degree of interpretive flexibility in Salafist militancy.[7] Defensive jihad can be waged by a group without full authority over a territory or a people. Offensive jihad, on the other hand, requires the authority of a Caliph.[8] Al Qaeda has interpreted Salafism as justifying attacks against the secular regimes in the Islamic world as well as their enablers — the often cited near and far enemies. While Al Qaeda has an expansive view of acceptable civilian targets, the group has also been critical of too much violence directed against Muslims by militant Salafists.[9] Zawahiri advised the emir of Al Qaeda in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, to minimize casualties among the faithful and build an emirate which could one day potentially become a Caliphate. In Zawahiri’s interpretation of Salafism, targeting Shia was a mistake because the majority of them were innocents merely practicing the faith they had known all their lives. Ultimately, the Caliphate would be critical to uniting all Muslims under one authority and taking offensive actions against neighboring regimes as well as Israel.[10] The fissures between Zarqawi and Al Qaeda that played out during the US occupation of Iraq have ruptured once again. The organization that evolved from Zarqawi’s bloodthirsty rebellion has declared itself a Caliphate and as such demanded the obedience of the entire Muslim world.

Salafists are also learning that they need to find ways of developing popular support in order to increase the chance of success for these projects.

It is important to note before discussing this split in greater detail that militant Salafists are essentially arguing over the implementation of common principles. These factions do not object to the effort toward building Salafist states.[11] Opponents of the so-called Caliphate of the Islamic State argue that it lacks sufficient territory or clerical support to make such a bold declaration. There have been other state-building projects within the broader Salafist movement. No matter the fate of the so-called Islamic State, militant Salafists will continue to strive for the establishment of a state in the future. Salafists are also learning that they need to find ways of developing popular support in order to increase the chance of success for these projects.[12] Some quietists have broken with the apolitical nature of their interpretations and participated in elections. Setbacks for these democratic-Salafists, such as in Egypt, have encouraged more militant interpretations.

The differences between Al Qaeda’s and the Islamic State’s interpretations hinge largely on the scope of takfir. This and other differences have emerged among bin Laden’s network, but at times these differing groups have managed to work together as well. Western analysts must remember this when studying the latest trends within this movement. Zarqawi received funding from bin Laden and approval to open a training camp in Afghanistan. Zarqawi focused on the near enemy at a time when Al Qaeda targeted the far enemy. There have been numerous reports of some differences between the two, but the exact differences may never be known to us. Al Qaeda declared autocrats and institutions to be apostate, while Zarqawi was convinced that the Muslim world needed to be purged, bloodily, of apostate peoples.[13] Zarqawi’s training camps in Afghanistan included many former prisoners from Jordan.[14] His ideological severity seems more like the beliefs held by Abu Musab al-Suri, who thought that Al Qaeda camps lacked sufficient theological training in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[15] Suri, much like Zarqawi, operated in a semi-independent affiliation with Al Qaeda.[16] Al Qaeda saw itself as an anti-establishment Salafist vanguard, whereas Zarqawi saw his organization as fighting for a new establishment.[17]

Abu Musab al-Suri had links to the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria, which rebelled against the Alawite regime and was mercilessly squashed in the 1980s. Suri was trained in Egypt and in Iraq for the fight against Syrian President Hafez al-Assad. Even one of his Iraqi trainers had a direct link to Sayyid Qutb.[18] After the near destruction of the Syrian wing of the Muslim Brotherhood, Suri went to work with a radical propagandist, Abu Qatada. Qatada advocated the killing of rivals and their family members during the bloody conflict in Algeria, the same fight which gave members of Al Qaeda pause for the amount of Muslim bloodshed.[19] Qatada appears to have had ties with Zarqawi as well, as he provided the letter of introduction for Zarqawi in order to schedule a meeting with bin Laden.[20] In Afghanistan, Suri’s reputation was that of an extremist even among the militants. He killed individuals who wished to leave his group and advocated a wide interpretation of takfir, similar to the beliefs held by Zarqawi.[21] At least one follower of Suri, Amer Azizi, joined Zarqawi’s network in Iraq.[22]

Mugshot of Abu Bakr al Baghdadi (Wikicommons)

During the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, Zarqawi came to be one of the most infamous insurgent-terrorist commanders of the conflict. His network, which was merged eventually with the overall Al Qaeda organization, remains active in Iraq and Syria but has undergone a number of changes. The current leader of this network, now calling itself the Islamic State, was declared a Caliph last year. A decade before that title was claimed, he was a Sunni insurgent in an American run jail.[23] Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, now the so-called Caliph, was a key figure in the jail because he seemed to be able to maintain the peace among different factions, according to a fellow prisoner interviewed by The Guardian.[24] Baghdadi appears to have used his role as a “fixer” in the prison to build a greater power base. He held a PhD is Islamic studies and claimed descent from the Quraysh tribe, the same tribe as the Prophet Muhammad.[25] Prisoners developed more expansive networks in the massive jail and taught one another improved tactics.

A Caliphate Born in Prison

According to a secular Kurd who was a high-ranking member of Iraq’s Interior Ministry, the insurgency was significantly aided by the Syrian government in an attempt to discredit the US. As the insurgency faltered during the Sunni Awakening in 2008, Syrian officials met with the Salafists and coordinated with exiled Iraqi Ba’athist officials. Their machinations were introduced to the country when a series of massive bombings took place in Baghdad in the summer of 2009. Baghdadi rose to lead the descendent organization of Al Qaeda in Iraq in 2010 upon the death of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, who relied upon the Qurayshi PhD as a courier.[26] Two subsequent events would drastically impact the stability of the region. The US military withdrew from Iraq, leaving Nouri al-Maliki with significant control over the country’s fate, and the Arab Spring encouraged a largely Sunni rebellion against Bashar al-Assad, Hafez’s son.

Prior to the revolt against Bashar al-Assad, Salafism did not have many adherents in Syria. The fighting in the 1980s against the first Assad resulted in many deaths and the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria was ostracized.[27] A marginalized segment of the Sunni population would find Salafism appealing as the uprising spread in the wake of the Arab Spring. This segment was not closely tied to pro-government clerics, and was searching for an ideological justification for fighting back against the government’s increasingly brutal crackdown on dissidents. These presented opportunities for the first Salafist militant groups in the country, including Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham. More moderate members of the opposition were hoping to replicate the “Libyan model,” seeking international assistance in toppling the autocrat. When that assistance failed to materialize, Salafism and militancy were available as an alternative.[28] Jabhat al-Nusra was initially criticized for its use of violence, but soon adapted to gain more popular support among the opposition movements. Al Qaeda linked clerics endorsed this faction as the best Salafist militant group as well.[29] Jabhat al-Nusra seemed to be following Al Qaeda’s methodology by supporting other radical groups within a broader movement governed by consensus.[30] As Jabhat al-Nusra gained prominence, the Islamic State of Iraq announced that it was the force behind the group and attempted to assert control over the organization.[31]

At the end of 2013 and in the beginning of 2014, other rebel groups began to attack the Islamic State in western Syria, forcing the group to focus on the eastern part of the country adjacent to Iraq.[32] At the same time, the Syrian regime also began to focus more on the rivals to the Islamic State, providing an opportunity for Baghdadi’s group to consolidate in the East.[33] The Islamic State went so far as to kill the leader of Jabhat al-Nusra in Raqqa in December 2013.[34] In an attempt to unify Salafist groups in Syria, Zawahiri designated a long-time Al Qaeda associate as a mediator in the dispute. Abu Khalid al-Suri had a lengthy career with Salafist militancy and spent much of that time with Abu Musab al-Suri. As their noms de guerre indicate, both men were from Syria. Abu Khalid was a top commander in Ahrar al-Sham and may have been viewed by Zawahiri as a potential honest broker in the dispute.

The Islamic State’s history in Iraq demonstrates a willingness to assassinate rivals in order to consolidate power.

As Aron Lund points out, Abu Khalid had a more “nuanced” relationship with Al Qaeda than some reports indicate. His long affiliation with Abu Musab, including a stint rebelling against Hafez al-Assad in the 1980s, indicates that he was in fact not a part of Al Qaeda but would have worked alongside the group on numerous occasions. Both Abu Khalid and Abu Musab had ties with the Madrid 2004 bombing cell. His role in Ahrar al-Sham, and potentially his ties to Al Qaeda, had been minimized with an alternate nom de guerre prior to his designation as a mediator among militants.[35] Nonetheless, Abu Khalid was a bona fide Salafist militant and terrorist committed to a largely compatible interpretation of Salafism as that held by Al Qaeda. He along with another commander were killed in early 2014. Ahrar al-Sham has accused the Islamic State of orchestrating the attacks, although there has been no claim of responsibility. The Islamic State’s history in Iraq demonstrates a willingness to assassinate rivals in order to consolidate power.

Finding Allies

Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) have long had a dubious relationship with Shia militias.[36] These militias, long supported by Iran, were responsible for death squads that killed thousands of Sunnis during the US occupation.[37] As the US withdrew from Iraq, Maliki sought to monopolize control of the security establishment. Politically motivated prosecutions were leveled against prominent Sunni officials in the government, forcing some to flee.[38] The government also would not integrate the militias from the Sunni Awakening, which had fought against Al Qaeda in Iraq, into the state’s security apparatus. However, even some of the most terrible Shia militias were integrated into the government’s security forces. Demonstrations were held in response to these policies in Sunni regions of Iraq. In the spring of 2013, government forces killed demonstrators in Hawija. Sunni politicians that remained involved with the central government immediately lost standing within their communities. Increasing sectarian violence in 2013 provided an opportunity for the Islamic State to reassert its control in Sunni areas of Iraq.[39] Initially, the Islamic State would work with other insurgent groups, but after government forces were routed the Islamic State would consolidate power either by expelling rivals or killing them.[40]

By establishing a Caliphate, the Islamic State was attempting to demand obedience from all Muslims in the world.

As the conflict in Iraq escalated, Maliki portrayed the clash in sectarian terms, even going so far as to suggest that the direction of the qibla shift from Mecca to Karbala.[41] This statement is impossible to overemphasize. The Prime Minister of Iraq was advocating a shift in the focus of daily prayer to an important city in Shia Islam. The Islamic State, with a unified territory along the borders of Syria and Iraq, asserted that it was now a Caliphate. By establishing a Caliphate, the Islamic State was attempting to demand obedience from all Muslims in the world. The Caliphate likely was also a strategically timed declaration in the ongoing conflict within Salafist militant groups as well as a way to continue attracting recruits. Increasingly radicalized actions and rhetoric within the region have also likely influenced this decision. This state-building project had been tried by the followers of Zarqawi before.

Some within the Islamic State thought claim of statehood in 2006 was too premature, attempting to overcome battlefield weakness with a proclamation they were not yet ready to realize.[42] The Islamic State gained a significant infusion of fighters after the declaration of a Caliphate.[43] The group has also emphasized the provision of social services within territory it controls, indicating that the group has learned from its first state-building efforts in 2006 and 2007.[44] The Islamic State is also trying to recruit and utilize more skilled individuals as it takes over state institutions in areas it controls.[45] The Islamic State invests the most resources in strategically important areas where it believes it can maintain control.

The Islamic State uses its extreme interpretations of takfir and Salafism to justify the group’s brutality. New recruits are quizzed in theology, but not all recruits join the group for religious reasons.[46] Sharia training is part of the organizations indoctrination process, and those that question the brutality of the group are re-educated in the specific interpretations the group has derived from religion and history.[47] More senior members of the organization focus on strategic works from militant Islam including Abu Bakr Naji’sManagement of Savagery. Naji viewed politics as essential to the militant movement, and stressed the need to communicate Sharia-based justifications through propaganda. He wrote that this was the means through which a movement could build a state.[48]

The Islamic State stresses particularly “arcane” episodes from the earliest days of Islam, often using obscure punishments that are then broadcast by its extensive propaganda machine.[49] Hassan Hassan has noted that if a Salafist were to seek out explanations for such brutality, supporters of the Islamic State would be more willing to discuss the underlying logic and the particular episodes the group is seeking to emulate. In a way, the Islamic State projects its shared ideological history on all militant Salafists with the most brutal version of the movement. It dares these militants to accept the logic of the so-called Caliphate, which would necessitate joining the movement. While graphic punishments are a means of terrifying the population into obeying the Caliphate, they also serve as a propaganda message to Salafists around the world, demonstrating that the punishments and the system of governance from the first generation of Islam are once again in place.[50]

Abu Khalid al-Suri, who was likely assassinated in early 2014 by the Islamic State, is one example of so-called Afghan Arabs, militants who participated in the anti-Soviet conflict, operating in Syria.[51] The older generation of militants making their way to Syria may have presented the Islamic State with a challenge to their vision of exclusive political authority. The Islamic State also recently released an issue of Dabiq, its occasional online magazine, which accused Al Qaeda of deviating from Salafism with its embrace of Deobandi Islam and the Taliban. The article, with the title “Al Qaeda of Waziristan,” was written by an apparent former member of Al Qaeda, accused fighters in Asia of practices that would seem questionable to some militant Salafists. The publication also accused Al Qaeda of sending adherents to Syria in order to assert control over the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra. In this issue ofDabiq, the sixth edition from the terrorist group, bin Laden’s hesitation to declare Muslim leaders apostates is also referenced.[52] Interestingly, in this issue of Dabiq it is Zarqawi who convinces bin Laden to declare the rulers of Saudi Arabia and their armies to be apostates. In some versions of this story, it was Abu Musab al-Suri who advocated declaring the Saudi royal family apostates a decade before this alleged discussion.[53] The former Al Qaeda militant also includes the rulers of Muslim autocracies and their entire armies to be apostates. This is an expansive version of takfir including potentially hundreds of thousands of Muslims as targets for excommunication and death, something Al Qaeda has always sought to avoid but the Islamic State seems willing to attempt.

The Situation as it Stands

While the Islamic State has increasingly been attacked by Western and regional powers, it is unlikely that the Sunni insurgencies in both Syria and Iraq will end peacefully in the near future. Another version of the Sunni Awakening is unlikely while Iraqi politics remain sectarian and polarized, and while Iraqi Security Forces operate alongside Shia militias as they have done in 2014 and 2015.[54] The newest Interior Minister in Iraq is a member of the Badr Organization, a group led by Hadi Al-Amiri. Amiri is a former death squad commander who had a fondness for drilling Sunni skulls. Badr had sought to place Amiri in this important security post, but settled on a compromise.[55] It is doubtful that this compromise will engender much optimism from the Sunni community. The Islamic State represents a joining of the Syrian and Iraqi conflict among Sunnis and at the same time this has occurred among Shia militants. Shia militants from Syria have traveled to fight the Islamic State and other Sunni factions in Iraq.[56] Iran has been deeply involved in supporting Shia militias as has Lebanese Hezbollah. The Islamic State’s broad interpretation of takfir and their willingness to kill innocent Shia encourages extremism among the Shia communities of Iraq and Syria. A vicious cycle of sectarian violence appears to be prevailing in the region.

Salafism has appealed to opposition groups across a broad stretch of the Islamic world. In the North Caucasus much like in Syria, Salafism emerged as a unifying force even though it had little previous influence in the region. In that region of the world, local Islamic authorities were also seen as corrupt and beholden to the regime, with Salafism offering a sociopolitical order and a unifying ideology to replace those in power. Also as in Syria, repression from the ruling elites and an influx of Salafist-terrorists hardened the rebellion into one with extremist religious overtones.[57] Now, fighters from the North Caucasus as well as Afghanistan and Pakistan have joined their Arab coreligionists to fight the autocrats of the Middle East.

Despite Salafism’s apparent simple sociopolitical program, there have been three main interpretation within the Salafists movement: Quietist, Democratic, and Militant. Quietists have focused on preparing society for a return to an idealized form of governance. The democratic-Salafists, sought to gain power through elections. With the fall of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, this segment of the movement has hit a significant setback. However, the involvement with elections indicates that innovation within Salafism can occur. More ominously, however, militant Salafists are also innovating new methods of state-building as well as broader definitions of excommunication. Understanding the ideology behind these movements is critical to addressing potential challenges to peace and stability. It should also be noted that Salafist militancy seems to be more radicalized, especially with Iran gaining greater influence in the Middle East. As Quintan Wiktorowicz has observed, there has been an “erosion of critical restraints used to limit warfare and violence in classical Islam” that helped Islam to reach its highest cultural contributions.[58] The militant factions within the movement have attempted state-building and this is likely to continue. Prominent thinkers in this movement have studied successful insurgencies from around the world as well.[59] The autocrats of the Middle East now face a significant challenge against the legitimacy and integrity of their states. There is a danger that the militant faction of Salafism will improve upon state-building and create further challenges for us all.

Chris Zeitz is a veteran of military intelligence within the U.S. Army who served one year in Afghanistan. While in the Army, he also attended the Defense Language School in Monterey and studied Modern Standard Arabic. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Diplomacy from Norwich University. The opinions expressed are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Waagemakers, J. (2015, January 27). “Jihadi — Salafi Views of the Islamic State,” Monkey Cage Blog of the Washington Post, Accessed from:http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2015/01/27/jihadi-salafi-views-of-the-islamic-state/

[2] Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). “A Genealogy of Radical Islam,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 28, p. 77.

[3] Wiktorowicz, p. 78–80.

[4] Wiktorowicz,, p. 81

[5] Wiktorowicz,, p. 83

[6] Wiktorowicz, p. 78; Roy, O. (1990). Islam and Resistance in Afghanistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 56–67

[7] Wiktorowicz,, p. 76

[8] Wiktorowicz,, p. 83–84

[9] Wiktorowicz,, p. 89

[10] Wright, L. (2006, September 11). “The Master Plan: For the New Theorists of Jihad, Al Qaeda Is Just the Beginning,” The New Yorker, Accessed from:http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/09/11/the-master-plan

[11] Wagemakers, J.

[12] Wagemakers, J.

[13] Zelin, A. (2014). “The War between ISIS and al-Qaeda for Supremacy of the Global Jihadist Movement,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, p. 2–3 Accessed from: http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-war-between-isis-and-al-qaeda-for-supremacy-of-the-global-jihadist; Wright

[14] Zelin, p. 2

[15] Wright

[16] Cruickshank, P. & Hage Ali, M. (2007). “Abu Musab Al Suri: Architect of the New Al Qaeda,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 30, p. 2

[17] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. (2014) “The Group that Calls Itself a State: Under-standing the Evolution and Challenges of the Islamic State, Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, p. 3 Accessed from:https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-group-that-calls-itself-a-state-understanding-the-evolution-and-challenges-of-the-islamic-state

[18] Cruickshank & Hage Ali, p. 3

[19] Cruickshank & Hage Ali, p. 4

[20] Lister, C. (2014), “Profiling the Islamic State,” Brookings Doha Center Analysis Paper, p. 6 Accessed from:http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports2/2014/12/profiling-islamic-state-lister

[21] Cruickshank & Hage Ali, p. 7

[22] Cruickshank & Hage Ali, p. 9–11

[23] Chulov, M. (2014, December 11). “ISIS: The Inside Story,” The Guardian, Accessed from:http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/11/-sp-isis-the-inside-storyon February 9, 2015.

[24] Chulov

[25] Chulov

[26] Chulov

[27] International Crisis Group. (2012, October 12), “Tentative Jihad: Syria’s Fundamentalist Opposition,” Middle East Report No. 131, p. 4. Accessed from: http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/media-releases/2012/mena/syria-tentative-jihad-syria-s-fundamentalist-opposition.aspx; Schanzer, J. & Tahiroglu, M. (2014). “Bordering on Terrorism: Turkey’s Syria Policy and the Rise of the Islamic State,” p. 8–9 Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Accessed from:http://defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/schanzer-jonathan-bordering-on-terrorism

[28] ICG p. 1–7

[29] ICG, p. 11–13

[30] Caris, C. & Reynolds, S. (2014). “ISIS Governance in Syria,” Middle East Security Report No. 22, Institute for the Study of War, p. 10 Accessed from:http://www.understandingwar.org/report/isis-governance-syria

[31] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 16; Lister, p. 13

[32] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 21; Lister, p. 13–14

[33] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 24–25

[34] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 17

[35] Lund, A. (2014, February 24) “Who and What Was Abu Khalid al-Suri Part I,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Accessed from:http://carnegieendowment.org/2014/02/24/who-and-what-was-abu-khalid-al-suri-part-i

[36] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 22–71

[37] Morris, L. (2014, October 18). “Appointment of Iraq’s New Interior Minister Opens Door to Militia and Iranian Influence,” Washington Post, Accessed from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/appointment-of-iraqs-new-interior-minister-opens-door-to-militia-and-iranian-influence/2014/10/18/f6f2a347-d38c-4743-902a-254a169ca274_story.html

[38] Visser, R. (2014). “Iraq’s New Government and the Question of Sunni Inclusion,” CTC Sentinel, 7 (9), p. 14–16.

[39] Adnan, S. & Reese, A. (2014). “Beyond the Islamic Insurgency: Iraq’s Sunni Insurgency,” Middle East Security Report No. 24, Institute for the Study of War, p. 4, 10–13 Accessed from:http://www.understandingwar.org/report/beyond-islamic-state-iraqs-sunni-insurgency

[40] Adnan, S. & Reese, A. p. 16–17

[41] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 23

[42] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 19

[43] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 43

[44] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 65–67

[45] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 75

[46] Hassan, H. (2015, January 24). “The Secret World of ISIS Training Camps — Ruled by Sacred Texts and the Sword,” The Guardian, Accessed from: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/25/inside-isis-training-camps

[47] Hassan, H

[48] Wright, L. (2006, September 11). “The Master Plan: For the New Theorists of Jihad, Al Qaeda Is Just the Beginning,” The New Yorker, Accessed from: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/09/11/the-master-plan

[49] Hassan, H

[50] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B. p. 70

[51] Lund, A. (2014, February 25) “Who and What Was Abu Khalid al-Suri Part II,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Accessed from:http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=54634

[52] Joscelyn, T. (2015, January 5). “The Islamic State’s Curious Cover Story,” Long War Journal, Accessed from:http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/01/al_qaeda_defector_fe.php

[53] Cruickshank, P. & Hage Ali, M. p. 2

[54] al-‘Ubaiydi, M., Lahoud, N., Milton, D. & Price, B., p. 79

[55] Morris, L. (2014, October 18). “Appointment of Iraq’s New Interior Minister Opens Door to Militia and Iranian Influence,” Washington Post, Accessed from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/appointment-of-iraqs-new-interior-minister-opens-door-to-militia-and-iranian-influence/2014/10/18/f6f2a347-d38c-4743-902a-254a169ca274_story.html

[56] Smyth, P. (2015). “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and Its Regional Effects,” Policy Focus 138, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, p. 2 Accessed from: http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-shiite-jihad-in-syria-and-its-regional-effects

[57] Souleimanov, E. (2011). “The Caucasus Emirate: Genealogy of an Islamist Insurgency,” Middle East Policy, 18 (4), p. 159–162

[58] Wiktorowicz,, p. 94

[59] Ryan, M. (2013, September 22). “What Al Qaeda Learned from Mao,” The Boston Globe, Accessed from:http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/09/21/what-qaeda-learned-from-mao/E7Ga91ZVktjgiyWC90nJ6M/story.html

#Reviewing ISIL's Playbook

A Look at Managing Savagery:

The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Uma will Pass

ISIL has a textbook. Its actions thus far have so closely followed this textbook, it is astounding. The textbook is translated into English, and not particularly difficult to read and understand. Suspend your disbelief. Maybe ISIL is more than a random group of irreverent murderous thugs taking advantage of ungoverned space. Maybe the counter-ISIL strategy is lacking.

Managing Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Uma Will Pass was written by Islamic strategist Abu Bakr Naji in 2004, translated in 2006 by William McCants who is a leading scholar of militant Islam. It describes a three phase approach to establishing an Islamic state. The theory behind ISIL’s entrenchment in Iraq and Syria is accurately described in the decisive operation, managing savagery. But don’t be misled by the terminology. “Savage” refers to non-Muslims and moderate Muslims. The violence ISIL displays is an effort to “manage” the “savages.” It is a disciplined program to establish Salafism, and its members are not undisciplined criminals any more than the Nazi Gestapo in the 1930s, or Stalin’s security apparatchiks in the 1950s.

The book is highly prescriptive, more Jominian than Clauswitzian, and equally brilliant. The author describes a version of mission command under the heading “art of management” providing guidance for who should lead, how to make decisions, how to delegate authorities, when to engage in combat, when to use violence against a population, Sharia law and justice, and how to gain and maintain the initiative. He describes formidable obstacles to establishing an Islamic state and what to do about them, such as: countering infiltration of adversaries, countering Western messaging, increasing the lack of administrative cadres, how to minimize members changing loyalties, and how to reverse the decreasing numbers of “true believers.”

The three phased approach bears striking similarity to US operational doctrine, which begins with shaping operations, then decisive combat operations, and then transition to peace.

It is not a coincidence that Americans now characterize themselves as “war weary,” because they are victims of a deliberate strategy of exhaustion.

The first phase, according to the author, is “vexation and exhaustion.” It can be compared to the colonial American Continental Army’s approach to combat against the British Empire in the 1700s, or any number of successful asymmetric conflicts throughout the centuries. In such cases, the weaker opponent must wear down the stronger opponent until it can achieve some level of parity. The author provides a number of historic examples, all of which seem to pit Islamic warriors against non-believers. The most compelling is the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, where the Mujahedeen successfully wore down the Red Army. The book describes setting strategic “traps” for Americans in Iraq, causing the US to plunge further and further into an inescapable quagmire. It is not a coincidence that Americans now characterize themselves as “war weary,” because they are victims of a deliberate strategy of exhaustion.

This strategy is in fact an extension of Usama Bin Laden’s strategy of limited warfare employed by Al Qaeda. Abu Bakr Naji assumed that pulling Americans deeper into the Iraq war would eventually lead to the collapse of the United States because he inaccurately attributed the collapse of the Soviet Union to Mujahedeen operations in Afghanistan. Therefore, its strategy of exhaustion against the US was only partially successful. Although it succeeded in making Americans war weary, it has yet to achieve its desired goal, which is the collapse of the United States.

The second phase of establishing an Islamic state, “managing savagery,” is the decisive operation and best describes current ISIL efforts. The focus of the second phase is to remove elements it believes as cancerous to a pure Islamic society. Although Western media sources tend to characterize ISIL’s penchant for dramatic executions as irrational, the source of its violent behavior is rational because it follows a logical purpose motivated by a combination of fear, honor, and interest. Although brutal and abhorrent, it is rational in the same sense that the Rwanda Genocide in 1994, or Nazi extermination of Jews, followed a logic and purpose. Garnering very little attention in Western media, ISIL also forces the population to continue working; requiring bakeries and administrative offices to remain open. It patrols the streets to ensure markets and retail stores are not mobbed or looted. It appoints local villagers as leaders. It establishes a school system to “properly educate” the next generation of Salafi Muslims. It establishes courts and a system of justice, beginning with a public square in which public executions may be conducted. Compared to Nouri Al Maliki’s Iraq, or Bashir Al Asad’s Syria, much of the Sunni population find ISIL governance more attractive.[1]

The third phase focuses on expanding the Islamic state and provides guidance on establishing affiliations, franchises, and alliances. The book even explains which countries and regions are ripe for an Islamic revolution. Particularly noteworthy, the author rejects the boundaries of existing Middle Eastern countries as western colonial fabrications. When he refers to “Syria” for example, he is referring to a population that likely spans into Turkey and Iraq. His theory of expansion seems to be theoretically similar to the Marxist expansion of communism, in the sense that a global revolution establishing a pure Salafi Islamic state is inevitable.

Overall, the strategy described in Managing Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Uma will Pass is a brilliant and artful theory of achieving a very difficult end state with extremely limited means. Since it is the strategy of our adversary, this conclusion may be difficult to accept. Even more difficult to accept is the necessity to re-think the counter-ISIL strategy in the context of ISIL’s text book. Specifically, will the counter-ISIL strategy destroy ISIL, or feed into the establishment of an Islamic state? If the strategy is similar to Communist expansion, would a closer study of George Kennan’s containment strategy outlined in his “Long Telegram” be more appropriate? In a region where Western democracy is not understood and largely rejected, what alternatives to Assad and Maliki can the U.S. provide that ISIL is not providing?

Harry York is a strategic planner in the Pentagon. He holds a Master’s Degree from the Army School of Advanced Military Studies and a Bachelor’s Degree in Russian from the University of Washington. He has multiple deployments to both Iraq and Afghanistan as both an aviator and an operational planner. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[i] Mr. Hassan Hassan, co-author of the best selling book ISIS: The Army of Terror and whose home town is in ISIL held Syria, stated in a Pentagon lecture on 11 March 2015, “Some people like that ISIL establishes law and order. Sunni populations do not want Shia militias operating on their soil, even to “free” them from ISIL. Therefore, ISIL is gaining support despite military defeats. It is strategically winning in part because there is no sustainable governance replacing it, and moderates are becoming weaker. In addition, no one says what will replace ISIL. Some say ISIL is crumbling (referencing a Washington Post Article by Liz Sly), but it is not.

When It's Personal #Profession

I teach an undergraduate course on International Relations at an online university popular with military students. During one of my classes, two of the students, one a former Reconnaissance Marine and the other an Army Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) technician, had a lengthy discussion about their frustration with US foreign policy. Both of these students had spent a considerable amount of time in Iraq, both in forward combat positions. The EOD technician was especially upset with the rise of the “Islamic State” in Iraq over the past year. I routinely encourage my students to talk about their military experiences, which they do. Most of the time they share some interesting perspectives, but this student truly caught my attention when he discussed his perceptions of Iraq. He said, “the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.”

…the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.

In response, the Marine student replied, “I separated myself very quickly from our actions and their success…They were given the tools to make it happen and it is up to them. Ultimately I do not care if the cities and nations I fought in crumble to the ground, as it is not my responsibility to keep them safe. My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.”

My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.

While the EOD technician feels deeply frustrated about US foreign policy for personal reasons, namely the loss of life, the Marine has been able to distance himself from recent events. For him, the mission ended when he left Iraq, and he feels nothing personal about the situation taking place on the ground now.

The dialogue between these two young men resonated with me quite deeply. I think their conversation precisely reflects two distinct ways of assessing a wartime experience: one professionally and one personally. Much like them, I have often questioned my own interest in our foreign policy in Iraq: is it professional or is it personal? I spent time in Baghdad during the surge and witnessed hundreds of reconstruction, reconciliation, and good-will projects in the country. I have quite a few professional contacts that are either Iraqi or have worked in Iraq. My PhD course work focuses on Iraqi politics, and I have a serious academic interest in the history of the country. Yet, as an academic, I have a duty to remain objective and impartial in my analysis of the political situation.

Despite this professional stance, I do feel personally responsible for mistakes our government has made. When I saw how swiftly the Islamic State took Mosul and sections of Anbar province last year, I was not only horrified and disgusted, but I also felt disillusioned, and I felt like my very own mission in the country had failed. Not only that, I was profoundly disturbed with how we treated Iraqis that came to the aid of the U.S. military during the surge. For instance, without the Sons of Iraq, the momentum from the surge probably would not have turned the tide on Al Qaeda so quickly. Yet, we abandoned our moral obligation to help these young men, and instead used them for political collateral. After six years, it is very hard for me, as an American, to look these people in the eye. Perhaps its the lurid and visceral nature of war that distinguishes it from most professions, and those situations can feel so deeply personal.

So, did my personal responsibility for the situation end when I left Iraq? For me, it did not. Although, I do think that for most people this is a very good way of coping with their wartime experiences. If I happened to be in a different profession, then yes, perhaps I would have the same mentality as my Marine student. For instance, if I was an active duty serviceman, I would likely distance myself, mentally, from the events that took place in Iraq, especially the ones that were beyond my control. Personal feelings can cloud judgment and rational decision-making. It is difficult to remain objective, and having personal feelings can make it even more difficult to “move on” from a negative situation. When faced with negative situations in the workplace, it is best to keep it professional, and accept responsibility where responsibility is due. When the mission is over, put it to rest, because thinking about past events is highly unlikely to change them.

…I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in American foreign policy and decision-making.

Yet, despite this, I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in US foreign policy and decision-making. I believe this is the responsibility I bear as an American that was involved in the conflict. And, while it is a tragedy, I also see it as a chance to learn. I think most people going to be split on how to approach this subject, and I would be very curious as to what others think about it. My own thought is that the true professional must constantly balance their obligations to their employer or service against their personal experience, knowing that a certain amount of empathy and ownership is required in order to process wartime events in a way that is both humane and just.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. This post was inspired by Tyrell Mayfield who, speaking on his own experiences in Afghanistan stated, “I’m personally vested, which is different than a professional obligation.”

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

A Time to Leave

You missed your chance to go to war, so now what?

A young captain was considering his options. As a lieutenant he deployed in support of a relatively small campaign at the time, and did not see much action. Soon after his nation launched a much larger campaign in another country that instantly became the United States’ main effort. His West Point classmates were jockeying for positions on the front lines and staffs of the various commands so as not to miss the big moment. Dutifully he sought a position where he hoped to prove himself in the crucible of war. The gods of war had other plans for the young officer, as he found himself relegated to a backwater post performing administrative duties in support of the war, but far away from the action. Now a captain, he pitted his career in the army to date against the offers of employment and advancement in the civilian world and found the army came up short. He decided to leave.