If you are looking for an accessible, practical introduction to moral psychology and ethics for undergraduate, Professional Military Education classes, or the general interest reader, look no further. Philosopher and psychology researcher Christian Miller’s The Character Gap distills much of his own scholarly work, as well as the thoughts and writing of others, into a readable, accessible volume with practical examples, citations from important studies, and popular culture references that bring alive questions of moral character and development. This volume asks us not just to consider others’ moral character, but also reflect upon our own, the gaps in it, and how we can improve it.

#Reviewing How to Think Like an Officer

The ideas that Bonadonna espouses for improving officer education and for widening the lenses that get used to examine problems have much to commend them. His arguments that there are elements of military culture that need to be re-examined and changed will certainly raise questions, but this is a good thing…Investing in the time to examine how officers think, and considering how we can improve upon the status quo, is an investment worth making. Arguably, doing so is a requirement of anyone belonging to the military profession.

#Reviewing The Rise and Fall of an Officer Corps

With Taipei’s economic and diplomatic fortunes having gone south (vis-à-vis Beijing’s) in recent decades—coupled with the rising stature of the Chinese armed forces—the story of the original party-army that ruled China proper, indubitably, has been neglected by both popular media and academe alike. In this present context, The Rise and Fall of An Officer Corps is a timely contribution to our understanding of modern China and its military history.

Military Politics in an Age of Transition: #Reviewing A British Profession of Arms

Why, one might ask, is the late Victorian British army of any relevance to the U.S. military in 2019? Simply put, many of the ideas and themes discussed by Beckett are of timeless interest to those concerned with the ways in which professions ought to, and actually do, function. In fact, there are a striking number of analogies between the British Empire during the late Victorian and Edwardian period and the current geopolitical situation of the United States.

From Screen to Paper: Redefining the Modern Military

The professionalism of Western militaries is ripe for another discussion. The practitioners who make up the profession of arms—and those that study and teach them—owe it to their citizens, their governments, and themselves to shape their forces, and educate their professionals, in preparation for the future. It is their duty to ensure they are prepared to ethically and effectively achieve the military objectives their leaders lay before them, no matter the adversary or the context of the conflict.

Improving Advice and Earning Autonomy: Building Trust in the Strategic Dialogue

Good military advice flows out of trust relationships, and the candor that good military advice requires depends on mutual trust. Yet Huntington’s theory has created the lasting impression that civilian leaders must implicitly trust, and grant autonomy to, military leaders. Autonomy is not—and should not be—mechanistically or automatically granted; like trust, autonomy must be earned and re-earned continuously through the daily demonstration of character and competence, and the commitment by members of the profession to police themselves and hold one another accountable. So, after more than sixteen years of inconclusive wars, it is time for military officers to step out of Huntington’s shadow and improve the quality and nature of the military advice they provide.

Beyond the Band of Brothers: Henry V, Moral Agency, and Obedience

What level of moral agency, judgment, and responsibility do individual members of the military bear in war? In 2006 Lt Ehren Wahtada tried to selectively conscientiously object to deploying to Iraq, while in 2013 service members appeared on social media to proclaim they would not fight in a war in Syria[1] . These are only two examples that illustrate the way in which this debate is live and permeates military culture. On the academic side, Michael Walzer and Jeff McMahan (and their proxies) have been engaged in this debate for quite some time, pitting individualist accounts against the conventional view that soldiers are instruments of the State. I want to examine this debate and put forward an alternative view to those typically espoused, expanding and advancing the ethical discussion in the process.

#Leadership and the Art of Restraint

Major General Cantwell’s words articulate the frustration of having to justify actions at the tactical level to those far removed from the area of operations. There are certainly important reasons for having to do this, such as the need to update higher levels of command with the progress of operations, and to explain why certain incidents have occurred. Indeed, accountability for decisions made and actions taken is an enduring feature of civil-military relations in democratic nations.

When It's Personal #Profession

I teach an undergraduate course on International Relations at an online university popular with military students. During one of my classes, two of the students, one a former Reconnaissance Marine and the other an Army Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) technician, had a lengthy discussion about their frustration with US foreign policy. Both of these students had spent a considerable amount of time in Iraq, both in forward combat positions. The EOD technician was especially upset with the rise of the “Islamic State” in Iraq over the past year. I routinely encourage my students to talk about their military experiences, which they do. Most of the time they share some interesting perspectives, but this student truly caught my attention when he discussed his perceptions of Iraq. He said, “the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.”

…the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.

In response, the Marine student replied, “I separated myself very quickly from our actions and their success…They were given the tools to make it happen and it is up to them. Ultimately I do not care if the cities and nations I fought in crumble to the ground, as it is not my responsibility to keep them safe. My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.”

My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.

While the EOD technician feels deeply frustrated about US foreign policy for personal reasons, namely the loss of life, the Marine has been able to distance himself from recent events. For him, the mission ended when he left Iraq, and he feels nothing personal about the situation taking place on the ground now.

The dialogue between these two young men resonated with me quite deeply. I think their conversation precisely reflects two distinct ways of assessing a wartime experience: one professionally and one personally. Much like them, I have often questioned my own interest in our foreign policy in Iraq: is it professional or is it personal? I spent time in Baghdad during the surge and witnessed hundreds of reconstruction, reconciliation, and good-will projects in the country. I have quite a few professional contacts that are either Iraqi or have worked in Iraq. My PhD course work focuses on Iraqi politics, and I have a serious academic interest in the history of the country. Yet, as an academic, I have a duty to remain objective and impartial in my analysis of the political situation.

Despite this professional stance, I do feel personally responsible for mistakes our government has made. When I saw how swiftly the Islamic State took Mosul and sections of Anbar province last year, I was not only horrified and disgusted, but I also felt disillusioned, and I felt like my very own mission in the country had failed. Not only that, I was profoundly disturbed with how we treated Iraqis that came to the aid of the U.S. military during the surge. For instance, without the Sons of Iraq, the momentum from the surge probably would not have turned the tide on Al Qaeda so quickly. Yet, we abandoned our moral obligation to help these young men, and instead used them for political collateral. After six years, it is very hard for me, as an American, to look these people in the eye. Perhaps its the lurid and visceral nature of war that distinguishes it from most professions, and those situations can feel so deeply personal.

So, did my personal responsibility for the situation end when I left Iraq? For me, it did not. Although, I do think that for most people this is a very good way of coping with their wartime experiences. If I happened to be in a different profession, then yes, perhaps I would have the same mentality as my Marine student. For instance, if I was an active duty serviceman, I would likely distance myself, mentally, from the events that took place in Iraq, especially the ones that were beyond my control. Personal feelings can cloud judgment and rational decision-making. It is difficult to remain objective, and having personal feelings can make it even more difficult to “move on” from a negative situation. When faced with negative situations in the workplace, it is best to keep it professional, and accept responsibility where responsibility is due. When the mission is over, put it to rest, because thinking about past events is highly unlikely to change them.

…I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in American foreign policy and decision-making.

Yet, despite this, I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in US foreign policy and decision-making. I believe this is the responsibility I bear as an American that was involved in the conflict. And, while it is a tragedy, I also see it as a chance to learn. I think most people going to be split on how to approach this subject, and I would be very curious as to what others think about it. My own thought is that the true professional must constantly balance their obligations to their employer or service against their personal experience, knowing that a certain amount of empathy and ownership is required in order to process wartime events in a way that is both humane and just.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. This post was inspired by Tyrell Mayfield who, speaking on his own experiences in Afghanistan stated, “I’m personally vested, which is different than a professional obligation.”

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

A Time to Leave

You missed your chance to go to war, so now what?

A young captain was considering his options. As a lieutenant he deployed in support of a relatively small campaign at the time, and did not see much action. Soon after his nation launched a much larger campaign in another country that instantly became the United States’ main effort. His West Point classmates were jockeying for positions on the front lines and staffs of the various commands so as not to miss the big moment. Dutifully he sought a position where he hoped to prove himself in the crucible of war. The gods of war had other plans for the young officer, as he found himself relegated to a backwater post performing administrative duties in support of the war, but far away from the action. Now a captain, he pitted his career in the army to date against the offers of employment and advancement in the civilian world and found the army came up short. He decided to leave.

Another young captain had spent months training and preparing himself and his unit for combat, but the big day never came. He graduated from West Point with plenty of time to deploy overseas and lead soldiers in battle. But it seemed that every time he thought he was about to go, the deployment shifted to the right. The last time, major combat operations ended and his unit fell off the patch chart entirely. It was wholly counter intuitive that a soldier who was willing and eager to go to war would be denied the chance and it ate him up inside. He faced a shrinking force, slashed budgets, and a nation eager to forget the trials of war and bring the nation back to a peacetime mentality, shirking any further overseas adventurism. The captain had a decision to make.

The third and final young officer had spent his time at the academy as the war was winding down. He often considered his future service, and the rising discontent with the government’s handling of the situation. Upon his commission, the war was over for America but he still resolved to give the army his best effort. This in the face of incredible adversity, as a generation of combat leaders dominated the ranks and the force struggled to transform itself despite opposition from both the inside and outside. The army was coming off what many believed to be an unequivocal loss and morale was incredibly low as the best and brightest left for greener pastures or burnt out early and left holding feelings of bitter resentment. His uneventful lieutenant years led to uneventful captain years as he moved from one type of unit to the next. Throughout it all, this captain remained determined to excel, though why sometimes seemed a mystery.

These young officers have much in common. The early parts of their careers saw bitter disappointment as the wars in which their nation was engaged drew to a close, with none of them having taken part. They entered a force faced with budget cuts, sagging morale, questionable civilian support, and in desperate need of transformative change. No doubt each in his own way looked the uncertain future with trepidation and apprehension. Each in his own way navigated through years of boredom and frustration all the while consciously or unconsciously having experiences that shaped and molded them. What none of them could have known, especially as they navigated through their early years was that eventually they would be called upon to guide the military and serve as a rallying point for the nation through periods of extraordinary crisis and uncertainty.

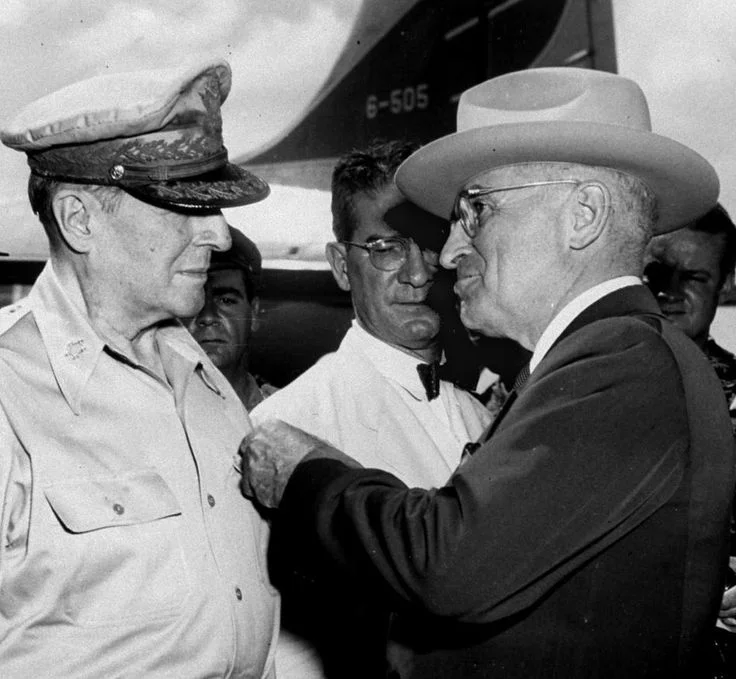

“General William Tecumseh Sherman, 1865” by Mathew Brady (1823–1896) — recolored by COLORIZEDHISTORY // Harry Warnecke’s victory portrait of Dwight Eisenhower, right after the end of World War II. © 2012 Daily News, LP. // “GEN Petraeus Aug 2011 Photo” by Monica A. King; DoD photographer — US Military.

The careers of William Tecumseh Sherman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and David H. Petraeus were forged in the fires of wars that were unimaginable to many of their generations, and for posterity. Yet none of them reached the pinnacle of their (military) success until late in their careers, well beyond the average wear out date for officers with no combat experience hailing from a what had been a peacetime army. Fortunately, we will never know what would have happened if Petraeus had let his ambition wane, if Eisenhower had let his resentment overcome him, or if Sherman had decided to remain a private citizen. Similarly no officer who has commissioned in the last few years will know what they can become if they decide to quit simply because they feel their glory years have already passed them by.

No doubt many recently commissioned officers and recently enlisted soldiers wonder what the future holds for them. A new entry into the military today was somewhere between preschool and elementary when the events of 9/11 happened — the memory of that day is fading with each passing generation. The face(s) of Al-Qaeda have been captured, killed, or driven underground with their ruin being spread across information outlets worldwide to make them seem akin to the boogie man. America has fought long, bloody wars in strange lands, withdrawn, and shown little appetite for further adventurism, even in the face of heinous acts of brutality and blatant aggression by new enemies. Domestically the political process seems broke as the legislative and executive branches attempt to score cheap political points off one another. All the while pundits, politicians, and private citizens have lamented the handling of the conflicts, the lack of strategy, and have decried America’s supposedly waning influence.

To men like William Tecumseh Sherman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and David H. Petraeus this all must be familiar. Each grew up and came to thrive in similar climates of adversity and discontent. Perhaps if each had been told when they were a junior officer that one day they would lead armies and have a nation depend on them they would have scoffed in disbelief, dismissing it as the application of hot air to an under-inflated ego. Regardless, each continued to contribute to the profession of arms as best they could under the circumstances (even Sherman, who did leave the service, but was never far or long from it). They drove themselves to excel academically and professionally, they found mentors, they read and wrote, and they studied and later championed methods of warfare previously ignored or disparaged by the regular army. When given the reins each saw their wars for what they were, and tailored their approaches to achieve victory.

But first they made the decision to serve when all the chips seemed down and the deck stacked against them. They were not omniscient, they could not have foreseen the role they would each play — even then they could have rejected that role and let slip the baton to more willing hands. Yet they persevered, and did not quit on the army even when the army seemed to quit on them.

Young leaders today who feel they have missed the big game, or did not get their fair share of playing time should consider carefully what they would be leaving behind. Each of the services are embarking on exciting periods of evolution, as they try to define their places in the future and develop new doctrines and innovative techniques to match. And rest assured, there will be another chance — there will be a time when America sends her sons and daughters into battle again. America is still preeminent, and its obstacles are many and its enemies implacable. Who is going to lead into the next century? Who are you going to emulate — who is the next Sherman, Eisenhower, or Petraeaus? Maybe it’s you.

Don’t quit and find out.

Nathan Wike is an officer in the U.S. Army, and an associate member of the Military Writer’s Guild. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Which Way Lies Salvation?

A Discussion on Dishonesty in the Military Profession

Recently two U.S. Army War College professors published an incisive, well-researched study entitled “Lying to Ourselves: Dishonesty in the Army Profession.” The title instantly conjures images of an Army immersed in sin, where a soldier cannot be trusted to speak the truth. The study itself generated attention grabbing headlines from widely read publications such as the Washington Post, CNN, as well as Army Times, which bemoaned the corruption of the Army officer corps, on which the study is based. This in turn led to a flurry of internet activity as currently serving and retired service members of all branches and ranks (all having read the study no doubt) lined up to comment on the depravity of the Army’s officers, the Army in general, and that the study’s conclusions should surprise no one. Largely absent have been calls for moderation or an official statement regarding the conclusions drawn by the authors. For a formal study by one of the military’s premiere institutions, the lack of a response is perhaps the most alarming reaction of all.

Foremost it is necessary to point out that this is a study meant for the consideration of the entire military. As stated by the authors:

While the phenomenon we are addressing afflicts the entire U.S. military, we focus on the U.S. Army because it is the institution with which we are most familiar (as professors at the [U.S. Army War College]). While the military profession can be broadly conceptualized to include anyone who serves in the Department of Defense (DoD), we give particular attention to the experiences of the Army officer corps. The officer corps is a bellwether for the military. [1]

This study is not an indictment of the Army officer corps. It is a clarion call to the military and its overseers that a fundamental value of the service, honor, has eroded and change is needed for it to be revitalized.

In this study, the Army officer corps serves as a focus group for the entire Department of Defense — though several U.S. Marine Corps officers were also interviewed for the study, as mentioned on page six. The authors acknowledge on page one that the study comes at time when ethical failings are occurring across the uniformed military, throughout the ranks of both officer and enlisted. This study is not an indictment of the Army officer corps. It is a clarion call to the military and its overseers that a fundamental value of the service, honor, has eroded and change is needed for it to be revitalized.

If you have ever sat through a block of mandatory training or death by power point style briefs, filled out a story board, signed a unit finance report, wrote and evaluation, sat through a training meeting or command and staff, assessed the end of a campaign for your superiors, etc. this study will resonate. While you may not be guilty of any sort of dishonesty per se, certainly you can see where it is possible or even likely for others to get lost in the deluge of requirements and expectations. Furthermore, you must appreciate the immense pressure to report information that keeps with higher headquarter’s expectations. It maybe that you have seen the consequences of someone reporting the “wrong” but correct information and found them unfair but not unexpected. Considering all that, you can perhaps understand,though not condone, a soldier, sailor, airman, marine, non-commissioned officer, or officer’s propensity to “pencil whip,” “hand wave,” or “fudge” the numbers.

So the phrase “…officers (leaders), after repeated exposure to the overwhelming demands and the associated need to put their honor on the line to verify compliance, have become ethically numb” (Gerras and Wong 2015, ix) among all the quotable passages, hits like a thunderbolt. It should cause a moment of reflection in anyone who reads it. Why are satirical news sources like The Duffel Blog, comic strips like Terminal Lance, or humorists like Doctrine Manso popular and their messages so poignant and relatable? Why are service members so eager to speak out on forums and blogs across the internet (sometimes with less than desired results) or to flock to organizations like theDefense Entrepreneurs Forum? Is the force ethically numb? Has a leader’s signature or their word become commodities to be traded for favor and advancement? Have I been part of the problem? How can this problem be fixed?

To claim there is no problem is to espouse willful ignorance and ignore the gathering storm.

Fair questions all, but the last two are the questions that should be getting asked throughout the Department of Defense. To claim there is no problem is to espouse willful ignorance and ignore the gathering storm. Drs. Gerras and Wong end their study with several recommendations and acknowledge at the beginning that even discussing the issue will be awkward and uncomfortable. Whose burden is most heavy for implementing the study’s recommendations, or finding other, better solutions? Clearly change needs to happen, but what direction will it come from — which way lies salvation, up or down?

“Brutus Falling on His Sword” imprint by Geoffrey Whitney, Emblema CXIX via A Choice of Emblems.(1586)

For the change to be driven from the bottom up, it requires the simple choice from a critical mass of leaders within the operational military who decide to be absolutely truthful on every report, evaluation, or requirement. A sudden drop in Unit Status Report numbers, a sharp rise in unfulfilled deployment requirements, or unexpected flat-line of promotion rates could not help but be noticed by the powers that be. The requirements will not go away overnight, so it would be necessary to consciously prioritize training tasks, disregard redundant requirements, and exhibit the personal courage to write a truthful evaluation supported by astute counselings. Such a trend would need to be sustained until it caused change. Those who implement this plan however would have to be prepared to answer some very tough questions, and suffer the consequences of being honest. In essence, a generation of junior leaders would have to refuse any distortion of the truth and possibly put their careers in jeopardy to keep their honor intact and revitalize the reputation of the military, as oxymoronic as it sounds.

For change to come from the top down first requires senior leaders to acknowledge the problem(s) and make fixing them a public priority. Next they must question and be skeptical of the information that is reported to them — if it seems too good to be true, it probably is. The culture of how information is received must change— rejecting information one wants to hear versus accepting information one needs to hear. The Department of Defense would have to initiate a review of its requirements to determine what is superfluous, outdated, or unnecessary for a military of the 21st Century and then change the doctrine and testify for changes to laws. This may directly affect the legacy, or even reason for existence of some senior individuals. In essence, senior leaders of today would have to make some tough decisions, and commit to addressing the issues and concerns throughout the force with scant regard for outside interests, institutional bias, or even hallowed traditions.

The problem is vast, but it is not insurmountable. Drs. Gerras and Wong’s study is not a shroud meant to cover the force in darkness. It is a beacon, like a lighthouse in a storm — one which we ignore at our peril. Though it maybe difficult to face, the issues identified compromise the fundamental values on which the military is built. Change can either be grassroots or in a stepwise fashion, driven from the bottom or the top, but change must come. It should not require a certain demographic to selflessly sacrifice themselves to bring honor back to the force when it never should have been abandoned. It is time for leaders of every rank, from every branch of service to aggressively lead the military to a more practical, honorable future and truly embody the values that are held so dear.

Nathan Wike is an officer in the U.S. Army, and an associate member of the Military Writer’s Guild. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Gerras, Stephen J, and Leonard Wong. Lying to Ourselves: Dishonesty in the Army Profession. Strategic Studies Institute, United States Army War College, Carlisle Barracks: U.S. Army War College Press, 2015.

#Professionals Know When to Break the Rules

The military is a profession. That does not mean that everyone in the military is a professional. There are many hard working service members grinding daily that do not meet that relatively high mark, but many others that do. So when does a soldier become a professional? In boot camp? On his first combat tour? Or in a classroom?Soldiers become professionals when they can make the right decision even when it contradicts the manual.

#Profession in One Tweet

Try the “One Tweet” challenge on your own. Capture what you perceive as the essential elements of your own profession or organization, and challenge your peers and subordinates to do the same. Keep in mind that challenges like this often reveal more in what they exclude than what they include. Compare the results and use the similarities and differences to drive a conversation that leads to actions like a “stop doing” list. You might be surprised by the results.

The Professional Bridge: Discourse and the Bondage of Needing the Right Answer

Truth can triumph over parochialism only when military professionals unburden themselves from responsibility for conclusive answers, which are ultimately monuments to obsolescence, and share their individual glimpses of reality to create an understanding of war that remains lacking in a still dangerous world.