The professionalism of Western militaries is ripe for another discussion. The practitioners who make up the profession of arms—and those that study and teach them—owe it to their citizens, their governments, and themselves to shape their forces, and educate their professionals, in preparation for the future. It is their duty to ensure they are prepared to ethically and effectively achieve the military objectives their leaders lay before them, no matter the adversary or the context of the conflict.

When It's Personal #Profession

I teach an undergraduate course on International Relations at an online university popular with military students. During one of my classes, two of the students, one a former Reconnaissance Marine and the other an Army Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) technician, had a lengthy discussion about their frustration with US foreign policy. Both of these students had spent a considerable amount of time in Iraq, both in forward combat positions. The EOD technician was especially upset with the rise of the “Islamic State” in Iraq over the past year. I routinely encourage my students to talk about their military experiences, which they do. Most of the time they share some interesting perspectives, but this student truly caught my attention when he discussed his perceptions of Iraq. He said, “the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.”

…the loss of life is exactly why I’m frustrated watching every city I spent time in crumble beneath the weight of ISIS. It is the most severe tragedy I have ever had to endure.

In response, the Marine student replied, “I separated myself very quickly from our actions and their success…They were given the tools to make it happen and it is up to them. Ultimately I do not care if the cities and nations I fought in crumble to the ground, as it is not my responsibility to keep them safe. My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.”

My responsibilities were tied to accomplishing the given mission and bringing back my Marines, that was it.

While the EOD technician feels deeply frustrated about US foreign policy for personal reasons, namely the loss of life, the Marine has been able to distance himself from recent events. For him, the mission ended when he left Iraq, and he feels nothing personal about the situation taking place on the ground now.

The dialogue between these two young men resonated with me quite deeply. I think their conversation precisely reflects two distinct ways of assessing a wartime experience: one professionally and one personally. Much like them, I have often questioned my own interest in our foreign policy in Iraq: is it professional or is it personal? I spent time in Baghdad during the surge and witnessed hundreds of reconstruction, reconciliation, and good-will projects in the country. I have quite a few professional contacts that are either Iraqi or have worked in Iraq. My PhD course work focuses on Iraqi politics, and I have a serious academic interest in the history of the country. Yet, as an academic, I have a duty to remain objective and impartial in my analysis of the political situation.

Despite this professional stance, I do feel personally responsible for mistakes our government has made. When I saw how swiftly the Islamic State took Mosul and sections of Anbar province last year, I was not only horrified and disgusted, but I also felt disillusioned, and I felt like my very own mission in the country had failed. Not only that, I was profoundly disturbed with how we treated Iraqis that came to the aid of the U.S. military during the surge. For instance, without the Sons of Iraq, the momentum from the surge probably would not have turned the tide on Al Qaeda so quickly. Yet, we abandoned our moral obligation to help these young men, and instead used them for political collateral. After six years, it is very hard for me, as an American, to look these people in the eye. Perhaps its the lurid and visceral nature of war that distinguishes it from most professions, and those situations can feel so deeply personal.

So, did my personal responsibility for the situation end when I left Iraq? For me, it did not. Although, I do think that for most people this is a very good way of coping with their wartime experiences. If I happened to be in a different profession, then yes, perhaps I would have the same mentality as my Marine student. For instance, if I was an active duty serviceman, I would likely distance myself, mentally, from the events that took place in Iraq, especially the ones that were beyond my control. Personal feelings can cloud judgment and rational decision-making. It is difficult to remain objective, and having personal feelings can make it even more difficult to “move on” from a negative situation. When faced with negative situations in the workplace, it is best to keep it professional, and accept responsibility where responsibility is due. When the mission is over, put it to rest, because thinking about past events is highly unlikely to change them.

…I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in American foreign policy and decision-making.

Yet, despite this, I’ve still made a conscious decision to take personal responsibility for what I see as a great failure in US foreign policy and decision-making. I believe this is the responsibility I bear as an American that was involved in the conflict. And, while it is a tragedy, I also see it as a chance to learn. I think most people going to be split on how to approach this subject, and I would be very curious as to what others think about it. My own thought is that the true professional must constantly balance their obligations to their employer or service against their personal experience, knowing that a certain amount of empathy and ownership is required in order to process wartime events in a way that is both humane and just.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. This post was inspired by Tyrell Mayfield who, speaking on his own experiences in Afghanistan stated, “I’m personally vested, which is different than a professional obligation.”

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

#Profession and 'New Model Army'

In an attempt to procrastinate from writing my thesis, I recently read Adam Roberts’ New Model Army. It is a sci-fi story centred on the narrative of an unnamed protagonist who deserted from the British Army but is now a member of a ‘New Model Army’ (NMA) called ‘Pantegral.’ The Pantegral NMA is an amorphous group organised around democratic ideals (for example, its members vote for courses of tactical action during a battle) and use a wiki for communication and coordination. In a sense it is a ‘crowd sourced’ army based on the equality of its members; all of whom have a vote about how the NMA is run and how battles are fought. The story is set in a dystopian future where secessionist Scotland is at war with the rest of Britain and hires the NMA as its armed force. Here’s an extract from the book that gives a flavour for what NMA is all about:

Lets say our eight thousand men, coordinating themselves via their wikis, voting on a dozen on-the-hoof strategic propositions, utliizing their collective cleverness and experience (instead of suppressing it under the lid of feudal command) — that our eight thousand, because they had drawn on all eight thousand as a tactical resource as well as a fighting force — had thoroughly defeated an army three times our size. Let’s say they had a dozen armoured- and tank-cars; and air support; and bigger guns, and better and more weapons. But let’s say that they were all trained only to do what they were told, and their whole system depending upon the military feudalism of a traditional army, made them markedly less flexible; and that each soldier could only do one thing where we could do many things. Anyway, we beat them.

The underlying assumption in the novel was that the NMA consisted of anyone that wanted to fight and that the wiki was practically a ‘deus ex machina’ that suddenly made the amorphous mass an ‘army’ that had the skills and knowledge to take it to the British and win. On the other hand, the British Army was considered ‘feudal’ and inflexible by comparison; and that these very characteristics were what made it less effective on the battlefield than the NMA.

The book painted an interesting backdrop against which all the articles within the #Profession series can be examined, and enables the extrapolation of the fundamental prerequisites to becoming a ‘profession’. There were three key themes about professionalism that leaped out at me while I was reading the book:

- ‘Fighter’ versus ‘Professional.’

- Professionalism and accountability.

- Pendulum of professionalism.

‘Fighter’ versus ‘Professional’

Mike Denny’s article discusses the issue of when a ‘fighter’ becomes a ‘professional.’ He argues that a soldier’s ability to make autonomous decisions, based on extensive knowledge and experience, is what separates the ‘mere fighter’ from the ‘professional.’ A fighter requires some validation or direction from others to proceed with a course of action, while the professional has the confidence to make a decision on their own that is relevant to their assessment of the situation. Based on this assessment, the NMA does not have any professionals because decisions are made by the ‘hive mind’ in the context where quantity (number of votes) trumps quality of decision. The NMA soldier cannot act alone, despite being able to ‘do many things.’

Dedication to learning the art (and craft?) of war is imperative.

Our Pantegral protagonist also criticises the British Army for being feudal and inflexible. However this ignores the concept of ‘mission command’ that is central to the command and control paradigm of many modern military forces. Originally conceived as an enabler for seizing the intiative versus set piece battles, ‘mission command’ (auftrakstaktik for the purists) relies on professionalism and trust — junior leaders must understand commander’s intent and have the expertise and experience to know when to seize the initiative rather than wait to receive an order to take action[1]. Sometimes, as Denny argued, it might just require breaking some rules! As many of the authors in the #Profession Series pointed out, merely joining the military does not make one a ‘professional;’ in the same way that being able to fix some dodgy plumbing based only on YouTube DIY videos does not entitle you to call yourself a ‘plumber.’ Dedication to learning the art (and craft?) of war is imperative. I doubt that such an ethos exists within a Wikipedia/Google-powered NMA.

In order to have accountability, there must be an identifiable entity that has made a decision and, if necessary, against whom some remedial or punitive action can be taken…

Professionalism and Accountability

Many contributors to the #Professional discussion also highlighted the ethical aspects of professionalism. Dr. Rebecca Johnson discussed the obligation to serve someone other than the people who purport to be part of the profession (no self-licking ice cream cones here) and the need to maintain the trust of ‘the people;’ which implies some measure of accountability to ‘the people.’ In order to have accountability, there must be an identifiable entity that has made a decision and, if necessary, against whom some remedial or punitive action can be taken in relation to the decision made.

The NMA narrator derides the ‘feudal’ nature of the British forces. This attitude seems founded on the hierarchical, rank based and seemingly inflexible command and control structure in conventional military forces. This is subsequently compared with the flat organisational structure of the NMA, where all members are regarded as ‘equals.’ This may be good for fostering a sense of belonging and unity, but does little to enhance professionalism. The flat organisational model of the NMA, coupled with the ‘everyone is equal’ culture results in the diffusion of responsibility for the course of action selected. When the primary criteria for a decision is majority rule, holding the decision-makers to account becomes difficult.

As my drill sergeant was fond of reminding my course during our initial training course, ‘you may be defending democracy, but this [the military] is not a bloody democracy!’ The reason is clear — professional organisations require a hierarchical structure through which values and standards are enforced; ‘the knowledge’ passed on; and direction given. Accountability for decisions is relatively clear in the profession of arms — the commander may bask in the glory; but must also bear the burden of any criticism.

Pendulum of Professionalism

Various arguments were made throughout the #Profession series about the relative nature of professionalism. Roster#299 argued that ‘[t]he military is a profession that adjusts its level of professionalism according to how much it is being used;’ with military forces generally being more like a profession in times of relative peace and less like a profession in times of war. This is consistent with the view proposed by Dr. Don Snider (via Nathan Finney) that professions can ‘die;’ and that merely ‘[w]earing a uniform or getting paid to perform a role does not make someone a professional.’ Angry Staff Officer goes further by saying that ‘just giving a man a gun and pointing him towards the enemy does not make him a soldier’. Based on these criteria, members of the NMA are not professionals — they wear a uniform, get paid, and fight some battles. You might as well hire some Halo cosplayers [2]! You won’t get much warfighting professionalism for your buck.

An individual is inducted into a profession after an assessment of skills and knowledge that are central to the profession (call it basic training). This is just the beginning of a long professional journey along a road that never ends — unless you chose to stop (ie retire or are dismissed). The professional may ‘die’ along the way if they do not make the effort to invest in maintaining and improving the skills and knowledge fundamental to the profession of arms. Dr Simon Anglim emphasises the importance of continuing education in maintaining standards within a profession.

…small bands of fighters have, at times, overcome larger and better equipped forces.

Going back to the scenario at the start of this post, our Pantegral protagonist emphasised that a small NMA force defeated a much larger (three times bigger), and better equipped element of the British Army. This scenario is reminiscent of some real world experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan — small bands of fighters have, at times, overcome larger and better equipped forces. Any attempt to identify one causal factor leading to the defeat of the larger force is difficult, but I might humbly posit a possible consideration: the larger, better equipped force is in professional decline. Perhaps the force is no longer dedicated to understanding and studying warfare (its width, depth and context: Michael Howard).

Perhaps the key to avoiding such defeat in the future is to invest in those leaders who have dedicated themselves to understanding the profession of arms (strategy / military history), and who are unrelenting in their pursuit of self-improvement. These individuals will be the touchstones for maintaining the professionalism of military forces, as they lead soldiers/sailors/airmen who many not be as dedicated to the profession, into an unforgiving and binary environment characterised by life or death; victory or defeat.

The Proprietor of ‘Carl’s Cantina’ is an Australian military officer who has served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Proprietor is an Associate Member of the Military Writers Guild and is currently writing a thesis on Australian civil-military relations. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the Australian Defence Force.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] I thought I’d throw in the German term for the purist strategist, just as I’d throw in a Latin term for the purist lawyers! For a discussion on auftragstaktikand its modern utility, see John T. Nelsen II, ‘Auftragstaktik: A Case for Decentralised Battle’ Parameters, September 1987.

[2] As the proud owner of a partially constructed (and therefore not yet vetted by the 501st Legion) Stormtrooper outfit, I just want to make it clear that I have nothing against cosplayers!

Correct Answers and #Profession

Last week the Army War College released a study about military officers lying on a regular basis [1]. These lies include everything from misreporting training status to inflating performance reports. But, how much of this is blatant lying versus simply providing the “correct” answer?

Providing the “correct answer” is something that begins the first day of basic training, and it becomes an institutional norm. For instance, how many times has an entire squad of basic trainees replied, “YES DRILL SERGEANT,” to a question posed by their drill sergeant? This is the “correct” answer. The correct answer isn’t “No,” or “Yeah,” or “I don’t remember.”

U.S. Air Force Academy Form “O-Dash-96"

In my own experience, I found that basic training reinforces particular behavior and norms. For instance, new (basic) cadets at the Air Force Academy are given a survey after their first or second meal at the school. Officially, its an Air Force Form O-96, and contains six simple questions about the meal. The cadre instructs the basic cadets to fill out this survey. How was the food service? How was the attitude of the waiters? How was the waiter service? How were the beverages? What size were the portions? And finally, how was the meal? Not knowing the cadet system, as a young basic cadet, I answered the questions truthfully and honestly. How was the service? I thought it was slow! What was the portion size? I thought it was oversized. How was the meal? I thought it was unsatisfactory. I found out very quickly that these were not the “correct” answers. The correct answers (in order of the questions) were: fast, neat, average, friendly, good, good. Every cadet learned that these were the answers to the six questions on the form. It had to be filled out in this way. No other way was acceptable. This simple list of six answers is an institutional norm, a meme, which transcends every Air Force Academy class. But, this sort of correct behavior goes beyond basic training and tradition-building exercises, it can be found in most facets of military life. The “correct answer” is not so much the answer to the question, as it is a way of teaching conformity, uniformity, and mental discipline. Despite being deceptive, these are all characteristics of a well-trained military.

…the lessons of basic training don’t clearly elucidate the dichotomy between the truthful answer, and the “correct” answer, which may instill a culture that finds it acceptable to provide the “correct” answer all of the time.

Now, the lessons of basic training don’t clearly elucidate the dichotomy between the truthful answer, and the “correct” answer, which may instill a culture that finds it acceptable to provide the “correct” answer all of the time. But, this issue isn’t confined to the military alone. Large, complex, institutions are beset with internal systems, procedures, and layers of bureaucracy. Because of this, often the “correct” answer trumps the “truth.” How many times in my life have I given the “correct” answers versus the truth? It goes beyond procedure and formalities; we actually see this inconsistency all the time in our daily lives. For instance, I was on the phone with my bank recently and they wanted to know the color of my car (my security question). Well, I thought, I have two cars — one is black and one is blue. But, after much discussion, I found out that this is not the “correct” answer. The correct answer is silver, which was the color of the car I had when I created that account. But, this answer is not the truth, hence, the contradiction. But, the very point of the question is not to find out the color of my car, just like the point of the survey was not to find out about Basic Cadet Maye’s opinion of the meal. The point of the security question was to validate my identity. The point of the survey was to indoctrinate and train.

Oftentimes the “correct” answer saves you time and energy, and oftentimes it’s a matter of priorities. Providing the “correct” answer helps you focus on the mission you deem to be the most important for your people. That is not to say that the “correct” answer is always the best answer. But, it in a culture that routinely trains people to provide the correct answer, it can be difficult to distinguish the difference between the two.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the US Government or the Department of Defense.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] “Lying to Ourselves: Dishonesty in the Army Profession,” by Leonard Wong and Stephen Gerras, 2015, Strategic Studies Institute, Available from:http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=1250

Don’t Expect #Professional Status in Civil Society

While many in uniform have earned the title of “professional” through commitment to excellence, high ethical standards, and service in defense of the nation, more work has to be done to convince those outside the service. As professionals, we must teach children, friends, and other Americans about military professionalism. We should continue to walk the path of the warrior-scholar and adopt an attitude of excellence in this profession.

The Military is not the Sole #Profession on the Battlefield

The framework of the military as a profession heightens the existential nature of the identity and therefore presents a heightened challenge when eventually the uniform is retired. Now the individual must answer to his or her self as one. Who am I post my profession? The military is not alone in this challenge. It has a most unlikely counterpart: the humanitarian aid worker who also serves in war.

The Rise and Fall of U.S. Naval #Professionalism

"Whether the military is a profession depends on definitions that remain moving targets. An overly-inclusive definition would classify a street gang with rudimentary training and a code of conduct as professional while a strict definition produces essays like Jill Sargent Russell’s “Why You’re Not #Professionals,” where, as others have pointed out, if applied to other professions (like my own) renders a lawyer that specializes in employment discrimination unprofessional because he wouldn’t know how to provide effective estate planning, no matter how successful his record in the courtroom."

Confessions of a Struggling #Professional: Summarizing the #Profession series

The reason I enjoy continuing this conversation on The Bridge is because many of our “professional” counterparts are interested in having it. I think I have a better idea about where I stand, and where our military stands with respect to this conversation and I urge all of you to pursue a professional standard and think about the ethical requirements that it entails.

Thoughts on our #Profession

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin inflamed anti-slavery sentiment leading up to the American Civil War. When she met President Abraham Lincoln in 1862 during some of the darkest days of that conflict, he remarked:

So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.

Reading The Strategy Bridge #Profession posts touched off by Dr. Pauline Shanks Kaurin’s tweet brought that famous quote to my mind. There has been no lack of discussion on the topic of military professionalism since that first post, whether it was here, Twitter, Facebook, or various strategy and national security listservs. Since I had the good fortune of getting my opinion in before the fracas started, The Bridge was kind enough to offer me space to pen some overview thoughts. After having a chance to read the excellent series of submissions here on the topic, I find myself still dealing with three nagging questions.

Are we a profession?

Jill Sargent Russell’s piece ruffled a lot of feathers with a flat “no.” In many of the ensuing responses, I noticed a recurring tautology: we’re members of a profession because we say we are; because we have offices with “profession” in their title; or because Dead White Guy said so.* Huntington’s model got invoked a few times in response, which is problematic when you remember that he, a) created his model solely to support a broader position about civil-military relations, and b) didn't consider NCOs and enlisted soldiers to be professionals. Another problematic assertion was a claim of professionalism derived from the military requirement to potentially give one’s life in service to the nation. This strikes me as true, but irrelevant; I cannot think of any profession that has “sacrifice” as a key element of professional identity.

I can’t agree with Russell’s contention that members of the military don’t fit under an overarching rubric of profession because not every servicemember stabs a terrorist in the face before breakfast.

Nevertheless, I can’t agree with Russell’s contention that members of the military don’t fit under an overarching rubric of profession because not every servicemember stabs a terrorist in the face before breakfast.** Although the wielding of violence is not a routine occurrence for most members of the military, we select and train service members with the expectation that they may be called upon to exercise that franchise. No one expects a podiatrist to step in and perform complicated neurosurgery; but the average observer would expect said specialist to perform basic medical procedures in a situation where they were called for.

Is there a difference between “a profession of arms” and “service professions”?

Many of The Bridge authors conflated the original question of military as a profession with the idea of the Army as a profession. Given that the majority of responders were Army officers, this is neither surprising nor inappropriate. “Write what you know” is a recurring tenet in most official and unofficial guides to professional writing (see what I did there?) But it does beg the question of whether we should be looking at the profession of arms as a whole or individual service professions. The difference between the two has implications for everything from shares of the defense budget to concepts of joint warfare.

The difference between the two [profession of arms or individual service professions] has implications for everything from shares of the defense budget to concepts of joint warfare.

A strong argument for the concept of service professions as opposed to a profession of arms comes from @InTheInfantry’s “As Professional as Circumstance Allows.” His piece deftly spells multiple ways that the Army has altered professional standards over the past decade in response to the iron calculus of protracted war. Many of his critiques were familiar to Army officers who read and commented on them; other service officers were less receptive:

When do we become professionals?

If we are a profession, then there must be professionals in it; but simply entering into a professional career field is not enough to confer that title on someone. There has to be a mechanism whereby someone demonstrates professional ability and skill. For doctors, it’s typically board certification; for lawyers, it’s passing the bar. Mike Denny’s piece posits that cutoff point for the Army as occurring “when an individual soldier attains enough knowledge and expertise to demonstrate an ability to act and make decisions autonomously.” But when, exactly, does that happen?

Is it combat? Surely not, as there are generations of Cold War soldiers who we would describe as professional, yet never “saw the elephant”.

Is it completion of a certain level of PME? Given the number of people who reference PME by saying, “it’s only a lot of reading if you do it,” this would seem a dubious milestone.

My insistence on a fixed benchmark for professional status may seem downright Jominian for such a Clausewitzian notion. But it’s also a reflection of our accountability to civilian leadership for our conduct and performance.

My sincere thanks to everyone who contributed to this discussion and made it a model for future conversations!

* I choose not to link to specific instances of any of these because I have no interest in starting a blog/Twitter fight.

* My absurd oversimplification, not hers.

This post is provided by Ray Kimball, an Army strategist who thinks he’s a professional…but how would he know? This post reflects his opinions, not those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or Section 31.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Views on the #Profession from the Professional

My take-away from this most recent series on The Bridge, and the resources like those detailed above, is that a profession — and those individuals of which it is composed being labeled professionals — is a very fluid thing. It is more fluid than we care to admit. Wearing a uniform or getting paid to perform a role does not make someone a professional.

#Professional Education and the 21st-Century Military

Education is vital to the 21st century military, and likely to become more so. Whereas training aims at instilling, maintaining and improving skills, and, in the military, preparing personnel physically and psychologically for combat operations, professional education instills knowledge. Not just knowledge for its own sake, either — the aim is not just filling somebody’s brain with facts or figures, but to expand their understanding of the world, how it works and their place in it, with the hope — and often that is all there is — that this will influence the decisions they make when their training is applied in real life. This is why most professions have at least some ethical education as part of their induction process, to get people to think about why they do things beyond just how they do them, and how and why their actions might impact on others.

Samuel Huntington can be disputed on many things, but he is right in arguing that an important component of any profession is awareness that it is a profession, a group with specialist knowledge differentiating it from the rest of society, and that this specialism gives them a duty of service to society as a whole. It is the education they receive, the ‘why’ they are do things, which glues together the different bits of training professionals get into a coherent whole and informs them of their social role and duty.

Yet, a reading of these books shows many still trying to impose the old Maoist model of ‘revolutionary warfare’ on what the Taliban and ISIS are doing…

The military are professionals in applying deadly force, or the threat of deadly force, on behalf of their government in pursuit of that government’s policy aims. The more professional the military, the more seriously it takes this role, the more efficient it will be and the better the chances of achieving those policy aims, the most important of the ‘whys’ shaping the military and what it does from day to day. As Clausewitz, though often misquoted, said, all war is explicitly political, so anything done by any member of the armed forces on any military operation will have political intent and implications.

This is important on several levels but particularly in the ‘complex’ scenarios seen since 9/11 and interventions into genuinely multi-cultural, multi-tribal and multi-lingual societies of the sort found in the Middle East, Africa and across much of Asia or even Europe. A number of recent books on Afghanistan, particularly those by Emile Simpson and Mike Martin, present the idea of competing narratives, the notion that you have an accepted idea of what the war you are in is about, why it is happening, who the good guys are, the bad guys are and who is going to win, and how, but that other people in that same war may have radically different views on all these same things, and this may include your friends as well as your enemies.

Yet, a reading of these books shows many still trying to impose the old Maoist model of ‘revolutionary warfare’ on what the Taliban and ISIS are doing, seeing some kind of single, all pervasive ‘insurgency’ in which everyone who shot at Allied forces in Afghanistan, for instance, was ‘Taliban’. The reality is a complicated patchwork of tribal, family and criminal networks which may be fighting viciously one month, and working as allies the next, into which NATO arrived only a decade ago. Such networks are far more influential than state governments across large parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, yet Mike Martin and Frank Ledwidge in particular cite numerous examples of the kind of embarrassing and occasionally self-defeating things which happen when supposedly professional militaries did not appreciate this and the knowledge not passed on.

It is therefore essential that service personnel get a degree of historical, political and cultural education about the nature of the people they are working with and the world in general. If, at the very least, forces develop a good, accurate understanding of why the enemy sees the world the way he does — and he may, of course, see it far, far differently from the way that they do — then they are some way along the road to defeating or at least neutralising him. If they understand the culture and worldview of the people which they operate among, particularly during interventions and insurgencies, it will help immensely in gaining local confidence and cooperation and improve efficiency in things like intelligence gathering.

Doctrine acts as the bridge between theory and practice and is separate, yet interlinked with both…

Another important component of the ‘why’ is that each armed force goes about its business in the way it does. This, of course, is ‘doctrine’ — a word frequently translated as ‘teaching’ and so referring explicitly to education. The concept of ‘doctrine’ has been transferred from religion to politics and then the military and denotes any attempt to create a coherent, systematic way of doing things, usually taking the form of an officially endorsed set of recommended actions for any given situation.

Doctrine acts as the bridge between theory and practice and is separate, yet interlinked with both: theory explains doctrine, practice carries it out. Doctrine is the ‘why’ for most military people, more of the ‘glue’ which ties all professions’ training and acquisition together into a coherent whole which works better than the sum of its parts. Education is particularly important to the US and British militaries because of their attitude to doctrine, a general philosophy in both forces being that doctrine should not be too prescriptive, but rather a set of guidelines which can and must be adapted to whatever situation it comes up against.

US and British military doctrine hinges (in theory) on mission command: fundamentally, giving a commander an objective, a time to achieve it by, and then trusting him to get on with it without too much supervision, adapting to the situation as they see fit. Mission command requires all commanders to have a sufficient intellectual breadth to appreciate the overall mission of the entire force, how they fit into it and the impact, for better or worse of certain actions on the enemy. It is important, therefore, that commanders have some knowledge of the evolution of strategic theory and military history. Understanding strategic theory is important because it answers another set of ‘why’ questions — why are we, a particular arm of service, called upon by our political masters to do the particular jobs we do, and why do we go about them in the way we do? Might there be other ways of doing these things, and if so, are they viable? A really professional officer, of any service, should be asking these questions constantly in order to help his service adapt and evolve not only day to day on the ground, but decade to decade as history throws new shocks at it.

Military history is vital too. History is accumulated vicarious experience, allowing us today to learn from what others did before. Serious, instructive history is about the study of change and process over time, another way of explaining how and why things happen now in the way that they do. It also provides guidelines for what we might be doing now — history does not repeat itself, but it does, occasionally rhyme, and so while a good knowledge of military history probably will not teach explicit lessons for today’s armed forces, if understood properly, it will send important messages. There is also something more visceral about military history, perhaps one reason why the British Army places such great stock on recording regimental histories, the RAF on Squadron histories, and why the US Marine Corps makes a knowledge of Corps history a requirement for all its recruits and trainee officers. It reminds people they are part of something bigger and older than they are, in which those going before have set expected standards of conduct and behaviour which they are expected to keep up; it also shows people that there are few things which are completely unprecedented or insurmountable, that others have faced apparently impossible things in the past and overcome them. For any profession, including the military, history serves an inspirational purpose and perhaps teaches humility as well.

Education is vital to the 21st century military, and likely to become more so.

The final argument is more contemporary. 21st century Western military operations combine ‘joint’ with the ‘comprehensive approach’, requiring the three services to act in cooperation with each other and, of course, with the forces of allies, be they local or part of NATO; furthermore, with interventions and counterinsurgencies, civilian agencies may be involved as well. This is not without its controversies, but necessitates some understanding and appreciation of how other agencies work, and in many cases, how the armed forces of allies work. This does not just involve observing them now but also knowing something of their past, which might give insights into what they are capable of and prepared to do, so making planning a lot smoother, and cooperation on the ground a lot more effective. It will also, hopefully, reduce the chance of cultural clashes, particularly between the military and civilian agencies that might have widely divergent reasons for why something is happening and what they are going to do about it.

Western forces are facing a complicated and frankly sometimes rather awkward operational environment in the 21st century. All our servicemen, be they airmen, sailors, soldiers, or marines, are going to need the breadth of knowledge, vision, and understanding in order to do their jobs in this environment. Education is vital to the 21st century military, and likely to become more so.

Dr. Simon Anglim is a Teaching Fellow in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. He has authored over a dozen papers on insurgency and special and covert operations and the role of educators in the British Army on combat operations. His book, Orde Wingate: Unconventional Warrior was published in October 2014. He tweets regularly at @sjanglim.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The Gun Doctor & #Professional Military Character

In early 1916, Europe was engulfed in The Great War. The rapid campaign expected in the summer of 1914 had degenerated into something unexpected, a long and almost siege-like struggle. While the United States proclaimed neutrality, the U.S. Navy suspected things would get worse and they would eventually either need to protect the American coast, or carry an army across the Atlantic after a mass mobilization. They began to prepare a group of volunteers who expressed interest in joining the naval services. It began with a series of lectures, including subjects like coastal defense tactics and torpedo boats, and a short period aboard a ship at sea.

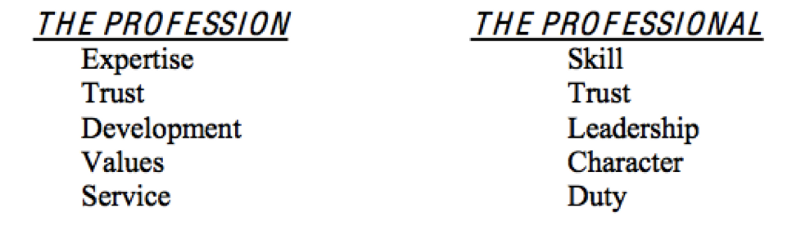

VADM William S. Sims, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe

Captain William Sims was asked to prepare a lecture for the Naval Volunteers on the subject of “military character.” Sims was well known in the service. He had ledthe gunnery revolution a decade prior, at one point earning him the nickname “The Gun Doctor”. He was also a leading voice in the development of modernbattleships. He had spent some time at the Naval War College as a student, and was kept on as an instructor before returning to the fleet. During the war he would command all U.S. Naval Forces in Europe, the Navy’s command equivalent to General Pershing’s on land.

The subject of professionalism is central to much of Sims’ writing, both before the war and after returning home to assume responsibilities as the President of the War College. From the importance of personal professional study to the elements of mission command to the need for constant military innovation, he spent a good deal of time thinking about the subject.

…a central but often overlooked element was the importance of self-awareness. Professionalism requires a constant personal net assessment, or “estimate of the situation.”

What did Sims believe were the professional and ethical responsibilities of a military leader? In his view a central but often overlooked element was the importance of self-awareness. Professionalism requires a constant personal net assessment, or “estimate of the situation.” This is what he told the Naval Volunteers who had gathered with the knowledge that they might soon leave their civilian lives and take on the mantle of military leadership:

It seems almost incredible that there should be men of marked intellectual capacity, extensive professional knowledge and experience, energy and professional enthusiasm, who have been a detriment to the service in every position they have occupied. They are the so-called “impossible” men who have left throughout their careers a trail of discontent and insubordination; all because of their ignorance of, or neglect of, one or many of the essential attributes of military character.

I knew one such officer who was a polished gentleman in all respects, except that he failed to treat his enlisted subordinates with respect. His habitual manner to them was calmly sarcastic and mildly contemptuous, and sometimes quite insulting, and in consequence he failed utterly to inspire their loyalty to the organization.

A very distinguished officer said after reaching the retired list: “The mistake of my career was that I did not treat young officers with respect, and subsequently they were the means of defeating my dearest ambitions.”

The services of this officer, in spite of this defect, and by reason of his great ability, energy, and professional attainment, and devotion to the service, were nevertheless of great value.

Both qualities and defects of course exist in varying degrees. These sometimes counterbalance each other, and sometimes the value of certain qualities makes up for the absence of others.

…no matter what other qualities an officer may possess, such success can never be achieved if he fails in justice, consideration, sympathy, and tact in his relations with his subordinates.

Some officers of ordinary capacity and attainments have always been successful because of their ability to inspire the complete and enthusiastic loyalty of all serving with them, and thus command their best endeavors; but no matter what other qualities an officer may possess, such success can never be achieved if he fails in justice, consideration, sympathy, and tact in his relations with his subordinates.

VADM Sims with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt

Such men are invaluable in the training of the personnel of a military organization in cheerful obedience, loyalty and initiative; and when these qualities are combined in a man of naturally strong character and intellectual capacity he has the very foundation stones upon which to build the military character.

The pity of it is that so many men of great potential power should not only have ruined their own careers, but have actually inflicted continuous injury upon the service, through neglecting to make an estimate of the situation as regards their characters and through neglecting to use their brains to determine the qualities and line of conduct essential to success in handling their men, and thus failing to reach a decision which their force of character would have enabled them to adhere to.

Such a reasoned process applied to the most important attribute of an officer, namely, his military character, would have saved many from partial or complete failure through the unreasoned, though conscientious, conviction that it was actually their duty to maintain an inflexible rigidity of manner toward their subordinates, to avoid any display of personal sympathy, to rule them exclusively by the fear of undiscriminating severity in the application of maximum punishments, and such like obsessions.

It would appear that such officers go through their whole career actually guided by a snap judgment, or a phrase, borrowed from some older officer…Though they have plenty of brains and mean well, their mistake is that they never have subjected themselves and their official conduct to any logical analysis.

It would appear that such officers go through their whole career actually guided by a snap judgment, or a phrase, borrowed from some older officer, such as the precepts quoted above. Though they have plenty of brains and mean well, their mistake is that they never have subjected themselves and their official conduct to any logical analysis. Moreover, they are usually entirely self-satisfied, and frequently boastful of their unreasoned methods of discipline; and they usually explain their lack of success by inveighing against the quality of the personnel committed to their charge.

All this to accentuate the conclusion of the war college conference that: “We believe it is the duty of every officer to study his own character that he may improve it, and to study the characters of his associates that he may act more efficiently in his relation with them.”

This, then, is the lesson for all members of our military services. Let us consider seriously this matter of military character, especially our own. Let us not allow anybody to persuade us that it is a “high brow” subject, for though military writers confine their analysis almost exclusively to the question of the “great leaders,” the principles apply equally to all individuals of an organization from the newest recruit up.

Reprinted by permission of The Naval Institute Press, from Benjamin Armstrong, Editor, “21st Century Sims: Innovation, Education, and Leadership for the Modern Era” (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015). The book, where you can find much more of William Sims writings on the professional ethic, is available 15 February 2015 in paperback and e-book.

This post was provided by BJ Armstrong, a naval aviator currently serving in the Pentagon. He is a member of the Naval Institute Editorial Board and a PhD Candidate in War Studies with King’s College, London. His first book, with leadership and professional lessons from the writing of Alfred Thayer Mahan, is “21st Century Mahan: Sound Military Conclusions for a Modern Era.”

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Ethical Requirements of the #Profession

Obligations of the Professional, the Profession, and the Client

It’s been fairly well established elsewhere, and by others in this series, that the military holds itself to be a profession. Given the generally high level of deference most policy makers show military leaders’ judgment and the unparalleled ways in which we allow the military to self-regulate, it seems pretty clear — to me at least — that the American people agree.

What Do We Mean by ‘Ethics’?

The question then, is what ethical responsibilities military members hold as a result of being professionals. Here it’s important to differentiate between morals and ethics. Service members hold both moral and ethical responsibilities, but it’s useful to understand them distinctly, even if they interact within one person. Briefly, what is moral can be understood as ‘that which strengthens the community.’ Humans are inherently social beings, and morality is what allows us to flourish together amid all the frustrations and competing interests of communal life. Conversely, that which is immoral can be understood as ‘that which erodes (undermines, weakens) the community.’

In one sense ethics is the study of morality; it’s the academic discipline many of us learned at school. Its meaning differs when applied to the professions. In this context ethics is understood as that which maintains the standards of the profession. Just like morality ensures human flourishing is possible in community, ethics ensures flourishing is possible in a given profession.

What Do We Mean by ‘Profession’?

It follows then, that in order to understand the military’s ethical responsibilities, we have to understand the profession’s requirements. The Army tackled this question back in 2010 under General Dempsey’s leadership at TRADOC in The Profession of Arms. They identified five core characteristics of professions, which track with five core traits of professionals.

The Profession of Arms, 2010, 5.

In a nutshell, a profession is characterized by maintaining a high level of specialized expertise. For the military, this expertise is the expert use of violence for a political end; for a doctor it would be the expert use of medicine for health. This expertise is used on behalf of a client, who trusts the professional to use her expertise on his behalf. In the case of the U.S. military, the client whose trust must be maintained is literally the U.S. Constitution, though we most often think of the spirit of the Constitution as embodied by the American people and territory — this is why service members take their oath to support and defend the constitution. As long as trust is maintained, the client allows the professional to build and employ her expertise without a high degree of regulation. The professional is the expert, after all, and knows how best to ply her craft.

Since expertise is perishable and must be maintained, professions also require continuing efforts to develop.

In order to build and maintain expertise, professions put a high premium on development. Not just anyone can join a profession. Only those who demonstrate skill and potential for continued growth are allowed in, and each profession has some semblance of a credentialing process to evaluate that skill and potential (that again, is largely self-regulated without overly invasive input from the client). Boot camp, Officer Candidate School, and Basic School are illustrations in the military context. Law school and the BAR exam are illustrations in the legal context. Since expertise is perishable and must be maintained, professions also require continuing efforts to develop. These can be technical promotion requirements, annual fitness tests and rifle qualifications, and professional military educational requirements.

To ensure the profession remains focused on its client, this development of expertise must be tied to foundational values that benefit the client. Honor, Courage, and Commitment are the Marine Corps’ values that resonate with the American constitution and people. The Hippocratic Oath is an illustration of the values the ground the medical profession. Without these values, the professional may be tempted to prioritize expertise over the client and undertake all sorts of ‘expert’ actions that harm the client more than they help. The final piece of glue that binds a profession to its client is the characteristic of service. Businesses exist to provide profit. Bureaucracies exist to provide efficiency. Professions exist to provide service to the client. When they stop doing this and rather focus on serving themselves or chasing profit, they cease to be a profession.

The Military’s Ethical Responsibilities

So then, if those are the requirements of professions generally, and the profession of arms specifically, what must service members do to maintain the standards of the profession? What ethical responsibilities do service members hold?

I’ll offer five. It’s not my intent to evaluate how well the services are doing in meeting each of these ethical requirements, but anyone who works around the military will see pretty quickly that the services are stronger in some areas than others.

Innovation — tactical, doctrinal, and strategic — is essential to maintaining and developing expertise in a complex, rapidly changing environment.

1. Service members have an ethical responsibility to maintain and develop their expertise. This applies not only to the individual service member, but also to the profession as a whole. Innovation — tactical, doctrinal, and strategic — is essential to maintaining and developing expertise in a complex, rapidly changing environment. Mike Denny is right when he notes that #Professionals Know When to Break the Rules. Why? Because expertise requires judgment, and sometimes that judgment tells the professional that the textbook answer won’t work in a particular set of circumstances. The professional accepts the consequences of bucking doctrine, tradition, or culture, and contributes to the profession as a whole by doing what his expertise tells him is right

…the American people have lost confidence in the services’ ability to prevent and punish sexual assaults on their own.

2. Service members have an ethical responsibility to maintain trust with the American people. One might immediately jump to Abu Ghraib, the desecration of corpses, or other battlefield crimes to illustrate this point, but arguably the services’ seemingly lackadaisical attempts to eliminate sexual assault in the ranks is more telling. Congress was willing to allow the UCMJ to adjudicate potential breaches of combat ethics and the law of armed conflict; however, it is considering removing UCMJ authority from commanders in sexual assault cases. While this likely won’t happen, the 2015 NDAA calls for removing the statute of limitations on sexual assault prosecutions as well as a mandatory dishonorable discharge for certain sex offense convictions. Why? Because the American people have lost confidence in the services’ ability to prevent and punish sexual assaults on their own. Trust, once lost, takes time to rebuild. It is every military professional’s responsibility to not lose that trust in the first place and repair it where necessary. That is, unless the profession doesn’t mind losing the significant latitude it currently holds to regulate itself.

Leaders have the responsibility to provide the necessary top cover for subordinates to practice, fail, and grow.

3. Service members have an ethical responsibility to develop those junior to them. Of all the requirements of the profession, this is the one my students tell me is most routinely ignored. Monitors will talk to service members about the importance of broadening opportunities and key developmental assignments, but the last 13+ years of war have bred some leaders to focus on execution of tasks at the expense of cultivating subordinates’ skill and judgment. Leaders must fight this temptation along with the tendency to micro-manage and crush failure (failure being an essential element of innovating in response to an increasingly complex environment and enemy). Micro-managing and the zero defect mentality make perfect sense for an individual in the short term, but they are disastrous to the profession over time. Leaders have the responsibility to provide the necessary top cover for subordinates to practice, fail, and grow. Subordinates have the responsibility to show initiative and sometimes fail in order to grow.

4. Service members have an ethical responsibility to uphold American values while leveraging their expertise. There’s been a lot of talk lately about the civil-military divide. While Fallows was perhaps less groundbreaking than some may claim, he highlights the challenge of upholding a nation’s values when the natural ties that would transmit those values have weakened. While it is easy (and fair) to blame Americans for failing in their civic responsibility to know about the wars their country wages on their behalf, it is the professional’s responsibility to consistently ‘go back to the well’ to ensure his decisions and actions resonate with the nation he serves. In those moments when what is ‘right’ contradicts what is tactically effective, efficient, or practical, the professional must search for a way to leverage his expertise in the lethal use of force in a manner that upholds American values. If he ignores American values in the pursuit of lethality, he may be a very effective killer, but he is not a professional.

5. Service members have an ethical obligation to serve. This seems obvious, but the current uproar over retirement, education, and medical benefits highlights that segments of our military place a monetary value on their time in uniform. To be absolutely clear — I fully support service members receiving the benefits they were promised when they entered service. This is part of the nation maintaining the military’s trust in us. Still, a profession exists to serve someone other than the professionals. Leaders who recognize and value that in their units and subordinates do better by the profession as a whole than those who do not.

I often struggle with writing about issues of military ethics because statements like the five ethical requirements listed above seem so obvious. At the same time, having taught hundreds of field grade officers over the past six years I know they struggle with meeting these ethical obligations to their subordinates and the nation. This is not because they lack motivation or ability, but because the institutions of the profession at times make it difficult — if not impossible — to do so. While this series of posts examines the obligations of the military professional, it is equally important to examine the obligations of the profession to its members and of the client to those who have chosen to serve on its behalf.

This post was provided by Dr. Rebecca Johnson, an Associate Professor of National Security Affairs at Marine Corps University’s Command and Staff College. Previously, she taught as a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Georgetown Public Policy Institute at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. She completed a Masters in Divinity at Wesley Theological Seminary with concentrations in ethics and world religions in 2010. This article was the basis for her chapter in Redefining the Modern Military: The Intersection of Profession and Ethics. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the DoD, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Questioning Military #Professionalism

On a rainy day in January I was doing what I usually do in the month of January: preparing for my philosophy class (Military Ethics) by picking the brains of smart and experienced people on Twitter about the class topic for the day. Like all good ideas, I appropriated this strategy from fellow military ethicist Rebecca Johnson, who hosted a military ethics discussion on Twitter with the hash tag #METC. I posed some questions about whether the military was a ‘profession’ and if it was, how that shapes ethical values. What followed was an energetic discussion that I mostly moderated, without weighing in — as is my practice in class.

To provide some context for the other posts in this series that stemmed from my questions, I want to provide some context — in other words, why I think they are important and some of my own thoughts to further the discussion.

First, why think about the military as a ‘profession’ and what does that mean? I am not asking whether members of the military can display a sense of ‘professionalism,’ that is doing your job well and in accordance with certain basic standards. When I refer to a ‘profession,’ I have some quite specific traits in mind:

A body of expert knowledge, on which basis,

the public accords certain privileges in exchange for,

an understanding that the members of the profession will self-regulate and,

operate for the common or public good.

Historically medicine, law and the clergy were the main professions that fit this bill.

However, another piece here is that the ‘professions’ also have their own code of ethical conduct that is generated based upon the nature and identity of the profession. It is not happenstance that medical professionals claim, “Do No Harm” as an ethical principle; it comes from the very identity of their profession as healers. To talk about the military as a profession is to say that the ethical values (and not simply the laws and procedures to which military members are subject) are generated from the identity and nature of the profession, that is they are not merely contingent or happenstance, but evolve necessarily and organically from the nature of that profession. Loyalty and courage (for example), are not virtues or traits that might be replaced with any other traits; these are essential to being a member of the military and one cannot be a good member of the military and fulfill one’s role without them.

An implication here is that these ethical values do not change as technology changes or as the conditions in which the profession practices changes (even if application changes), because they are rooted in the basic tasks, function and self-regulated understanding of that community of professionals. This provides a certain kind of rootedness and consistency that we can observe across time, and to some degree across culture and context. Being a medical professional means to heal, to be a member of the clergy means to represent and bring the presence of the divine and administer the community of faith in ways that we can recognize as having a great deal of consistency.

In the discussion and subsequent post, Jill Russell raised an interesting point about whether all members of the military are truly members of the profession in this sense. It might seem that the officer corps and possibly non-commissioned officers fit this description, but what about the private on the ground or the lowest level of military member? Doesn’t it seem more like that they are doing a job, for which they are trained and paid?

I take the question to be a more prescriptive or aspirational claim: we ought to think of the military profession in this way; this is the best way to think of the military and its role in society.

Her point raises an important distinction that I think is critical to the discussion. In my view, to ask this question is not a matter of whether it describes some empirical reality of military service in the 21st century. If this is the question, it’s a short discussion and the answer is no, the military is not a profession. I take the question to be a more prescriptive or aspirational claim: we ought to think of the military profession in this way; this is the best way to think of the military and its role in society. But why does this distinction matter? What is at stake in this debate?

If we think about the military as a profession as an aspiration or prescription/goal towards which to work, we can acknowledge two things. First, that the development of the military as a profession, as with other professions, is a work in progress and that the community must continually reflect on their profession, discuss their identity, function and the ethical standards that go with that identity, as well as inculcate new members into this context. In this process, there must be room for questions, critical questioning and reassessing of this identity and the ethical values that derive from it.

Second, it means that the ethical values of the military are rooted and grounded in a way that is fundamentally different than the ethical values of other vocations or jobs, like business, fashion, or child care. If the military is a profession, then the ethical values of the military must be grounded in the nature and identity of the military as a profession.

As for the Professor, I am inclined to think that, the military is in fact a profession (aspirationally) with the trust of the public, tasked with protecting the American homeland and interests by bringing war waging expertise to bear on that function, having been given license to kill and destroy property (amongst other things). There are rigorous and specific requirements for admission and certification to be a member of the profession and the military largely self-regulates with its own justice system to which members are subject and its own ethical code. The new challenges which the military faces, the new contexts in which they wage war, necessitate on-going and critical discussions about the nature and identity of the profession and the ethical values that derive from the profession.

Pauline Shanks Kaurin holds a PhD in Philosophy from Temple University, Philadelphia and is a specialist in military ethics, just war theory, social and political philosophy, and applied ethics. She is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, WA and teaches courses in military ethics, warfare, business ethics, and history of philosophy. Recent publications include: “When Less is not More: Expanding the Combatant/Non-Combatant Distinction;” “With Fear and Trembling: A Qualified Defense of Non-Lethal Weapons;” and Achilles Goes Asymmetrical: The Warrior, Military Ethics and Contemporary Warfare (Ashgate, 2014).

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

#Professional Warfighters

A Historical Perspective on the so-called “Profession of Arms”

An on-going discussion at the Strategy Bridge on the topic of the Army as a profession got me thinking about the general idea of the “profession of arms.” Naturally, I immediately did two things: 1) Looked in the mirror and asked, “Do you even profession, bro?” and 2) Thought of historical precedents, as I always do when posed a quandary. Because of course I want to say that I’m a professional; as an Army officer, it’s like the kiss of death to my career if someone calls me unprofessional in an evaluation. And what would that mean for everyone’s favorite buzzphrase, “Officer Professional Development?” If we’re not professionals, then how do we do OPD (I don’t think most people do it, but that’s another story)?

Bottom line, the Army preaches professionalism ad nauseam but seldom bothers to ask the question of what professional warfighting organizations have looked like in the past. Which leads me to ask…

Most ancient and early-modern wars were fought with unskilled warriors, who relied on mass and fear to overpower their enemies.

What does a professional warfighting organization look like? Well, man has gone to war since the…um…pretty much always, according to archaeologists and historians. Most ancient and early-modern wars were fought with unskilled warriors, who relied on mass and fear to overpower their enemies. The real transition is when a society appoints a certain section of the population to learn war and practice it, for the general good. There have been several instances in history where these professional armies have developed. First off, we have…

Sparta

On the Grecian islands, the city-states developed tiny armies based around the phalanx formation (lots of dudes with pikes and shields forming a tight mass), where warfighting became phalanxes pushing each other around the battlefield until honor was fulfilled, and then they’d go and polish off a few amphorae of wine over the few guys who managed to get themselves killed. Sparta really messed this up for everyone by essentially creating a slave-based economy to support a class of warriors who brought killing into fashion again. Their tactics were designed to destroy the enemy’s phalanx and turn it into a death trap. The mark of a professional soldier is training, and man, did Spartans train. Not only did they train, they built a culture around being good at killing people. The problem became that the other city-states caught onto this idea, too and professional armies began popping up all over the place. Warrior-culture became the vogue (not unlike all things Spartan these days, except for the whole slave thing) and Sparta got out-manned and overrun.

Not pictured: The abuse of children and mass slavery. But sure, call your platoon the “Spartans.”

The whole thing didn’t end well for the Grecian world, as when you make a name as the toughest kid in the neighborhood, all the other tough kids will come gunning for you.

Rome

The next kid on the block to up the ante on professional warfighting was Rome. Rome basically took the Spartan model, added combined arms, the idea of a Republic (ideals beyond the warrior for the warrior to fight for), a set period of enlistment, and a pension. Worked out pretty well for them; Roman legionaries were some of the best soldiers ever seen on the planet, as evidenced by an empire that ran from Britain to Persia. They had organized training, a robust non-commissioned officer corps (the sign of any good army), and a developed force structure (legions). Legionaries could serve their twenty years and retire to a piece of land in the newly conquered territories. Or they could die in battle versus these crazy Germans who kept attacking the frontier. Yup, over-expansion killed the Roman Empire even as its legions fought each other in civil wars. Not a pretty way to go.

"I can’t wait to get my twenty year papyrus…"

Medieval Warfare

So after the Roman Empire fell, warfare veered towards the dude who brought more dudes on horses to the fight. It was the era of knights in shining armor, or, more accurately, knights in really heavy armor on big, armored horses, who would plow right through the enemy, causing massive blunt force trauma, decapitations, etc. Not the prettiest era ever. But for hundreds of years, the mounted horseman ruled the battlefield. Now horses and armor aren't cheap, nor is fighting on horseback easy, so a new class of warriors developed. Knights gained prestige through combat, and pledged their loyalty to the monarch, or lord, or whomever would toss them the biggest bag of gold. Ethics were attempted through the chivalric code, but that usually went out the window at the first drop of a coin. Knights became landed, because to have plentiful horses, you must have plentiful land. This tied medieval warriors down to one place and allowed for the great tradition of feudalism to begin. Knights were professional soldiers to the extent that their entire lives were essentially lived under arms, or at least, that was the original point. They would eventually become an upper class elite society, who would be shocked to meet the next level of professional soldier…

Swiss Mercenaries and the Landsknechte

By the 1500s, the pike and the crossbow had pretty much relegated knights to a supporting combat role. Monarchs had to protect their horsemen, because knights were doggone expensive and losing one on the battlefield took time and money to replace. In fact, cost was becoming an issue for everyone. The little Ice Age and the Plague had really done a number on Europe’s population. Leaders still wanted to fight each other but weren't sure they had the population to support war and the economy at the same time. Italy and Spain solved this problem by hiring German (Landsknecht) and Swiss mercenaries to fight their wars for them. These guys were good. Well, at war at least.

Landsknechte relied on massive two-handed swords, pikes, and beautiful music to rout their enemies.

While essentially immoral and dissolute (“rape, pillage, and plunder” was a phrase they kinda coined), they excelled on the battlefield. They turned war into their full-time profession. All they did in life was go to war for the man with the biggest pocketbook. And for the monarch, it was usually more than worth it. German and Swiss mercenaries could destroy enemy conscript or volunteer armies more than five times their own size, through superior tactics, technology, firepower, and through sheer bravado. European leaders began to rely on mercenary armies because they appreciated the devastating power that professional soldiers could project. In fact, they began raising their own professional armies. German mercenaries eventually defeated the Swiss, through the use of firearms, and would dominate the merc scene into the 1700s. The idea of German invincibility would last until…

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon burst a lot of bubbles when he came on the scene in 1795. Granted, many pre-existing notions had already been shattered by Revolutionary France’s shocking ideas of warfare. 17th and 18th century to that point warfare had been characterized by small, professional armies. These armies trained hard, fought hard, and were almost universally despised by the people they protected. Standing armies were incredibly expensive and were often viewed as tools of the state. Which they essentially were.

He gets extra style points for the hair.

However, in the 200 years of war between 1580–1780, professional soldiers had almost always been the victors when they went up against militias or levees. This was why almost every single nation-state had developed a moderate to large standing army by 1780. Frederick the Great of Prussia had taken professional soldiering to a whole new level by implementing the general staff system, standard artillery calibers, and professional military education. The small yet mighty Prussian army had smashed the larger French armies over and over during the Seven Years War (1754–1763), leading to an aura of invincibility.

Inspired by American ideals of liberty, equality, and exuberant capitalism, the French people overthrew their government and declared themselves a democracy.

Enter the French Revolution. Inspired by American ideals of liberty, equality, and exuberant capitalism, the French people overthrew their government and declared themselves a democracy. French leaders also noticed how volunteer soldiers in the American Army had managed to stave off the professionals from Britain and Hess (German mercs). They took the idea one step further and created mass conscription, with a twist: a cause to fight for. The French Revolutionary armies won battle after battle against their neighbors, through the use of sheer manpower. Massive 300,000 man French armies would literally overpower the largest army that Austria or Spain could produce, which caused a crisis of faith for other European countries: they could continue to use very expensive professionals (and incur the time and cost it took to replace losses) or they could expose their people to democratic ideals and enlist them into their ranks.

Europe was already reeling from this idea when Napoleon showed up in Italy in 1797 and proceeded to destroy the Austrian armies in detail. His tactics and techniques would be studied and emulated for the next eighteen years, as war became the profession of Europe. He took conscript armies, trained them, instilled pride in them, and then turned them loose against the professionals of Europe (i.e., Prussia) and blew them away. Such was his impact on the profession of arms that he is still studied to this day. Even in…

The U.S. Army

Remember that bit about professional armies being unpopular? Yeah, the new United States hated the thought of a standing army so much that the U.S. Army after the American Revolution consisted of a few hundred troops at West Point and another thousand in the Ohio Country. It was far from a professional organization. America decried the large, professional armies of Europe, blaming them for the constant wars and bankruptcy there. Instead, we would rely on the militia. The idea was that militia units would be called into Federal service if an enemy threatened, negating the need for a large regular Army. The first trial for the militia was the War of 1812. They failed epicly. Apparently, just giving a man a gun and pointing him towards the enemy does not make him a soldier. Also, militia proved reluctant to invade Canada repeatedly, a favorite tactic of the early War Department.