Obligations of the Professional, the Profession, and the Client

It’s been fairly well established elsewhere, and by others in this series, that the military holds itself to be a profession. Given the generally high level of deference most policy makers show military leaders’ judgment and the unparalleled ways in which we allow the military to self-regulate, it seems pretty clear — to me at least — that the American people agree.

What Do We Mean by ‘Ethics’?

The question then, is what ethical responsibilities military members hold as a result of being professionals. Here it’s important to differentiate between morals and ethics. Service members hold both moral and ethical responsibilities, but it’s useful to understand them distinctly, even if they interact within one person. Briefly, what is moral can be understood as ‘that which strengthens the community.’ Humans are inherently social beings, and morality is what allows us to flourish together amid all the frustrations and competing interests of communal life. Conversely, that which is immoral can be understood as ‘that which erodes (undermines, weakens) the community.’

In one sense ethics is the study of morality; it’s the academic discipline many of us learned at school. Its meaning differs when applied to the professions. In this context ethics is understood as that which maintains the standards of the profession. Just like morality ensures human flourishing is possible in community, ethics ensures flourishing is possible in a given profession.

What Do We Mean by ‘Profession’?

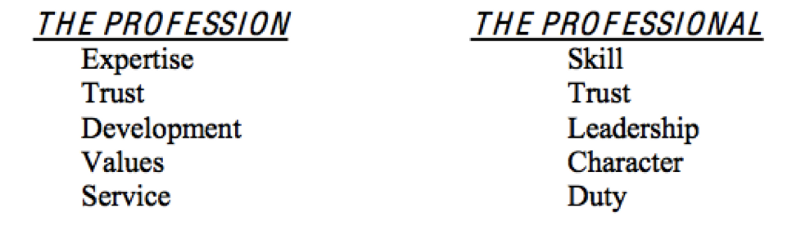

It follows then, that in order to understand the military’s ethical responsibilities, we have to understand the profession’s requirements. The Army tackled this question back in 2010 under General Dempsey’s leadership at TRADOC in The Profession of Arms. They identified five core characteristics of professions, which track with five core traits of professionals.

The Profession of Arms, 2010, 5.

In a nutshell, a profession is characterized by maintaining a high level of specialized expertise. For the military, this expertise is the expert use of violence for a political end; for a doctor it would be the expert use of medicine for health. This expertise is used on behalf of a client, who trusts the professional to use her expertise on his behalf. In the case of the U.S. military, the client whose trust must be maintained is literally the U.S. Constitution, though we most often think of the spirit of the Constitution as embodied by the American people and territory — this is why service members take their oath to support and defend the constitution. As long as trust is maintained, the client allows the professional to build and employ her expertise without a high degree of regulation. The professional is the expert, after all, and knows how best to ply her craft.

Since expertise is perishable and must be maintained, professions also require continuing efforts to develop.

In order to build and maintain expertise, professions put a high premium on development. Not just anyone can join a profession. Only those who demonstrate skill and potential for continued growth are allowed in, and each profession has some semblance of a credentialing process to evaluate that skill and potential (that again, is largely self-regulated without overly invasive input from the client). Boot camp, Officer Candidate School, and Basic School are illustrations in the military context. Law school and the BAR exam are illustrations in the legal context. Since expertise is perishable and must be maintained, professions also require continuing efforts to develop. These can be technical promotion requirements, annual fitness tests and rifle qualifications, and professional military educational requirements.

To ensure the profession remains focused on its client, this development of expertise must be tied to foundational values that benefit the client. Honor, Courage, and Commitment are the Marine Corps’ values that resonate with the American constitution and people. The Hippocratic Oath is an illustration of the values the ground the medical profession. Without these values, the professional may be tempted to prioritize expertise over the client and undertake all sorts of ‘expert’ actions that harm the client more than they help. The final piece of glue that binds a profession to its client is the characteristic of service. Businesses exist to provide profit. Bureaucracies exist to provide efficiency. Professions exist to provide service to the client. When they stop doing this and rather focus on serving themselves or chasing profit, they cease to be a profession.

The Military’s Ethical Responsibilities

So then, if those are the requirements of professions generally, and the profession of arms specifically, what must service members do to maintain the standards of the profession? What ethical responsibilities do service members hold?

I’ll offer five. It’s not my intent to evaluate how well the services are doing in meeting each of these ethical requirements, but anyone who works around the military will see pretty quickly that the services are stronger in some areas than others.

Innovation — tactical, doctrinal, and strategic — is essential to maintaining and developing expertise in a complex, rapidly changing environment.

1. Service members have an ethical responsibility to maintain and develop their expertise. This applies not only to the individual service member, but also to the profession as a whole. Innovation — tactical, doctrinal, and strategic — is essential to maintaining and developing expertise in a complex, rapidly changing environment. Mike Denny is right when he notes that #Professionals Know When to Break the Rules. Why? Because expertise requires judgment, and sometimes that judgment tells the professional that the textbook answer won’t work in a particular set of circumstances. The professional accepts the consequences of bucking doctrine, tradition, or culture, and contributes to the profession as a whole by doing what his expertise tells him is right

…the American people have lost confidence in the services’ ability to prevent and punish sexual assaults on their own.

2. Service members have an ethical responsibility to maintain trust with the American people. One might immediately jump to Abu Ghraib, the desecration of corpses, or other battlefield crimes to illustrate this point, but arguably the services’ seemingly lackadaisical attempts to eliminate sexual assault in the ranks is more telling. Congress was willing to allow the UCMJ to adjudicate potential breaches of combat ethics and the law of armed conflict; however, it is considering removing UCMJ authority from commanders in sexual assault cases. While this likely won’t happen, the 2015 NDAA calls for removing the statute of limitations on sexual assault prosecutions as well as a mandatory dishonorable discharge for certain sex offense convictions. Why? Because the American people have lost confidence in the services’ ability to prevent and punish sexual assaults on their own. Trust, once lost, takes time to rebuild. It is every military professional’s responsibility to not lose that trust in the first place and repair it where necessary. That is, unless the profession doesn’t mind losing the significant latitude it currently holds to regulate itself.

Leaders have the responsibility to provide the necessary top cover for subordinates to practice, fail, and grow.

3. Service members have an ethical responsibility to develop those junior to them. Of all the requirements of the profession, this is the one my students tell me is most routinely ignored. Monitors will talk to service members about the importance of broadening opportunities and key developmental assignments, but the last 13+ years of war have bred some leaders to focus on execution of tasks at the expense of cultivating subordinates’ skill and judgment. Leaders must fight this temptation along with the tendency to micro-manage and crush failure (failure being an essential element of innovating in response to an increasingly complex environment and enemy). Micro-managing and the zero defect mentality make perfect sense for an individual in the short term, but they are disastrous to the profession over time. Leaders have the responsibility to provide the necessary top cover for subordinates to practice, fail, and grow. Subordinates have the responsibility to show initiative and sometimes fail in order to grow.

4. Service members have an ethical responsibility to uphold American values while leveraging their expertise. There’s been a lot of talk lately about the civil-military divide. While Fallows was perhaps less groundbreaking than some may claim, he highlights the challenge of upholding a nation’s values when the natural ties that would transmit those values have weakened. While it is easy (and fair) to blame Americans for failing in their civic responsibility to know about the wars their country wages on their behalf, it is the professional’s responsibility to consistently ‘go back to the well’ to ensure his decisions and actions resonate with the nation he serves. In those moments when what is ‘right’ contradicts what is tactically effective, efficient, or practical, the professional must search for a way to leverage his expertise in the lethal use of force in a manner that upholds American values. If he ignores American values in the pursuit of lethality, he may be a very effective killer, but he is not a professional.

5. Service members have an ethical obligation to serve. This seems obvious, but the current uproar over retirement, education, and medical benefits highlights that segments of our military place a monetary value on their time in uniform. To be absolutely clear — I fully support service members receiving the benefits they were promised when they entered service. This is part of the nation maintaining the military’s trust in us. Still, a profession exists to serve someone other than the professionals. Leaders who recognize and value that in their units and subordinates do better by the profession as a whole than those who do not.

I often struggle with writing about issues of military ethics because statements like the five ethical requirements listed above seem so obvious. At the same time, having taught hundreds of field grade officers over the past six years I know they struggle with meeting these ethical obligations to their subordinates and the nation. This is not because they lack motivation or ability, but because the institutions of the profession at times make it difficult — if not impossible — to do so. While this series of posts examines the obligations of the military professional, it is equally important to examine the obligations of the profession to its members and of the client to those who have chosen to serve on its behalf.

This post was provided by Dr. Rebecca Johnson, an Associate Professor of National Security Affairs at Marine Corps University’s Command and Staff College. Previously, she taught as a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Georgetown Public Policy Institute at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. She completed a Masters in Divinity at Wesley Theological Seminary with concentrations in ethics and world religions in 2010. This article was the basis for her chapter in Redefining the Modern Military: The Intersection of Profession and Ethics. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the DoD, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.