A watershed moment in the history of modern warfare

The Battle of Gallipoli was a watershed moment in the history of warfare. Few other battles were initiated with such high strategic hopes that were then dashed so quickly. Its influence carried far beyond the war in which it occurred. Simultaneously, it spurred some observers to proclaim that the amphibious assault was impossible and others, notably then-Captain Earl “Pete” Ellis of the United States Marine Corps, to completely reexamine the amphibious assault in a modern context and design modern forces to accomplish it. Even in defeat, the battle was a defining moment for Australia and New Zealand whose sons exhibited superhuman courage and endurance in horrific conditions and against desperate odds. Sir Winston Churchill, whose strategic vision was the impetus behind the attempt, faced political exile once the effort failed. He has been both criticized and praised for it since. Questions remain as to whether or not the effort could have succeeded. These questions will continue because at more than one point in the campaign either side could have won. In the end, the campaign was a stalemate through and through. The Allies could not achieve their objectives but neither could the Turks push them back into the sea. Like so many events in military history, inspired leadership at bayonet range can change the plans of nations.

Strategic Environment and Rationale

On January 2nd, 1915, the British government received a call for help. Russia was on the ropes. After dramatic and devastating defeats at the hands of Germany, the Tzarist behemoth was already tottering. Despite its size, Russia could not supply its depleted and defeated armies enough to ensure the defeat of a renewed German offensive the next year. If logistical support from Western Europe could not make it through the Turkish blockade of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorous, Russia may have to seek a separate peace. The commander-in-chief of the reeling Russian armies, Grand Duke Nicholas, first cousin of the Emperor Nicholas II, wanted some kind of effort against the Ottoman Empire to draw off their troops in the Caucasus. The British and the French had more than enough problems of their own, however. The Western Front had just settled into a morass of mud, steel, and blood. The worldwide shock of the massive casualties of the First Battle of the Marne had yet to wear off and the “Race to the Sea” had ended without a winner. Both sides were now locked into a continuous line of entrenchments for 350 miles across Europe. Opening a new front seemed beyond the pale.

Except that it was not. The Dardanelles, instantly recognized by Lord Kitchener as simultaneously the most practicable place to strike as well as the point where the most potential strategic effects could be gained, was weakly defended. Seizing or forcing the Strait and taking Constantinople could have drastically changed the war.

When the Turks had stopped the transit 350,000 tons of shipping had been bottled up in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Turkish blockade had a profound effect on the Entente’s ability to communicate with Russia. Fully 90% of Russia’s grain and 50% of all exports sailed through the Dardanelles to reach the West. When the Turks had stopped the transit 350,000 tons of shipping had been bottled up in the Mediterranean Sea. The Western Allies needed grain from Russia and Russia needed ammunition and other military supplies. The only other way to ship supplies from Western Europe to Russia was to cross the Atlantic, sail through the newly-opened Panama Canal to the Pacific Ocean, then northwest to Vladivostok. There, supplies would have to be unloaded and then moved over the harsh Siberian landscape to western Russia. The Trans-Siberian Railway, then under construction, was not completed until 1916. Russia’s inability to rapidly push supplies and troops across the vast steppes was a key component of its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War ten years earlier.

Allied troops lining the shore at “ANZAC Cove” on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The cove was named after the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) troops that were part of the Allied forces. The Dardanelles Campaign against the Turks was a bloody defeat for the Allies.

The first strategic aim of the campaign was to restore the line of communication with Russia via the Dardanelles and hopefully keep the Eastern Front active. Additionally, the Ottoman Empire was allied with Germany and Turkish armies were fighting Russian troops. Once the Straits were open, Constantinople was a relatively easy target situated on the European coast on the north coast of the Sea of Marmara. The possibility of a collapse of the Ottoman government was not unrealistic. The Empire was run by the “Young Turks” who had deposed the Shah in 1909. Since then, their promises of democracy and liberalization of Turkish society had become subsumed in the day-to-day operations of administering a large but crumbling empire. Regime change or complete collapse in Constantinople seemed forthcoming and it did indeed occur in 1918.

Ways

The War Council thus rightly judged the fragility of Ottoman rule and the ability of military force to contribute to its fall, thus achieving the goal of supporting Russia. There was only one way to use that force, though, and that was to utilize the maritime power of the British to seize the Dardanelles and strike Constantinople.

In 1807, Royal Navy Admiral Duckworth ran the very same straights, past some of the same forts, and was only stopped short of Constantinople herself by lack of wind. With the advent of steam powered ships, that old enemy would no longer be a factor and the Royal Navy thought that the time was ripe to one-up Duckworth’s exploit.

The biggest problems would be the mines that the Turks had placed in the Strait.

There were three ways that the Allies could employ to gain control of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorous. One method was to send a fleet to force the Strait and then, presumably, bombard Constantinople itself from long range. While forts lined the Strait, most were old. One dated to Byzantium. The guns were also of older design and poorly supplied with outdated ammunition. Unfortunately, a unilateral and random bombardment of the old forts ordered by Churchill in November 1914 induced the Turks and their German allies to upgrade some of the guns and increase the amount of mines. The total number of guns was around 100, but still only twelve were modern. Although the Royal Navy ships could outrange these forts, they could still cause casualties and, importantly, interfere with mine clearing operations. The biggest problems would be the mines that the Turks had placed in the Strait. All of this was known to the Admiralty. But their biggest advantage, paradoxically, was the possession of outdated battleships. The Royal Navy had ships, some scheduled for scuttling, that were simply too outdated to face German battleships elsewhere. They were, however, more than effective enough to take on ancient forts and the Admiralty was willing to sacrifice them. One wonders if the sailors of said vessels were quite so enthusiastic.

Another option was to land troops on the weakly defended Gallipoli Peninsula, secure the coast of the Strait, then march overland to Constantinople. This was also an attractive option. The Turkish soldier had a poor reputation amongst the professional armies of Europe and it was thought, even if the Peninsula was defended, their efforts would be desultory at best. As it was, Gallipoli was lightly defended and the Ottoman armies were committed elsewhere, either in the Caucasus or garrisoning their still vast empire. The War Council also considered inducing Greece to provide the troops, but diplomatic efforts to this end were ineffective.

The third option was to do both: seize the Straits and the Peninsula. These attacks would mutually reinforce each other: land forces seize and hold the forts while minesweepers clear the Straits, then Royal Navy ships fire in support of the troops as they approach Constantinople. Admiral Fisher, First Sea Lord, immediately seized upon this option but stressed that it must be simultaneous and it must be done as soon as possible.

The War Council, however, did not grasp this key point as well as had Admiral Fisher. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, was the strongest supporter of any scheme involving Gallipoli. Lord Kitchener, hero of Omdurman and now the Secretary of State for War, initially refused to provide troops, reserving them for the Western Front. Opposition to Fisher’s plan, especially amongst generals on the Western Front who wanted every man available for the trenches, led to a half-way compromise.

Means

The halfway compromise was this: the Navy would try its hand at forcing the Strait and, if unsuccessful, then troops would be provided for an overland campaign. There were concerns that a naval attempt would alert the Ottomans to the danger but Churchill was so supremely confident in the fleets ability to force the Strait that these concerns were apparently shunted aside. This compromise turned Admiral Fisher against the enterprise, but by this point he was the sole dissenting voice. After considering resignation, he instead supported the decision of the Prime Minister.

To force the Strait, an Allied naval task force was formed. The core of this task force were the battleships. Fourteen were provided by the British. These included two semi-dreadnoughts, the Lord Nelson and the Agamemnon. The jewel of the fleet was the brand new super-dreadnought the Queen Elizabeth, sporting 15-inch guns. The French contributed the Bouvet, the Charlemagne, the Suffren, and the Gaulois. The HMS Ark Royal was also in the Mediterranean assigned to support the attack with its sea planes for reconnaissance. The Dardanelles Fleet also included minesweepers, cruisers, and other smaller craft.

Geography

The passage that this task force was intended to force began with the Dardanelles. This strait is 30 miles long and, at one point, is less than a mile wide. The Gallipoli Penninsula forms the western side of the strait. The Dardanelles leads to the Sea of Marmara and then to the Bosphorous, another strait upon which Constantinople is situated on its western shore.

Execution

The first naval attack occurred on February 19th, 1915 when the ships exchanged fire with the Turkish forts. Poor weather caused a full attack to be delayed until February 25th. Initially, the attack went well. Turkish gunners fled from the heavier bombardment from the battleships. Small units of British soldiers and Marines were landed on both sides of the strait and encountered only light resistance except one fort on the Asiatic side whose defenders inflicted heavy casualties on Royal Marines before capitulating.

The Turkish gunners, however, soon returned and resumed firing as the Allied troops abandoned the forts. The small minesweepers, manned by civilians, fled from the harassing fire despite not being hit. The task force again withdrew to regroup. Another full attack was planned for March 18th. By then, the Turkish forts seem to have found their range. Minesweepers cleared the first line of mines, but again the small ships fled once under fire of the forts. In this attack, the Bouvet, the Irresistable, and the Ocean were sunk. The Inflexible, the Suffren, and the Galois were damaged enough that they were out of action. The Albion, the Agamemnon, the Lord Nelson, and the Charlamagne were heavily damaged.

Agamemnon took part in all bombardments of Turkish fortresses in Dardanelles in spring 1916 and was struck by more than 50 projectiles, including 14'' stone shot.

The naval commander, Admiral de Robeck, at first wanted to renew the attack but by March 22nd, the decision had been made by the Kitchener to send the troops required for a land campaign. The naval task force turned to await the arrival of the troops.

When news of the British attack reached Constantinople, the Turkish populace panicked.

Had the troops been present, this would have been the perfect time for the Allies to succeed. The naval attack had induced panic in the Turkish army and their German allies, who sent urgent requests for reinforcements of any kind. No counterattack was ever executed against the landing parties that were sent ashore. When news of the British attack reached Constantinople, the Turkish populace panicked. Government officials made plans to flee the capital. The naval attack had come on the heels of an abortive Turkish invasion of Russia which ended with massive Turkish casualties at the Battle of Sarikamish on 4 January 1915. The German embassy expected the Turks to sue for peace and burned their records in expectation of fleeing the city. Even a few shells lobbed into the city might have caused a complete collapse. The only ones that expected the allied attack to fail were the allies themselves. The Turkish government was so panicked that they entirely turned over the defense of the Dardanelles to the ranking German advisor, General Liman von Sanders. Sanders knew that an amphibious attack was coming and, looking over the panicked Turkish defenses, said: “If the English only leave me alone for eight days!”

The allies gave him four weeks. Although the War Council had planned to send troops if they naval attack did not succeed, very few preparations had actually been made. A commander, General Sir Ian Hamilton, had been designated and dispatched to the Mediterranean. He was actually present to observe the final naval attacks. But as yet he had no staff and had not even met the troops he would lead.

The five beaches were known to be good landing places but the terrain inland was largely a mystery to Hamilton’s staff, despite previous air reconnaissance.

The plan for the nascent expeditionary force was to form itself in Egypt around the British 29th Division. It would also include the Royal Naval Division, hastily formed from Royal Navy and Royal Marine reservists at the outbreak of the war. Although a new unit, they had already seen combat in Europe. The 1st Australian Division and the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) were also assigned. Lastly, the French provided the division strength Corps expeditionnaire d’Orient. A landing on the Asiatic side of the Dardanelles was considered but then forbidden by Kitchener, limiting Hamilton to a main landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula and only diversionary attacks on the eastern side. Hamilton also considered a landing on the narrowest portion of the peninsula but this was rejected since the Turks were there in force.

French troops of the Corps expeditionnaire d’Orient landing on Lemnos, 1915, prior to the Gallipoli Campaign.

In the end, Hamilton settled on landing where the Turks were not: the southern tip of the peninsula. Five beaches were selected, Y, X, W, V, and S with a diversionary attack at Kum Kale on the western side conducted by the French and the landing ANZAC landing on the left flank up the coast. The five beaches were known to be good landing places but the terrain inland was largely a mystery to Hamilton’s staff, despite previous air reconnaissance. From the beaches, the allies would roll back the Turkish defenders and march to Constantinople. Mathematically, this had a reasonable chance to succeed. General von Sanders had six Turkish divisions at his disposal, amounting to about 84,000 men, but they had 150 miles of coastline to defend. Hamilton, with one less division, could concentrate his forces where and when he pleased. Landing at multiple beaches was a good idea. If one beach was defended, another might not be and forces could be shifted from one to the other. This would also confuse the Turks as to where the British main effort had landed. Once ashore, the allied troops were to seize high ground inland while the force consolidated on land.

The forces that would execute this plan however, were in disarray. First Hamilton inspected the planned intermediate staging base at Mudros harbor, on the island of Lemnos. There was no fresh water to be had and the harbor had no piers or shelter of any kind. Troops already staged there were randomly distributed amongst the transports according to no plan. Troops not only lacked unit integrity, but supplies were randomly distributed as well. Guns and ammunition, even wagons and horses, were in separate transports. To fix this, Hamilton had to order the naval transports to Alexandria, where more troops were staged, to completely unload and then reload the embarked troops and supplies. There was also little heed given to operational security. In Alexandria and again in Cairo, Hamilton ordered a public parade of the troops. Letters sent to the troops from home were addressed to the “Constantinople Field Force.” If there was any mystery at all to Allied intentions, it was quickly squandered.

On 23 April the troop transports sailed from Mudros harbor and took staging positions along with the fleet off the Gallipoli Peninsula. The troops were provided with a final hot meal and gear was checked one last time. The troops had their rifles and 200 rounds of ammunition, shovels, and three days of rations; a paltry allotment for the impending eight month campaign.

At 0500 on 25 April the naval bombardment began and troops began landing simultaneously at each of the beaches. The assault troops were transported in small row boats tethered one behind the other and pulled from the front by a small steamer. The steamers were commanded by junior naval officers, two of whom were 13-year old Royal Naval College cadets. Depending on the beach, it was a day of either good luck or bad as beaches were either heavily defended or practically undefended. At ANZAC cove, the landing occurred accidentally one mile north of the planned beach. The Australians and New Zealanders splashed through the water and hit a beach surrounded on all sides by high, tortuous ground arranged in an amphitheater where the killing ground of the stage was occupied by the troops. The landing was immediately opposed. Cracks of rifle fire broke out from the surrounding high ground, and a unit of Turks formed on the beach to charge, only to be driven off by Australian bayonets. Still, the Turkish defense was disjointed. Some ANZAC units pushed inland over a mile before coming into contact with outposts, but other Turkish positions confronted the allies on the beach itself. A concerted ANZAC effort to take the hills could have swept them away, but the confusion of landing in the wrong place prevented the officers from gaining control. Some units did nothing, others aggressively chased the Turks inland but then became lost in the craggy hills.

A photo taken from the deck of the River Clyde looking towards the shore of V beach. There are dead and wounded men in the lighter.

At W and V beaches on either side of the southernmost point of the peninsula, British troops enjoyed no such luck. Although only two companies of Turkish troops were assigned to the portion of coastline that comprised W and V, their machine guns were perfectly sighted to fire upon the troops before they could even exit the transports. W and V beaches were the only ones that had been fortified by the Turks.

The landing at V beach involved the SS River Clyde, a coal ship converted into a troop transport intended to beached and then to disgorge its troops like an amphibious Trojan Horse. The ruse did not succeed and Turkish machineguns kept 1,000 British troops bottled up in the ship until nightfall. At W beach, entire transports were landed with every allied troop aboard already killed or wounded by Turkish fire.

“… the sea behind was absolutely crimson, and you could hear the groans through the rattle of musketry. A few were firing. I signaled to them to advance… I then perceived they were all hit.” Major Shaw, Lancashire Fusiliers.

At Y, X, and S, no substantial Turkish opposition was forthcoming. The French forces landing at Kum Kale were also unopposed and seized a Byzantine-era fort- the same fort taken at great cost by the Royal Marines in the spring- when the defenders surrendered without firing a shot.

The Turkish commanders were in a panic and their German commander was completely addled as to where the battle was even taking place.

On the Turkish side, General von Sanders was notified immediately of the landings but just as immediately realized that his dispositions were less than ideal. His forces were stationed at Bulair, fully forty miles to the north of the landings. These forces were under fire by the Allied fleet in an effective use of firepower to distract and confuse the Turkish forces. Sanders believed that this fire presaged a main landing at Bulair and ordered the Turkish Seventh Division to march north- away from the actual landings- to reinforce his position at Bulair.

It was at this point that the allies were again given a golden opportunity. The Turkish commanders were in a panic and their German commander was completely addled as to where the battle was even taking place. Only two of the landings were being disputed and troops at the other locations had complete freedom of action to attack the Turks on their terms. The most difficult part of an amphibious assault- getting off the beach- was all but accomplished.

So much planning had gone into the landings that, once the landings were accomplished, subordinate commanders had no direction.

But then the allies stopped. At S Beach, a British battalion was confronted by an overstretched Turkish platoon. But their orders were to get ashore and wait. And so they did. The British commander in charge of Y Beach, where there were no defenders at all, was told to wait for orders to push on. He received no communication of any kind from his higher headquarters for 29 full hours after landing. During this lull, Hamilton remained afloat having chosen not to make the landing at any one place to preserve his situational awareness. This may make sense today with modern communications systems, but in 1915 it rendered Hamilton unable to affect the situation. So much planning had gone into the landings that, once the landings were accomplished, subordinate commanders had no direction. The 29th Division official history states:

“But, in contrast to the gallant exploits of the morning a certain inertia seems to have overtaken the troops on this part of the front, who now amounted to at least 2,000 men… Faced with a definite task- the capture of the beaches- the 29th Division had put an indelible mark on history. But once that task was done, platoon, company, and even battalion commanders, each in their own sphere, were awaiting fresh and definite orders, and on their own initiative did little to exploit the morning’s success or to keep in touch with the enemy.”

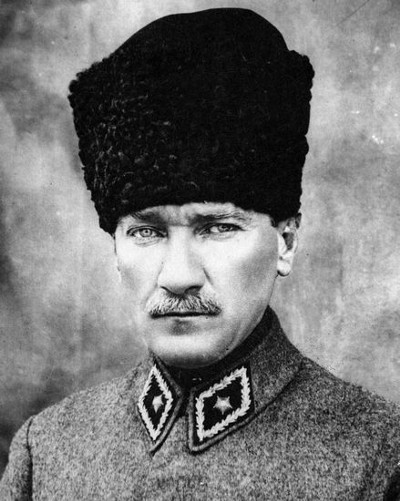

Mustafa Kemal Pasa

It was at this point, where the plans of both sides had gone awry that the battle could go in either direction and it was on the spot leadership that made the difference. The commander of the Turkish 19th Division, held in reserve, was 34 years old and had thus far had an undistinguished career but the future Father of Modern Turkey stepped into the breach. Mustafa Kemal had received orders to send one battalion to confront the ANZAC troops, and this he had done personally. He reached the cove far ahead of his own battalion and was confronted by retreating Turks from other units who had expended their ammunition. He turned them around and ordered them to fix bayonets, which apparently stopped an Australian effort at the heights. Kemal held the heights until his battalion reached it and then called for two more regiments from his division. On his own authority, Mustafa Kemal had committed General von Sanders’ reserve force at exactly the right place and time, preventing the Allies from outflanking the southern Turkish defenses then battering W and V beaches. He only contacted his higher headquarters to ask permission to commit his remaining regiment.

By May 4th, Kemal had failed to defeat the ANZACs, but he had bottled them up in the cove and broken the momentum of the allied campaign.

With these forces, Kemal launched numerous and furious attacks on the ANZAC position, attempting to push attacking troops into the sea. The fact that this did not happen is testament to the courage and skill of the ANZACs, rightfully legendary even today. Attack and counterattack ensued, frequently at bayonet range, amongst the rocks and pits around the cove. By May 4th, Kemal had failed to defeat the ANZACs, but he had bottled them up in the cove and broken the momentum of the allied campaign. Further allied offensives along the line continued until May 6th, but once the spell of surprise had been broken by Kemal’s aggressive initiative, the allied attack stalled. The Turks converted hasty defenses into deep entrenchments all around the landing sites, still disjointed and unable to support each other.

Though both sides continued to launch attacks at each other’s entrenchments, the Gallipoli Peninsula was now gripped in exactly the kind of stalemate that had occurred on the Western Front. Their backs to the sea, the allies could not generate enough combat power to succeed at frontal assaults and their ability to maneuver was now nil. The Turks were in much the same situation. They had taken massive casualties in the process of stopping the allies and none were forthcoming from the weak Turkish government.

Australian troops in a Gallipoli trench.

The stalemate lasted until August. The allied troops, cramped on the beaches, were subjected to constant sniper and artillery fire, plus occasional Turkish attacks. At points, “no man’s land” between the trenches of both sides was only ten meters wide. This and the extremely shallow beachheads led to a feeling of claustrophobia. There was literally nowhere for the Allied troops to go to break the tension of direct confrontation with the enemy. Turkish artillery, while inaccurate, could strike any point at any time. Callous “barracks humor” became the norm. Supplies of food were monotonous and bland, provision of fresh water inconsistent. Typhoid and dysentery wracked the troops of both sides, but especially the Allied troops. The ability to bathe in the water was the only form of recreation, but even that could be interrupted by artillery fire. The most famous of the British colonial troops were of course the Australians and New Zealanders of the ANZAC Corps but other Commonwealth and Dominion troops fought in the battle as well, including Irish troops, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment from Canada, Indians, Nepalese Ghurkas, and a battalion of Jewish volunteers. The French contingent included elements of the Foreign Legion and Colonial Senegalese troops. Turkish units included not just ethnic Turks but Arab troops as well.

Most of the high-ranking officers were veterans of the Western Front, the troops had yet to see combat.

To break this deadlock, the War Council agreed to a proposal by Hamilton to launch a new amphibious assault to the rear of the Turkish positions, now situated around the southern-most portion of the peninsula around the allied positions. At Suvla Bay, further up the western coast from ANZAC cove, there were no Turkish positions or entrenchments at all. A strong enough landing would turn the Turkish line unless they could pivot enough forces north to meet it. The British committed eight divisions to this effort, although three were “Kitchener’s New Army” divisions, freshly-formed and hastily trained. Most of the high-ranking officers were veterans of the Western Front, the troops had yet to see combat.

The fresh British troops landed on 6 August, 1915. The landing was timed to coincide with attempts to break out of the southern beaches all across the line that had begun the day before, keeping the Turks occupied. The outline of this plan was apparently predicted by Mustafa Kemal, still a division commander, but he was ignored. In the event, only 1,500 Turkish soldiers were posted near Suvla Bay- three miles inland- to stop a British landing force of 20,000.

The landing began at 2130 on the night of August 6th and the troops landed in darkness. Two small Turkish outposts observed the landing, took potshots at the new arrivals, then retreated in accordance with their orders. All 20,000 troops had made it ashore, but in the darkness and unfamiliar terrain, many units got lost or simply paused to rest. By 0430 on the 7th, the assault had bogged down without meeting any substantial resistance. Turkish artillery was firing at the ships off shore, but the fire was inaccurate and ineffective. Further confusion was caused by the maps given to the new troops: landmarks were labelled by their Turkish names but the written orders for each unit had used English names. The high-ground inland from the landings was supposed to have been seized by dawn, but the new troops spent an extremely hot day waiting on the beaches while orders and counter-orders were disentangled.

Soldiers dug in at Chocolate Hill, Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, 1915.

At dusk they began to advance and took two objectives, Chocolate Hill and Green Hill, while Turkish troops retreated without resisting. But the British division commanders had not gone forward with the troops and instead remained on the beach. Hamilton, who had cut himself off from the first landings by remaining aboard ship, this time had done so by remaining on an offshore island before sailing to the Gallipoli coast. He might as well have been in London. The advancing troops had to wait for new orders once an objective was taken. The local commander of the Turkish force of 1,500 troops begged General von Sanders, again misled as to where the main attack was occurring, for reinforcements.

Three days into the renewed battle and neither side had achieved a major objective.

Here again the British troops stopped. On August 8th, just short of their objectives and still having met only light resistance, the British commanders decided to stop, entrench, and issue congratulatory remarks to the troops. Orders from Hamilton to seize the high ground of Tekke Tepe, still unoccupied by the Turks, went ignored by the division commanders ensconced on the beaches. On the evening of the 8th, Hamilton had to go ashore himself and directly order the front line troops to advance, bypassing the chain of command. The southern breakout attacks had also stalled, although at least the attacks occurred. For his part, Sanders had much the same problem. Now alerted to the landing at Suvla Bay, he ordered immediate Turkish attacks. Turkish corps commanders, like their British counterparts, delayed and obfuscated to avoid doing so. Reinforcements that had been ordered down from Bulair had never left or had been delayed. Three days into the renewed battle and neither side had achieved a major objective. Hamilton could not attack, and Sanders could not counterattack.

Again, the battle teetered on the edge where inspired leadership could tip the scales for either combatant. This time, however, General von Sanders knew it. On the evening of August 8th, he fired everyone in the chain of command below him and above Mustafa Kemal, and put Kemal in charge of the entire defense.

Kemal’s 19th Division had met the renewed offensive at ANZAC Cove and had been hard pressed doing so. Kemal himself had been awake for two days personally directing the defense. The division doctor had been drugging him to keep him going. When he was notified that he was now the commander of all Turkish forces on the peninsula, he immediately began issuing orders. He rode to the Turkish position at Suvla Bay and ordered an immediate attack in force. The new British troops, prodded finally into action by Hamilton, had finally begun advancing at 0330 on 9 August. At 0400, the Turkish attack organized by Mustafa Kemal struck. The result was almost immediate disintegration of the British offensive. By 0600 Hamilton, now back aboard ship, could see the force that he had finally gotten to attack retreating down to the beaches in disarray, running for their lives. Mustafa Kemal, watching the same scene from a mountaintop, now received word that Turkish lines further south were in danger of breaking. He immediately rode south and organized a counteroffensive at Chunuk Bair. Before the assault, Kemal went out into no man’s land and whispered orders and encouragement back to the Turkish line. At 0430 on 10 August, he personally led a bayonet charge two regiments strong against the high ground on Sari Bair, taken by British troops the day before. This attack swept the British troops from the heights and back down onto the beaches.

The Turkish troops were devastated and casualties were high, but in a matter of hours Mustafa Kemal had completely erased the gains made by Hamilton’s renewed offensive and locked the Allied troops back into their tiny sea-side cells. Two more offensives were attempted in August in which the Allied troops acquitted themselves well as usual but against such great odds and without inspired battlefield leadership, the attacks faltered. The stalemate had returned.

The casualties were tragically horrific. The Allies lost 265,000 soldiers and sailors total.

Still, the Allies persisted. In September, a third assault was contemplated. This time on the Asiatic side of the strait by four French divisions. In October, the fleet wanted to try to assault the strait itself again. But by mid-October, the War Council was considering a withdrawal. Then a completely new amphibious assault at Salonika was contemplated. Hamilton was sacked and replaced by another a general transferred from the Western Front, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Monro. Monro believed that the war could only be won on the Western Front and that Gallipoli was a sideshow. He was tasked with evaluating whether or not reinforcements could save the situation but, predictably, he decided on evacuation. Despite estimates that nearly half of the remaining troops would be killed effecting a withdrawal (40,000 casualties) it was decided that the forces would be withdrawn. From 28 December 1915 to 9 January 1916, troop transports slid alongshore at night to take on troops. This was the most well-executed part of the Allied campaign and the Turks did not oppose it. Not even Mustafa Kemal realized that a withdrawal was taking place until it was too late.

The casualties were tragically horrific. The Allies lost 265,000 soldiers and sailors total. The 29th Division lost its strength twice over. Amazingly, 8,566 New Zealanders served in the campaign and accounted for 14,720 casualties. They were wounded twice or even three times but returned to the lines again and again. The courage of the soldiers on both sides is unquestionable.

Conclusion

What is questionable is whether the Allies could have succeeded. British historian John Keegan believed that they could not have and that the plan was doomed from the start. Basil Liddell Hart believed that the plan, better executed, could have succeeded, although in history of World War I he ignores the second landing entirely. On the initial landing, he correctly states: “His [Hamilton] oft-criticized choice of landing place could hardly have been improved upon if, by supernatural power, he had been able to know the enemy’s dispositions. By avoiding the natural line of expectation, the pitfall of commonplace generalship, and by distracting the enemy’s attention to that line, he ensured his own troops an immense superiority of force at the actual landing places- although his total force was less than that of the Turks.” That the opportunity created by the inspired choice of assault was squandered was due in part to Mustafa Kemal but probably more so by the amateur execution of key leaders on the ground. Of course, these were not commanders new to combat but they were new to amphibious operations and had no doctrine at all to guide them.

The initial landings, if conducted by professional amphibious forces familiar with the unique exigencies of expeditionary operations, could have succeeded.

It seems clear that given the weakness of the Ottoman Empire and the poor Turkish and German leadership at every level that was not occupied by Mustafa Kemal that some force could have taken the peninsula, forced the strait, seized Constantinople, and turned the tide of history. But that force was not the Allies. The half-baked plan to dip their toes in with a naval attack and only commit to a land invasion if it failed gave the Turks too much time to prepare. The poor working relationship between the Royal Navy and the Army produced a disjointed effort from the start. The initial landings, if conducted by professional amphibious forces familiar with the unique exigencies of expeditionary operations, could have succeeded. Even the second landing, if conducted by veteran forces, could have turned the tide.

What finally defeated both amphibious landings was the desultory and sluggish leadership of unit leaders actually on the scene.

Despite all this, the Turkish leadership made many mistakes as well. If Mustafa Kemal was the commander of the British 29th Division vice the commander of the Turkish 19th, the battle would have been very different. Winston Churchill may have been right when it came to the strategy, but he could not see that the Allies did not have the means. What finally defeated both amphibious landings was the desultory and sluggish leadership of unit leaders actually on the scene. The legendary bravery and tactical prowess of the troops was not enough to overcome these deficits. For the attack to have succeeded, the Allies would have to have had a military used to joint operations and a professional force familiar with amphibious operations. This they did not have.

Before the age of the machine gun and modern artillery, non-specialized troops lacking any kind of amphibious doctrine may have been able to carry an assault from the sea. But Gallipoli marks the point where they no longer could. Across the Atlantic Ocean, a generation of young officers at Quantico would be tasked with developing just such a doctrine and turning a force of Marines used to guarding US Navy posts into a professional, expeditionary corps.

Captain B. A. Friedman, USMC is a field artillery officer and author of 21st Century Ellis, as well as numerous articles and posts. He is also a founding member of the Military Writers Guild. Views contained in this post do not represent the United States Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.