Today, leaders across the world are seeing the early effects of another transformational technology: widely available large-language models. Viewed as the first step in true artificial general intelligence, large-language models incorporate massive amounts of data from books and articles into training sets that allow them to recognize patterns between words and images. Large-language models will likely have a larger impact on the battlefield than autonomous drones due to their ability to automate the many aspects of staff work that prevent military leaders from focusing on tactics and strategy.

Historical Guideposts: Illuminating the Future of Warfare

A nation’s political and military leaders must objectively seek out and use history's lessons as guideposts, capturing and applying lessons learned from the most repeated, catastrophic missteps of others to remain adaptable to future warfare's most probable scenarios. History matters more in avoiding past catastrophes than predicting specific events years into the future.

Conflict Realism: A New School of Thought for Examining the Future of Armed Conflict

Not formalized in existing literature, four basic schools of thought exist in the conflict and defense studies fields. These camps include the Futurist, Traditionalist, Institutionalist, and Conflict Realism. Each of these camps provides value to the study of armed conflict. Yet, the over-reliance on one camp over others creates unhelpful distortions and implications that can impede the student and practitioner of war’s ability to think clearly about war and warfare. A holistic view of armed conflict, which takes into consideration all four camps, is needed to help overcome unhelpful distortions and find the essence of the problems in armed conflict.

When Predicting the Future, Remember, You’re Probably Wrong

History remains the best guide to predicting the future — but such predictions are still more likely than not to be wrong. Those who postulate and prognosticate on the future of warfare, and those consuming their output, would be well served by keeping this in mind. Such is the nature of predicting the future writ large, and this applies in the realm of warfare.

#Reviewing War Transformed

The character of war is rapidly changing. The increasing availability of evolving technology confounds previous frameworks for military operations. Socioeconomic factors and demographic shifts complicate manpower and force generation models for national defense. Ubiquitous connectivity links individuals to global audiences, expanding the reach of influence activities. And a renewed emphasis on strategic competition enhances the scope of military action below the threshold of violence. This is the world that Mick Ryan explores in War Transformed: The Future of Twenty-First-Century Great Power Competition and Conflict.

#Reviewing Bitskrieg

In Bitskrieg, John Arquilla distills much from his three decades of advocacy about networked warfare into a compact volume accessible to a wide audience. He displays a continuing ability to produce provocative arguments and engaging books. The tenets of Bitskrieg are consistent with many of Arquilla’s previous writings. These include the point that networked warfare or netwar encompasses cyber conflict but extends beyond it.

#Reviewing The Future of War: A History

Warbot Ethics: A Framework for Autonomy and Accountability

While the rapid advance of artificial intelligence and warbots has the potential to disrupt U.S. military force structures and employment methods, they offer great promise and are worth the risk. This is especially true as the conceptual mechanisms for providing variable autonomy and direct accountability are already in place. Commanders will retain their central role in determining the level of variable autonomy given to subordinates, whether human or warbot, and will continue to be held accountable when things inevitably go wrong for either.

The Army Looks to the Future

The Chief of Staff of the Army released the results of a study which was designed to determine how the Army can best achieve “success in battle” in the future. I was able to obtain a copy of this report and want to share it here. The Chief convened a group of the best military brains available because he understands that “wars are still fought on little bits of bloody earth, and they are ended when the enemy’s will to resist is broken, and armed men stand victorious on his home soil.”

Preparing for the #FutureOfWar

While it can be said with some confidence that freedom and democracy practiced by an active and educated citizenry provides a solid foundation for the enduring success of any state, America should be wary of using these ideals as measures of an entity’s immediate threat to its security (depending, of course, on the actions of said entity at any given time) or as a mandate for certain types of action against any entity.

Back to the Future

The Danger of Overconfidence in the #FutureofWar

From Operation Desert Storm to Operation Enduring Freedom, the United States Navy has enjoyed an asymmetric technological advantage over its adversaries.[1] Uncontested command and control dominance allowed American commanders to synchronize efforts across broad theaters and deliver catastrophic effects upon the nation’s enemies. These years of uncontested command and control dominance birthed a generation of commanders who now expect accurate, timely, and actionable information. High levels of situational awareness have become the rule, not the exception. The Navy and its strike groups now stand in danger of becoming victims of their own technological success. An overreliance on highly networked command and control structures has left carrier strike groups unprepared to operate effectively against future near-peer adversaries.

An overreliance on highly networked command and control structures has left carrier strike groups unprepared to operate effectively against future near-peer adversaries.

Data-Links Are Our Achilles’ Heel

Conceptual image shows the inter-relationships between sea, land and air forces in a Network Centric Warfare environment. (via RAAF/BAE Systems Australia)

The concept of Network Centric Warfare (NCW) was birthed from the realization that integrating many of these systems would “create higher [situational] awareness,” for commanders.[2] Forecasting the looming dependence on NCW, the now defunct Office of Force Transformation claimed, “…Forces that are networked together outfight forces that are not.”[3] Merging vast amounts of information together into one common operating picture is the most challenging element in NCW, and tactical data-links serve as the means for accomplishing this task.

The future of strike group warfare is a concept named Naval Integrated Fire Control (NIFC). Recently NIFC was rebranded NIFC-CA, accounting for additional counter air capabilities. NIFC-CA doubles down on data-links, particularly Link-16. A January 2014 United States Naval Institute News article boasted, “Every unit within the carrier strike group — in the air, on the surface, or under water — would be networked through a series of existing and planned data-links so the carrier strike group commander has as clear a picture as possible of the battle-space.”[4] Read Admiral Manazir, Director of Air Warfare added, “We’ll be able to show a common picture to everybody. And now the decision-maker can be in more places than before.” In spite of his enthusiasm for NIFC-CA, Rear Admiral Manazir reveals a serious problem. “We need to have that link capability that the enemy can’t find and then it can’t jam. The links are our Achilles’ heel, and they always have been. And so protection of links is one of our key attributes” (emphasis added). What Rear Admiral Manazir calls a “key attribute,” most professional military education students would instead call a critical vulnerability.

It is unfair to criticize any commander for wanting more of this informational power. But what happens when this information is threatened, degraded, or denied?

Strike group commanders now rely heavily on information shared across data-links, specifically Link-16, to build their situational awareness. This information sharing enables impressive capabilities: rapid decision-making, massing of force, and very quick after-action assessments. It is unfair to criticize any commander for wanting more of this informational power. But what happens when this information is threatened, degraded, or denied? This question is important, because despite ongoing efforts to harden tactical data-links against attack, eliminating the threat is impossible.

Unjustified Overconfidence

Today we know potential adversaries are developing cyber-space and electronic warfare capabilities to neutralize, disrupt and degrade our communications systems. The challenge is in balancing the benefits and advantages derived from using high-tech communications with the vulnerabilities inherent in becoming overly dependent upon them. — Christine Fox, Former Acting Deputy Secretary of Defense.[5]

The message Ms. Fox delivered is clear: we must not allow a fascination with technology to stand in the way of executing basic war-fighting functions. She went on to state that Cold War-era U.S. naval forces planned to lose communication capabilities against the Soviets, then asked what has changed? Why would the Navy not share that concern about other potential adversaries?

At 22:26 GMT, 11 January 2007, China slammed a kill vehicle into one of its dead metrological satellites, proving to the world that they were part of the small but unfortunately growing club of countries that can accomplish the difficult task of hypervelocity interceptions in space. As a signal to the world, this test highlighted both China’s technological prowess and the fact that China will not quietly stand by while the United States tries to expand its influence in the region with new measures such as the US-India nuclear deal. We have analyzed the orbits of the debris from this interception and from that put limits on the properties of the interceptor. We find that not only can China threaten low Earth orbit satellites, but, by mounting the same interceptor on one of its rockets capable of lofting a satellite into geostationary orbit, all of the US communications satellites. (via MIT Science, Technology, and Global Security Working Group)

In 2007 China successfully destroyed a satellite in orbit. In January 2014, the commander of U.S. Air Force Space Command, General William Shelton, stated, “direct attack weapons, like the Chinese anti-satellite system, can destroy our space systems.”[6] He added that the most critical targets are those satellites providing “survivable communications and missile warning.” Clearly, U.S. forces can no longer remain complacent. An enemy attack on Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites would severely affect a strike group’s ability to accomplish the most basic tasks to the most complex.

The portion of the spectrum used for Link-16 communications is the ultra high frequency (UHF) band. UHF communications are line of sight. (via “Understanding Voice and Data Link Networking,” December 2013, Northrup Grumman Public Release 13–2457)

Satellite denial is not the only area for concern. Several nations are now producing aircraft, ground, and naval vessels with advanced electronic attack suites capable of contesting coveted regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. In a complex network of data and sensor sharing, each node is a contributor, and some nodes are more critical than others. In some cases, enemy electronic attack need only attack the right nodes to have debilitating effects across the entire network. China is pursuing broadband jamming and partial band interference of the Link-16 network with that objective in mind.[7] According to Richard Fisher, an expert on China’s military with the International Assessment and Strategy Center, “…taking away Link-16 makes our defensive challenge far more difficult and makes it far more expensive in terms of casualties in any future conflict with China.”[8]

Fortunately, past exercises and experiences serve as a guide for the future.

As Deputy Secretary Fox and General Shelton have pointed out, the threat is real. If we accept that strike group commanders have become overly reliant upon networked command and control structures, and that these networks are vulnerable to attack, then commanders must have a clearer understanding of what operational impacts can be expected. Fortunately, past exercises and experiences serve as a guide for the future.

Back to the Future

“It is widely recognized that a carrier task force cannot provide for its air defense under conditions likely to exist in combat in the Mediterranean.” — Admiral John H. Cassady, Commander-in-Chief U.S. Naval Forces, East Atlantic and Mediterranean, 1956 [9]

Signalman Seaman Adrian Delaney practices his semaphore aboard the amphibious dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD 49) during an at-sea training evolution with the Royal Thai Navy tank landing ship Her Thai Majesty’s Ship (HTMS) Prathong (LST 715) during the Thailand phase of exercise Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT). (U.S. Navy photo by Journalist 3rd Class Alicia T. Boatwright)

In 1956, Vice Admiral Cassady recognized that the U.S. Navy’s hope for unchallenged access to operationally significant waters was in jeopardy. A series of exercises, under the name HAYSTACK, demonstrated how effectively Soviet forces could use electronic emissions and direction finding equipment to find and fix American aircraft carriers. As a result, HAYSTACK gave rise to emission control. Initially, strike groups operating under strict emission control conditions struggled to command and control dispersed forces throughout their areas of responsibility.

Faced with greatly diminished electronic command and control capabilities [10], commanders developed creative and exceedingly “low tech” solutions. American sailors relearned the art of semaphore and visual Morse code. Helicopters developed methods for airdropping buoys containing written messages alongside friendly vessels.[11]

For the remainder of the Cold War, carrier strike groups routinely practiced emission control operations, and commanders took considerable pride in their ability to make an aircraft carrier seemingly disappear. In 1986, the RANGER participated in the multinational RIMPAC exercise. Despite the opposing forces’ best efforts to locate it, RANGER went undetected for nearly fourteen days while in transit from California to Hawaii.[12] Making this all the more impressive was the fact that RANGER continued flight operations during the transit.

The similarities between preemptive emission control and anticipated command and control warfare environments are undeniable.

Emission control training continued through the 20th century, though with less sense of urgency after the fall of the Soviet Union. Today, carrier strike groups may practice emission control operations once or twice during a work-up cycle. These events are often heavily scripted and rarely involve night flight operations. Carrier air wings undergoing graduate level training at the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center only recently began training in a limited GPS and Link-16 degraded environment. Anecdotal feedback from pilots who have participated in these events alludes to significant challenges.[13]

The similarities between preemptive emission control and anticipated command and control warfare environments are undeniable. With small modifications HAYSTACK provides strike group commanders with a solid starting point if they wish to better prepare their sailors for future wars.

Recommendations and Conclusion

“Confidence is contagious; so is overconfidence….” — Vince Lombardi

We must not assume that future conflicts will be fought against adversaries who are incapable of challenging American technological advantages. China has demonstrated the ability to destroy satellites in orbit, and they are actively pursuing electronic attack capabilities to neutralize Link-16. These facts must be understood and accepted by commanders who have dismissed the concept of command by negation while at the same time failing to demand realistic training.

Effective command by negation demands a lucid expression of commander’s intent. Commander’s intent should focus on macro level issues and answer two questions: What is the desired end state? What will success look like?[14] Commander’s intent should not try to answer specific questions of weapons employment and target selection. Subordinates should be empowered and encouraged to use individual initiative towards achieving the stated objective. If strike group commanders and their staffs can relearn the art of operational design, and focus those efforts towards developing effective statements of intent, their forces stand a greater chance of success in a world without Predator feeds, Link-16, satellite communications, Internet Relay Chat, and e-mail. Failure to pursue this goal will only serve to maintain the status quo, which is to say deploying forces will remain unprepared to counter command and control warfare.

If the U.S. believes it remains the preeminent military force in the world, then why wouldn’t its forces train against realistic command and control warfare capabilities, assuming the implied result would be increased competence?

Quartermaster 3rd Class Alex Davis lowers a signal flag aboard the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73) during a flag hoist exercise on the ship’s signal bridge. George Washington, the Navy’s only permanently forward deployed aircraft carrier, is underway supporting security and stability in the western Pacific Ocean. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Apprentice Marcos Vazquez)

Additionally, strike group commanders must demand realistic training that mimics a command and control warfare environment. It is not enough to conduct emission control exercises once or twice during pre-deployment training. Afloat training groups should own this training requirement and place greater emphasis on it during strike group training in their Composite Training Unit Exercise and Joint Task Force Exercise.[15] The Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center should consider increasing the frequency and complexity of the degraded environment training it provides to carrier air wings. Individual units must be encouraged to conduct local training sorties without the aid of data-links and secure communications.[16] Focusing on our own capabilities and how we intend to counter command and control warfare will add a layer of complexity, and therefore value, to these training exercises. If the U.S. believes it remains the preeminent military force in the world, then why wouldn’t its forces train against realistic command and control warfare capabilities, assuming the implied result would be increased competence? Ultimately, the units charged with preparing strike groups for deployment will respond to demands from operational commanders. If strike group commanders recognize their unpreparedness and demand a solution, time, money, and resources will be allocated appropriately.

While much of the #FutureOfWar discussion has centered on technological developments and innovation, we should consider whether or not this infatuation has led us down a dangerous path. Have we become so enthralled and dependent upon what is undeniably a critical vulnerability to the extent of rendering us ineffective in its absence? This is an important question to ask because, arguably, the winner of future wars will not simply be the side with the most advanced weapon systems, but likely the side who can deftly shift “back in time.”

Jack Curtis is a graduate of the University of Florida and the Naval War College. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] “Our technological advantage is a key to America’s military dominance.” President Barack Obama, May 2009.

[2] Network-Centric Warfare — Its Origins and Future. Cebrowski and Gartska, 1998.

[3] The Implementation of Network-Centric Warfare Brochure. 2005.

[4] “Inside the Navy’s Next Air War.” USNI News. Majumdar and LaGrone, January 2014.

[5] Transcript of speech delivered April 7, 2014.

[6] “General: Strategic Military Satellites Vulnerable to Attack in Future Space War.” The Washington Free Beacon. Bill Gertz. 2014.

[7] Chinese Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation publication, quoted in Gertz.

[8] Fisher, quoted in Gertz, “Chinese Military Capable of Jamming U.S. Communications System.” The Washington Free Bacon. 2013.

[9] Quoted in Hiding in Plain Sight, The U.S. Navy and Dispersed Operations Under EMCON, 1956–1972. Angevine. 2011.

[10] These diminished C2 capabilities mimic what should be expected during modern command and control warfare.

[11] Angevine, p. 11.

[12] How to Make an Aircraft Carrier Vanish. Associated Press. Norman Black. 1986.

[13] An F/A-18 pilot described the effects as “crushing” during an interview with this author.

[14] “Manage Uncertainty With Commander’s Intent.” Harvard Business Review. Chad Storlie. 2010.

[15] Composite Training Unit Exercise and Joint Task Force Exercise are the final two training events for a strike group.

[16] The United States Air Force is ahead of the Navy in this pursuit. See “Pilot Shuts Off GPS, Other Tools to Train for Future Wars.” Air Force Times. Brian Everstine. 2013.

Preparing Leaders for #TheFutureOfWar

Leveraging Communities of Practice

Recently, we tuned in for New America Foundation’s Future of War conference and watched as the military took some hits for its lack of strategic thinking, inability to work with civilian leadership, and being unable to adapt. None of these charges are new or far off the mark. As former Undersecretary of Defense Michele Flournoy pointed out, we need to reward the behaviors we want. This largely is directed at personnel and how the military develops its leaders.

To prepare for any future war, we need to reassess how we retain, educate, and promote talent. This will help us produce leaders that can think strategically and adapt to ever-changing warfare. Time matters when it comes to preserving and improving our own capabilities and we cannot afford to spend years slowly adapting to an enemy on the battlefield. While major changes to our personnel system may be forthcoming, it will take time to enact them, so we must find other ways to promote, foster, and reward strategic thinking and the peacetime practices that lead to rapid adaptation on the battlefield.

There is a direct correlation between our peacetime education and wartime adaptation. This type of education is not episodic…it is a life-long process.

In Military Adaptation in War with Fear of Change, Williamson Murray argues,

Only the discipline of peacetime intellectual preparation can provide the commanders and those at the sharp end with the means to handle the psychological surprises that war inevitably brings.

There is a direct correlation between our peacetime education and wartime adaptation. This type of education is not episodic, taking place only a few times throughout one’s career; it is a life-long process. Currently, the military is progressing in the institutional and operational domains of leader development — the professional military education and career experiences that make up the triad of individual professional development. And it is coming up short. To fight future wars leaders must be prepared across all three domains. Beyond reading lists, the various military services do very little to assist individuals in their personal study of war and warfare; individuals lack the incentives to deepen their professional knowledge on a continuous and consistent basis. There are no mechanisms like those Flournoy mentioned to reward positive behavior, let alone those that Murray argues are a prerequisite to wartime adaptation.

…the military should foster, support, and reward individual involvement in communities of practice across the profession that support a life-long study of war and warfare.

Instead of trying to develop institutional programs for life-long learning, as some have suggested, the military should foster, support, and reward individual involvement in communities of practice across the profession that support a life-long study of war and warfare. Military leaders should seek out connections with other leaders in their domain or practice to help advance individual development so that they will be prepared to adapt when the time comes.

Groups like the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum and Military Writers Guild are examples of these new professional organizations that offer the promise of strengthening the self-development domain. Although these specific organizations are new to the defense landscape, the ideas behind them are not. Etienne Wegner-Trayner, a leading researcher on communities of practice, defines them as “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis.”[1] It doesn’t matter if interactions take place online or in person — the key is constant interaction driven by a willingness to participate. These types of networks strengthen the self-development domain in multiple ways. They provide extrinsic motivation for self-study, help individuals develop personal learning networks, and the constant interaction helps develop critical thinking skills.

Historical Precedent for Community-Based Learning

One of the first identifiable communities of practice built on the study of war and warfare began in the summer of 1801 when a small group within the Prussian military came together, and as stated by their bylaws, created an institution:

…to instruct its members through the exchange of ideas in all areas of the art of war, in a manner that would encourage them to seek out truth, that would avoid the difficulties of private study with its tendency to one-sidedness, and that would seem best suited to place theory and practice in its proper relationship.[2]

Meeting of the Reorganization Commission in 1807 by Carl Rochling (Wikimedia Commons)

The Militarische Gesellschaft (Military Society) was founded in Berlin by Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst and a few fellow officers to address the issue of a dogmatic adherence to doctrine and lack of professional study among its officer corps.[3] Their members included officers, government officials, and members from the academic community who met over 180 times and ultimately disbanded in 1805 due to mobilization for the Napoleonic Wars. Their weekly meetings consisted of the presentation of professional papers, book reviews, and a discussion of military related topics posed by its members; also, each year they conducted an operational analysis of a past battle.[4] In addition to their weekly discourse, they hosted essay competitions and published a professional journal, Proceedings, for its members.

The society provided a strong intellectual climate that stimulated its members’ thinking and personal development, setting the foundation for great individual and organizational achievement.[5] Its members, who included historic figures such as Carl von Clausewitz, August Neidhart von Gneisenau, and Gerhard Scharnhorst formed the core group of leaders that quickly reformed the Prussian military following its defeat at the hands of Napoleon in 1806.[6] Sixty percent of its 182 members, half of whom joined as junior officers, became generals. Five of the eight Prussian Chiefs of Staff from 1830–1870, as Prussian power grew to dominate Europe, were also members of the Society.[7]

In a similar, if more modern vein, forums like CompanyCommand and PlatoonLeader have provided an online space for company-level leaders in the Army to discuss problems, share tools, and disseminate best practices. They are communities of practice built around small unit leadership. In their book,CompanyCommand: Unleashing the Power of the Army Profession, the founders of the two websites highlight that the online space benefits individual development, “by serving as a switchboard connecting present, future, and past company commanders in ways that improve their professional competence.”[8]

U.S. Marines receive a sand table briefing before a platoon assault exercise on Arta Range, Djibouti, Feb. 10, 2014. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Erik Cardenas)

The forums also host a reading program called the Professional Reading Challenge, which gives company commanders the ability to blend face-to-face interaction with online discourse. Along with promoting reading, the program encourages members to capture their ideas in writing on the message boards. Recently, the forums added an interactive feature they call The Leader Challenge. Using video interviews of officers from deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq, forum members are presented with a real-life vignette and asked to respond with what they would do if they were in the same scenario. After responding, members are able to read others’ responses and listen to what happened in the original scenario.[9] This process allows leaders to continue to learn from a challenging event which may have taken place four or five years ago. The benefits to members are evidenced by the number of forum participants who came out on the recent Army Brigade and Battalion Commander Selection List.

The Militarische Gesellschaft along with Company Command or Platoon Leader Forums are great examples of how communities of practice assist in the development of its members by encouraging reflection, professional reading, writing, and discourse. As individuals become more active within these communities, they own self-development is strengthened.

Leveraging Communities of Practice for the #FutureOfWar

Communities of practice provide the social incentives required to stay committed to life-long learning. A small-scale study published in 2011 posited that two vital components of self-development are intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The researcher found that recognition by mentors and peers both online and/or offline supports these motivations. As members of the profession join various communities, the social interaction provided will help them in their personal intellectual preparation to successfully lead and make decisions during the next conflict.

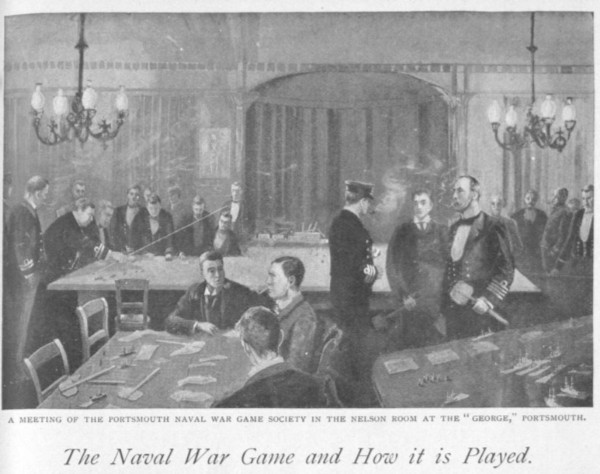

A Meeting of the Portsmouth Naval War Game Society (via Army Group York)

Communities of practice also create opportunities for individuals to develop personal learning networks. The connections made within these groups put individuals into contact with those who they can learn from on a one-on-one basis. Our own experiences validate this argument. For example, while studying at the Naval War College, I relied heavily on a personal learning network built through involvement with the CompanyCommand and Defense Entrepreneurs Forum in developing ideas and for assistance with research and writing.

The constant interaction provided by these communities help individuals develop critical thinking skills. Dr. Antulio J. Echevarria’s essay The Trouble with History, argues that many military professionals focus on the accumulation of knowledge rather than analyzing and evaluating it.[10] Many service members tend to approach reading lists with a check list mentality, instead of using them to rigorously examine concepts and past events. By exploring books and articles and discussing them in a community of practice, individuals are encouraged to move towards a more sophisticated understanding of the material, thus developing the critical thinking skills required of leaders at all levels.

While military professionals used communities of practice for centuries, the career benefits that they provided began disappearing in the Progressive Era. At this time in American history, civil service systems began focusing accession and promotion on Industrial Age mechanisms that were fairer across the personnel pool. This was meant to weed out nepotism and other class- and relationship-based influence.

Military institutions have continued to struggle with how to encourage self-development in leaders, as well as codify this development into a mechanism for career progression.

As the personnel system began to focus more on fairness than effectiveness — thereby diminishing the requirement for leadership to personally develop the leaders that would replace them — the levers used to provide benefit to self-development were removed. Military institutions have continued to struggle with how to encourage self-development in leaders, as well as codify this development into a mechanism for career progression. Our ability to prepare leaders for the development of strategy and to adapt on the battlefield is an outgrowth from these factors.

How do we leverage communities of practice and provide incentives for self-development in today’s military? This is a topic we continue to struggle with — and one we look forward to addressing in this Leadership and the #FutureOfWar series on The Bridge. If you have an idea on what is required in developing leaders for the #FutureOfWar, send us a note or submit your post to our Medium page.

We look forward to the discussion.

Joe Byerly is an armor officer in the U.S. Army . He frequently writes about leadership and leader development on his blog, From the Green Notebook. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Wegner, Etienne, Richard McDermott, and William Snyder. Cultivating Communities of Practice. (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2002), 4.

[2] Charles White, The Enlightened Soldier: Scharnhorst and the Militarische Gesellschaft in Berlin 1801–1805, (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1989), 191.

[3] Ibid., 36.

[4] Ibid., 45.

[5] While correlations between the loss to Napoleon in 1806 and the Militarische Gesellschaft are outside the scope of this article, it is important to address that prior to 1806, the Prussian military culture, organization, strategies, and tactics were all dominated by concepts inherited from Frederick the Great. This rigid adherence to tradition by the majority of the Prussian officer corps negated any of the initial benefits gained by individuals from the military society. It wasn’t until after the Prussian defeat that the society’s members moved into positions of key leadership, thus capitalizing on the relationships and education cultivated and developed prior to the outbreak of war.

[6] Ibid., 207.

[7] Ibid., 49.

[8] Nancy Dixon, Nate Allen, Tony Burgess, Pete Kilner, and Steve Schweitzer,CompanyCommand: Unleashing the Power of the Army Profession, (West Point: Center for the Advancement of Leader Development and Organizational Learning, 2005), 16.

[9] The Company Command website has a thorough explanation of the Leader Challenge at http://companycommand.army.mil/

[10] Echevarria II, Antulio. “The Trouble with History.” Parameters, Summer 1995.http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/articles/05summer/echevarr.pdf (accessed April 11, 2014).