The Chief of Staff of the Army released the results of a study which was designed to determine how the Army can best achieve “success in battle” in the future. I was able to obtain a copy of this report and want to share it here. The Chief convened a group of the best military brains available because he understands that “wars are still fought on little bits of bloody earth, and they are ended when the enemy’s will to resist is broken, and armed men stand victorious on his home soil.”

Preparing for the #FutureOfWar

While it can be said with some confidence that freedom and democracy practiced by an active and educated citizenry provides a solid foundation for the enduring success of any state, America should be wary of using these ideals as measures of an entity’s immediate threat to its security (depending, of course, on the actions of said entity at any given time) or as a mandate for certain types of action against any entity.

Investing in Human Capital for the #FutureOfWar

The Price of Adaptation and Victory

The trajectory of military adaptation and progress frequently diverges along a nonessential, redundant, or contradictory path that impedes the adaptation imperative to achieve a modern, nimble, forward-looking force. Missteps include relying on procurement and acquisition for a technological panacea, entrusting members of the civilian bureaucracy with force structure decisions, succumbing to complacency by believing in the supremacy of American military doctrine and battlefield prowess, or assigning unqualified personnel to influential billets who will are responsible for service-wide decisions based on experiences they do not have. These pitfalls continually threaten to handicap efforts to remain the most advanced force in the world, yet progress and adaptation persist throughout the services, where insightful thinkers seek problems to solve, brainstorm revolutions in military tactics and technology, and quietly carry the banner of Earl “Pete” Ellis, Billy Mitchell, and others into the future of warfare. This movement is powered by human capital, not the adoption of new technology or faddish systems, and demonstrates that the kernel of military adaptability in the 21st century and beyond is people, not hardware or software.

If the capacity to innovate and think beyond the realm of tradition is lost, then we will lose the capacity to adapt and win in the future.

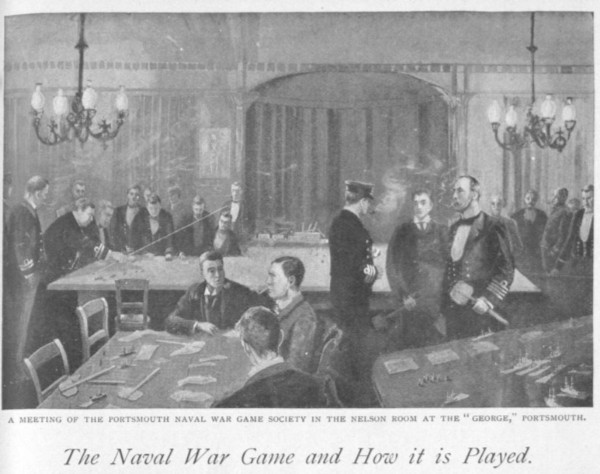

History is replete with examples of technologies that failed to adapt to contemporary challenges of war, or to survive the tactical innovations of adaptive battlefield leaders: the open-order revolution, blitz tactics, the amphibious assault, insurgent tactics, and hybrid warfare each, in a moment, rendered obsolete advanced armaments that were years in development.[1] Moreover, none of successes were anticipated in doctrine or trained in the schoolhouse, but instead were imagined by ambitious, intelligent, creative leaders, who often drew from non-military experience to shape their innovations. It is here, beyond the extent to which the military can develop or buy new technologies, or inculcate its personnel with doctrine, where the American military’s competitive advantage can be found. If the capacity to innovate and think beyond the realm of tradition is lost, then we will lose the capacity to adapt and win in the future. In a lecture last July at Stanford University, visiting fellow James Mattis admonished: “You can overcome wrong technology. Your people have the initiative, they see the problem, no big deal . . . you can’t overcome bad culture. You’ve gotta change whoever is in charge.”[2] The American military, unfortunately, has not embraced this precept, and continues to chase technology so fervently that it has become ingrained in our culture to value it over our human resources. Thus, if we are to secure the human element with which we win wars, we must consider seriously the second of Mattis’ axioms: before we can adapt to the future of war, we must change our culture to value and promote the contributions of the individual.

Inasmuch as our military depends upon innovation and adaptation to succeed, our leadership, military and political, continues to trade salary and benefit cuts, or reductions in force structure, to pay for expensive procurement and acquisition projects. Although the Marine Corps and Army may be able to churn out basic riflemen in a few months, the time required to train skilled pilots, navigators, analysts, and operational planners is measured in years; the time to develop capable organizational managers even longer. These middle- and upper-level managers are essential to the organization, and whereas private enterprise has adapted to reward its leaders appropriately and retain them, there is little accommodation within the military’s personnel management system and compensation scheme to do so. Thus, with hardly a second thought, too many of our best-trained and most-skilled managers leave the military for a second career that is more challenging and rewarding, and as a result the Department of Defense loses its most critical and valuable asset at the moment of its peak potential return on investment. An organization keen to adapt to future warfare more quickly and creatively than its near-peer competitors should be fighting to retain its most experienced, intelligent, and ambitious leaders at the expense of a new armored truck — not the obverse.

To staunch the outflow of talent, the military must pay market-competitive wages to its employees, thereby decreasing the allure of civilian employment and the opportunity cost of continued service in the military. Yet, as Foreign Policy’s Kate Brannan summarized in the January 2015 edition, the trend is in the opposite direction: there has been no significant change to the military’s TRICARE premiums since 1994, the annual cost-of-living adjustments for retirees was cut in 2013, and this year’s budget includes reductions in annual cost-of-living adjustments to base pay.[3] Furthermore, the military egregiously refuses to provide matching contributions to members’ Independent Retirement Accounts through the Thrift Savings Program, only recently considering it as a viable option in future budgets because it offers a cheaper alternative to pensions, rather than offered as part of a competitive pay package to augment pensions.[4] In contrast, private sector leaders have, upon identifying the preeminent role of human capital in competing and succeeding, reinvented employee compensation and benefit packages to pay their employees according to the value they provide to the organization. Firms pay their employees according to novel factors such as specific experience, education, and performance; they provide incentives to continued self-development and additional education; and they share responsibility for future costs by contributing to retirement accounts. As a result, private business continues to regularly attract, reward, and retain the best employees; in contrast, the Department of Defense — which employs more people than Wal-Mart, the nation’s largest private employer — has failed to keep apace, and continues to hemorrhage, rather than retain, talent.[5]

The military’s flat, grade-specific pay structure creates paradoxes on multiple levels, from inequalities between performance and pay to the institutionalization of perverse incentives that reward mediocrity and discourage exceptionalism. An example is easily found at most battalions and squadrons throughout the services: a meritoriously-promoted E-7 preparing to reenlist a third time, with a college degree and a service record filled with commendations, is compensated the same as is an E-6 who has reached sanctuary at 18 years despite being passed over for promotion twice, failing to pursue additional education or development, and earning but a single deployment ribbon. The underpaid E-7 adds value to his unit and the organization daily, and has the necessary qualities to innovate and win on the battlefield; the strap-hanging E-6 is dead-weight, in garrison and overseas. Unfortunately, both are, in terms of the price the military is willing to pay for their efforts, of equivalent value to the organization, a case of economic inefficiency and wage inequality. Furthermore, each is aware of the discrepancy between his productivity and wage (and likely that of the other’s), so the E-6 glibly carries on as he always has, secure in the knowledge he can soon retire with a pension, while the E-7 feels undervalued and begins considering leaving the service for better pay and treatment in the private sector.

…if the American military wants to retain the human capital it needs to innovate and succeed, it must revise the existing personnel management and compensation schema…

Whereas examples of inequality between ability and pay are tangible and quantifiable, the second-order effects of the military’s antiquated compensation regime and its inherent failings are theoretical and less easily measured. The existing paradigm views each service member as interchangeable with his or her peers within grade, with the explicit assumption that no individual possesses distinguishable skills or experience. Time-in-service and time-in-grade pay scales assume that each individual within a peer group has the same marginal productivity, and that an individual only becomes more valuable to the organization once promoted. This pay architecture has institutionalized a structural disincentive to perform at a higher level than the average member of a particular rank and peer-group, which curtails initiative and achievement, and reduces marginal productivity. Simultaneously, this compensation regime encourages others to work less diligently than they may otherwise do, because there is no cost to underperformance. In adapting to future warfare, if the American military wants to retain the human capital it needs to innovate and succeed, it must revise the existing personnel management and compensation schema so that its employees are equitably compensated, and the disincentives within the system are corrected.

While it is absolutely essential to continue investing in research and development, an area in which the American military continues to dominate even its nearest peer-competitors, America will only retain this relative advantage over its adversaries if it is prepared to pay for the best leaders and managers it has trained. To do so, there must be a paradigm shift on two levels: first, that service members are the most valuable and critically important weapon in our nation’s arsenal; second, that it is desirable to compensate members individually. While the military already pays extra for special skills, these bonuses and incentives offered to individuals who are skilled in handling explosives, shooting pistols, flying jets, or speaking a foreign language do not retain organizational managers and leaders, only the trigger-pullers. In contrast, individuals with MBAs, advanced degrees, and civilian job experience relevant to their field or organizational management generally are not rewarded for their unique skills. They, too, deserve a higher paycheck than their peers, but their paychecks remain unchanged because these skills are not considered critical in the current American military culture.

Transitioning from the military’s current archaic compensation regime to a more complex, competitive system does not require innovation, merely the adaptation of systems within existing Department of Defense protocols, such as Foreign Language Proficiency Pay. The next generation of compensation packages would include salary augments for: individuals with corporate management experience, advanced degrees, sustained performance in the top 20% of a peer group, operational deployment experience, and even relevant civilian job experience. In so doing, the military will signal its employees that it values its human resources, recognizes unique skills and contributions to the organization, and is committed to rewarding exceptional performance. These signals will contribute to greater loyalty to the organization, and a clearer sense of equity within the workplace, each of which contributes to improved retention efforts, higher productivity, and thus a greater capacity for innovation and adaptation. Similarly, salary reductions would be taken from marginal performers in other cases, creating tiered disincentives to under-performance. Together, a new compensation-based incentives paradigm will contribute to a change in military culture in which the contribution of the individual is encouraged, the adaptability of the organization strengthened, and overall quality of personnel is sustained, if not improved.

Additionally, correcting the perverse incentives of the existing compensation paradigm to one that encourages adaptation, initiative, and innovation, will create a culture in which the human element is truly recognized as the most lethal and essential weapon in America’s arsenal.

America’s current military leadership should take a cue from private firms that have been listening to former military leaders like James Mattis for years — and finding considerable success as a result. We may reasonably expect that by incorporating the competitive practices employed by private firms for decades, the American military could achieve similar results (or perhaps more exceptional results considering its monopoly on public defense). In so doing, the military will begin to transition toward a more malleable, adaptable, and mobile organization, akin to the giants of private industry like Apple and Microsoft, and away from the plodding, predictable bureaucracy it is. Additionally, correcting the perverse incentives of the existing compensation paradigm to one that encourages adaptation, initiative, and innovation, will create a culture in which the human element is truly recognized as the most lethal and essential weapon in America’s arsenal.

Without this first step towards transition, no degree of adaptation and innovation in training, education, promotion, or force restructuring will succeed, because the benefits of those investments will be lost when the individuals in whom we invest leave. It will further evolve military culture to focus organizational priorities on the value of the individual in the same way that mission command, the doctrinal foundation of our operational flexibility, emphasizes operational flexibility via decentralization.

Ted Ehlert is an armor officer in the U.S. Marine Corps, and is currently learning Japanese at the Defense Language Institute-Monterey as a Foreign Area Officer-in-training. The opinions expressed are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] English, John A. and Gudmundsson, B. I. On Infantry: Revised Edition. Praeger Publishers (Westport, CT: 1994): 1.

[2] “4 Lessons Every Business Leader Can Learn From Legendary Marine General James ‘Mad Dog’ Mattis,” by Paul Szoldra, in Business Insider, 18 July 2014. Accessed 3 March 2015, http://www.businessinsider.com/mattis-leadership-talk-2014-7.

[3] “Report: Panel Recommends Overhauling Military Retirement Benefits,” by Kate Brannan, Foreign Policy, 30 January, 2015. Accessed 3 March 2015,http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/30/panel-recommends-overhauling-military-retirement-benefits/

[4] The Final Report of the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission, 29 January 2015. Accessed 8 March 2015, mldc.whs.mil/public/docs/report/MCRMC-FinalReport-29JAN15-LO.pdf.

[5] “The 10 Largest Employers in America,” by Alexander E. M. Hess, USA Today, 13 August, 2013. Accessed 11 March 2015,http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2013/08/22/ten-largest-employers/2680249/

The Gestalt of Warfare in the Flow of Time

Though it seems war will not change its faces in the coming decades, war has a future, and one of its ends is peace. We have still to see whether the end of war comes about via some technological, humanity-ending armageddon or a technology-mediated, people-centered peace. Yet more data points to consider on the terrain of time.

Embrace the Renaissance for the #FutureOfWar

Developing Diverse Cultural Knowledge

In the Army it is common to hear someone say, “Embrace the suck” to prepare for the rigors of combat. Corollary of our recent wars, however, is that we may need to “Embrace the Renaissance” to prepare for future war. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan showed that we needed renaissance-like traits in our leaders and formations to inculcate the diverse impact of culture. Ample evidence exists that a lack of cultural understanding led to mistakes from the tactical to the strategic level. Similarly, the future security environment will be driven by a broad array of culturally driven actors while our fiscal constraints will increase our dependency on diverse cultures to advance our interests. These realities of future war necessitate enhanced cultural immersion to broaden and encourage renaissance traits within our military formations. Our ability to adapt and think strategically in this future begins with identifying, developing, and rewarding intellectual curiosity in our leaders while nurturing an organizational culture that embraces diverse cultural exposure and development.

The Army’s view of the future is that a complex and dynamic mix of cultures will contribute to the competitive environment that will challenge U.S. interests.[1] A recent human performance paper published by the Army describes the importance of cultural understanding:

“Cultural understanding is instilled through regional alignment, broad cultural appreciation, professional judgment, and language proficiency. The Army of the future must produce leaders, at every level, who think broadly about the nature of the conflict in which they are engaged. They must have a nuanced appreciation of social context, and an ability to develop strategically appropriate, ethical solutions to complex and often-violent human problems. Future leaders must innovate rapidly on the battlefield. They must have a highly refined sense of cultural empathy and a social intuition for their operational environment.”[2]

In Head Strong: How Psychology is Revolutionizing War, Michael Matthews agrees with this assessment and explains the increased importance of respecting cultural needs and employing subtle approaches to win future war. He describes the near decisive impact that cultural mistakes will make given immediate and global dissemination of war images.[3]

Major Larry Workman reflected renaissance-like qualities before deploying his company to Afghanistan. His cultural astuteness contrasted well with the ignorance some showed such as urinating on dead Taliban or burning the Koran. He identified religion, politics, sport and food as four pillars of any culture. He ignored sensitivities about religion and politics and embraced both immediately by noting, “We all come from Abraham” when he first met his Afghan counterparts. He eventually built such a rapport that combined Christian and Muslim services were conducted and attended to by local village leaders. He assigned soldiers to learn Polo prior to deployment to better understand the Afghan sport of buzkashi. He set up a soccer team prior to deployment to ensure his soldiers were comfortable building relations on the field of friendly strife.[4]

Renaissance connotes many traits but potentially none more important than culturally astute.

These acts reflect renaissance-like traits that are needed at every level of command. The term “renaissance man” came out of the Renaissance and described a cultured person who was knowledgeable and educated or proficient in a wide range of fields. The description applied to Renaissance figures that performed brilliantly in many different fields such as Leonardo da Vinci. Some might call them polymathic or worldly individuals who have expertise that spans a significant number of different subject areas and are known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve particular problems. They are curious, traveled, intelligent, knowledgeable, artistic, physical, social and confident. Renaissance connotes many traits but potentially none more important than culturally astute.

Renaissance, polymath, and worldly denote cognitive attributes that overcome biases and heuristics in decision-making while negotiating foreign cultures. Patton said, “I have studied the German all my life. I have read the memoirs of his general officers and political leaders. I have even read his philosophers…I have studied in detail the accounts of every damned one of his battles. I know exactly how he will react under any given set of circumstances…Therefore, when the day comes, I’m going whip the hell out of him!”[5] Patton was a renaissance man who knew his enemy and overcame otherwise crippling decision-making biases and heuristics. His intellectual curiosity, driven by innate attributes, exposure, and desire to win filled a reservoir of instinct making him a genius in war.

Intellectual Curiosity

Rapid adaptation in future war requires intellectually curious leaders now to fill their own instinct reservoir. A comprehensive report on the psychology of curiosity defines curiosity as “a form of cognitive induced deprivation that arises from the perception of a gap in knowledge or understanding.”[6] In other words, one must know and accept they don’t know something and have an intense desire to learn about it. Exposure to different environments and reasoned ideas is the first step to magnifying the light of diversity though many lack these opportunities prior to joining the military. Our geographic isolation and relative supremacy may lead to a false sense of American exceptionalism that impedes intellectual curiosity. Our culture may be one of our primary obstacles to intellectual curiosity, mental agility, and cultural understanding.

While more ambiguous than and indirectly contributing to other attributes such as agility, innovation and results, ‘inquisitiveness’ is also important to achieve the results we desire to not be more directly assessed.

Overcoming this obstacle starts with identifying the right innate attributes required in our leaders. In the Army’s manual on leadership, the term ‘inquisitiveness’ is buried within within the discussion about Army leader intellect. While more ambiguous than and indirectly contributing to other attributes such as agility, innovation and results, ‘inquisitiveness’ is also important to achieve the results we desire to not be more directly assessed. For these reasons, a sub-category called ‘Intellectual Curiosity’ should be added to the attribute category ‘Intellect’ in the Army leader model. ‘Intellectual Curiosity’ is a foundational requirement for mental agility, sound judgment, and innovation. It should replace ‘Interpersonal Tact’ that is largely redundant with aspects of ‘Character’ and ‘Presence.’ Intellectual curiosity should describe the level to which one has a desire to invest effort into learning about the unknown.

Awareness, Understanding, and Expertise

The military must then build off the core individual attribute of curiosity by prescribing more precise organizational training and educational requirements for cultural development. Commanders require organizational decisions about what level of effort is required to prepare cultural leaders to execute Phase Zero (shaping) and Phase Four (stability) operations. Our military’s joint doctrine accounts for the importance of culture in operations with the term well integrated into Joint Publication 3–0 Operations. This document, however, uses the terms expertise, awareness and understanding interchangeable in just one paragraph to indicate the level of skill required.[7]

Definitions of terms shouldn’t paralyze execution, but providing a coherent requirement based on the future environment enables subordinate leaders to prioritize requirements and manage risks in a highly requirement-competitive environment. The Chairman of the Joint Chief’s professional military education (PME) guidance introduces and defines another term, cultural ‘knowledge’, as “understanding the distinctive and deeply rooted beliefs, values, ideology, historic traditions, social forms, and behavioral patterns of a group, organization, or society; understanding key cultural differences and their implications for interacting with people from a culture; and understanding those objective conditions that may, over time, cause a culture to evolve.”[8] By this definition, cultural knowledge is a relatively comprehensive level of cultural skill that imbues leaders with the capacity necessary to succeed in a multi-cultural environment. This definition is a perfect target for educating and training most leaders and organizations.

The August 2014 Army Regulation 350–1 “Army Training and Leader Development” defines cultural awareness, understanding, and expertise as the three required levels of individual cultural capability. First, ‘awareness’ is the lowest level of cultural capability that includes fundamentals, self-awareness, and functional knowledge. Second, ‘cultural understanding’ is similar to the Chief’s definition of ‘cultural knowledge’ and “denotes a firm grasp of cross-cultural competence (3C) and a comprehensive level of regional competence. Generalist soldiers at this level are able to accomplish the mission in a specific geographic area.” It further describes, “Cross-cultural competence (3C) does not focus on a single region. It is a general awareness of the cultural concepts of communication, religion, norms, values, beliefs, behaviors, gestures, attitudes, and so forth. Also, 3C involves self-awareness of one’s own culture and the skills to interact effectively with other cultures.” Cultural understanding is the target objective for generalist leaders in the Army. Third, ‘expertise’ denotes sophisticated cultural competence to include strong language skills.

The Army’s current definitions are adequate if the Chairman’s concept of ‘knowledge’ is well integrated with the Army’s concept of ‘understanding.’

Another comprehensive way to define skill level is through Georgetown University’s National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC). They define cultural awareness as “being cognizant, observant, and conscious of similarities and differences among and between cultural groups.” They call it the “first and foundational element because without it, it is virtually impossible to acquire the attitudes, skills, and knowledge that are essential to cultural competence.”[9] Developed for the domestic health care industry, cultural competence means that organizations and individuals “have the capacity to (1) value diversity, (2) conduct self-assessment, (3) manage the dynamics of difference, (4) acquire and institutionalize cultural knowledge and (5) adapt to diversity and the cultural contexts of the communities they serve.”[10] This definition sets the standard for an organizational culture that embraces culture in every aspect of operations.

The Army’s current definitions are adequate if the Chairman’s concept of ‘knowledge’ is well integrated with the Army’s concept of ‘understanding.’ As defined above, ‘knowledge’ hits the sweet spot of necessary individual skill. The NCCC concept of competence should be incorporated into organizational standards. Current military training and educating goals focus on individual skills and would improve with organizational level objectives. Coming to terms with the definitions sets the bar and starts to provide objective goals of education and training to meet the challenge of future war.

Training and Education

Students taking part in joint professional military education at the Naval War College | https://www.usnwc.edu/Academics/Catalog/RightsideLinks-(1)/2012-2013.aspx

Next, the military must clearly define the requirements and measures necessary to prioritize and assess cultural development. The CJCS’s 2012 Officer Professional Military Education guidance directs that cultural knowledge is only a component of pre-commissioning education and only directs that culture be a factor considered while shaping policies, strategies and campaigns in military education post-commissioning. The Chairman’s six Desired Leader Attributes include leaders with environmental understanding, leaders that anticipate and adapt, leaders that use mission command, leaders who lead transitions, leaders that make ethical decision making, and leaders who use critical thinking.[11] Culture is a contributing factor to each of these attributes though not stated expressly in the guidance. The Chairman’s 30 October 2014 Notice, Joint Training Guidance, does not use the word culture once in the entire document. Of the thirteen high-interest training issues, none of them address culture directly.[12]

The Army only mandates that institutional education programs address cultural awareness training — the foundational element. There are no mandatory steady-state requirements for organizational training of ‘awareness’ or ‘understanding.’ It does not direct ‘awareness’ training within the units nor does the Army mandate that training or education move to the ‘understanding’ level in either operational units or institutions. Any enterprising and audacious commander will exceed this standard but have to do so at the risk of completing other mandatory requirements. Finally, other than language skills, the Army appears to say in AR 350–1 that there is no precise way to measure cultural awareness or understanding. Despite our institution acknowledging the importance of cultural immersion, the message implies that it is a low priority for training and education.

To better clarify and prioritize, cultural awareness must be a pre-commissioning source requirement similar to all other foundational elements of military leadership. Once commissioned, leaders achieve cultural understanding through life-long learning requirements including PME, organization training and operations, and self-development. Officers should reach and validate required levels of defined cultural understanding by the point they depart intermediate level education. Non-commissioned officers should receive awareness training and validation through the rank of E-4 and then achieve validation of understanding prior to promotion to the rank of E-8. Specific regional understanding is the requirement of the aligned or deploying organizations and can be tested locally through individual examination and organizational exercises. Organizational competence requirements integrated into Mission Essential Task List evaluation requirements provides broader unit competence assessments. Specific expertise requirements remain as defined by the Army for advanced skill requirements. Those who achieve skill qualifications might receive an additional skill identifier to provide some minor incentive and acknowledgment.

To achieve these goals, the institution can simply improve on the margins in many areas. Existing PME guidance can be stronger and be better integrated into PME programs. Joint Guidance should require PME to achieve cultural ‘understanding’ or ‘knowledge’ benchmarks. During Joint Military Operations (JMO) and National Security Decision Making (NSDM) trimesters at the Naval War College, culture is not well integrated into the core curriculum. For example, of 24 leaders analyzed in the Leadership sub-course to NSDM, only two were non-western thinking leaders (Indira Gandhi and Deng Xiaoping). In strategy, there are looks at regional economics, sources of conflict, and American interests but no serious look deep into the cultural core of politics, war, religion, family, food or sport. The base material for both JMO and NSDM has extremely few foreign views of operations or strategy. These isolated examples depict broader challenges with determining the total content of professional military education.

The lack of political ideology, philosophical or religious training in most core institutional programs is shocking given the level of influence they bear on foreign and domestic decision-making.

Currently, cultural understanding is too dependent on self-study and should be further emphasized within the PME systems while relegating other, less critical requirements to self-study or operational units. The lack of political ideology, philosophical or religious training in most core institutional programs is shocking given the level of influence they bear on foreign and domestic decision-making. For example, a quick read of Plato’s Republic might enlighten many as to why numerous regimes control the information their people receive. The history of Buddhism, Hinduism, or Confucianism beliefs might reinforce the President’s direction to re-balance to the Pacific. Our PME should be rigorous, enlightening, and less technical. Softer skills should penetrate deeper into beginning institutional education such as experiencing Thucydides, Sun Tzu and Clausewitz before War College where many experience them specifically for the first time.

Foreign Service member exchanges within the schools are very positive, but more can be done to promote deeper cultural integration and understanding in the schools. Despite the presence of a vast array of foreign officers in our PME systems, there is not enough done to create a truly immersed environment. It often appears that they are primarily here to learn from us versus us from them. Mandated fun has always been an effective tool for commanders to build cohesion. There should be more mandated fun in PME to better integrate our foreign resources. Deliberately assigning foreign officer ‘battle buddies’; inviting officers to sponsored cultural events; better integrating foreign officers in seminars; and mandating ‘show and tell’ events by foreign officers improves the effectiveness of an amazing asset already available. Further exposing foreign thought into our relationships and curriculum at every level of the military institution germinates exposure to broader thought.

Operational Immersion

Many operational methods of cultural immersion are in place but marginally executed. Shaping operations, through Theater Security Cooperation Programs, constitute the majority of global military engagement outside of combat zones. Hundreds of combined exercises, subject matter exchanges and missions are conducted annually to increase relations and interoperability. These missions often produce fine training results but often miss opportunities to increase cultural understanding significantly. In one example, an engineer platoon deployed to Northern Thailand to construct a school in partnership with Thai and Singapore military engineers. The platoon lived at the job-site with their military counterparts and within the local village. Over 40 days, a deep level of cultural understanding became a force multiplier. The platoon leadership felt comfortable and deeply integrated with the local community. Two years later, the leadership remains friends through social media with many of those they worked with closely during the project.

A soldier supports members of the Philippine Army as a part of Operation Enduring Freedom-Philippines.

Two months later, this same platoon deployed to the Philippines but lived in a resort isolated from the job site, the community, and their host-nation counterparts. They completed the mission but built no significant relationships. The design of the mission and incorrect criteria led to the loss of opportunity. The project site location created a security challenge and difficulty providing for American level quality of life. This miss-step happened because the wrong objectives were a priority. The priority became building something rather than developing relationships. Had the priority been building relationships, the choice of a different project mitigates the security and comfort issues. Doing this, therefore, enables deeper Filipino cultural understanding in some very young leaders and soldiers.[13] Overly conservative force protection rules often do more harm than good on these missions. Many times, force protection is an excuse to succumb to American comfort desires. If building cultural understanding is an identified priority for these missions, it will change the way they are planned and executed. It will increase the renaissance-like characteristics of those who participate.

While institutional education and unit training operations create domains for cultural immersion, extensive self-study is required to reach the genius expected of our future senior leaders. General Patton likely did a majority of his German studies on his own accord. Similarly, those who aspire to be great in our military will seek out the same individual development. But as the military withdraws back within our borders, the number of foreign assignment opportunities are dwindling and reducing foreign exposure opportunities. The military can, however, inspire an intense quest for knowledge with innovative exposure techniques. One idea to generate enthusiasm is to build from efforts at the military academies and allow our best to travel for an extended period in countries of interest. [14] Not only building renaissance skills, this opportunity rewards their demonstrated intellectual curiosity and sparks intense life-long learning.

The Army’s Military Personal Exchange Program is a long-term personnel exchange between the U.S. and a foreign military and should be expanded to support Security Cooperation and cultural understanding. An Australian engineer officer served in the 65th Engineer Battalion in Hawaii and was instrumental in conveying a different viewpoint. Similarly, a British infantry officer served within the 1st BCT, 10th Mountain in Iraq and provided yet another creative perspective.[15] Due to funding constraints, however, the Australian exchange program ended, and the British exchange was only combat related. These exchanges are expensive due to the duration and overly bureaucratic to execute. Shortening the military exchange to 6 to 12 months as a temporary change of station or extended temporary duty assignment from 12 to 36 as a permanent change of station reduces the costs to the government while still capturing many benefits. Similarly, the general policy of one-for-one should be relaxed to allow for more American officers to work within foreign militaries. Often, the foreign military cannot afford the cost of sending their officers to America.

Executing this program under the umbrella of ‘sister-units’ similar to ‘sister-cities’ by aligning specific American battalions with specific foreign battalions might generate a long-term relationship, momentum, familiarity, and cultural understanding. A fascinating expansion may include a concept similar to exchange programs executed in high school. The exchange of junior officers and noncommissioned officers who have the opportunity to live in the house of a foreign sponsor for three to six months would dramatically enhance cultural immersion and understanding. If all done through the concept of sister units, these programs would gain unit emphasis, momentum, accountability, and spirit. Initiating these programs through our tried and true allies such as the Canadians, Australians and British simplify the obvious concerns of language and force protection until these aspects can be more precisely developed and managed for countries further on fringe of our cultural understanding.

The intent is to spark an interest in junior leaders that will mature as their career progresses.

In the same vein, Foreign Area Officers are inculcated to a region partially through a year-long series of personal travel. That same methodology employed by regionally aligned units can broaden cultural understanding. For example, a junior officer or noncommissioned officer on a three-year assignment to the Pacific might be offered 30 days of permissive temporary duty to travel countries of interest in the Pacific. The intent is to spark an interest in junior leaders that will mature as their career progresses. Many simply do not have the opportunity or means prior to joining the military to become physically exposed beyond our borders. There are few strings attached to this sabbatical other than general guidelines such as 30 days permissive temporary duty, checking-in with the embassy, no uniform or grooming requirements, maintaining accountability with unit, providing summary reports describing culture lessons, and preparing unit cultural training support packages. Not to be confused with Japanese spies in South Asia prior to WWII, these soldiers are on sabbatical experiencing new worlds.

Potentially, two, one-month sabbaticals are authorized in the first ten years of a soldier’s career. In most regions, one might envision that the traveling soldier can experience three or four countries of interest. In the Pacific, for example, a soldier may visit China for a couple weeks followed by days spent in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. This abstract concept is likely more easily implemented than in reality, but the concept enables our success in future war and is exciting for our junior leaders who have expressly made known their intense desire for more extensive cultural exchange.[16] Not only do these enlightened concepts enhance our cultural understanding and thereby our decision-making but they also appeal to the self-interest of those we want in an adaptive military. This idea should resonate with senior leaders who had the opportunity to travel Europe with impunity or those who had the opportunity and means to travel on their own.

Conclusion

Doctrine is understandably vague in the particular desired cultural end-state, but more can be done to precisely define terminology and education / training requirements. Solid guidance eliminates ambiguity and encourages the joint community to integrate culture effectively in professional education and training. In an environment with too many directed requirements, focus on culture understanding will not be a priority for non-deploying commanders without top-level focus and accepting risk in areas less essential in future war.

The value or priority we place on these efforts will be a direct reflection of the value we place on shaping and stability operations or winning without fighting. If, as we might expect, we evolve back to a force driven by the two weeks or more of intense combat at a training center, we will be hard pressed to replicate the slowly emerging impact that cultural understanding has on protracted operations. By nature, we will be drawn to the kinetic or dominating fight and forego the humanities that underpin all conflict. Our home-station training and training center operations will never properly replicate the cultural dynamics painfully learned from over a decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Renaissance-like characteristics spring from intellectual curiosity that must be a recruiting, developing, and assessing focus. Opening the door for foreign exposure and immersion opportunities is essential to overcoming American biases and motivating curiosity. As defined by the Army, gaining cultural expertise is a long process best focused on those such as foreign area officers who operate in the culture daily. But, getting to cultural understanding as defined by the Army or cultural knowledge as in joint doctrine requires opportunity and inspiration. Our military and nation will be far better off if we do more to arouse that renaissance-like intellectual curiosity now. If so, our leaders will have the strategic perspective, mental agility and access to diverse communities of practice to win the future war.

Aaron Reisinger is an officer in the U.S. Army currently attending the Naval War College. The opinions expressed he opinions expressed are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, Operational Environments to 2028: The Strategic Environment for Unified Land Operations, (Fort Eustis VA: TRADOC G2, August 2012).

[2] U.S. Army, The Human Dimension White Paper A Framework for Optimizing Human Performance, (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combined Arms Centers, October 2014).

[3] Michael D. Matthews, Head Strong — How Psychology is Revolutionizing War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[4] Larry Workman, MAJ, United States Army, phone conversation on 13 February 2015.

[5] Roger H. Nye, The Patton Mind (West Point Military History, Avery Publishers, 1994)

[6] George Loewenstein, “The Psychology of Curiosity: A Review and Reinterpretation,” Psychological Bulletin 116, no. 1, American Psychological Association, Inc., (1994): 75–78.

[7] Chairman, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Operations, Joint Publication (JP) 3.0 (Washington, DC: CJCS, 11 August 2011), III-19.

[8] Chairman, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Instruction 1800.01D: Officer Professional Military Education Policy (Washington, DC: CJCS, 5 September 2012).

[9] National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University,http://www.nccccurricula.info/awareness /

[10] National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University,http://nccc.georgetown.edu/foundations/frameworks.html.

[11] Chairman, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Instruction for Joint Training Policy for the Armed Forces of the United States (Washington, DC: 25 April 2014).

[12] Chairman, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Instruction: 2015–2018 Chairman’s Joint Training Guidance (Washington, DC: 30 October 2014).

[13] Examples cited were from the deployment of 2nd platoon, 643rd vertical engineer company, 84th engineer battalion in 2013 to Thailand for Cobra Gold 13 and the Philippines for Balikitan 13.

[14] The academies have numerous requirements for language training and provide many opportunities for spending a semester abroad living with a family and studying in a host country. In my opinion, language training is only marginally useful unless combined with at least 6 months of immersion in a nation speaking that language.

[15] Both are personal experiences of mine while serving at the Operations Officer for the 65th Engineer Battalion and a Transition Team Chief with 1st BCT, 10th Mountain deployed to Kirkuk, Iraq.

[16] In a review of the Army Operating Concept at Fort Leavenworth from Feb 24–26 2015, nearly 100 Army captains participated in The Captain Solarium and recommended in the out-brief to Army Chief of Staff General Odierno that the Army expand cross-cultural understanding.http://www.army.mil/article/143655/Expand_cross_cultural_understanding__captains_tell_the_CSA/

The #FutureOfWar and the Fight for the Strategic Narrative

Stories or narratives are an important construct that unite and sustain human communities. These narratives are a fire around which individuals, nations, and peoples gather. Based on them we celebrate a common history, language, or culture and they have the power to inspire a sense of meaning for life — they provide hope for the future.

Stories provide ideas which Kennedy referred to as “endurance without death.” For as long as narratives form the fabric of human existence, and for as long as war remains a human endeavor, the fight for the strategic narrative during times of conflict becomes imperative. Consequently, any discussion of the future of war must include consideration of how the battleground for ideas can be won through a persuasive story that can inspire action in people and government and thus the military.

‘A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on. Ideas have endurance without death’.

John F. Kennedy

Strategic narratives also help develop the rationale for war efforts. Without them nothing rallies or binds people to a common cause. More importantly, without a strategic narrative, there is no story that provides an alternative voice to those whom we fight. This is evident in the fight against extremist organisations such as ISIL, who has developed a glossy and sensational communications product that creates emotional connections with people and has proven to be a highly effective recruitment tool.

The Importance of the Narrative to Human Existence

When I think of the word “narrative,” I immediately think of those various human civilizations that have passed on their language and culture through storytelling. Australian Aborigines make reference to “The Dreaming” or “Dreamtime,” which has various meanings within different Aboriginal groups. However, it can be summarized as “a complex network of knowledge, faith and practices that derive from stories of creation, and it dominates all spiritual and physical aspects of Aboriginal life.”[1] This network of knowledge has been passed on over thousands of years through generations sharing stories. Or simply through oral histories.

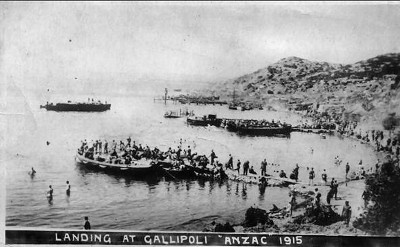

According to one Marine Corps officer, LtCol John M. Sullivan, in an article called ‘Why Gallipoli Matters: Interpreting Different Lessons from History’, “[t]he very word ‘Gallipoli’ conjures up visions of amphibious assault and failure of what might have been.” Gallipoli was indeed a military failure, but that aspect of its narrative has become subsumed by a stronger story about the birth of the Australian nation, an idea that was borne out of the work of Australia’s official war correspondent, C.E.W Bean. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings and hence the spiritual birth of Australia, and the dominant narrative will take on an irresistible force with celebrations across the country, which will be spread over the next four years [2]. The facts of the military campaign occupy only a marginal part of the celebrations, reserved only for the military historians or those with a passing curiosity. The details surrounding the events of the 25th April 1915 have been overborne by a greater need for a nation to express its sense of national identity. This highlights that the dry facts are sometimes not as important as the story and the emotions that the narrative conjures in those who engage with it [3].

I wanted to share these examples to highlight the primal nature of stories and their link to human emotion rather than rational human cognition. According to Cody C. Deistraty in ‘The Psychological Comforts of Storytelling’:

‘[s]tories can be a way for humans to feel that we have control over the world. They allow people to see patterns where there is chaos, meaning where there is randomness. Humans are inclined to see narratives where there are none because it can afford meaning to our lives a form existential problem solving.’

Stories also enable an understanding of others and drawing connections with seemingly distant issues.

The Importance of the Strategic Narrative to the Future of War

The importance of narrative, how it powers human emotion, and its relationship to war becomes evident when considered through the frame of Clausewitz’ theory about human emotion within the construct of the ‘paradoxical trinity.’ He said:

“War is more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case. As a total phenomenon its dominant tendencies always make war a paradoxical trinity — composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which is to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and of its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to reason alone.

The first of these three aspects mainly concerns the people; the second the commander and his army; the third the government. The passions that are to be kindled in war must already be inherent in the people; the scope which the play of courage and talent will enjoy in the realm of probability and chance depends on the particular character of the commander and the army; but the political aims are the business of government alone.

These three tendencies are like three different codes of law, deep-rooted in their subject and yet variable in their relationship to one another. A theory that ignores any one of them or seeks to fix an arbitrary relationship between them would conflict with reality to such an extent that for this reason alone it would be totally useless” (emphasis added) [4].

In his book, The Direction of War, Sir Hew Strachan considers that strategy formation in the 21st century neglects the people, which is a significant oversight because “[t]he people are the audience for war” and they must be factored into strategy formulation and operational planning. Strategic narrative is vital in engaging the people — in persuading the adversary’s potential recruits/supporters to either stay out of the fight or to support our efforts; as well as convincing our own populations to support our military endeavors in pursuit of key national interests [5]. For this reason, a strategic narrative is a means to ensuring that the people, military and government “become three in one in reality as well as in Clausewitzian theory” [6].

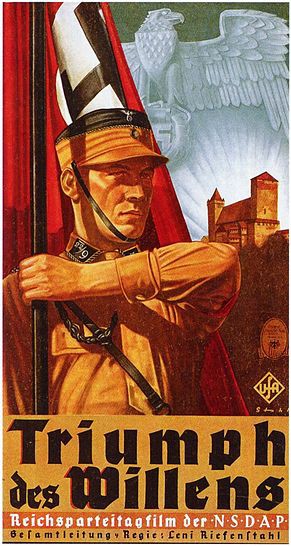

The battle between competing narratives is not new. A battle for ideologies underscored the Second World War. Hitler’s anti-Semitic rhetoric and territorial ambitions were delivered with the pomp and ceremony of rallies and associated symbology. Nazi propaganda films, such asTriumph of Will were aimed at stirring emotion and hitting the German population in the collective ‘feels.’

…they used emotion to convey a message and obtain understanding, rather than dry statistical and bureaucratic language to convince the respective populations of the need to go to war.

On the Allied side of the fight was the seven-part film Why We Fight, which was aimed at emphasising to US servicemen the reasons for US involvement in the war against Germany and Japan, and to unite the nation behind a common cause [7]. These films were effective in that they used emotion to convey a message and obtain understanding, rather than dry statistical and bureaucratic language to convince the respective populations of the need to go to war.

Arguably, it is easier to have a strategic narrative in a total war where there is a clear existential threat to a nation. Limited wars conducted on distant shores are a relatively more difficult to “sell.” For this reason, a strategic narrative is vital in a limited war because there is an ongoing need to keep the people appraised of how the war is unfolding and to maintain their support for the often protracted conflicts that we have so far experienced in the first decade of the 21st century.

A strategic narrative also plays a vital role in providing a protective function (or ‘counter-narrative’) against the story conveyed by the adversary. The large numbers of citizens from many nations, including Australia and the US, going to Syria and Iraq to fight alongside ISIS provides an ongoing reminder of the need to have a ‘counter-narrative’. The difficulties in countering ISIS in this regard is covered off by Simon Cottee’s article in The Atlantic posted here.

A few considerations for how to build an effective strategic narrative, particularly in a counter-insurgency setting, have been discussed by Col. Stephen Liszewski USMC here. Jason Logue, in a previous post on The Bridgealso provided a detailed discussion on how to constructively engage in the fight for the dominant and more persuasive story through the use of appropriate language and having a nested approach to strategic communications.

Preparing Future Leaders

The preparation of future leaders for future warfare that will inevitably involve the fight for the dominant narrative is difficult and will require breaking existing cultural norms. This can be achieved through including the strategic narrative in professional military education; and reacquainting ourselves with strategy formulation.

Professional military education and strategic narratives. When someone mentions the strategic environment, the instant reaction is to start thinking about things like regional military spending, socio-economic and environmental pressures that can widen fissures in the security setting, and pre-existing tensions between countries based on history, etc. However, there is little discussion about the “information environment,” as a subset of the “strategic environment,” wherein competing narratives reside.

This is particularly important when it comes to ‘whole of government’ efforts that direct many elements of national power to a common cause. The fight against ISIL is an example where various elements of national power are engaged, and where a unifying strategic narrative that offers an alternative is imperative. Preparing future leaders to engage in this fight for the dominant narrative is challenging as it requires a change in culture and a broadening of the collective perspective. Perhaps a relatively useful starting point is in professional military education — through war colleges and staff colleges as part of studying strategy; and using a historical study of strategic narratives in past conflicts using Sir Michael Howard’s approach of studying depth, breadth and context.

Reacquainting Ourselves with Strategy

Before an effective and unified strategic narrative can be constructed and deployed as a credible and viable alternative to that offered by the adversary, there is a need to have a strategy that forms the foundation of the narrative. In the fight against ISIL, this seems to be missing. Much of the political oratory regarding actions to be taken against ISIL revolves around mission verbs: “degrade” and “deny” [8]. Arguably, this is not a strategy as it fails to link how military force is to be used to achieve political objectives and is merely declaratory of actions that should be expected in war (i.e., to degrade or deny the enemy). Sir Hew Strachan, in The Direction of War, examined a number of recent conflicts and strongly criticizes national leaders in the United States and Britain for entering into conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan without a clear strategy.

…it is clear that strategic acquaintance must begin with senior military leadership, who are expected to provide advice on the use of military force to civilian leaders…

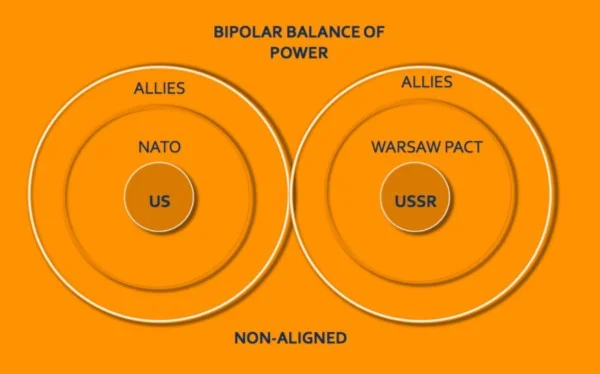

Sir Hew discusses the impact of the Cold War in diminishing the capacity for strategic thought and strategic formulation caused by the conflation of strategy with policy due to the specific existential threat that nuclear war posed [9]. Ensuring that future leaders reacquaint themselves with strategy and its formulation is a significant challenge due largely to the need for a cultural shift. It is not for me to detail how this is to be done, but it is clear that strategic acquaintance must begin with senior military leadership, who are expected to provide advice on the use of military force to civilian leaders in nations where civil control of the military is a fundamental tenet of liberal democracy. It will require a serious, objective consideration of recent conflicts and an examination of where we were found wanting in terms of strategy. This may require the help of experts in strategy (such as Sir Hew) to guide military leaders on this path to strategic re-acquaintance.

The current fight for the strategic narrative is not in our favour; as shown by the multitude of willing volunteers answering ISIL’s call. While a topic such as the future of war evokes mental images of technologically advanced platforms, cyber capabilities, and omniscient battlespace awareness, we cannot forget about the enduring human aspect of war. While war remains a human endeavor, and stories/narratives are a way for humans to use emotion to understand complex phenomenon, the battle for the strategic narrative remains vital. If we fail to engage in this fight, the future of war will look very much like the recent past where we win the tactical engagements but lose the war.

Jo Brick is an Australian military officer who has served in Iraq and Afghanistan, an Associate Member of the Military Writers Guild, and is currently writing a thesis on Australian civil-military relations. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the Australian Defence Force.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] See Australian Museum: http://australianmuseum.net.au/indigenous-australia-spirituality

[2] For a sense of the scale of ‘Gallipoli: 100 Years On’ celebrations, seehttp://www.anzaccentenary.gov.au/

[3] See Dr Peter Stanley, ‘Why does Gallipoli mean so much?’ ABC News Online, 25 Apr 08: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-04-25/why-does-gallipoli-mean-so-much/2416166 (accessed 03 March 2015).

[4] Carl von Clausewitz, On War. Translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, (Princeton: Princeton University Press) 1984, 89.

[5] Hew Strachan, The Direction of War (New York: Cambridge University Press) 2013, 278–281.

[6] Strachan, 281.

[7] Charles Silver, ‘Why We Fight: Frank Capra’s WWII Propaganda Films, MOMA http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2011/06/07/why-we-fight-frank-capras-wwii-propaganda-films/ (accessed 03 March 2015).

[8] See Obama speech:http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/09/10/president-obama-we-will-degrade-and-ultimately-destroy-isil (accesed 04 March 2015).

[9] Strachan, 16.

Cognitive Training to Achieve Overmatch in the #FutureOfWar

The future of war is hard to predict and we have rarely foreseen the next conflict before it has found us. As we transition out of large-scale counterinsurgency and security force assistance operations towards decisive action operations in our training focus, we must pay special attention to what and how we train in this environment. Some might wishfully think that the Army can return to a Cold War-like era where we have a laser focus on the fundamentals of shoot, move, and communicate within the construct of combined arms maneuver. However, the Army’s experiences over the last ten years, and current projections about the future implore us to seek other models to guide our preparation. The Army’s Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) recently published TRADOC Pam 525–3–1, The U.S. Army Operating Concept: Win in a Complex World to help define the future operating environment and challenges.

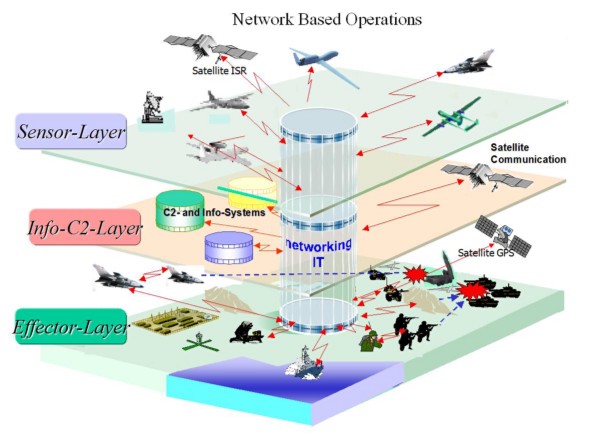

The Army Operating Concept lays out five characteristics and twenty warfighting challenges that can help guide the Army in its preparations for the future of war.[1] The five characteristics are the increased velocity and momentum of human interactions and events; potential for overmatch; proliferation of weapons of mass destruction; spread of advanced cyberspace and counter-space capabilities; and demographics and operations among populations, in cities, and in complex terrain. A common trend across these characteristics is the complex, massive volume of stimuli soldiers will face, and the decentralized decision making required to gain and maintain the initiative in the future.

In the future, the fog of war will be as much about too much information as it has been defined by the absence of information in the past.

Consider the following: urban terrain presents a plethora of stimuli and distractions to the future warfighter. Information collection assets and digital systems present the decision maker with an abundance of data that needs to be analyzed and synthesized into a shared understanding and future operations. All the while, a thinking and decentralized enemy will demand that the Army presents them with multiple dilemmas using innovative ideas, or else we risk ceding the initiative to our adversaries. An interesting aspect of the scenario above is that there is no mention of the basics as we traditionally view them, “shoot, move, and communicate.” Building adaptive and innovative leaders is the best way to win the next war and this can be accomplished by training the cognitive abilities of our soldiers and leaders.

What are the Critical Cognitive Abilities?

The Army Operating Concept mentions the requirement for advanced cognitive abilities within the context of the Human Domain and decision making, but it does not provide any specifics on what or how the Army should pursue these. Army doctrine does not currently address these issues either, so we should look to the fields of cognitive science and systems theory for specifics. The combined theories of these two fields provide us with a decision making model to help identify advanced cognitive abilities. Cognition begins with gathering information and proceeds to processing information, analyzing and synthesizing a conclusion and/or course of action, and finally executing the selected course of action. This model will form the basis for re-examining the scenarios presented previously.

The plethora of stimuli in urban terrain, and the abundance of data that can be gathered from modern information collection assets, challenge soldiers on the battlefield — all of whom must make life and death decisions. In fact, scientific studies support the fact that information overload often results in a decreased quality of decisions.[2] To help overcome this challenge, we must seek to increase our soldiers’ ability to gather information through the filter of trained perceptiveness. Soldiers who are trained in perceptiveness can use these skills to sift through excessive stimulation and recognize significant cues. This advanced situational awareness can help us identify anomalies and indicators to find the proverbial needle in the haystack.

Perceptiveness will provide us with a heuristic technique to assist us in our decision making.[3]

Once soldiers have collected the relevant information, they must then process and synthesize the information into concepts that can be executed as a course of action. Speed of mental processing and the ability to synthesize data into relevant concepts are desirable skills for anyone, but for a soldier this might mean the difference between life and death. So we must ensure our soldiers have these abilities. These skills are particularly advantageous in an age where the global media scrutinizes the decisions of leaders at every level.[iv] Speed of mental processing and synthesis are abilities traditionally associated with staff officers and NCOs, but all soldiers must seek to increase these abilities to gain and maintain the initiative in the future.

Finally, the future will inevitably present soldiers with an adaptive enemy, unique situations, and complex operating environments. These characteristics will require soldiers to apply trained tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) in foreseen circumstances, while having the ability to modify or invent new TTPs in real time for unforeseen situations. The key to adapting and overcoming these challenges in the future will be to foster a spirit of innovation in our soldiers.

How are we training these Cognitive Abilities Now?

Currently, the Army does not deliberately focus on advanced cognitive abilities in its leader development or collective training efforts, but in the future it must do so to achieve overmatch against our adversaries.

The discussion above highlighted four critical cognitive abilities that the Army must focus on: perceptiveness, speed of mental processing, synthesis, and innovativeness.

The Army has a handful of programs that seek to improve perceptiveness and adaptability, but they are not well known and it is challenging for commanders to get their soldiers into these programs. The biggest challenge the Army will face in seeking to develop these attributes will be to design and integrate training and educational efforts to scale across the entire force.

In the near term, the Army has a few niche programs that commanders can pursue to train and educate our soldiers on these advanced cognitive abilities. A non-exhaustive list of existing programs include Advanced Situational Awareness Training, the Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program, Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness or resiliency training, the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS) or “Red Team” training, and Leader Reaction Courses. Each of these programs directly or indirectly addresses at least one of the four critical cognitive abilities.

Photo Credit: Aniesa Holmes. A role player dressed as an Afghan border security officer helps a student enrolled in the Advanced Situational Awareness Training program observe a village from a distance, Oct. 4, 2013, on Lee Field at Fort Benning, Ga.

The Army’s Advanced Situational Awareness Training program of instruction seeks to increase our soldiers’ ability to identify patterns and therefore anomalies in our environment. This advanced awareness will help soldiers identify pre-event indicators that are significant to mission accomplishment.[v] Contractors originally designed Advanced Situational Awareness Training, but the Army has since incorporated it into various professional military education courses, including the Armor and Infantry Basic Officer Leader Courses.[vi] Many aspects of Advanced Situational Awareness Training continue to focus on overcoming the threat of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), but its program of instruction should be able to be expanded to train perceptiveness more broadly.

The Asymmetric Warfare Group’s Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program course promotes critical, creative problem solving to reach innovative solutions to ambiguous situations.[7] This course is an evolution of the Outcomes-Based Training and Education methods that the Army Reconnaissance Course adopted in the mid- to late-2000s. The Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program is focused on promoting adaptive leaders and decision making under the principles of mission command. This course guides students through a series of principles and exercises that educate and train soldiers on perceptiveness, synthesis, and innovativeness.

The Army’s Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program, known primarily for its resiliency training, is designed to help improve human performance across the Army. The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program originated out of a desire to promote resiliency and mitigate against potential risks in our soldiers and military families, but the Army has expanded its goals to include all aspects of human performance. The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program has established a unique and valuable relationship between soldiers and psychologists. The Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness’ cadre of psychologists have a unique insight into cognitive abilities and the broader science that can be harnessed to promote mental processing and other cognitive functions in our formations.

The University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS), better known throughout the Army as the “Red Team,” is another resource that promotes cognitive abilities. Leaders frequently think Red Team training is primarily for educating and training military intelligence leaders to think like the enemy — an almost natural assumption based on their common name — but the UFMCS offers much more. Anyone who has attended UFMCS training, or a discussion facilitated through their instructional methods, can attest to the power of the tools they use to train divergent and convergent thinking. These thinking tools and instructional methods include mind-mapping, storytelling, asking whys, dot voting, meta-questioning, and circles of voices. These discussion and cognitive tools are valuable for analyzing and synthesizing information to reach conclusions or courses of actions.

Photo Credit: LTC Sonise Lumbaca. Soldiers from the 197th Infantry Brigade participate in an adaptability practical exercise using an obstacle course during the Asymmetric Warfare Group’s Asymmetric Warfare Adaptive Leader Program hosted at Fort Benning, Ga. November 2012.

Finally, many Army installations have Leader Reaction Courses that challenge groups of Soldiers to collectively solve unique problems. These courses are frequently used during initial entry training and are thought of as team building exercises, but they should not be limited to these instances. A Leader Reaction Course trains problem solving techniques by encouraging creative and innovative thinking. Each obstacle forces participants to think out of the box and generate unique solutions. Encouraging our soldiers to think like this will help develop innovative minds for the battlefield.

How can we Train Cognitive Abilities in the Future?

The Army must develop a holistic and integrated approach to developing advanced cognitive abilities within our soldiers, leaders, and units. Currently, the Army has a number of niche programs and courses that provide near term cognitive development as described in the previous section. However, to adequately prepare for the future of war, the Army must develop a more holistic short and long term plan to address these abilities. The Army must develop a system to assess and provide continuous training and educational opportunities throughout a soldier’s career.

To assist commanders in monitoring and tailoring their cognitive training efforts, the Army must develop a method of assessing cognitive abilities in all soldiers and leaders. Cognitive abilities can be assessed and recorded similar to how the Army currently tests enlisted soldiers to determine their General Technical (GT) score.[8] The Army must tailor these assessments to measure the aforementioned critical cognitive abilities. The Army’s Centers of Excellence could further shape these assessments to measure any additional cognitive abilities deemed relevant for soldiers in their respective Branch/MOSs. In addition to a mandatory assessment during a soldier’s accession into the Army, these assessments must recur throughout a soldiers career. This will enable individual soldiers to seek feedback and improve their cognitive abilities, while allowing commanders to assess their unit’s capabilities. The feedback provided by these assessments will help commanders develop comprehensive cognitive training plans that are nested with and enhance their leader development plans.

To improve cognitive abilities throughout the Army, the Army must expand current efforts into comprehensive short and long term training strategies. Two viable short term courses of action are to expand the current training capacity of these programs and/or rapidly spread these initiatives at the unit level through a train-the-trainer methodology. In addition to the initial benefits to the soldier, the train-the-trainer methodology is advantageous because it will provide a subject matter expert within each unit, similar to a master gunner or master fitness trainer. The master cognitive trainer can provide advice to the commander to incorporate cognitive training into existing training exercises and/or design stand-alone educational or training events as desired. These short term courses of action will generate additional resources for cognitive development until long range plans can be developed and employed.

In the long term, cognitive training and education should be developed based on the results of the aforementioned assessment tools and integrated into programs such as Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness. Integration with the Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness Program will enable harnessing the unique capabilities of psychologists and advanced cognitive sciences. Additionally, optional courses should be offered at installation education centers and on-line to allow soldiers to develop cognitive skills as another aspect of self-development. The integration of assessment tools, expanded classroom and on-line educational opportunities, inclusion of cognitive development within Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness, and cognitive training incorporated into unit training and leader development programs have tremendous potential towards achieving overmatch against future adversaries.

Conclusions

The Future of War is hard to predict. However, it is increasingly obvious that the basics of shoot, move, and communicate must be expanded to include cognitive abilities. Perception, speed of mental processing, synthesis, and innovation are the four most critical cognitive abilities. We must develop a system to assess, train, and educate soldiers in these abilities to develop our collective capabilities. As mentioned in the Army Operating Concept, the Army must address advanced cognitive abilities and the Human Dimension to provide overmatch against our potential adversaries. Advanced cognitive abilities must be developed to gain and maintain the initiative in future conflicts.

The author would like to thank Mr. Keith Beurskens and the eleven captains in his small group at Solarium 2015. The thoughts above are reflective of this group’s efforts during a week-long discussion and research endeavor where they studied the Army Operating Concept at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Gary M. Klein is a U.S. Army Officer and member of the Military Writer’s Guild. The views and opinions expressed here are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Department of the Army, TRADOC Pam 535–3–1, The U.S. Army Operating Concept: Win in a Complex World, (Fort Eustis, VA: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 2014), p.11–12 and Appendix B. Pages 11–12 address the likely characteristics of future operating environments while Appendix B lays out the twenty warfighting challenges (aka questions) that will drive development of the future force.

[2] Crystall C. Hall, Lynn Ariss, and Alexander Todorov. “The illusion of knowledge: When more information reduces accuracy and increases confidence,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 103 (2007): 277–290.