Azzam’s legacy is a complicated one. It is difficult to pin down the exact extent of his influence and where others have distorted his ideas. Moreover, even though Azzam was critical of the previous era of transnational hijacking and terrorism, he ultimately became the inspiration for a subsequent, more violent movement, one that resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Muslims, most of them at the hands of other Muslims. But as complex as Azzam’s legacy in the evolution of global jihad has been, Thomas Hegghammer’s masterful book will certainly contribute to our growing, collective understanding of his important role.

The Logistics of Terror: The Islamic State’s Immigration & Logistics Committee

Seemingly, the group was defeated after the Anbar Awakening and second Gulf War, but the organization waited patiently in the shadows for the right opportunity to strike back and regain relevance. During the interlude following the second Gulf War and the establishment of the caliphate, the group did what it has always done well—survive.

Changing Calculus and Learning from our Enemies

Suicide Bombing has been the subject of scholarly works and studies in multiple campaigns. For the U.S. military, suicide tactics have been an integral part of the threat environment for well over a decade. Familiarity with the concept generates a bit of complacency, but this is a false familiarity obscuring the reality that suicide bombing has changed in the last decade.

Reflections on Airpower: Offensive Strike

As the Islamic State advance was brought to a stop, coalition aircraft were free to attack the enemy from their front line positions to deep behind into the territory they held. The uncontested hold of the air provides us the ability to target and destroy the support network that keeps the self-declared caliphate fully functioning. From Mosul to Raqqa, the destruction of logistic depots, training camps, communication facilities and financial complexes, in addition to the destruction of their fighting units in direct contact with friendly forces, applies pressure on every aspect of the organization.

Why ISIS Remains a Threat

To be successful in the long term against the threat of the Islamic State, the United States should focus its power on undermining the organization’s core appeal. The United States must recognize the sectarian nature of the Syrian conflict, which enhances the attraction to the Islamic State as the best Sunni Army in Syria. All U.S. policy decisions must be informed by the need to guarantee the rights and future of Syrian Sunnis, while anticipating increased threats from the growth of jihadi organizations within Syria.

Islamic State 2016 and America’s Underperformance on the Twitter Battlefield

The United States has spent far more time agonizing over counter-messaging strategy than engaging meaningfully to exploit the Islamic State’s weaknesses on social media. Whether counter-messaging is capable of delivering results or not, the analysis reveals the United States missed opportunities to exploit Islamic State losses.

The Roles Women Play

It has been some time now since the husband and wife team of Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik committed their act of terrorism in San Bernardino, California–a story that has popped back up in the news because of the FBI court case requiring Apple to unlock the couple’s iPhone. In the aftermath, as a way to determine a motive, investigators initially focused on a garbled message on Facebook left by Malik. The message purported to claim an allegiance to Islamic State (IS) leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. This led many in the media–and armchair analysts online–to confirm that the attack was at least inspired by IS. But digging deeper into the lives of Farook and Malik revealed a more al Qaeda-style ideology. The fact that Malik was involved in the shootings suggests more al Qaeda than Islamic State. Why? Because of the roles women play in each organization.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement at 100

The violence occurring in the Middle East is the result of a revisionist movement, namely the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which seeks to conquer the greater region and expand its caliphate. A group that knows no geographical boundaries, its rapid rise is a symptom of what is widely regarded as the post-Westphalian trend the world has taken. Further, the volatility accompanying years of sectarian division has only been exacerbated by western involvement in the region, a century-old pattern of attempts to dictate the direction of governance dating back to World War I.

Why Saudi Arabia May Be the Next Syria

The Islamic State group (ISIS) is running up against a wall. As national coalitions take a larger role in the fight against ISIS, the group will become increasingly unable to operate on as large a scale as it has in years past, and it will be pushed out of its previously held territories – its decline may take years or even decades, but it will ultimately decline. But although ISIS may deplete its resources and feel increasing pressure from the international community, its members will not simply disappear as the group loses momentum.

Friction and ISIS

Daesh is now meeting what Clausewitz refers to as friction in war, i.e., those factors that sap the war machine of its vitality. In its drive to establish an Islamic Caliphate, Daesh reached out far and wide to project its influence, overextending its capabilities in the process. The developing stalemate across its fronts could indicate an operational pause to consolidate, or it could simply mean that it is reaching the “diminishing point of the attack.” For an organization that sells itself as a dynamic, maneuver-oriented offensive force, Daesh cannot afford to get locked into a defensive war of attrition.

When Fear Drives Policy

In the second installment of the original Star Wars trilogy, the main character Luke Skywalker is prompted to enter a cave on the planet Dagobah by his teacher, the venerate warrior Yoda, as part of his training. Luke senses the evil within, and so, he arms himself before proceeding. Yoda, understanding the challenge before his pupil, counsels Luke to leave his weapons behind. Trusting prudence over wisdom, Luke arms himself and plunges into the cave where he is confronted by a manifestation of his nemesis, Darth Vader. Skywalker defeats his foe in a brief saber duel but his moment of victory is interrupted when Darth Vader’s mask disappears to reveal Luke’s visage.

Taking a New Approach to Syria

Much has been made of the Obama Administration’s decision to reduce the scope of its train and equip program in Syria. While the decision to dramatically overhaul the failed initiative was certainly correct, its successor seems even less likely to achieve meaningful results. Instead of discussing how best to interact with Syrian rebels, the nation should be discussing what it seeks to gain in doing so. The United States has pursued a confused and reactionary strategy in Syria that has failed to identify a clearly defined goal or objective. In order to assess how the United States can move forward in achieving its regional objectives, it must first define its end goal.

Legitimacy, Strategy, and the Islamic State

The recent wave of international terror attacks committed by the Islamic State (IS) — in Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, and France — mark a significant departure from the group’s past strategic approach. For much of its existence, most notably under the leadership of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, IS’s overriding priority has been state-building. Localized terrorism in Iraq and Syria, widely used by the organization as it transitioned from an insurgency to a proto-state, has been employed as a method of population control.

The Lessons of Hiroshima and the War Against the Islamic State

August 6th is the 70th Anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima with the Atomic Bomb that would lead to the surrender of Japan in World War II. As I consider the historical implications of the bombing, I am drawn to my discussion with my Kodokan Judo instructor, Dr. Sachio Ashida, who fought for the Japanese during World War II and ponder the implications of today’s war against the Islamic State.

#Reviewing From Deep State to Islamic State: War, Peace, and Mafiosi

Increasingly, authors are delving into the nebulous connections between autocrats, apparatchiks, and terrorists. Some have a tendency to view these connections as either the continuation of domestic politics or the instrumentalization of radicals in lieu of raising and equipping capable armies. These perspectives are heavily invested in the concept of the state — more invested in that concept than the individuals analyzed. Westerners of diverse backgrounds tend to latch on to simple narratives when seeking to explain what is really a complex and jumbled mess of motivations Misunderstanding the rise of the state security mafias could have significant consequences. Jean-Pierre Filiu has admirably attempted to correct these interpretations.

The "Islamic State" and the #FutureOfWar

Why They Are a Junior Varsity Team

When asked about the “Islamic State” last year (then referred to as ISIS), President Obama stated that, “if a jayvee team puts on Lakers uniforms that doesn’t make them Kobe Bryant.” After the Islamic State swiftly overtook Mosul and much of western Iraq last summer, media pundits and politicianscriticized the analogy. This essay argues the opposite, President Obama was absolutely correct in referring to the Islamic State as a “JV” team, and how policy makers conceptualize the world order and its threats has enormous implications for the future of war.

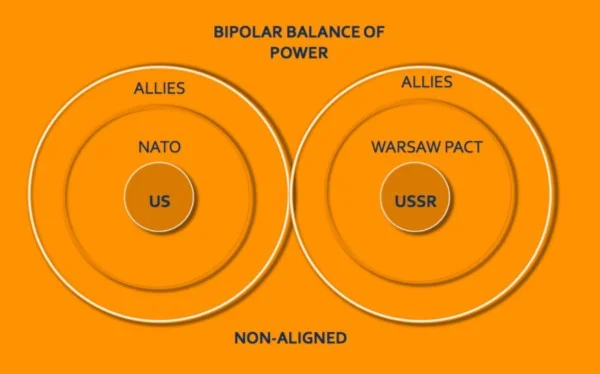

In order to conceptualize the future of war, one must understand the strategic setting (or world order). Nearly two decades ago, Barry Posen and Andrew Ross offered competing visions for U.S. national security by offering a typology for U.S. grand strategy, each with a preferred world order[1]. Instead, this essay suggests that grand strategy is not the driver of world order, but rather world order is the driver of grand strategy. Each strategic setting constructs a different type of world, with different centers of political, military, and economic power. The three scenarios in this thought experiment are: bipolarity (two antagonistic superpowers), unipolarity (one superpower) and multipolarity (multiple regional powers). These poles represent a “center of gravity” that strong nation-states generate with the weight of their economic, political and military systems.

…grand strategy is not the driver of world order, but…world order is the driver of grand strategy.

Scenario 1: Bipolar World

Neorealists such as Kenneth Waltz and Robert Art argue that the bipolar world order is the most stable. According to the neorealist literature, bipolarity tends to be the preferred world order from the U.S. security perspective because total war is unlikely between two nuclear-armed states, and only a nuclear-armed state can rise to superpower status. Instead, wars in bipolar worlds are typically proxy wars fought on the edges of hegemonic influence. The proxy wars of the Cold War, most notably the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan and the U.S. incursion into Indochina, are typical of wars fought in a bipolar world. One superpower intervenes abroad, outside their sphere of influence, and the other tries to undercut their actions. If China were to emerge as a peer competitor this century, the U.S.’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ is a logical security strategy, as most of the proxy wars with China are likely to take place in the Pacific theater of operations (but not in China itself).

Conceptualization of a Bipolar Strategic Setting

One characteristic of a bipolar world order is that it gives smaller players on the world stage an alternative to the U.S. for alignment and security assistance. For instance, during the Cold War, Egypt balanced U.S. influence by alternating between Moscow and Washington for political sponsorship, military training, monetary benefits and arms procurement. If China, or even Russia, rises to the level of a peer-competitor, “mercurial allies,” such as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) would be faced with a choice: either align with U.S. interests when seeking security assistance, or seek assistance from the other superpower.

Scenario 2: Unipolar World

The sun never set on the British Empire. (Wikispaces)

In the unipolar world, a single hegemon drives the world order, much like the Roman or British Empires did at their heights. Given the vast economic and military power of the U.S., some analysts suggest the global order for the next several decades will be unipolar. Certainly this was the general consensus after the collapse of the Soviet Union a quarter century ago. In this scenario, strategically speaking, the U.S. will have to resolve a major incongruity in the national political-military culture: distaste for imperial behavior, yet the desire to expand commercial enterprises and protect human rights abroad. Likewise, U.S. strategists will have to face an inherent paradox: every nation-state resents the hegemonic superpower, but every nation-state is seeking to become the hegemonic superpower.

The U.S. will have to resolve a major incongruity in the national political-military culture: distaste for imperial behavior, yet the desire to expand commercial enterprises and protect human rights abroad.

In this scenario, as the unipolar power, the U.S. will be called upon to intervene in regional conflicts. Without a clear national security strategy, U.S. policy makers will pick and choose battles in an ad hoc manner, administration by administration, driven by short-term political agendas. Yet, U.S. actions abroad will have unseen second and third order effects that will endure for decades and even centuries to come.

The realist would argue that as the unipolar power, the U.S. will naturally desire to retain supremacy and contain any potential peer competitors. Therefore, expansion of NATO and security of the Pacific would drive national strategy (consciously or not): NATO to contain a revisionist Russia and military presence in the Pacific to thwart Chinese aggression.

In this scenario, the U.S. can also intervene in smaller regional conflicts at will. But, what kinds of conflicts does the superpower face in a unipolar world? These are the same types of battles faced by the Roman and British Empires, and much like bipolar scenario, they will take place at the edge of the hegemonic influence. So, you can expect the U.S. to become involved in smaller regional conflicts around Russia’s borders, between Turkey and the Middle East, and around the Mediterranean and Pacific Rim.

Scenario 3: Multipolar World

In a multipolar world, there is no single superpower. Interdependence and transnational interests cloud the traditional notion of the “nation-state.” And, without strong nation-states to hold players accountable, there is a very high threat of everything from nuclear proliferation to cyber attacks from rogue organizations. Furthermore, cooperative security arrangements through multinational institutions mean priorities shift and change all over the world, all of the time.

...without strong nation-states to hold players accountable, there is a very high threat of everything from nuclear proliferation to cyber attacks…

A political realist could argue the emergence of the Islamic State today is a direct reflection of the fallout from a lopsided world order. Without Russia and the U.S. aggressively supporting the nation-state system and propping up regional powers, ungoverned spaces are left in a turbulent security vacuum. And, in an ominous foreshadowing of future events, Posen and Ross suggested “the organization of a global information system helps to connect these events by providing strategic intelligence to good guys and bad guys alike; it connects them politically by providing images of one horror after another in the living rooms of the citizens of economically advanced democracies”[ii].

According to Posen and Ross, a multipolar world begets multilateral operations. The U.S.’s contribution to military operations are typically where they have the most significant comparative advantage: aerospace power. Therefore, the future of war in a multipolar world sees the U.S. leading air campaigns against shifting enemies, mainly in failed states. Not only that, the U.S. will aggressively seek to maintain their comparative advantage in aerospace power.

Realists argue the multipolar world is the most chaotic. First, without a strong superpower to support smaller nation-states, smaller players cannot maintain a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Weak and failed states tend to spew a plethora of competing factions, some with nefarious intentions. Second, the aggressors are unclear. Some factions are supported by regional hegemons, and others are simply trying to fill the power vacuum. Finally, the U.S.’s reliance on aerospace power makes U.S. forces even more vulnerable to asymmetric attacks. The non-state actor is unlikely to strike using conventional methods, so the battlefield is cast with ambiguous players, many of which are supported by regional hegemons.

Conclusion

*Quasi-nuclear denotes states with nuclear aspirations or undeclared nuclear capability

It is difficult to discern which world order is preeminent now, but it is possible the three world orders are not mutually exclusive, nor are they static conditions. Without a doubt, the U.S. has the world’s strongest economic and military systems, which suggests they are the lone superpower. Despite this, the world is actually experiencing many of the consequences derived from a multipolar world order. This is especially prominent in the Middle East, where regional hegemons are not officially nuclear states (although several of them have the capability and will to go nuclear). So, perhaps the best way to conceptualize the world order is unipolarity in locations closest to the U.S. and elements of multipolarity in distant locations with regional hegemons. Despite their differences, unipolarity and multipolarity both suggest that the future of war will be fought on the fringes of U.S. influence, against smaller and more agile adversaries- some of which have the ability to strike the U.S. homeland, many that are getting support from a regional hegemon, and most of which are the excrescence of a failed state. This is exactly why the Islamic State is a “JV” team. At this time, the Islamic State neither has the resources nor the capability to achieve the hegemony that comes with nuclear power and projection; they are simply a satellite of a larger hegemon. The U.S.’s response to the Islamic State typifies the future of war in a multipolar world: broad coalitions and the use of aerospace power against disparate organizations.

…the future of war will be fought on the fringes of U.S. influence, against smaller and more agile adversaries…

The main issue for U.S. policy makers is not from the chaos surrounding terrorist organizations like the Islamic State. Too much time and attention has been placed on this foe while ignoring much more important issues. For instance, global conditions are going to force the Department of Defense to place the primacy on maintaining air superiority, yet many conflicts of the near future will require the techniques of agile, flexible, and rapidly-adaptable fighters. It is very important to have a force structure designed for the threats it will face. Another issue will be how the global balance of power shifts if Iran, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, or Israel becomes a declared nuclear state. If just one of these states goes nuclear (officially), it is highly likely to set off an arms race in the Middle East. More importantly, recent incursions into Crimea and Ukraine demonstrate that President Putin is intent on implementing his revisionist agenda. Given that Russia is a nuclear power and the proximity of Ukraine to NATO allies, this is the biggest threat to U.S. security interests. But, even more dramatic and uncertain will be if a non-state actor is to acquire a nuclear weapon. U.S. policy makers will no longer be dealing with a JV team if the Islamic State (or any other terrorist organization) was to obtain a “loose nuke.” To use a sports analogy, it will be the equivalent of a JV high school basketball team having LeBron James in the starting lineup: they are probably going to win a few games against older and more experienced teams.

Diane Maye is a former Air Force officer, defense industry professional, and academic. She is a PhD candidate in Political Science at George Mason University where she studies Iraqi politics. She is a proud associate member of the Military Writers Guild. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Posen, Barry and Andrew Ross. “Competing Visions for U.S. Grand Strategy” International Security 21:3 (Winter 1996/7): 6.

[2] Ibid, 25.