Looking into the future, it is critical to build more typologies for insurgent success in order to understand how states can achieve the upper hand. Most important however is conceptualizing how insurgents successfully relate their strategy of violence to their environment. Had the United States, for example, spent more time analyzing what victory looked like for the Taliban and how they planned on achieving it based on their environment, they may have bolstered America’s own strategy.

A More Talkative Place: Why the Human Domain Still Matters in Strategic Competition — #Reviewing Brutality in an Age of Human Rights

Culture and, more specifically, human terrain has not gone away with the returned focus on strategic competition. Drohan’s work highlights the tensions between moral and immoral and legal and illegal ways of seeking to defeat insurgencies as well as how governments shape and disseminate narratives that will be equally important in more conventional conflicts of the future. From winning hearts and minds to large-scale combat operations themselves, morality—indeed the whole expanse of human terrain—is just as important as lethality, not only to strategic narratives but to strategy itself.

#Reviewing War and Resistance in the Philippines, 1942-1944

Morningstar succeeds in his stated intention to “provide a basis for a fuller discussion of resistance during war as experienced in the Philippines during World War II.” As his work makes clear, localized regional insurgencies, both unified and fragmented, can coincide with and fit into larger symmetric conflicts. However, he ignores the evolution of the scholarship in elucidating the nature of asymmetric war. Specifically, he stops short of critically explaining the conflict that he otherwise ably narrates.

Strategic Drift in Afghanistan, from Bonn to the National Elections

Wars rarely follow straight paths from beginning to end. Belligerents constantly shift, seeking advantage and adapting to change, and the interaction takes its participants to places unimagined at the war's inception. Such has been the case for the American' war in Afghanistan. The U.S. started with clear strategic aims: defeat al-Qaeda and their Taliban hosts. Within months, military action had accomplished both. Yet, having achieved those aims, the war continued to escalate, and the war deviated from its expected path.

Turning Battlefield Victory Into Strategic Success: #Reviewing War and the Art of Governance

Lost Blue Helmets in Wars Among People: Revitalizing UN Peace Operations for the Context of Modern Warfare

#Reviewing Lifting the Fog of Peace

When discussing the struggles of the U.S. military in the early years of the Iraq War, Davidson uses the phrase “adapting without winning,” a formulation that surely continues to accurately describe the American experience of the post-9/11 wars. Despite the optimistic characterizations on the dust jacket that frame this book as a manual for how to succeed at counterinsurgency, though, Lifting the Fog of Peace sounds a note of caution about the gap between tactical adaptation and strategic success, even as it lauds the U.S. military for the evolution of its lesson-learning apparatus.

Fighting Irregular Wars Well

4GW is Groundless, and Here’s Why

Profound continuities have existed in warfare from the time humans first picked up heavy sticks, and any attempt to separate it into neatly delineated iterations or generations risks oversimplification. By attempting to sort military history, or any history, into neat generations, we risk overlooking points of continuity that might enhance our impressions of what “the past” must have been like.

Convergence and Governance

Public-private partnerships are crucial for success in a suppression campaign. Civil society actors can make sense of low-level contextualized problems better than the state, but the state retains more power; in partnership both gain the resource advantages of the state and the contextualization advantages of the low level actor. This partnership is contingent upon public support and upon the efficiency of the suppression regime to absorb that support.

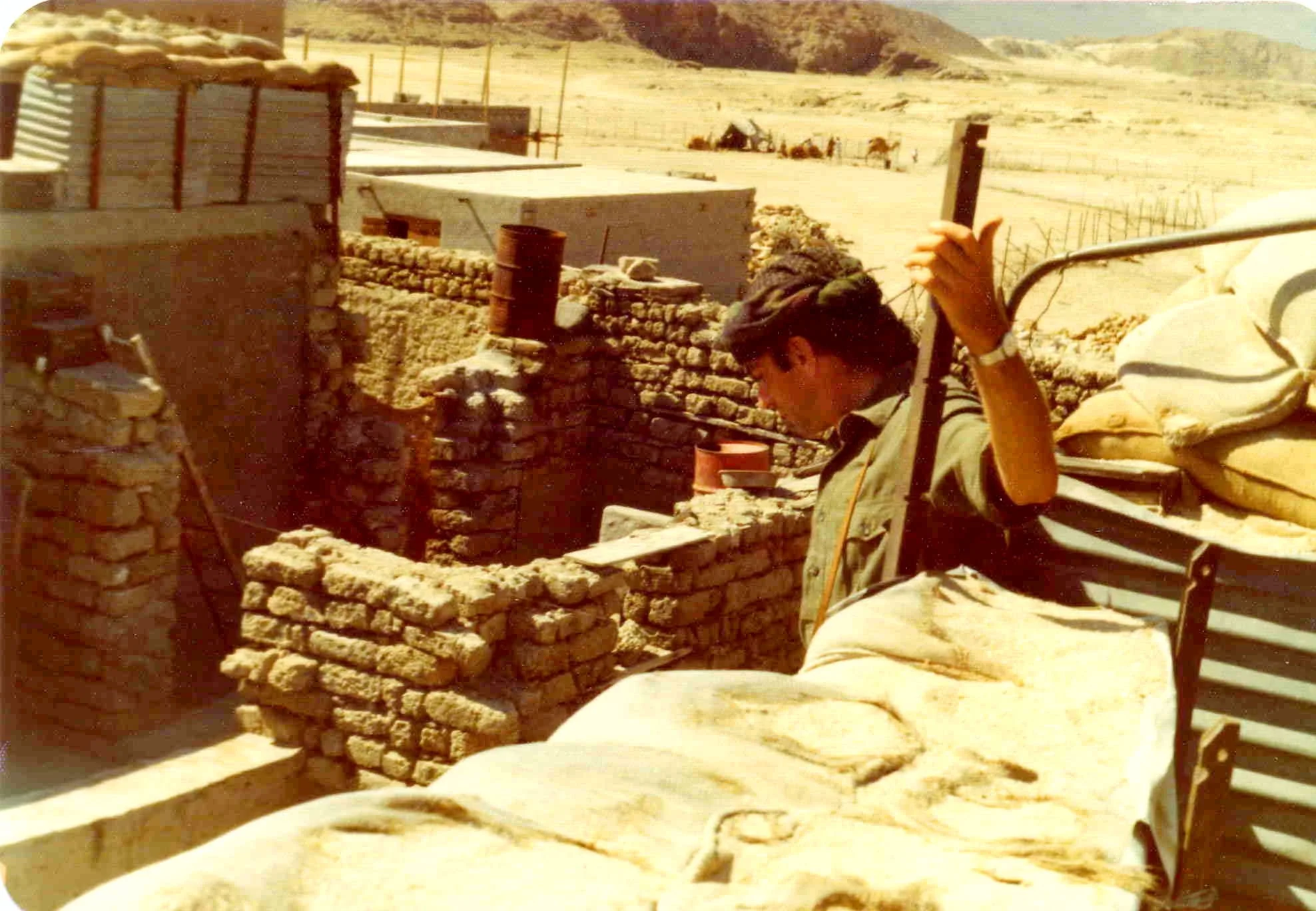

Ponder Anew: Brigadier John Graham & The Dhofar War 1970–1972

Major General John David Carew Graham CB, CBE, CStJ, Order of Oman, was born on 18 January 1923 and died on 14 December 2012 at his home on the island of Barbados. An impressive memorial service was held at St James’s Church Piccadilly on 7 March 2013, attended by hundreds of friends from both his first regiment, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and also The Parachute Regiment. This account is not an obituary, rather a study into his time in command of the Sultan’s Armed Forces (CSAF) in Oman from 1970 to 1972, a crucial period of some 18 months when the communist insurgency in Dhofar was ‘turned’.

The Oman Djebel War, 1957–59

[T]actics matter, so geography matters. Strategy is not a branch of philosophy, but a practical activity hinging on securing ground of political importance, hinging in turn on your forces beating your enemy in the physical environment concerned...Reading Seven Pillars of Wisdom will not help you in northern Oman; these are people of mountain villages, not nomads of the desert. Anyone wishing to control inner Oman from Muscat on the coast must secure these wadis, which means controlling the towns and villages along them, no mean task given the climate, their distance from the coast and that most will be fortified and held by men with local knowledge and a stake in the outcome.

War is Cruelty, and You Cannot Refine It

What do we do about the chronic, endemic issue of which ISIS is merely the latest manifestation? To answer that question, we must first look at our left and right limits of strategy and risk. What is on the table? What is off the table? What are we really trying to achieve and will it be worth the costs?The new American way of war seems to be to trickle into a fight, muddle our way through it with nebulous and often competing goals, and assume at some point—hopefully not too long after the arrival of boots on the ground or airpower overhead—that our enemies will come to their senses, lay down their arms because they suddenly see things our way, and promise to be good little citizens for time immemorial. I give you Iraq, Afghanistan, and most other every major military engagement back to Vietnam.What do we do about the chronic, endemic issue of which ISIS is merely the latest manifestation? The new American way of war seems to be to trickle into a fight, muddle our way through it with nebulous and often competing goals, and assume at some point—hopefully not too long after the arrival of boots on the ground or airpower overhead—that our enemies will come to their senses, lay down their arms because they suddenly see things our way, and promise to be good little citizens for time immemorial. I give you Iraq, Afghanistan, and most other every major military engagement back to Vietnam.

Addendum to “Learning For the Next War”

If nothing else, what our operations in Afghanistan and Iraq have taught us is that our politico-military strategies need a corresponding, overarching, dare I say, “grand” strategy. Not just guidance. Perhaps, while we are writing the immediate history of our operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, and, presumably a fresher FM 3-24, we can also include a comprehensive strategy that guides the country’s subordinate departments and agencies.

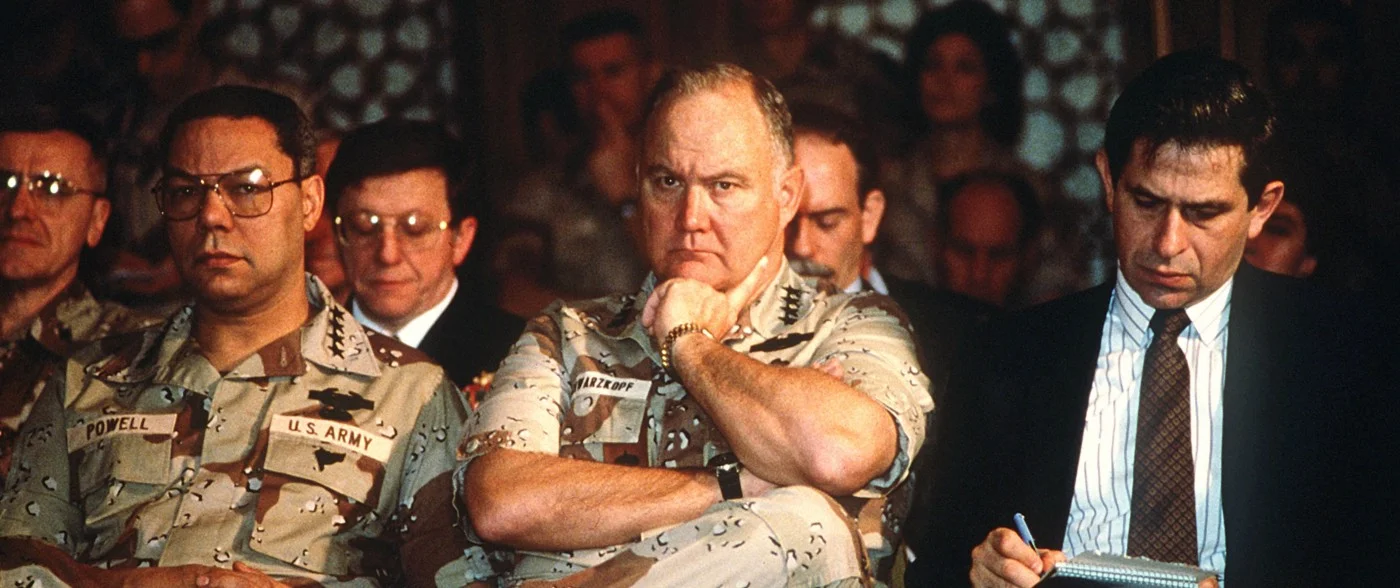

Learning for the Next War: Providing Enduring Value to the Force

Following the publication of the recent article “COIN Doctrine Under Fire,” I was lucky enough to ‘listen in’ on an enlightening conversation on one of the dozen listservs I frequent. While debating the merits of counterinsurgency, the list began discussing the value of capturing the pertinent lessons from a war…during and immediately following the conflict. On the discussion were of the authors of both the Army’s pre-eminent volume on Desert Storm and the first solid look at Iraqi Freedom.