Earlier this year, The Strategy Bridge asked university and professional military education students to participate in our fifth annual writing contest by sending us their thoughts on strategy.

Now, we are pleased to present one of the essays selected for Honorable Mention, from Craig Giorgis, a student at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies.

Introduction

Wars rarely follow straight paths from beginning to end. Belligerents constantly shift, seeking advantage and adapting to change, and the interaction takes its participants to places unimagined at the war's inception. Such has been the case for America’s war in Afghanistan. President Biden’s speech in April 2021, citing "increasingly unclear" reasons for continued American military presence, is a recognition of this fact. Many analysts and historians agree with Biden’s long-standing criticism of nation-building and counterinsurgency as a misguided prioritization of American ends and means.[1] One central theme of the Washington Post’s “Afghanistan Papers” is strategic incoherence and its long-term effects on the war.[2] Andrew Bacevich — the nation’s Cassandra regarding the limits of American power — cites the Pentagon’s “vague expectations” regarding regime change and nation-building as the root problem.[3] The U.S. started with clear strategic aims: defeat al-Qaeda and their Taliban hosts. Within months, military action had accomplished both. Yet, having achieved those aims, the war continued to escalate, and the war deviated from its expected path.

From late 2001 to 2004, American strategy drifted toward a new aim of remaking the Afghan state, not through purposeful adaptation but through a series of unintentional actions reflecting the Bush administration’s ambivalence toward nation-building. Three related interactions characterize the drift. First, the administration recognized the need to devote more attention and resources to reconstruction, driving change from the top down. Second, given ambiguous direction and without centralized leadership, tactical actions from intelligence officers, diplomats, and soldiers in Afghanistan filled the gaps in an uncoordinated and reactive strategy. Third, the U.S.’s firm commitment to Hamid Karzai pulled it into increasingly complex and expansive nation-building activities.

By better understanding how U.S. strategy changed, we better understand how war and policy interact to create circumstances unimagined at conception. To that end, this paper uses evidence from government documents and first-hand accounts to describe how strategy changed during the early post-Taliban period, from the end of the Bonn Conference in December 2001 to the Afghan national elections in October 2004. It begins with a brief chronological narrative that describes the progression toward nation-building, then examines each of the three key interactions in turn, and concludes with a few implications for strategy and policy.

Progression Toward Nation-Building: December 2001 to October 2004

The Bonn Conference of December 2001 was the start of a new, post-Taliban Afghanistan. Possibly, the most important consequence of Bonn was consensus on the interim government's chief executive: Hamid Karzai. The U.S.-Karzai relationship would shape the direction of the war in years to come. At Bonn, the U.S. relied on consensus, cooperation, and diplomacy to shape the outcome, and it intended to continue a minimalist approach to post-conflict reconstruction. In President Bush’s words, the U.S. was "not into nation-building; we're focusing on justice."[4] In late 2001, the U.S. military had about 7,000 servicemembers in Afghanistan, focused on the hunt for al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters.

Two years after the 9/11 attacks, despite the minimalist rhetoric, the U.S. was deeply committed to making a new Afghan state.

Gradually, however, America increased its military presence and nation-building activities. At the Tokyo Conference in January 2002, the U.S. committed to building an Afghan National Army. In an April speech, Bush described a "Marshall Plan" for long-term investment in Afghanistan. In November, the U.S. and its partners fielded civil-military Provincial Reconstruction Teams. The next May, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld declared an end to "major combat" and a transition "to a period of stability and stabilization and reconstruction activities.”[5]

Former U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad speaks at the inauguration of the Ghazi School in Kabul. (U.S. Department of State)

A few months later, Bush nominated Zalmay Khalilzad as Ambassador to Kabul; Khalilzad's plan, "Accelerating Success in Afghanistan," was an outline for substantial American commitment to reconstruction, and his close relationship with Karzai proved critical to its implementation. Simultaneously, Lieutenant General David Barno, commander of U.S. general purpose forces in Afghanistan, began small-scale counterinsurgency activities centered on the population — that is, an operational approach that prioritized protection of Afghans over finding and killing terrorists.[6] Meanwhile, having been confirmed as head of the interim government in June 2002, Karzai led Afghanistan through a constitutional convention in January 2004, and was subsequently elected as president of the new government in October. By the elections in late 2004, the U.S. presence had increased to about 20,000 servicemembers, with NATO allies contributing another 10,000, and their mission now included population security, Afghan security force development, and governance support.[7]

A January 2005 National Security Council assessment of U.S. strategy to date highlighted successful nation-building efforts, then indicated the U.S. would pursue additional nation-building tasks in the coming years, such as counter-narcotics and additional police training. Detailed analysis attached to the memorandum showed a multilateral effort in which the U.S. carried the preponderance of the load.[8] Indeed, the Bush administration's requested budget for reconstruction in Afghanistan increased eightfold: from less than $1 billion in 2002 to $7 billion for 2004.[9] Two years after the 9/11 attacks, despite the minimalist rhetoric, the U.S. was deeply committed to making a new Afghan state. The following sections explore the root causes behind this shift in strategy, from minimalism to commitment, by examining each of the key interactions in turn.

Top-Down Change: The Bush Administration and Nation-Building

The Bush administration’s early strategy is best described as minimalist, with Rumsfeld as its lead advocate. Many members of the administration, including Bush, had derided "nation-building" as interminable and a senseless consumption of resources. They regarded recent interventions in the Balkans as a model of what not to do: dedicate thousands of U.S. servicemembers to open-ended, multilateral peace operations. Extensive international assistance had turned the Balkans into "permanent international wards."[10] Many policymakers saw Afghanistan as especially unsuited for nation-building, being conscious of its history of resistance to foreign occupation. Peace and economic prosperity were, as a goal of American strategy, "a fool's errand."[11]

Rapid military victory over the Taliban also contributed to an underestimation of the problem of reconstruction and the resources it might require. For Rumsfeld and others, the war had "rendered military orthodoxy obsolete . . . Big and slow were out [while] lean and quick were in."[12] General Tommy Franks of U.S. Central Command assessed American arms had, in a few weeks, accomplished what the Soviets could not in a decade. In essence, Bush and his team believed that the hard work was done.[13] Some on the ground in Afghanistan shared this assessment. Though he was skeptical, when he arrived in Afghanistan in May 2002, General Stanley McChrystal commented that "it wasn't clear whether there was any war left."[14]

U.S. Army General Tommy R. Franks, Commander in Chief of U.S. Central Command, speaks to Sailors and Marines aboard USS Oak Hill (LSD 51) deployed in support of Operation Enduring Freedom Jun. 22, 2002. (U.S. Navy photo by Seaman Brandan W. Schulze)

The U.S. also sought to limit its role in providing security as well. American strategists in Washington saw public safety as an Afghan responsibility. Until the Afghans security forces could stand up, the U.S. would rely on warlords and militias to keep the peace. Initially, Rumsfeld and Franks even actively opposed expansion of the coalition military’s presence beyond Kabul.[15] In the spring of 2002, Rumsfeld's guidance to Lieutenant General Dan McNeill, then commanding U.S. forces in Afghanistan, was to kill terrorists and train the Afghan army — nothing else. He and others believed putting more U.S. soldiers on the ground would actually provoke violence.[16]

Many in the President's cabinet and among his advisors disagreed with the under-resourced minimalist approach on practical and moral grounds.

Another clear indication of Pentagon thinking is the set of cost estimates prepared in December 2001. None of the estimates accounted for humanitarian aid and reconstruction past October 2002. In planning for the next year’s budget, the White House reduced its request for security assistance and reconstruction 84 percent. Although the State Department eventually succeeded in advocating for more funding toward those areas, the estimate reflected a sense that the war was all but complete.[17]

But the Bush administration was far from monolithic. Many in the President's cabinet and among his advisors disagreed with the under-resourced minimalist approach on practical and moral grounds. Khalilzad, serving on the National Security Council at the time, noticed this divergence immediately. Although the principals were reluctant to commit, many of the deputies began to prepare and organize for reconstruction and a multilateral, long-term effort under American leadership.

Others in the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency felt the U.S. had unwisely abandoned Afghanistan after the Soviet War.

Khalilzad represented the practical position. He was "skeptical that we could prevent the re-emergence of terrorist safe havens" without extensive reconstruction, including development of liberal institutions and new security forces.[18] Others in the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency felt the U.S. had unwisely abandoned Afghanistan after the Soviet War. Marin Strmecki, special advisor to Rumsfeld, cites American strategic myopia in 1989 as a key contributing factor to the rise of al-Qaeda years later.[19]

Official portrait of Colin L. Powell as the Secretary of State of the United States of America, January 2001. (Department of State).

The second, moral position for reconstruction recognized a jus post bellum obligation to rebuild: the so-called "Pottery Barn Rule," an analogy perhaps apocryphally attributed to Colin Powell.[20] The minimalist approach was also at odds with the ideological language of the administration’s new National Security Strategy, which repeatedly emphasized the importance of liberal democracy. It also asserted liberal values as the solution to the threat posed by weak states, such as Afghanistan, and suggested the U.S. would promote those values wherever feasible.[21]

Over the next two years, a series of steps toward a strategy of nation-building reflected the increasing influence of those once-minority voices, as well as a recognition of the international community’s limited ability to support this effort. The first major step was Bush’s April 2002 speech at the Virginia Military Institute. The President warned his audience that the war in Afghanistan was not over. Peace would require not only military action, but also giving the "Afghan people the means to achieve their own aspirations," including a functional government, effective national army, broadly accessible education, and new infrastructure — in other words, nation-building assistance. He then drew an explicit connection to the Marshall Plan of post-war Europe, implying an enduring economic commitment and victory beyond that achieved through military action alone.[22] Although the administration took little immediate action — in fact, that same day, Rumsfeld assured reporters that Bush's speech did not imply large-scale peace operations[23] — the speech indicated changing attitudes.

A year later, in May 2003, Bush nominated Khalilzad as ambassador to Afghanistan; Khalilzad accepted only on the condition that the President approve a plan outlining American commitment. Khalilzad, among others, then developed what became known as the "Accelerating Success in Afghanistan" plan. Key elements included government and economic development, security force assistance, and anti-warlord activity. In June, the President endorsed Khalilzad's "Accelerating Success," and Congress approved funding in the next supplemental budget bill.

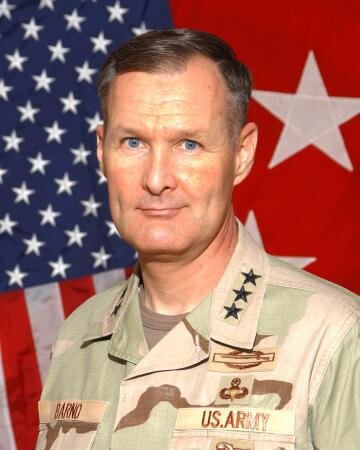

David W. Barno LTG, United States Army Commanding. (DVIDS)

Concurrent with Khalilzad's return to Kabul shortly thereafter, Lieutenant General David Barno, commander of U.S. forces, expressed his desire to conduct limited counterinsurgency operations, including partnering with nascent Afghan army forces and the deployment of Provincial Reconstruction Teams. This approach nested well with Khalilzad's; further, it implied a much broader mission set for military forces, with plenty of growth potential.[24]

The State Department supported these efforts whole-heartedly. In October 2003, State Department testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations committee — tellingly titled "Afghanistan: in Pursuit of Security and Democracy" — justified a billion-dollar supplemental funding request for an "investment" in several nation-building activities: infrastructure, schools, and governance, for example, in addition to security assistance.[25]

Senior officials at the Pentagon understood that, once committed, the effort would take many years, and would not be easily divested.

Rumsfeld, arguably the strongest voice for a minimalist approach, also changed his mind during this period. As noted above, the U.S. had committed to building an Afghan army at the January 2002 Tokyo conference. The Defense Department gradually accepted responsibility for the job. Although security assistance was traditionally the purview of the State Department, Defense had the budget, skills, and capacity for this potentially gargantuan task. In the spring of 2002, Rumsfeld acknowledged the U.S. could not withdraw until Afghanistan had the ability to provide for its own stability.

Taking responsibility for building a new Afghan National Army was a significant step away from a "light footprint" and towards an enduring commitment to nation-building. Senior officials at the Pentagon understood that, once committed, the effort would take many years, and would not be easily divested. Regardless, in July 2003, the Pentagon was committed to an Afghan National Army of up to 70,000 soldiers.[26] Rumsfeld apparently supported this effort completely. In late 2003, he issued more specific directives for development of national police, border guards, and "other security forces that exist." By April 2004, Rumsfeld was admittedly impatient with progress and open to the U.S. taking on an even greater responsibility for security force development.[27]

An Afghan National Army instructor instructs recruits at Kabul Military Training Center. (Staff Sgt. Jeff Nevison)

Rumsfeld was also open to other nation-building tasks. Unable to avert his eyes from the terrible conditions on the ground, he told the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs the U.S. "simply must provide medical attention, food, and water for the people of Afghanistan . . . It is heartbreaking."[28] In August 2002, he evinced interest in "taking the lead in some major effort" for a "highly visible" reconstruction project.[29] While the language of this particular memo is certainly not an indication of long-term investment, Rumsfeld’s subsequent actions are.

Initially, the U.S. anticipated that the U.N. would take a large post-conflict role; it already had a presence in Afghanistan, and an international effort was preferable to a large American military presence.

In a letter to the President the next day, Rumsfeld describes the "critical problem" facing the U.S. was not military but civil. U.S. efforts must therefore assist "the Karzai government to gain the resources, institutions, and strength necessary" to provide for the Afghan people — in other words, the U.S. must help build the Afghan state.[30] Concurrently, critical contributions and support to Khalilzad’s "Accelerating Success" plan came from Marin Strmecki, an influential voice in Rumsfeld’s office; the Secretary’s endorsement of the plan also indicated the Pentagon's changing attitude. [31] Rumsfeld’s attitude was clearly changing; over the course of 2002-2004, he endorsed substantive nation-building activities, welcomed international security forces, and approved significant increases to military personnel levels.[32]

Finally, the Bush administration adapted its strategy as it realized the international community was unable to shoulder the burden necessary for American minimalism to succeed. Initially, the U.S. anticipated that the U.N. would take a large post-conflict role; it already had a presence in Afghanistan, and an international effort was preferable to a large American military presence. Limited commitments at the Tokyo Conference in January 2002 reflected this attitude; U.S. contributions were only 5% of the total. [33]

Secretary of State Colin Powell, in a memorandum to Rumsfeld, acknowledged the international community was "unlikely to shoulder" the burdens of nation-building.

Within months, it was clear the administration’s expectations were unrealistic. The international community was slow to move and the requirements for reconstruction following three decades of civil war were comprehensive. U.S. Ambassador Ryan Crocker, upon his arrival in Kabul as the charge d'affaires in January 2002, found that there was "nothing to work with, no military, no police, no civil service, no functioning society."[34] The U.N. did not have the capacity for such a task. Partners who agreed to contribute nation-building efforts, such as Germany for police training, were slow, and their approach ill-suited to the conditions in Afghanistan — namely, the peculiarities of Afghan culture and the widespread destruction of their society and institutions.[35]

Secretary of State Colin Powell, in a memorandum to Rumsfeld, acknowledged the international community was "unlikely to shoulder" the burdens of nation-building. However, he argued, increasing American efforts would nevertheless align with its national interests, especially regarding security and security forces.[36] The administration adopted Powell’s recommendations, and by the end of 2004 the U.S. was shouldering most of the burden for reconstruction in Afghanistan.

Ambiguous Direction: Tactical Actions Drive a Reactive Strategy

Although the U.S. eventually adapted its strategy to include nation-building, the process was ambiguous and slow. The mixed messages described above left gaps and made for confusing national goals. For those Americans executing the strategy in Afghanistan, the problems could not wait for better guidance. Their tactical actions filled the gaps of an uncoordinated, reactive, and often inattentive strategy. They thus established, or at least influenced, national goals from the bottom up and committed the U.S. piecemeal to increased nation-building responsibilities.

Bureaucratic politics and organizational parochialism are unavoidable facts of strategy. As they have in many other wars, in Afghanistan, they conspired against unity of effort and clarity of purpose. In its first term, the Bush administration was especially polarized around strong personalities, such as Powell, Rumsfeld, Vice President Dick Cheney, and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice. Those principal leaders failed to reconcile their differences, and the administration thus struggled to develop and adapt its strategy.[37]

The problem of clear strategic guidance was further exacerbated by the paucity of attention paid to Afghanistan by the administration throughout and especially after it shifted attention to Iraq in 2002.

Moreover, the administration established no single authority for American strategy or for reconstruction. Nor was there a single authority for U.S. operations on the ground in those years; the embassy, the C.I.A., conventional forces, and special operations forces each reported to their own chain of command.[38] Confusion was endemic. Nine months into the war, Rumsfeld expressed some bewilderment regarding various U.S. agencies' activities, for example, requesting his staff answer very basic questions regarding support to Karzai and various warlords by the State Department, C.I.A., and the Defense Department .[39]

The problem of clear strategic guidance was further exacerbated by the paucity of attention paid to Afghanistan by the administration throughout and especially after it shifted attention to Iraq in 2002. In October 2002, on Rumsfeld’s advice, the President declined to meet with General McNeill, demonstrating the war's low priority.[40] In 2003, the National Security Council met only twice to discuss Afghanistan.[41]

Disunity and inattention resulted in unclear objectives for those assigned to execute America’s post-Taliban strategy. Regardless, the opportunities for reconstruction were obvious to Americans on the ground. Sarah Chayes, a journalist and aid worker, described Kandahar immediately following the fall of the Taliban as chaotic and ruined and yet still hopeful of American help. She was mystified by the American military's reluctance to commit to reconstruction, and discouraged by the obviously uncoordinated efforts of conventional forces, special operations forces, and other agencies like USAID. Without a "clear notion of what the desired endstate” was, efforts were "slipshod and haphazard."[42] General McNeill admitted as much: "There was no campaign plan in early days, in 2002.”[43]

When the purpose is unclear, or not commonly understood by the various agencies involved, those closer to the problem do what they think best.

Chayes came to the same conclusion as many others regarding the lack of coherent strategy. Tactical organizations filled in the gaps as best they could, and advocated for increased resources.[44] Barno and other senior leaders, in turn, requested for more soldiers to conduct counterinsurgency and reconstruction — more support to Provincial Reconstruction Teams, for example.[45] Steve Coll describes a pattern of engagement typical of American action in Afghanistan: "deliberate minimalism, followed by tentative engagement, followed by massive investment,"[46] each step potentially pulling the U.S. into further commitments.

When the purpose is unclear, or not commonly understood by the various agencies involved, those closer to the problem do what they think best. Since the problem of unity was never adequately addressed during this period, strong and effective personalities on the ground had an outsized effect on the path American strategy took. In the case of Khalilzad and Barno — especially given their close relationship — these changes moved the U.S. toward a nation-building strategy supported by a military counterinsurgency campaign.

Commitment to Karzai Pulls the U.S. Toward Nation-Building

Khalilzad's close relationship with Karzai was also critical to the path of American strategy. In December 2001, Karzai was the keystone to the Bonn Agreement. By the time the Afghan electorate voted him president in October 2004, the U.S. was firmly invested in his continued success. In turn Karzai’s success depended on the assistance he could extract from the U.S., Khalilzad was central to this process throughout. His actions were critical first to Karzai's ascension to power and then in binding American goals to Karzai's success.

Afghan President Hamid Karzai gestures with a Pentagon tea cup in his hand as he offers a brief cultural exchange on tea etiquette in his country to U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta during a working luncheon at the Pentagon in Arlington, Va., Jan. 10, 2013. (DoD photo by Glenn Fawcett/Released)

Khalilzad, an Afghan Pashtun by birth, having since been educated in the U.S. and subsequently serving in previous Republican administrations, was an obvious choice to help the new Bush administration develop policy for Afghanistan. In September 2001, he was serving in the National Security Council. Soon thereafter, President Bush appointed him Special Envoy and then Ambassador to Afghanistan. Khalilzad's proven record of long service to Republican administrations made him a trusted agent of the White House; this close connection with the President and National Security Council was a powerful tool for his advocacy. Indeed, Khalilzad's tenure as special envoy and ambassador was concurrent with a sharp increase in U.S. commitment to security and nation-building.[47]

Additionally, Khalilzad’s assistance at Bonn was important to its success and the consensus around Karzai. As an interim leader, Hamid Karzai was a compromise acceptable to all of the relevant parties. His status as a Durrani Pashtun, from which many historical Afghan leaders had come, enhanced his legitimacy. Additionally, the various ethnic factions of the anti-Taliban alliance appreciated Karzai's potential to work with the international community. The international community was likewise willing to work with Karzai, to the extent that even rival Iranian and Pakistani administrations supported his ascension to lead the interim government in late 2001. Indeed, without these two countries' support, the interim government was unlikely to succeed.[48]

Once both Karzai and Khalilzad were established in Kabul, the American ambassador was not shy in exercising his power to shape Afghan politics and "often better resembled a proconsul than a diplomat."[49] Khalilzad met with Karzai almost daily, working both overtly and discreetly to solidify his control over the still-nascent fractious Afghan government. As envoy and ambassador, his success was indistinguishable from the new Afghan leader’s. In Karzai, Khalilzad saw a leader capable of uniting the factions and delivering good governance, first as an antidote to the poison of warlordism, "the most persistent challenge" of the post-Taliban period. Khalilzad thus intervened in the emergency Loya Jirga of 2002 to ensure the Afghan royal family did not impede Karzai's ascendency, personally persuading various factions and delegations to support Karzai.[50]

Khalilzad also encouraged Karzai to develop relationships with key members of the Bush administration. Washington proved receptive to his overtures, and Karzai alternately requested, demanded, or implored the U.S. for nation-building resources and activity. Upon assuming his role at the head of the interim government, he immediately requested international troops for Afghanistan's cities. In mid-2002, Karzai flew to the U.S. to meet with President Bush and request aid for massive reconstruction projects, such as the road between Kabul and Kandahar — key political terrain for Afghan governance. Bush agreed to help. In the fall of 2002, Karzai and his finance minister, Ashraf Ghani, again pleaded for U.S. financial assistance on a variety of fronts: border police, civil servants, basic services, and economic development.[51] Karzai even managed to influence Rumsfeld, a bulwark of minimalism.

It soon became clear to U.S. leaders in Washington and Kabul that Karzai had his own interests and plans, many of which were at odds with their initial, minimalist strategy.

After a visit to Kabul in April 2003, Rumsfeld directed a planning exercise at the Pentagon. Ideas from this exercise were incorporated into "Accelerating Success," indicating the Pentagon’s increasing appetite for reconstruction in Afghanistan.[52] More importantly, Bush’s relationship with Karzai continued to be close; the president spoke to him frequently and genuinely believed the best way to influence Karzai was through friendship and mutual respect.[53]

It soon became clear to U.S. leaders in Washington and Kabul that Karzai had his own interests and plans, many of which were at odds with their initial, minimalist strategy. Karzai, following a centuries-long pattern of Afghan rulers, sought foreign aid to strengthen his regime as well as improve the plight of his people. Khalilzad, too, understood that many Afghans, especially the political elite, supported American involvement. He noted the delegates to the Constitutional Loya Jirga of December 2003 clearly expected that the international community, led by the U.S., would provide long-term assistance. However, as foreign soldiers can elicit resentment simply by their presence — the so-called "antibody" problem — overt U.S. support for Karzai detracted from his legitimacy, and ultimately encouraged him to distance himself from American interests publicly. This fracture was, however, years in the future; in the immediate post-Taliban period, Karzai and the Bush administration were tightly intertwined. Since U.S. success was vested in Karzai's success, the strategy changed, gradually incorporating nation-building activities. By the time of Karzai's election in October 2004, the U.S. was leading what would become a massive nation-building effort.

Implications for Strategy and Policy

Establishing definitive historical causality is difficult. Though the above three factors are important, they are therefore only a partial explanation. Many other factors shaped American strategy during this critical period. Nonetheless, this examination is instructive as a case study in post-conflict responsibility. What would have happened had the U.S. stuck with its initial, minimalist approach? Given historical hindsight, we can only conclude that the Taliban resurgence of the mid-2000s would have come earlier, prompting either a U.S. withdrawal or re-invigorated effort. Additionally, given the pervasive overconfidence that characterized the early Bush administration, it is difficult to imagine it directing a strategy that recognized the unpredictability of war and the limits of American power. In other words, choosing a strategy of limited aims and compromise — i.e., “counterterrorism plus,” as advocated by Biden years later — was simply not politically realistic in 2002.

From 2002-2003, a minimalist approach to training Afghan security forces resulted in almost no progress.

Therefore, a more reasonable and useful counterfactual imagines a strategic path in which the U.S., committed to the ideology of the 2002 National Security Strategy, prepared for long-term investment from the start. As it happened, the Bush administrations' early ambivalence — minimalist avoidance to commitment on one hand, maximalist desire to remake Afghanistan on the other — resulted in a failure to develop a coherent strategy in the immediate aftermath of the Taliban. The U.S. delayed important investment in the Afghan government, economy, and military. From 2002-2003, a minimalist approach to training Afghan security forces resulted in almost no progress. Money was spent, soldiers were trained and equipped, but the Afghan army failed to grow accordingly; the U.S. had lost a year of effort. Further, the minimalist approach not only failed to address the problems associated with warlordism, its prioritization of short-term interests also strengthened the rapacity of warlords at the expense of long-term governance and the welfare of the Afghan people.

Although American strategy eventually attempted to address both of these problems, the delay was costly. In 2005, a reconstituted Taliban exploited the lack of security and social grievances caused by warlordism. Simply put, by denying the impetus to nation-building, the U.S. missed a series of opportunities to consolidate their initial victory and set conditions for enduring stability in Afghanistan.[54]

An early commitment to nation-building was both reasonable and feasible for the Bush administration in 2002-2003. Because of its clear ties to 9/11, it enjoyed wide domestic and international support for the war in Afghanistan. In the Balkans, it had successful models to replicate, although the results of these peace operations were far less clear in 2001 than they are today. And the "Rumsfeldian" resistance to nation-building was not as black-and-white as the rhetoric might indicate. Rumsfeld's changing perspective was indicative of other minimalists. Incrementally, they realized both the extent of the devastation in Afghanistan and the limited capacity of the international community required a larger American commitment.

Regardless of the changing perspective, the initial strategy lacked clarity. Crystal-clear policy aims are a strategic chimera, despite the imperative of the Powell Doctrine. Strategy is a practical exercise; good ideas bump up against the reality of partisan compromise, ideology, and the limits of power. However, it is reasonable to expect something more than simply negative policy aims — i.e., that the U.S. would not conduct nation-building and peace operations. Refusing to commit is not a substantive policy. Given this ambiguity and the subsequent mixed messages regarding U.S. intent, bureaucrats and soldiers "made different assumptions about the role we would play", in Khalilzad's words, and changed U.S. strategy accordingly.[55]

Finally, early success led to hubris: victory came quickly, in Kabul and in Bonn, and it was intoxicating. The euphoria changed risk tolerances and created expectations for further success using a minimum of resources. Overconfident policymakers thus declared victory prematurely and trivialized the difficulty of the tasks ahead.[56] Rumsfeld, among many others in the administration, was particularly susceptible to belief in the durability of early success, delivered as promised by the so-called "Revolution of Military Affairs" and military "transformation” — concepts which promised quick, decisive victory. Indeed, the eagerness to believe in such concepts should be one of the most important implications of the American experience in Afghanistan. U.S. strategy should recognize that war changes policy aims, and every short war has the possibility of becoming a long one.

Craig Giorgis is an officer in the United States Marine Corps. He wrote this paper while studying in the Secretary of Defense Strategic Thinkers Program at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, February 2002 (R. D. Ward).

Notes:

[1] The White House, “Remarks by President Biden on the Way Forward in Afghanistan,” 14 April 2021,

www.whitehouse.gov/; Marc Ambinder, “Biden, on the Afghanistan Debate, in His Own Words,” The Atlantic, 3 August 2010; Council on Foreign Relations, “Candidates Answer CFR’s Questions,” 1 August 2019, https://www.cfr.org/article/joe-biden.

[2] Craig Whitlock, “Built to Fail,” Washington Post, 9 December 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-nation-building/.

[3] Andrew Bacevich, “The American defeat in Afghanistan”, Los Angeles Times, 4 March 2020.

[4] George Bush, quoted in Zalmay Khalilzad, The Envoy, 5th Ed. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2015), 139.

[5] Vernon Loeb, "Rumsfeld Announces end of Afghan Combat," Washington Post, 2 May 2003.

[6] Steve Coll, Directorate S: The CIA and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan (New York: Penguin Books, 2018), 185, 193, 205.

[7] Ian Livingston and Michael O'Hanlon, "Afghanistan Index", Brookings, 30 September 2012; Thomas Barfield, Afghanistan (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 313-314.

[8] Condoleezza Rice, " 'Accelerating Success in Afghanistan' in 2004: An Assessment", National Security Council, 18 January 2005, https://papers.rumsfeld.com/library/.

[9] Dov S. Zakheim, A Vulcan's Tale (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2011), 189.

[10] James Dobbins, After the Taliban: Nation-Building in Afghanistan (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2008), 27-8, 124, 164.

[11] Rumsfeld, quoted in Coll, Directorate S, 183.

[12] Andrew Bacevich, America's War for the Greater Middle East (New York: Random House, 2016), 231.

[13] Khalilzad, The Envoy, 116; Dobbins, After the Taliban, 30, 134.

[14] Stanley McChrystal, My Share of the Task (New York: Penguin, 2013), 77.

[15] Dobbins, After the Taliban, 85, 103, 125.

[16] Coll, Directorate S, 134-35.

[17] Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale, 144, 168-69.

[18] Khalilzad, The Envoy, 115, 139, 149-50.

[19] Coll, Directorate S, 129-30; Dobbins, After the Taliban, 6; Marin Strmecki, interview by Candace Rondeaux, 2, 19 October 2015, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/.

[20]He denies using the term, but affirms he supported the idea, and emphasized the point prior to the invasion of Iraq in 2003; see "Ideas and Consequences", The Atlantic Monthly, October 2007.

[21] The White House, “National Security Strategy”, 17 September 2002, https://2009-2017.state.gov/.

[22] George Bush, "President Outlines War Effort," 17 April 2002, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/.

[23] James Dao, "Bush Sets Role for U.S. in Afghan Rebuilding," New York Times, 18 April 2002; Dobbins, After the Taliban, 135.

[24] Khalilzad, The Envoy, 177, 179, 181, 187; Strmecki, 11.

[25] Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Afghanistan: In Pursuit of Security and Democracy, 108th Congress, 1st. sess., 2003, 38.

[26] Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale, 139-140; Khalilzad, The Envoy, 182.

[27] Donald Rumsfeld, Memorandum to Dough Feith, 17 April 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/ ; Memorandum to General John Abizaid, 19 December 2003, https://papers.rumsfeld.com/library/; Memorandum to General Dick Myers, et al., 7 April 2004, https://papers.rumsfeld.com/library/.

[28] Donald Rumsfeld, Memorandum to General Dick Myers, 8 November 2001, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/.

[29] Donald Rumsfeld, Memorandum to Dov Zakheim, 19 August 2002, from Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale, 169.

[30] Donald Rumsfeld, Memo to the President, 20 August 2002, https://papers.rumsfeld.com/library/.

[31] Strmecki, 4.

[32] Dobbins, After the Taliban, 165.

[33] Ibid., 23-5, 122-123; Coll, Directorate S, 129.

[34] Ryan Crocker, interview by Candace Rondeaux, et al., 11 January 2016, 9, SIGAR, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/.

[35] Robert Finn, interview by Candace Rondeaux, 22 October 2015, 8, SIGAR, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/.

[36] Colin Powell, Memorandum to Donald Rumsfeld, 16 April 2002, https://papers.rumsfeld.com/library/; Strmecki, 3.

[37] Hew Strachan, Direction of War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 92; for more direct evidence, though relating to the Iraq War, see Thomas Andrews Sayle, et al., eds., The Last Card (New York: Cornell University Press, 2019), 314-27.

[38] Ryan Crocker, interview by Greg Bauer and Deborah Scroggins, 1 December 2016, 11, SIGAR, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/; Zakheim, 174, 266.

[39] Donald Rumsfeld, Memorandum to Doug Feith, 26 June 2002, https://papers.rumsfeld.com/library/.

[40] Donald Rumsfeld, Memorandum, 21 October, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/.

[41] Coll, Directorate S, 145.

[42] Sarah Chayes, The Punishment of Virtue (New York: Penguin, 2006), 106-7, 151.

[43] Dan McNeill, interview by Paul Kane, undated, 4,SIGAR, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/afghanistan-papers/afghanistan-war-confidential-documents/.

[44] Chayes, Punishment of Virtue, 155, 274.

[45] Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale, 210.

[46] Coll, Directorate S, 192.

[47] Dobbins, After the Taliban, 118.

[48] Ibid., 57, 74, 89; Barfield, Afghanistan, 290-92; Khalilzad, The Envoy, 129-21.

[49] Barfield, Afghanistan, 310.

[50] Khalilzad, The Envoy, 136-37, 144-45, 191; Barfield, Afghanistan, 297.

[51] Dobbins, After the Taliban, 105; Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale, 178; Khalilzad, The Envoy, 131, 194; Bacevich, America’s War, 230.

[52] Coll, Directorate S, 185-86.

[53] Khalilzad, The Envoy, 199; Coll, Directorate S, 132, Sayle, Last Card, 72-3.

[54] Dobbins, After the Taliban, 138; Strmecki, 7; Zakheim, A Vulcan’s Tale, 37, 277.

[55] Khalilzad, The Envoy, 115.

[56] Bacevich, America’s War, 224; see also Dobbins, After the Taliban, viii.