Preparing for future warfare based on historical lessons has long been fundamental to military leadership and strategy. Napoleon’s study of history and march on Moscow illustrate why even the most assiduous students of history often follow their predecessors into disaster.

Logic and Grammar: Clausewitz and the Language of War

Clausewitz’s concepts of grammar and logic have stood the test of time. His dictum that war is indeed “the continuation of policy by other means” holds true today, and while the character of war has evolved, the higher logic and the influence of policy has remained a constant. This article will first address some key definitions, before exploring the concept of logic and grammar as introduced in On War and as they relate to his own experiences. These concepts will then be explored through the prisms of two contrasting case studies: industrialised warfare on the Western Front during the First World War, and the new logic of war in the face of the unprecedented existential threat of the Nuclear Age.

From Blind Cyclops to Well-Tuned Machine: #Reviewing Spying for Wellington

This detailed study of the intelligence function will prove especially useful to those studying the conduct of intelligence operations throughout the era, whether on the Iberian Peninsula or elsewhere. Davies has also added to the body of knowledge about the Duke of Wellington himself. We get a better appreciation for how Wellington balanced the collected intelligence with his own senses to reach the decisions that propelled him to defeat the French forces in Iberia, and then again with Prussian assistance at Waterloo. Overall, Huw Davies has made an important contribution to the historiography of the Napoleonic field.

Why the Military is the Wrong Tool for Defending Western Society

Napoleon’s advantage was created by a change in the sociopolitical environment. It could be argued a similar change in the nature of society and politics has been occurring in the West in the period since World War I. The more recent sociopolitical change occurred among the Western industrial nations over the last century and involved a shift towards individualism. It allowed liberal democracy to become the standard form of Western government. It created a New World Order that allowed for organizations like the EU that would have been unheard of in nineteenth-century Europe.

Introducing #Scharnhorst: On the Nature of Leadership in War and the Role of Socio-Political Conditions

For modern readers, the fear Napoleon and his victories struck into the hearts of European monarchs and generals is inconceivable…Not everyone saw Napoleon as a military genius beyond human explanation, however. Scharnhorst admired his understanding of the social and political changes wrought by the French Revolution and his ability to apply these changes to warfare. Nonetheless, Scharnhorst believed Napoleon’s success harbored clues about his possible defeat.

#Reviewing Titan: The Art of British Power in the Age of Revolution and Napoleon

The titanic struggle between Britain and France (and their respective allies) has been told many times, but the narrow focus here on Britain’s use of power is a welcome addition indeed, and Titan builds a compelling case for what made British victory possible. It will certainly prove useful to strategists and foreign policy practitioners, for while much has changed in the realm of war and diplomacy since the early nineteenth century, the need for smart power will not be ending anytime soon.

Lombardi’s War: Formation Play-Calling and the Intellectual Property Ecology

The information age, a phrase famously coined by Berkeley Professor Manuel Castells in the 1990s, described a tectonic shift in our culture and economy which we generally take for granted at present. From our current vantage point, replete with ubiquitous pocket-sized personal computing and communications devices, it is hard to imagine a world where we cannot convert our data or social networks into physical resources and access. We keep our data in the cloud and call upon it when we need it, regardless of where we are. We log into AirBnB, and somehow money we have never seen transfers to someone else who will never see the money, and that becomes a room for an evening. The idea of a brick-and-mortar video store, such as the 1990s-staple Blockbuster Video, is hopelessly anachronistic in the era of Netflix.

Modelez-Vous: Deriving Frameworks From History

It is oft quoted in numerous aphorisms and proverbs that we should learn from the past. According to Napoléon Bonaparte’s last maxim, in his Maximes de Guerre de Napoléon, one should “Lisez, relisez les campagnes d’Alexandre, Annibal, César, Gustave, Turenne, Eugène, et de Frédéric; modelez-vous sur eux; voilà le seul moyen de devenir grand capitaine, et de surprendre les secrets de l’art de la guerre” [“Read, reread the campaigns of Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Julius Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Vicomte of Turenne, Prince Eugene of Savoy and Frederick the Great; model yourself on them; that there is the only way to become a great commander, and to obtain the secrets of the art of war.”]

Moving Beyond Mechanical Metaphors: Debunking the Applicability of Centers of Gravity in 21st Century Warfare

As many historians like to point out, 19th century Prussian military theorist and army officer Carl von Clausewitz’s (1780-1831) seminal work, On War, was not written to be a “how-to” manual about waging warfare, but instead as a timeless treatise on the nature of war. Yet, Clausewitz was a product of both his time and experience. As a result, some of the ideas and metaphors Clausewitz used to describe his understanding of war and warfare might have outlived their utility. This is certainly not to say On War or Clausewitzian theory no longer carries value, but instead suggests some of the concepts therein need reexamined in relation to the passing of time. One of Clausewitz’s more controversial concepts, the center of gravity, falls into this category. The center of gravity (COG) – a metaphor to define warfare between relatively closed systems – has been rendered ineffective in modern warfare. Modern warfare is embodied by the collision of opposing systems in pursuit of political objectives. Modern systems sense, adapt, and act, while simultaneously hiding and protecting their critical vulnerabilities, and operating for self-perpetuation. Doctrine, rooted in a linear, Jominian application of Clausewitz’s COG concept, lacks the agility – cognitive and physical – to match the dynamism of contemporary systems warfare. As a result, doctrine must break with an anachronistic application of a metaphor, which is suited for 18th and 19th century warfare, and instead address the realities of contemporary and future warfare by replacing the COG with a systems approach that accounts for an adversarial systems’ ability to sense, adapt, and act. In doing so, doctrine will become more responsive to the fleeting opportunities in warfare, resulting in a more meaningful use of force.

Five Things That Helped Carl von Clausewitz Become A Great Strategic Thinker

While Carl von Clausewitz is often quoted, in reality his treatise On War is rarely studied in depth. In times when the U.S. military struggles to find its strategic footing, however, reading and debating Clausewitz’s complex ideas are needed more now than ever before. Perhaps even the times and conditions in which he developed them deserve a second look, for they contain lessons about how strategic thinkers grow and develop.

Applying Jomini to the Ukrainian Donbas Conflict

Looking at the current situation on the ground for the Ukrainian military, Henri Jomini and his work The Art of War provides not only a framework for analyzing the conflict at the campaign level, but also for providing a guide to the Ukrainian military in its effort to defeat the two separatist republics. Jomini’s core principles include offensive, rather than defensive, action, as well as massing forces at a decisive point of attack to gain local superiority. His magnum opus elaborates on these principles and their application, often applying geometric concepts and terms to battlefields and theaters of war for explanations.

The Threatening Space Between Napoleon and Nukes: Clausewitz vs. Schelling

Great theories stand the test of time—shedding light on their subject’s essence despite varying contexts, technological upheavals or mutable human relations. One such work is Carl von Clausewitz’s On War. That said, with the detonation of the atomic bomb and the proliferation of nuclear weapons, many find Clausewitz wanting. How can there be a decisive battle without nuclear annihilation? Nuclear weapons seem to breach our understanding of force, suggesting the need for radically different conceptions of war. Enter Thomas C. Schelling and his work on The Strategy of Conflict

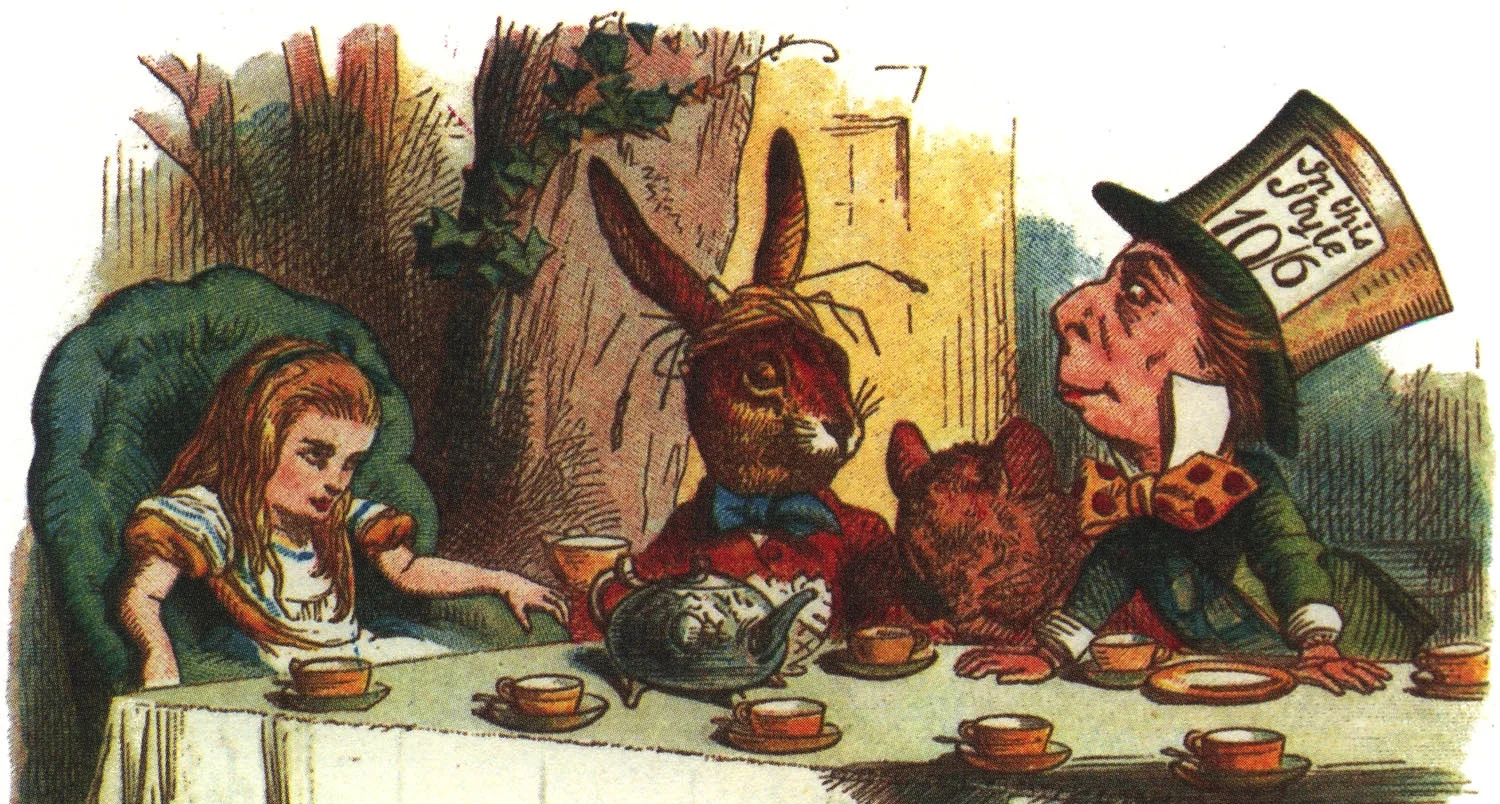

Down the Rabbit Hole: Alice and the Experience of Clausewitzian Genius

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland can help us better understand the experience of Clausewitzian genius. Now, this sounds about as illogical as Lewis Carroll’s famous riddle, uttered by the Mad Hatter: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” But unlike the riddle, which was initially constructed without an answer, the concept of genius links Clausewitz and Alice without artifice. While Clausewitz’s “field of genius...raises itself above rules,” Wonderland is a fantastical space that enables Alice to raise herself not only above rules, but also sense. To see how this is so, we can appeal to Alice and her encounters in Wonderland to highlight the complexity found within military genius. But first we must locate genius in the space where theory fails to map onto reality.