Students of Clausewitz now have a new and exciting source of information. Scholars from his home town recently discovered Marie von Clausewitz’s last will and testament. One of the most remarkable finds is eleven pages containing a catalogue of the 380 volumes in the library of Carl and Marie.

The Relevance of Clausewitz and Kautilya in Counterinsurgency Operations

The operational and doctrinal relevance of Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Clausewitz’s On War in today’s counterinsurgency operations remains firm and valid. In numerous instances, they provide us a template to analyze various aspects of a counter-insurgency operation including the use of local values and principles as a tool to understand the strategic culture of an adversary. It must be understood that the evolution of technology may improve one or other aspects of a counterinsurgency operation, but the core elements remain more or less the same and are diverse depending upon the region of conflict. The non-linearity and flexibility of an insurgency are such that it can exploit various means such as misinformation campaigns, religious and ideological differences, as well as enlisting foreign support to keep it alive during the conflict.

The Rock and Mortar of the Strategy Bridge: #Reviewing On Tactics

Friedman intentionally authored a quick read, believing the work should fit in a leader’s cargo pocket, and he strikes the perfect balance between brevity and gravity. Beyond the main effort of introducing an outline of tactical tenets and concepts, Friedman’s work also introduces strategic titans to the new tactician. This foreshadowing is an invaluable secondary benefit, as it creates scaffolding for later exploration in leaders yet unexposed to these thinkers. One could be excused for thinking Friedman’s work might lose coherence through the frequent calling forth of these tactical and strategic visionaries, but he altogether avoids the trap of confusing the narrative and masterfully weaves a tapestry of their individual thoughts that surgically and powerfully complement his work.

Disruption in the Trinity

Scholars of Clausewitz have gone to great pains to distinguish and connect the primary trinity of passion, chance, and reason with the secondary trinity of people, military, and government. In repudiating the Powell Doctrine’s focus on only the secondary trinity, Hew Strachan points out the the triad of people, military, and government are the “application” of the trinity—they are elements of the “state, not of war.” But for Antulio Echevarria, an equally erroneous position would be to ignore the secondary trinity, as he argues Clausewitz was clear in drawing the connection between the intrinsic and the institutional. In taking a position diametrically opposed to van Creveld, Echevarria suggests we risk divorcing Clausewitz from the “practical concerns of the debates of his day.”

Fighting in Three Realms: Democratic, Autocratic, and Ideological

The political nature of the combatants changes the character of the war being fought. It starts with the idea that wars are different based on the type of political organization fighting the war. Democracies fight wars differently than autocracies, which fight wars differently than theocracies. The political nature of each of these types of government offer both strengths and weaknesses during the campaign. To develop a complete strategy the military and political leadership must take these differences into account.

The Wages of War Without Strategy

In this––our final installment––we appeal to each element of the Clausewitzian Trinity to do its part. To remain silent as practitioners of policy and war, we believe, would perpetuate the betrayal of those troops and civilians––American and foreign––who have made the ultimate sacrifice for reasons this country still struggles to articulate.

The Wages of War Without Strategy

War and violence decoupled from strategy and policy—or worse yet, mistaken for strategy and policy—have contributed to perpetual war, or what has seemed like 15 years of “Groundhog War.” In its wars since 11 September 2001, the United States has arguably cultivated the best-equipped, most capable, and fully seasoned combat forces in remembered history. They attack, kill, capture, and win battles with great nimbleness and strength. But absent strategy, these victories are fleeting. Divorced from political objectives, successful tactics are without meaning.

Moving Beyond Mechanical Metaphors: Debunking the Applicability of Centers of Gravity in 21st Century Warfare

As many historians like to point out, 19th century Prussian military theorist and army officer Carl von Clausewitz’s (1780-1831) seminal work, On War, was not written to be a “how-to” manual about waging warfare, but instead as a timeless treatise on the nature of war. Yet, Clausewitz was a product of both his time and experience. As a result, some of the ideas and metaphors Clausewitz used to describe his understanding of war and warfare might have outlived their utility. This is certainly not to say On War or Clausewitzian theory no longer carries value, but instead suggests some of the concepts therein need reexamined in relation to the passing of time. One of Clausewitz’s more controversial concepts, the center of gravity, falls into this category. The center of gravity (COG) – a metaphor to define warfare between relatively closed systems – has been rendered ineffective in modern warfare. Modern warfare is embodied by the collision of opposing systems in pursuit of political objectives. Modern systems sense, adapt, and act, while simultaneously hiding and protecting their critical vulnerabilities, and operating for self-perpetuation. Doctrine, rooted in a linear, Jominian application of Clausewitz’s COG concept, lacks the agility – cognitive and physical – to match the dynamism of contemporary systems warfare. As a result, doctrine must break with an anachronistic application of a metaphor, which is suited for 18th and 19th century warfare, and instead address the realities of contemporary and future warfare by replacing the COG with a systems approach that accounts for an adversarial systems’ ability to sense, adapt, and act. In doing so, doctrine will become more responsive to the fleeting opportunities in warfare, resulting in a more meaningful use of force.

Five Things That Helped Carl von Clausewitz Become A Great Strategic Thinker

While Carl von Clausewitz is often quoted, in reality his treatise On War is rarely studied in depth. In times when the U.S. military struggles to find its strategic footing, however, reading and debating Clausewitz’s complex ideas are needed more now than ever before. Perhaps even the times and conditions in which he developed them deserve a second look, for they contain lessons about how strategic thinkers grow and develop.

In the Mind of the Enemy: Psychology, #Wargames, and the Duel

Over the last eighteen months, the Australian podcast the Dead Prussian has asked each of its guests a simple yet deeply contested question: “What is war?” Answers have ranged from Professor Hal Brand’s insightful “war is a tragic but inescapable aspect of international politics” to my own citation of John Keegan’s “war is collective killing for some collective purpose.”Nobody so far has said that war is a “game”. Thankfully this isn’t surprising; anyone who has fought in war, or just studied it, will be aware that this would trivialise the destruction that can lie within. But it is also of note that nobody so far has labeled war as a duel.

The Threatening Space Between Napoleon and Nukes: Clausewitz vs. Schelling

Great theories stand the test of time—shedding light on their subject’s essence despite varying contexts, technological upheavals or mutable human relations. One such work is Carl von Clausewitz’s On War. That said, with the detonation of the atomic bomb and the proliferation of nuclear weapons, many find Clausewitz wanting. How can there be a decisive battle without nuclear annihilation? Nuclear weapons seem to breach our understanding of force, suggesting the need for radically different conceptions of war. Enter Thomas C. Schelling and his work on The Strategy of Conflict

#Monday Musings: Vanya Eftimova Bellinger

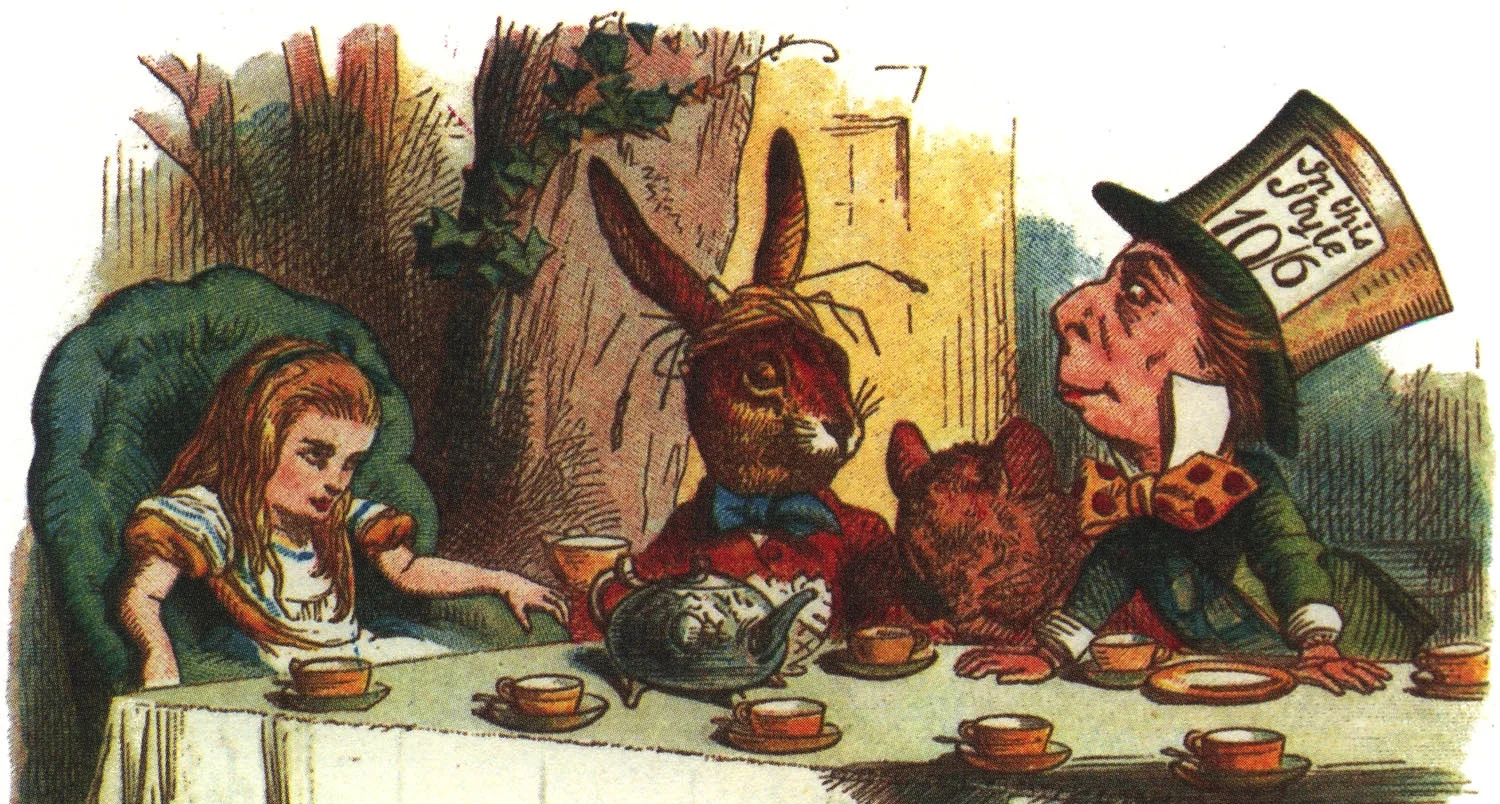

Down the Rabbit Hole: Alice and the Experience of Clausewitzian Genius

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland can help us better understand the experience of Clausewitzian genius. Now, this sounds about as illogical as Lewis Carroll’s famous riddle, uttered by the Mad Hatter: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” But unlike the riddle, which was initially constructed without an answer, the concept of genius links Clausewitz and Alice without artifice. While Clausewitz’s “field of genius...raises itself above rules,” Wonderland is a fantastical space that enables Alice to raise herself not only above rules, but also sense. To see how this is so, we can appeal to Alice and her encounters in Wonderland to highlight the complexity found within military genius. But first we must locate genius in the space where theory fails to map onto reality.

Madam General: Interviewing Vanya Eftimova Bellinger

I first got interested in Clausewitz while living in Germany. It was a time of heated debates on whether US should have invaded Iraq. I think I bought my first copy of On War in German around 2005. Then during my graduate work, Clausewitz was again a big part of the discussions and I started reading it once again. This time, however, I was also interested in Clausewitz, the man and soldier, and so I stumbled upon the whole story about Marie editing On War. None had written anything in depth on the subject and I thought this might be something I could study.

Renken on Carl von Clausewitz's Subjective, Objective, and Trinity

Clausewitz’s great contribution was to “build a snowmobile.” He took the philosophical epistemology of his era, which gave him a means of refining “truth.” He then directed that system to a study of war and availed himself of a Newtonian system to look at cause, effect and engagement. He further located war as a nexus between multiple independent but fused factions. I hope that this is a useful addition to your conception of CvC’s subjective, objective, and trinity.