Over on twitter, Nathan Finney, aka The Barefoot Strategist, posed this question:

An interesting one. How would you go about doing so?

For the purposes of this little exercise, let’s posit that this is over and above an activated and federalized Guard and Reserve component. Wikipedia tells us there’s just over half a million active duty Soldiers right now, with another slightly more than half a million Guard and Reserve troops, yielding a total force of about 1.1 million. Given that the US Army fielded roughly 8 million soldiers in World War II with only half the national population, finding another million or two warm bodies would seem to be rather easy.

But would it be?

Many who went on to perform distinguished service in World War II would today be laughed out of the recruiter’s office.

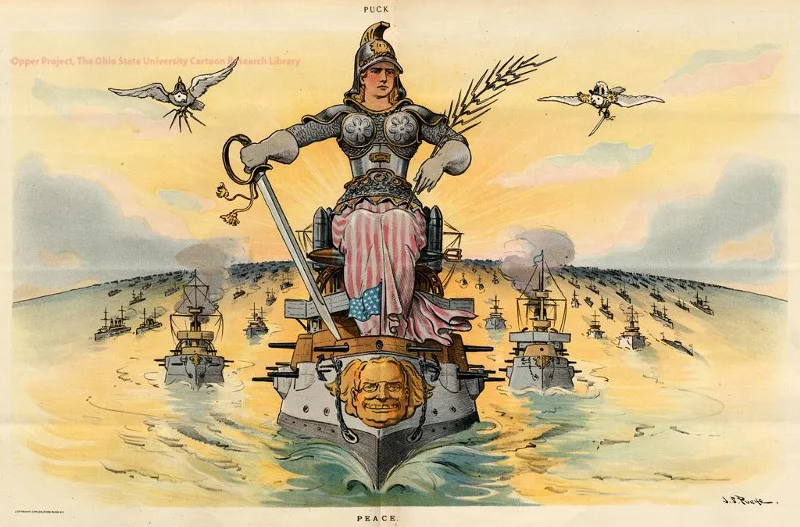

The current military aged male population (for my purposes here I’ve rather arbitrarily selected 18–30 years) is very roughly around 30 million. Approximately 75% of that population is disqualified under current enlistment standards, either due to weight or other health issues, criminal history, or lack of education. That gives us a current population of qualified males of about 7.5 million to recruit from. Given the struggle to recruit 80,000–100,000 of this population annually, I do not think it realistic to achieve the additional numbers purely through voluntary recruitment. That leaves either conscription, or a gross lowering of the standards for enlistment. It should be noted that the standards for selective service in World War II, particularly in the last 18 months of the war, were far, far lower than today’s standards for enlistment. Many who went on to perform distinguished service in World War II would today be laughed out of the recruiter’s office.

There exists today virtually no real political support for conscription. Of course, there is no political support for such a massive expansion of the Army, either, so for the purposes of our exercise, I posit that the political support for enlarging the Army can also be seen as supporting a draft.

Another obvious pool of manpower reserves is the Individual Ready Reserves- those service members who have completed their initial obligation for active duty, or regular drills with a reserve component, but have not yet been completely discharged form the service. Every initial enlistment in the Army is for a term of eight years, with the first three or four typically served on active duty, and the remaining four or five in the IRR. Persons in the IRR don’t perform military duties, nor do they receive pay and allowances, but they are by law subject to recall.

While some IRR troops were subjected to recall for Desert Storm, and a handful for Operation Iraqi Freedom, the last major recall of IRR troops was in the early stages of the 1950–1953 Korean War. I’ve mentioned that the Army recruits roughly 80,000–100,000 people a year. That means roughly the same number leave it annually. The greatest number of these are soldiers whose initial obligation is complete, and decline to reenlist. Of this cohort, some will not be suitable for recall. So let’s just go with a working WAG* of 50,000 over the last 5 years available for recall. That gives us a bump of a quarter million, easing the needed numbers via draft or recruiting. Theoretically, these troops have already been trained, but in reality, even after a very short break in service, the training required to again make them effective soldiers is little different than that needed to train a new recruit.

…the existing Army training pipeline would likely prove incapable of surging production throughput to anywhere near the numbers needed.

Speaking of training the troops, the existing Army training pipeline would likely prove incapable of surging production throughput to anywhere near the numbers needed. The initial training of Army troops is generally grouped by functional areas. Infantry and Armor go through training at Ft. Benning, Artillery at Ft. Sill, and support and service support soldiers go to basic training at Ft. Jackson or Ft. Leonard Wood, and then on to their specialized training at the branch school responsible for their career field, such as the Transportation Corps school at Ft. Eustis, Virginia. Further, one of the advantages of having high quality recruits with fairly long terms of enlistment (which means a fairly long term of training results in a decent return on investment) is that you need fewer military occupational specialties. You can spend the time and money to train a fire control repair technician to fix the electronics on both an Abrams, and a Bradley. But if you desperately need to raise an Army quickly, you are almost forced to limit the breadth of any one job’s training. You’d likely have to split that fire control technician into two specialties, one for Abrams, and one for Bradleys. That means the tooth to tail ratio of our expanded army will suffer somewhat. Still, speed is of the essence, and the old rule of fast/good/cheap applies. Pick any two. In this case, it would be fast/good.

Still, the institutional schoolhouses of the Army simply cannot absorb that large an influx of new soldiers. Some skills simply must be taught at the schoolhouse (say, much of the aviation maintenance field) but a greater portion could be taught in other ways.

In World War II, much of the occupational skill training for soldiers was done in units mobilized for the war. And here our current Army has an advantage over our forebears of 1940–1943. The Army of 1940 faced an expansion of eventually some 2400%. There simply wasn’t a large enough trained cadre of people. Finney’s proposed expansion, however, is significantly more modest. The obvious way to leverage the existing troop formations is to use them as the cadre, the nucleus of new units. For instance, each current Brigade Combat Team might be tasked to form an entire division, with each subordinate battalion transforming itself into a BCT (or rather, forming an additional two battalions to flesh out other BCTs activated). Essentially, everybody gets bumped a paygrade. This would likely result in some decline in the quality of leadership capability, but that would be almost inevitable in any expansion on the scale proposed.

Another challenge for our notional expansion is simply equipping the force. As a practical matter, some things cannot be expanded in such a short time. Two years is simply not long enough to ramp up production of things like helicopters, let alone train the aircrew for them. Other major weapon systems would also face shortages. The Army has a goodly number of M1 Abrams and M2/M3 Bradleys in reserve, but not as many as might be needed. Trucks of all types would be in critical supply. That could be augmented with some civilian procurement for many roles, but the authorized equipment for many units would likely have to be changed.

The minutia of equipage, uniforms, boots, packs, and such, should not be an overwhelming obstacle, but ramping up production and maintaining quality would likely be a challenge. Producing enough rifles might be a challenge, at least in the short term. Equipping the force with modern radios would similarly be a challenge in at least the short term.

Finally, merely finding the space to house and train this notional expanded force would be a great challenge. The US has shed much of the vast amounts of training space it acquired in World War II. Reacquiring it would be next to impossible. For one thing, many of those spaces have become developed. Ironically, even though the proposed expansion is a good deal smaller than the size of the Army in World War II, the battlespace a reasonably equipped force today needs to train is vastly greater. More space is required to effectively train a mechanized battalion today than might be needed for an entire World War II division’s maneuver elements.

…could the US vastly expand from it’s current Army of half a million soldiers to two million soldiers in the space of two years? Probably. But it would yield a force of greatly diminished quality.

So, could the US vastly expand from it’s current active Army of half a million soldiers to one million soldiers in the space of two years? Probably. But it would yield a force of greatly diminished quality.[2] Further, absent an existential, immediate threat to the country, there is simply no political support for such an expansion.

Arthur Barie is a former US Army Infantry NCO and Bradley Commander. This post was originally posted at his blog, “Bring the Heat, Bring the Stupid.” The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Wild Assed Guess

[2] Though quantity has a quality all its own.