The written word is at the heart of The Strategy Bridge. The relationship between reading, writing, and national security takes on special importance in our popular #Reviewing series, a space where we use the written word to focus on how writing illuminates issues in strategy, national defense, and military affairs. The light and shadow from this illumination fall in many ways. What follows here considers that variety and its specific importance to #Reviewing in 2020.

The content of a book under review matters enormously. Sometimes a specific time period is shown in a new way, sometimes a specific institution comes into view, and sometimes it’s a particular personality or personal experience that takes the spotlight. Reviews are full of analysis of a book’s structure and organization, its research methodology, its use of sources and the importance of its argument. We generally try to steer clear of summary for summary’s sake.

All that said, what really makes a review truly exceptional is its handling of a book’s contexts. A book examines a specific context, is written under a variety of scholarly, cultural, historical, and political contexts, and when it arrives on a reader’s desk the look and feel of those contexts may have shifted around. A book written about Jimmy Carter’s relationship to race and the Cold War published in an age of Black Lives Matter takes on new angles in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and the uprisings of the summer of 2020, and the review marks these moments both in its content and in the very fact of the timing of its publication. A novel published in 2020 by an Iraq War veteran torques timeframes as it reimagines the Vietnam War and thus rewrites recent history, and the review of it appeared in the midst of battles over mask-wearing and lockdown orders, when how to keep track of time and live in the moment-to-moment was incredibly difficult. A review of a collection of stories by women from the Revolutionary War through Afghanistan underscores whose voices get heard and whose stories matter are urgent matters.

What’s true for the experience of writing and publishing reviews also holds for reading them. A review is shaped by the contexts in which it is read. In 2020, the contexts have been extraordinary—from the targeted killing of Qassem Soleimani in early January; to the lockdown orders of March and the revolts against them shortly after; to the resurgence, support for, and backlash against Black Lives Matter this summer; to realities around schools reopening online and in person around the country; to the COVID-impacted U.S. presidential race. The individual weight of each of these events was already keenly felt and their collective force was experienced just by living through them.

It’s been a year of Zoom, but books endure. Books endure because we read them in isolation, wrote about them in lockdown, and read reviews about them in quarantine. It will take books—with their focus, length, use of evidence, ability to recreate events, and capacity to make sense of those events after the fact—on 2020 and all it entailed to make the light and shadow fall in ways that illuminate what lived experience alone cannot. And for that kind of long-term, sustained engagement with the contexts in which we read this year’s reviews, we’ll continue to need not just books, but writing about those books.

#TheBridgeReads

Places and Names: On War, Revolution and Returning. Elliot Ackerman. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2019.

Read a review from Katherine Voyles here:

Ackerman can be intensely precise about what he did in war. We’ve already seen that with his gloss of his own citation. By setting his scenes off the battlefield, by both showing the moment-by-moment of war as well as by showing its runup, aftermath and fallout, and by using language to describe experiences that torque speech Ackerman writes of his own distinctive and highly personal war, but in a way that is vividly broad and encompassing.

The Battle of Arnhem: The Deadliest Airborne Operation of World War II. Antony Beevor. London, UK: Penguin Books, 2019.

Read Brandon C. Patrick’s review here:

In The Battle of Arnhem, readers parachute headlong into the operation that took place in and around the Dutch town of Arnhem in September of 1944. Many who study World War II history already have a rough outline of Field Marshall Montgomery’s disastrous operation. Ground and air forces were hastily gathered to capture bridges considered crucial in hastening the war’s conclusion. Bad weather, bad planning, bad radios, and worse luck would pit the undersized allied force at Market Garden against a German enemy that—far from being at its breaking point as previously believed—proved willing to challenge allied efforts for every house, street, and bridgehead.

It’s My Country Too: American Military Women’s Stories from the American Revolution to Afghanistan. Jerri Bell and Tracy Crow (eds). Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2017.

Read Kathryn Sudhoff’s review and interview with the editors here:

As two women veterans who have taken on this project to elevate the voices of other women like them, Bell and Crow are taking an active role in shaping and preserving not only their own legacy but also that of the many undercounted women who have joined them in military service. The pages feel alive with agency and pride. This is a volume with more of a mission statement than a thesis statement. The unmistakable message of this book is: we are here, we have been here, and we have a voice. There are a lot of people who need to hear that.

The World at War, 1914-1945. Jeremy Black. London, UK: Rowan and Littlefield, 2019.

Read Christopher Ankersen’s review here:

As the U.S. enters what may well be later regarded as the Second Interwar Period, where discussion of a return to Great Power Competition has intensified, good histories need to make sense of why such wars come about and how they are fought. Furthermore, as the world wars of the Twentieth Century recede, it may make sense to treat them as episodes of a more massive conflagration, much as we tend to see The Thirty Years’ War as a whole, rather than a start-stop-start string of individual battles. Readers looking for such an offering should look elsewhere, for World at War fails to deliver.

From the Cold War to ISIL: One Marine's Journey. Jason Q. Bohm. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read Douglas G. Luccio’s review here:

Most autobiographies stay within the view of the observer and are limited by their local experience. This book is different in that the author also connects his experience to a grand scale of national level guidance. Similar to corporate strategy and goals, national strategies are articulated through national policy documents. The National Military Strategy is one such policy, which establishes the big picture of the military…Bohm describes thirty years of Middle East policy through two lenses: national policy and his personal experiences. The two perspectives are linked as he describes his role in a bigger picture and several iterations of the U.S. policy.

Killing for the Republic: Citizen-Soldiers and the Roman Way of War. Steele Brand. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019.

Read reviews from Paul Johnstono and Rebecca Burgess here and here:

The book is, for ancient history, fairly accessible, and between that and its celebration of civic virtues and the republican spirit it may garner a significant audience. It does speak to fundamental questions: what made Rome special, and how is Rome relevant today? Republics do need citizens invested in military service and in public life generally. In the military sphere, for example, Eliot Cohen has written frequently and recently about civic virtue and citizen soldiering. While Brand's book asks us to consider the place of civic virtue in modern Republics, its mischaracterizations of Rome's military history and the civic virtues of its citizens make it difficult to recommend.

War Diaries, 1939-1945: Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke. Lord Alan Francis Brooke, Alex Danchev, and Daniel Todman. London: Phoenix Press, 2002.

Read Todd M. Johnson’s review here:

Alanbrooke’s six years at the apex of the British military, at a time when the nation faced its greatest crisis of modern history, tells a story of the inherent value of deep professional competence, a willingness to register dissent, and a commitment to an ideal greater than any single organization or individual. Alanbrooke proved the criticality of remaining unruffled by those things outside of his control, yet demanding the very best from those within his domain.

Winning Westeros: How Game of Thrones Explains Modern Military Conflict. Max Brooks, John Amble, M.L. Cavanaugh, Jaym Gates (Eds). Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2019.

Read a review from Michael Shurkin here:

This is an anthology of 30 short essays written by a diverse collection of mostly American—plus three Australians and an Italian who works in the U.S.—national security professionals. Many are on the faculty at service academies or some of the U.S. military’s various schools of professional military education, quite a few are active duty or reserve officers, and some are civilian analysts and scholars, like me. The contributions cover a wide range of topics, among them general strategy, the tactical use of walls, targeted killings, and human intelligence. Many of the essays are fun, and some are informative. The real value of these essays will probably be to future scholars who want to learn about how national security professionals circa 2019 thought, rather than to people today who either want to get deep into Game of Thrones or learn about modern military conflict.

The Tartar Steppe. Dino Buzzati (1940). translated by Stuart C. Hood. Edinburgh, Scotland: Canongate Books, 2007

Read a review from Christopher Johnson here:

An unseen, unspecified tension lurks throughout the entire book, leaving the reader with a sense of enduring consternation. For aspiring leaders, this novel presents a complex dilemma about human nature and war—or the blessed lack of it. It provides an opportunity to reflect on the challenge of maintaining a mission-focused mindset in an austere environment where all hope seems lost.

“Guide to Tactics, or the Theory of the Combat.” Carl von Clausewitz. trans. Colonel J. J. Graham. On War. New York, NY: Barnes and Noble Inc., 2004.

Read a review from Olivia Garard here:

As Martin Kornberger and Anders Engberg-Pedersen argue, “Strategy is the interface between policy and tactics.” Strategy—the interface—infuses “Guide to Tactics, or the Theory of the Combat” with its purpose and initiative, limited, as we know from On War, by the extent of policy. To understand war requires analysis on both sides of the interface. That means a balanced understanding between On War and “Guide to Tactics, or the Theory of the Combat.” Moreover, for military professionals, “Guide to Tactics, or the Theory of the Combat,” is a better place to start.

Churchill’s Phoney War: A Study in Folly and Frustration. Graham T. Clews. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read Perry Colvin’s review here:

Clews’ book certainly fills a void in the study of Churchill during the Second World War. His analysis does provide a useful study in the difficulty of crafting a strategy that serves multiple constituencies and solves multiple problems. Modern students of strategy should take heart that they are in good company when they seek solutions to no-win scenarios.

U.S. Policy Toward Africa: Eight Decades of Realpolitik. Herman Cohen. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2020.

Read Caleb Slayton’s review here:

Ambassador Herman Cohen is one of many career diplomats, along with ambassadors like John Campbell and David Shinn, who devote personal time to researching, understanding, and commenting on African affairs. Cohen’s most recent work traces U.S. foreign policy in Africa from Franklin Roosevelt to Donald Trump, intertwining historical files and personal insights to weave a picture of what the author titles, Eight Decades of Realpolitik.

Incoming: Sex, Drugs, and Copenhagen. Jennifer Corley, Justin Hudnall, Francisco Martínezcuello, and Tenley Lozano (Eds). San Diego, CA: So Say We All Press, 2019.

Read Meghan Fitzpatrick’s review here:

The book is part of a long American tradition of military memoirs and war literature that extends as far back as the War of Independence and can be traced through the nineteenth century to the Civil War…All human beings are storytellers, and as writers we seek to leave behind a piece of that story for whomever may wish to pick it up. Sex, Drugs and Copenhagen is an important reminder of the therapeutic and communal power of storytelling and its continued centrality to understanding the modern war experience.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf at 75. Thomas J. Cutler (Ed). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read John T. Kuehn’s review here:

This diverse collection is highly recommended, and not just for naval history buffs, but also citizens of all stripes. Leyte Gulf was, and is, something of a milestone in human history. There has not been a major naval battle like it, or even approaching it, since. For 75 years the slaughter on the seas that was common prior to it has been largely absent. The Falklands War of 1982 is the only real exception, and the maritime component was not really two fleets opposing each other, but air power versus sea power. One can only hope that perhaps we might get to 100 years since this pivotal battle, and see the release of a similar anthology without any more bloody fleet actions. If that becomes the case, then Leyte Gulf’s significance will only increase.

Spying for Wellington: British Military Intelligence in the Peninsular War. Huw J. Davies. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018.

Read a review from Frederick Black here:

This detailed study of the intelligence function will prove especially useful to those studying the conduct of intelligence operations throughout the era, whether on the Iberian Peninsula or elsewhere. Davies has also added to the body of knowledge about the Duke of Wellington himself. We get a better appreciation for how Wellington balanced the collected intelligence with his own senses to reach the decisions that propelled him to defeat the French forces in Iberia, and then again with Prussian assistance at Waterloo. Overall, Huw Davies has made an important contribution to the historiography of the Napoleonic field.

In the Trenches: A Russian Woman Soldier’s Story of World War I. Tatiana L. Dubinskaya. Lawrence M. Kaplan, ed. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2020.

Read David Retherford’s review here:

Dubinskaya wrote a book based on her wartime experience during World War I from a unique point of view. Being a woman volunteer soldier, she has left future generations a story from a corner of World War I that English-speaking readers don’t always get to experience.

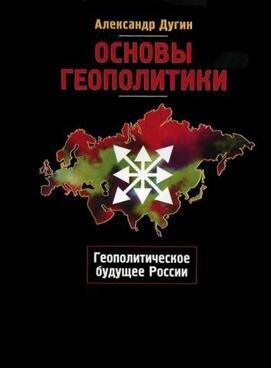

The Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia. Aleksandr Dugin. 1997. Reprint, Moscow: T8 Publishing: 2019.

Read a review from Chace A. Nelson here:

A single book, written in 1997, signalled every significant foreign policy move of the Russian Federation over the following two decades. The United States, Europe, and every nation intertwined with Russia failed to see the signs. From the annexation of Crimea to Britain’s exit from the European Union, the grand strategy laid out in Aleksandr Dugin’s Foundation of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia has unfolded beautifully in a disastrous manner for the western rules-based international order. Perhaps, his words also telegraph the belligerent Putin’s future intentions.

“Vincere!” The Italian Royal Army’s Counterinsurgency Operations in Africa, 1922-1940. Federica Saini Fasanotti. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020.

Read a review from Caitlin Collis here:

For readers unfamiliar with the history of Italian colonialism in Africa, this book provides a detailed examination of Italian counterinsurgency strategy but an incomplete picture of the consequences of that strategy for the local populations in Libya and the Horn.

Empire City. Matt Gallagher. New York, NY: Atria Books, 2020.

Read Peter Lucier’s review here:

This novel is a powerful addition to the American canon. A stunning, short-paragraphed powerhouse that is both eminently readable as a thriller but can also bear the weight of a deep, close reading of the symbolism, rich with interpretative possibility and bold style choices. Yes, what Gallagher is talking about still does matter.

Shatter the Nations: ISIS and the War for the Caliphate. Mike Giglio. New York: Public Affairs, 2019.

Read a review from Sean Barrett here:

Giglio laments that Americans, who still claim to be at war, have made little effort to understand the Islamic State beyond their high-profile attacks. Part memoir, part commentary, and part war story, Shatter the Nations is an accessible, engaging primer on the Islamic State and the challenges facing the region that hopefully serves as an antidote to the war weariness and lack of interest Giglio observes in the American public.

Deglobalization and International Security. Thomas X. Hammes. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2019.

Read Sarah Tenney’s review here:

Hammes provides a current long-look ahead with respect to the unfolding fourth industrial revolution and the dramatic and ubiquitous changes it will bring. Published as part of the Cambria Rapid Communications in Conflict and Security series, this work clearly meets the editor’s goal of “providing policy makers, practitioners, analysts, and academics with in-depth analysis of fast-moving topics that require urgent yet informed debate.” Moreover, Hammes brings together the fields of international political economy and security studies in a way that makes important contributions to both areas.

Touching the Dragon: And Other Techniques for Surviving Life’s Wars. James Hatch and Christian D’Andrea. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2019.

Read Michael Doidge’s review here:

There is an inviting quality to plain-spoken wisdom. We see it these days in succinct and quippy memes and social media posts that distill for us complex personal, national, and global challenges in 280 characters or less. Yet, as satisfying as it may be to blindly accept uncomplicated truths, one of the great dangers in having our biases confirmed is that we stop asking questions of a complicated world, which is how we actually learn, grow, and come to meaningful solutions to problems both simple and complex.

Gettysburg’s Peach Orchard: Longstreet, Sickles, and the Bloody Fight for the “Commanding Ground” Along the Emmitsburg Road. James A. Hessler and Britt C. Isenberg. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2019.

Read Mark Perry’s review here:

For generations of military historians, the Emmitsburg Road, the highway that runs from Emmitsburg in Maryland into southern Pennsylvania—and that, over the course of a single mile, bisects the Gettysburg battlefield—has served as a kind of festering gash in America’s historiographic landscape. The road’s importance is at the heart of Lee’s attack plan on the battle’s second day, when he directed Longstreet to use it as the geographic centerpiece of his assault. Longstreet, Lee said, was to attack “up the Emmitsburg Road.” The problem is that while Lee had an apparently clear vision of what he meant, at least some of his subordinates, and generations of historians, did not.

Women at War: Subhas Chandra Bose and the Rani of Jhansi Regiment. Vera Hildebrand. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018.

Read David Dixon’s review here:

Vera Hildebrand’s work provides an excellent insight into a fascinating piece of World War II history—the creation of the all-female Rani of Jhansi Regiment in Subhas Chandra Bose’s Axis-aligned Indian National Army. Hildebrand covers not only the women of the regiment itself, but also places the regiment in the context of the struggle for Indian independence and the social changes that accompanied it. Whether readers are familiar with the history and personalities already or have never read about them before, Hildebrand’s work has something to offer.

A Brief Guide to Maritime Strategy. James R. Holmes. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read a review by Scott Mobley here:

For today’s naval professionals and scholars aspiring to follow Sim’s advice on strategic studies, A Brief Guide to Maritime Strategy offers an ideal starting point. Concise and well-researched, this highly readable volume will no doubt persuade many readers, most especially young naval professionals, to dig more deeply into studies of history and strategy.

Jet Girl: My Life in War, Peace, and the Cockpit of the Navy’s Most Lethal Aircraft, the F/A-18 Super Hornet. Caroline Johnson with Hof Williams. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Read Tanya Roth’s review here:

While Jet Girl illuminates the ways in which that fraternity still works to exclude women in uniform, it does so on an individual rather than collective level. The reason why Johnson’s shift in focus to the problems servicewomen face is jarring is because for so much of the book, it’s not evident that she faced many problems as a result of being a woman. Jet Girl succeeds most when Johnson shares her experiences honestly, and when she rightly celebrates her accomplishments in naval aviation.

The Russian Understanding of War: Blurring the Lines Between War and Peace. Oscar Jonsson. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press, 2019.

Read B.A. Friedman’s review here:

Jonsson’s thesis is that the Russian government and armed forces believe there has been a change in the nature of war with the advent of the information revolution. Specifically, information warfare is now so potent that it can achieve political goals commensurate with war without recourse to military means. The resulting book offers an efficient overview of trends in Russian military thought since the collapse of the Soviet Union paired with detailed examinations of the two major subjects that have defined those trends: information warfare and color revolutions.

To Kill Nations: American Strategy in the Air-Atomic Age and the Rise of Mutually Assured Destruction. Edward Kaplan. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Read Heather Venable’s review here:

There are so many themes, plots, and subplots within this text that it is difficult to distill the work, but the main argument is that the U.S. Air Force incrementally developed an atomic air strategy from 1945 until the strategy fell apart after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kaplan’s narrative relies heavily on this event to sever the interconnected pieces of atomic strategy and air strategy once the popular imagination began to view atomic weapons as unusable.

The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War. Fred Kaplan. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2020.

Read Paige Cone’s review here:

Kaplan does a wonderful job of historically tracing many of the interactions and viewpoints of presidents and key military officers, but he does not make a serious attempt to theorize how certain sets of interactions, personalities, and/or experiences will conditionally affect nuclear deterrence. Still, The Bomb is both timely and classic, a joy to read, and rich in information for students of military history, American political bargaining, and nuclear strategy.

The Dragons and the Snakes: How the Rest Learned to Fight the West. David Kilcullen. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Read Will Selber’s review here:

Kilcullen’s book is of value, especially for readers who are new to today’s complex battlefield. His use of Snakes and Dragons as a heuristic model is pithy, and his exploration of the evolution of insurgent and terrorist groups is fascinating. David Kilcullen is an erudite, multi-disciplinary scholar with astute observations. Nevertheless, Dragons and Snakes is not on the same level as his earlier books.

The Backwash of War: An Extraordinary American Nurse in World War I. Ellen LaMotte. Edited by Cynthia Wachtell. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2019.

Read Johannes Allert’s review here:

Whether its yesterday’s chemical warfare and shell shock, or today’s improvised explosive devices and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, La Motte’s provocative no-nonsense style and clinical approach to medicine combined with her open critique of the military hierarchy’s approach to waging war, lack of forethought in treating casualties, and overall reaction to global conflict and injustices remains pertinent. Then as now, writing provided a necessary form of release by those who endured the conflict. Moreover, those responsible for waging war are encouraged to read La Motte’s work that illuminates war’s consequences and highlights the importance of sound planning in the treatment of the injured and sick. Though long since passed, La Motte challenges us to question overall war aims and methods employed by those in authority.

The Culture of Military Organizations. Peter R. Mansoor and Williamson Murray (Eds). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Read a review from Frank Hoffman here:

There are many elements that make up a fighting force’s effectiveness in battle; leadership, doctrine, and equipment are most often cited as key determinants. But, as this extensive study shows, organizational culture is also an important factor. Overall, The Culture of Military Organizations convincingly shows that internal culture has an enormous influence on fighting organizations. This influence includes their approach to warfare and their performance in battle.

Colin Powell: Imperfect Patriot. Jeffrey J. Matthews. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2019.

Read a review from Ryan W. Pallas here:

This is a work that succeeds at examining the broad impacts, both good and bad, of a career public servant with an emphasis more on the latter than the former. The author sheds light and places blame on the central figure, although it can be assumed that blame does not solely rest with Powell alone and also resides with others outside the scope of this work. Matthews provides a warning to all that even those most admired are not infallible. This work should be read by all national security professionals, uniformed service members, or any other governmental agency including the department of state and the intelligence community.

An Incipient Mutiny: The Story of the U.S. Army Signal Corps Pilot Revolt. Dwight R. Messimer. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2020.

Read John Abbatiello’s review here:

All of the author’s evidence and contextual explanations surrounding the Goodier court martial make this case clearly and effectively. Messimer’s work also sheds light on why flying training and flight duty pay are so thoroughly regulated in the military today. And over one hundred years later, it reminds us how military organizations in our country must be accountable for their responsibilities to the public, to the Press, and to Congress.

Jimmy Carter in Africa: Race and the Cold War. Nancy Mitchell. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Read a review from Sam Wilkins here:

America can still be a voice against oppression overseas even as it struggles to become a more perfect union at home. For people striving for freedom and justice abroad—from Zimbabwe to Hong Kong to Belarus—the broad movement for racial equality in America illustrates the aspirational and redemptive qualities that make America’s democracy so exceptional. One hopes that this struggle against structural racism, like the first Civil Rights Movement, will strengthen and inform the future of American statecraft.

Progressives in Navy Blue: Maritime Strategy, American Empire, and the Transformation of U.S. Naval Identity, 1873-1898. Scott Mobley. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018.

Read a review from Lori Lyn Bogle, Jacob Kinnear, and Lucas Almas here:

The following interview is a collaboration between Dr. Lori Lyn Bogle and two of her students, Midshipman Lucas Almas and Midshipman Jacob Kinnear, and historian Scott Mobley from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Dr. Mobley’s recent groundbreaking book, Progressives in Navy Blue: Maritime Strategy, American Empire, and the Transformation of U.S. Naval Identity, 1873-1898 is of special interest to current midshipmen at the United States Naval Academy and illuminates the complicated cultural shift in the officer corps as the service transformed from sail to steam following the Civil War that persists to this day.

From Kites to Cold War: The Evolution of Manned Airborne Reconnaissance. Tyler Morton. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read Gregory Moore’s review here:

With meticulous source citations and an impressive bibliography, Morton has produced a succinct, yet informative examination of the evolution of manned aerial reconnaissance from its earliest beginnings to the conclusion of the Vietnam War. In his introduction, the author expresses his intention to not only offer an historical analysis of manned aerial reconnaissance but to fill a “considerable historiographical gap.” In this, he may well have succeeded. Besides serving as a source in itself, the book’s twenty-four-page bibliography will provide current and future scholars of this subject an excellent resource with which to guide their own research and suggest potential topics that can continue to fill the gap he refers to. At the same time, laymen and professionals, not only in the military but in the intelligence community and other areas, will find much to consider as they absorb the narrative and the author’s conclusions.

Subordinating Intelligence: The DOD/CIA Post-Cold War Relationship. David Oakley. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2019.

Read a review from Glenn Hastedt here:

Oakley presents a detailed critical assessment of an understudied area of intelligence policy. It is a deep dive into the politics of intelligence reorganization that assumes knowledge of the subject and not one for beginners. Reaching a full judgement of the merits of Oakley’s argument requires delving into topics which provide the political context within which the subordination of intelligence took place but which he does not provide a framing conceptual contest. Among these are the broader debate on the purposes of American foreign policy: the key threats it confronts and the strategies used to meet them; the constantly changing dynamics of the trilateral relationship of Congress, the President, and the intelligence community; and bureaucratic politics. Looking to the future one could add to this list the increased level of political activism being exhibited of intelligence officers following the 2016 presidential election and the growth of populism in the United States.

Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Just War. Cian O’Driscoll. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Read Jeffrey W. Meiser’s review here:

Cian O’Driscoll has written a thoughtful, erudite book that manages to insightfully explore both just war theory and the nature of war. Across seven pithy chapters plus an introduction and conclusion, O’Driscoll develops an extended argument about why the concept of victory in war is problematic for just war theory and how the integration of victory into just war theory can lead to a more realistic, though tragic, appraisal of just war theory. His conclusions should interest not only just war scholars, but also the broader community of war studies scholars and military practitioners.

The Senkaku Paradox: Risking Great Power War Over Small Stakes. Michael E. O’Hanlon. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2019.

Read Andrew Forney’s review here:

If the U.S. should concede ground on partner territories or interests—as O’Hanlon maintains with his long-term view of asymmetric advantages and sanctions regimes—the nation must articulate a new policy. The other option would be to compete against near-peer competitors in such a manner that maintains the present security environment with enough flexibility to deter conflict and, if needed, limit escalation. Either way, we must move forward into the reality of great power competition with our eyes wide open and with a determined gait, not dozing and stumbling forward.

Hunting the Caliphate: America’s War on ISIS and the Dawn of the Strike Cell. Dana J.H. Pittard and Wes J. Bryant. New York, NY: Post Hill Press, 2019.

Read Heather Venable’s review here:

It is only at the end, perhaps, that the two authors diverge on the true lessons of the fight against ISIS, to include the tenuous gains resulting from the application of overwhelming military force. The mantra to “Kill ISIS” perhaps comes at a cost at all levels of war—strategically, operationally, and tactically. Read critically, Pittard and Bryant’s first-hand accounts provide a starting point for wrestling with the true costs of war on humanity and the limits of hunting.

Docu-Fictions of War: U.S. Interventionism in Film and Literature. Tatiana Prorokova. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

Read Dori Brandes’s review here:

Docu-Fictions of War is a unique investigation into popular culture’s depictions of war, and how civilian narratives interact with military storylines. A reader might be left wanting more artistic explorations, but its contributions to strategic studies are plentiful. That said, with hundreds of sources and a dense epistemological basis, it is not for the faint of heart. The analysis provided by Dr. Prorokova is thought-provoking, even if one is not inclined to accept certain epistemologies, and asserts a robust argument for America’s humanitarian rationale. Docu-Fictions of War is a seminal piece on war narratives that deserves every policymaker’s attention.

Shields of the Republic: The Triumph and Peril of America’s Alliances. Mira Rapp-Hooper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020.

Read Brett Swaney’s review here:

The generation living in the aftermath of World War II understood the value of these structures intrinsically. The most effective and efficient way to protect the American homeland and the economy was through global engagement and forward defense. Today, the barriers between nations and empowered subnational actors continue to shrink in the midst of a peacetime international system that is increasingly dominated by competition and coercion between great powers.

Enduring Alliance: A History of NATO and the Postwar Global Order. Timothy Andrews Sayle. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Read Shay Khatiri’s review here:

Sayle explains how most of NATO’s contemporary challenges are reminiscent of the Cold War. Americans always wanted allies to contribute more, and allies always refused. Competing national interests, an aggressive Russia, and tension between personalities are not new stories. During the Cold War, NATO’s survival was indeed due to the Soviet threat in great measure, but it was also due to the statesmanship of its leaders, including successive U.S. presidents who managed to overcome their disagreements with other NATO allies. Above all, what brought the allies together—liberal democratic values—is itself a threat to NATO due to the election of NATO-skeptic leaders, which the alliance’s leaders had feared in the past.

War and the Art of Governance. Nadia Schadlow. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2017.

Read a review by Joe Buccino here:

Ultimately, War and the Art of Governance is a useful primer on America’s long history of creating civic order during and after combat operations. Despite its flaws, the book offers some wisdom on achieving strategic victory in war beyond success in battle.

All For You. Jessica Scott. New York, NY: Hatchette Book Group, 2019.

Read a review from Katherine Voyles here:

The book satisfies the narrative requirements the Smithton readers demand from romance: it provides escape and a happy ending. But that assessment does not capture the full complexity of a novel that has its characters argue over how to provide for and take care of service members, how to prepare for deployment, and how to deal with its aftermath. And it doesn’t capture the full complexity of a novel that does all of that while pointing to dynamics of race, rank, and gender. It’s not so much that Scott handles these issues in novel or innovative ways in and of themselves, but that she is so deliberate about including them in a genre dedicated to escapism.

On Obedience: Contrasting Philosophies for the Military Citizenry and Community. Pauline Shanks Kaurin. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020.

Read Jim Golby’s review here:

On Obedience is a triumph. It deserves an enduring spot on the reading lists of senior military leaders and on the syllabi of professional military education institutions around the world. Even so, it is an incomplete—and sometimes flawed—triumph, especially as the argument reaches its apex in describing the obedience as negotiation model in the book’s eighth chapter. Shanks Kaurin too easily concedes that those responsible for giving orders also possess the preponderance of power in these negotiations.

The Infinite Game. Simon Sinek. London, UK: Penguin Random House, 2019.

Read Jason Trew’s review here:

Perhaps it is unfair to compare a book meant for popular audiences with a philosophical treatise by a Professor Emeritus of history and literature of religion. Perhaps Sinek and Carse simply had widely divergent purposes despite using identical words. In fact, wrapping this in Carse’s language seems to overburden The Infinite Game. Admittedly, neither Sinek’s recommendations, nor his examples, are necessarily flawed. His central points about the importance of long-term thinking, organizational agility, and transformational leadership, however, are better represented elsewhere.

Innovating in a Secret World: The Future of National Security and Global Leadership. Tina Srivastava. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2019.

Read Kurt Degerlund’s review here:

In Innovating in a Secret World: The Future of National Security and Global Leadership, Dr. Tina Srivastava examines America’s legal and administrative framework for defense technology innovation and asks if it can take advantage of the open innovation model, and especially if it could be used by the U.S. government to manage delivery of innovative technologies in a system that prizes secrecy and delivery of low-cost hardware. This narrow focus plays to the author’s experience working in academia, overseeing a technology development program for Raytheon, and founding a small, innovative startup. Her experience shines in all seven chapters of this short book.

Why America Loses Wars: Limited War and U.S. Strategy from the Korean War to the Present. Donald Stoker. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Read Heather Venable’s review here:

Stoker’s work is essential reading because it forces us to engage with what it really means for a war to be limited. He also pointedly warns the reader that potential opponents understand limited war better than the U.S. does, although he does not definitively prove this claim. But the work is also frustrating. The question of why the U.S. does not win wars is complex. Simply waging wars more decisively is not enough. Stoker quotes Clausewitz to make the point that “there is only one result that counts: final victory.” Of course, Clausewitz also wrote that nothing in war is ever final. And thinking carefully about the limits of one’s political objective and the other essential areas Stoker covers in this work is not enough to change that enduring reality.

Whistleblowers: Honesty in America from Washington to Trump. Allison Stanger. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2019.

Read a review from Ian J. Lynch here:

Whistleblowing has a long and predictably contentious history in America. What distinguishes essential whistleblowing from detrimental leaking? In assessing answers to that question, do the motivations of the individual revealing government secrets matter or should we focus primarily on the benefits and costs of their actions? Driving these tough questions is the considerable tension between the paramount need for secrecy to protect national security interests and the erosion of democratic governance that secrecy can abet.

The Kremlinologist: Llewellyn E. Thompson, America’s Man in Cold War Moscow. Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Read a review from Roger Chapman here:

Though he was a known quantity to all Kremlinologists and highly respected, however, Thompson has largely remained an obscure figure. The online U.S. State Department history of the career foreign service officer Llewellyn Thompson is terse, indicating his service in Austria (1952-1957), the Soviet Union (1957-1962, 1966-1969), and “at large” (1962-1966). Omitted from this thumbnail sketch is Thompson’s service prior to and during World War II. Moreover, the official outline mentions nothing of the Cold War narrative involving the postwar negotiations pertaining to Trieste, the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vietnam, or the negotiations paving the way for the first Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT I). Seldom has a person been so in the thick of important events only to be so largely forgotten.

Demystifying the American Military: Institutions, Evolution, and Challenges since 1789. Paula G. Thornhill. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read a review from Ricardo A. Herrera here:

Paula G. Thornhill has written an easily accessible work explaining the origins and evolution of the United States’ armed forces under the Constitution. She aims to make American military institutions more understandable to readers by discussing their foundations, evolving missions and organizations, how they have functioned in war and peace, and the tradition of civilian control. Thornhill argues that understanding the American military is a central element in understanding the country and its people, an interesting and even useful inversion of the contention that a country’s military institutions reflect their parent society.

Admiral John S. McCain and the Triumph of Naval Air Power. William Trimble. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read a review from Christophe Bellens here:

A serious biography of one of the most important task force commanders in American naval history. Trimble dismantles some of the historical and academic criticism concerning McCain’s scouting during Guadalcanal and his handling of the fleet during typhoons while maintaining fair criticism where needed. McCain comes forward as a real human struggling with the immense challenges posed by handling the navy’s air component combined with managing a huge task force operating in a hostile environment. His offensive thinking, as illustrated during exercises, naval air composition, or his ambitious strikes on Japanese holdings are remarkable. Sadly, the biography rarely compares McCain’s military beliefs with those of his fellow officers.

Aiding and Abetting: U.S. Foreign Assistance and State Violence. Jessica Trisko Darden. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020.

Read Harrison Manlove’s review here:

Understanding how foreign assistance might enable state actors to maintain power in ways that violate the values America espouses in its national policy documents is key to understanding the nature of power in a recipient state. As such, the United States could better tailor such assistance in local contexts that serve the people who need it most while at the same time achieving its strategic objectives. Yet, such a solution is too far out of reach without a workable strategy that connects aid to achieving those broader objectives. This is to say that understanding the reality in which foreign assistance might be used matters only as much as the effort in which the United States is committed to asking the deeper questions, building a comprehensive strategy, and recognizing the limits of its own power in a state far different from its own.

Feeding Victory: Innovative Military Logistics from Lake George to Khe Sanh. Jobie Turner. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, April 2020.

Read Steven L. Foster’s review here:

If a warfighter cannot be supplied, a war cannot be won. Turner’s work is vitally important for operational and strategic planners of every branch of the military, especially those who look for common themes across history that are still relevant today.

How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874–1918. Heather P. Venable. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Read Christopher N. Blaker’s review here:

The year 2025 will mark the 250th birthday of the United States Marine Corps, so a close look at how this service developed its distinctive elite identity offers a fascinating lens through which to view two and a half centuries of American military history. Heather P. Venable’s How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874–1918 does a fantastic job of spotlighting the conception of this unique image during the tumultuous decades that followed the American Civil War and continued through the First World War.

Dogfight over Tokyo: The Final Air Battle of the Pacific and the Last Four Men to Die in World War II. John Wukovits. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 2019.

Read Lewis Bernstein’s review here:

In sum, this latest of Wukovits’ micro historical studies adds little to the debates and knowledge about the final months and weeks of the Pacific War as it concentrates on the operations of a single naval air group operating off the coast of Japan. He builds his narrative using surviving letters, interviews with families and service members, contemporary regional newspaper accounts, radio transcripts, and relevant archival records. The different types of sources Wukovits relied upon caused disconcerting shifts in tone and he was unable to get beyond the flat narrative of the official reports. The most valuable contribution the author makes is detailing the way the U.S. Navy trained its aviators and the way it assembled its naval air groups. The book can only be recommended for those desiring a more human picture of the way these naval aviators were trained and their thoughts and feelings about the war.