Lori Lyn Bogle, Jacob Kinnear, and Lucas Almas

Progressives in Navy Blue: Maritime Strategy, American Empire, and the Transformation of U.S. Naval Identity, 1873-1898. Scott Mobley. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018.

The following interview is a collaboration between Dr. Lori Lyn Bogle and two of her students, Midshipman Lucas Almas and Midshipman Jacob Kinnear, and historian Scott Mobley from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Dr. Mobley’s recent groundbreaking book, Progressives in Navy Blue: Maritime Strategy, American Empire, and the Transformation of U.S. Naval Identity, 1873-1898 is of special interest to current midshipmen at the United States Naval Academy. Mobley, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate and a retired Navy Captain with thirty years of experience as a warrior engineer, illuminates the complicated cultural shift in the officer corps as the service transformed from sail to steam following the Civil War that persists to this day.

How has your experience as a Surface Warfare Officer influenced your research and writing? What initially piqued your interest about this time period, which some refer to as a naval “dark age?”

My experiences as a naval officer largely drove my research for this project. I wanted to understand the origins of the modern naval profession, answering questions like: Why do naval officers today think and act the way they do? What factors explain the Navy’s peculiar service culture? Excellent scholarship by Peter Karsten, Robert Wiebe, Andrew Jewett, Mark Hagerott and others pointed the way.[1] I followed the evidence, pulling the “loose threads” until I landed in the Gilded Age, specifically between 1870s and 1900. As you point out, many people view this period as a naval dark age or historical void.

But the evidence revealed these years to be quite the opposite. If anything they were an “age of enlightenment” for the U.S. Navy. It was a time of incredible energy when technological advances and new conceptions of strategy triggered radical transformations within the naval profession and navy culture. And I discovered a strategic pivot—unnoted by previous scholarship—driven by heated debates that challenged the fundamental assumptions underpinning U.S. national security (much today’s national security debates). This ferment produced a sudden and fundamental shift in the Navy’s primary mission, transforming a backward, antiquated constabulary force into a modern, forward-leaning fleet ready to deter would-be aggressors and defend the U.S. homeland should deterrence fail.

In sum, the period 1870-1900 gave birth to the modern U.S. Navy: technologically, strategically, and culturally. Belying the notion that these years represent a historical void, I found a lot going on within the Navy and a rich trove of source materials.

You claim that the Navy was forced to change traditional officer education when it shifted its mission in the years from 1873-1898 from policing America's maritime empire to that of "national defense." How did this shift impact educating midshipmen at the end of the 19th century?

The shift to a national defense mission didn’t cause an impact on its own. Technological progress was the principal driving force that transformed midshipman education during the nineteenth century.

When Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney reoriented the Navy’s mission to national defense and war fighting in 1886, his decision accelerated the tempo of mechanization within the fleet, and the demand for technologically educated officers to operate that fleet. But the demand signal for mechanically adept officers predated Whitney’s declaration.

Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney in his office. (Library of Congress/Wikimedia)

Indeed, navy leaders established the United States Naval Academy (USNA) in part because they recognized a growing need for officers astute in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) theory and practice. It’s no coincidence that the school opened its doors during the 1840s, at a moment when the Navy began in earnest to shift from sail to steam propulsion, experiment with new types of weapons, and more generally mechanize its warships.

During the mid-1860s, the Academy began to educate cadet-engineers along with midshipmen destined for the line corps. As the Navy began to look towards a mechanized fleet during the 1870s and 1880s, a rigorous technical curriculum took shape at the Naval Academy. By 1876, even line corps candidates devoted more classroom time to mechanical and scientific subjects than to seamanship and gunnery. One 1879 graduate later claimed the Naval Academy became during this period “a school of marine-engineering and kindred sciences that was admittedly not excelled in the United States.”

From 1889 onwards, all students followed the same enhanced technical curriculum until branching into their professional specialties (deck or engineering) for the final year of studies. The shift of naval mission may have helped to spark the decision at this moment, since it helped to precipitate a growing number of modern, mechanized joining the fleet. But the trend towards STEM education at USNA was already well established before the 1880s.

How do you define the “warrior engineer” and how did that class of officer develop after the Civil War?

The “warrior-engineer” identity that emerged within the U.S. Navy officer corps after the Civil War claimed expertise in both naval warfare and harnessing technology. This dual proficiency still defines the professional ethos that most U.S. Navy line officers aspire to today. This ethos values knowledge and ability in STEM fields and, perhaps to a lesser extent, warfighting acumen: strategy, tactics, logistics, etc.

However, before the late nineteenth century, naval officers claimed a different professional identity, that of “mariner-warrior.” The mariner-warriors culture was especially keen on seamanship and navigation skills, but gunnery and infantry tactics (for actions that involved landing sailors and marines ashore or boarding other ships) were also important. I should note that these mariner-warriors were all line or deck officers—that is, ship operators who could someday aspire to ship command.

The U.S. Navy mariner-warriors morphed into warrior-engineers during the period from 1870 to 1900. Technology was advancing in leaps and bounds during those years, revolutionizing communications, transportation, and industrial production. These developments made it possible to build warships and other naval systems that were faster, more maneuverable, more durable, and more lethal than could hardly have been imagined during the earlier age of sail. It also drove the shift in the Navy’s professional culture towards engineering.

During the era of sail power (roughly from the 1770s through the 1880s for the U.S. Navy and its antecedent, the Continental Navy), all officers charged with ship operations were part of the line corps. When the U.S. Navy began to mechanize and adopt steam propulsion during the 1840s, it established a separate officer group, the engineer corps, to operate the new steam plants. The line officers still navigated and maneuvered the ship, and operated the weapons systems. This separation of functions continued until the very end of the nineteenth century. At times it produced bitter rivalry between the line and engineer corps, especially as the latter became more important during and after the Civil War, as the Navy became increasingly mechanized.

During the post-Civil War years, mechanized technology migrated from the steam plant to encompass the entire ship, including “topside” systems and equipment under line officer purview. A “culture of mechanism” (i.e. technology) began to permeate the line corps. As discussed in #2 above, the Naval Academy increasingly stressed STEM education for future engineers and line officers alike. In 1880, one line officer claimed that “Every sea-going officer must...become a practical engineer.” Another officer proclaimed in 1889 that “the line officer’s duties now include a wider range of mechanisms than the engineers.” Ten years later, Congress recognized this new reality by merging all naval engineers into the line corps. This is why line officers run the engineering departments in most U.S. Navy warships today. Other navies, such as that of the United Kingdom, still differentiate between deck and engineer officer career paths and we’ve seen recent calls to resume this practice in the USN as well.

So by 1900, the culture of mechanism and its engineering dimensions were well established with the naval profession. What about the “warrior” aspects? These too gained momentum after the Civil War, catalyzed in part by the experiences of officers who fought in that conflict. In the book I focus a lot on this transformation—from gunners and infantry commanders to strategists and logisticians. It resulted from another culture shift within the navy. As the culture of mechanism emerged within the navy’s line corps, so did a new “culture of strategy.”

A combination of factors shaped the new culture of strategy. Along with Civil War experiences, concerns over growing instability overseas and how new technology was changing how navies would fight vexed naval professionals. They worried that these developments were making the United States both vulnerable and liable to attack. “Career anxiety”also troubled many officers. Historian Peter Karsten coined this concept to describe concerns that too many Americans considered the naval and military professions as marginal to the national interest and not worth funding. In response, some officers felt a need to demonstrate the Navy’s value and educate the public on the importance of national security.

These factors sparked a “Strategical Revolution” within the U.S. Navy during the 1870s and 1880s. Strategy-related ideas, studies, and practices attracted strong interest among some naval professionals. In 1882, the Navy established the Office of Naval Intelligence. Although ONI's primary mission was to gather information on foreign naval technology, it quickly became a center for strategic planning. Then in 1884 Commodore Stephen B. Luce convinced the Navy’s civilian leadership to establish a war college at Newport, Rhode Island, an institution aimed at developing strategy-minded commanders.

The Naval War College quickly became a battleground for a cultural struggle, wherein advocates of mechanism and strategic cultures vied for control of the Navy’s future. Internal conflict arose over institutional arrangements, organizational authority, and how to allocate the Navy’s limited budgetary and personnel resources. Twice between 1888 and 1895, the champions of mechanism nearly shuttered the War College. It's a dramatic story that the book recounts in some detail. However, the Navy’s civilian leadership ultimately came to see value in both strategy and mechanism in building an officer corps for the twentieth century. As a result, the Naval War College survived and both cultures thrived, together forging the dichotomous “warrior-engineer” identity of modern naval officers.

Admiral David D. Porter is often described as a traditionalist who rejected progress and valued sail over steam. Was he transformed into a progressive or was his post Civil War policies determined by the lack of appropriations?

Porter certainly appears to us as a “traditionalist” during the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, but he later championed the metamorphosis from mariner-warrior to warrior-engineer.

As the Navy’s senior flag officer in 1869, Porter directed all commanders to equip their ships with sail rigs, including steamers originally constructed without masts or spars. At the same time, he restricted the use of coal to emergency situations, ordering instead that ships cruise under sail alone. Porter explained these measures as an effort to economize, but the admiral also articulated a vital need to “instruct the young officers of the Navy in the most important duties of their profession.” Porter wanted the line corps to preserve traditional mariner-warrior skills such as seamanship, navigation, gunnery, etc., rather delve into steam engineering and other mechanical disciplines.

The fallout from the Virginius affair in 1873 (which triggered a brief war scare with Spain) shifted Porter’s perspective. The Navy’s poor response to that episode convinced Porter that the aging Civil War-era fleet could not adequately protect the United States, rendering the nation strategically and technologically vulnerable even to lesser naval powers. Thus he began to press strongly for naval modernization, warning that the Navy’s fleet of venerable wooden cruisers and rusty ironclads was “unsuitable for war purposes.” Porter now wanted to create a modern, mechanized fleet. And during the 1880s, he became a leading advocate for the new Naval War College, closely allied with Luce, Mahan, and other progressive leaders.

Which came first in the Navy: Professionalism or Progressivism? Could the two terms be used interchangeably? If not how do you differentiate between the two?

Professionalism and Progressivism are two distinct concepts. As understood today, “Professionalism” describes how well the practitioners within a given occupation embody specialized expertise, a service ethos, and a sense of group identity centered on their vocation. On the other hand, “Progressivism” is an approach to problem-solving that emerged in Western societies towards the end of the nineteenth century. Progressive reformers—both inside the Navy and within broader society—embraced an ideology of science, technology, and expertise. They advocated the use of professionalized specialists, scientific inquiry, teamwork, and continuous innovation as tools for social transformation.

Within the U.S. Navy, professionalization and progressivism rose together. By 1873, the Navy developed a substantial professionalizing infrastructure: educational institutions, ethical and competency standards, certification mechanisms, and professional associations. Some of this infrastructure—the professional associations and educational institutions, in particular—was erected or fine-tuned after the Civil War by officers who embraced the progressive ideology: Steven Luce, Foxhall Parker, Theodorus Mason, and their contemporaries. In turn, the professionalizing infrastructure—the Naval Academy; the Naval War College; the U.S. Naval Institute and its journal, the Proceedings; etc.—helped to energize and focus progressive reform across the service, especially in the fields of mechanism (technology) and strategy (war-fighting).

You claim that other professions did not professionalize as early as the Navy. Why is that?

Cultural factors may help to explain why the Navy and other military branches acquired the hallmarks of a modern profession (as defined by Robert Wiebe) earlier than other occupations. For one, naval officers shared a general unity in perspective and purpose not achievable in wider U.S. society. The unique experiences and camaraderie of sea duty certainly helped to shape a common outlook and sense of identity. In addition, the Navy’s officer corps represented a small and stable cadre (averaging between 1,000-2,000 persons during peacetime) that was homogeneous (almost entirely white, male, and middle class), uniformly educated (USNA after 1845) and hierarchically organized, with a well-defined structure of rank and custom.

The unifying qualities of naval service nurtured conditions that encouraged officers to find common ground and achieve a degree of consensus sufficient to advance important new ideas relating to professionalization (education, forming associations, etc.) with relative timeliness. Government funding also played a role, funding centralized institutions (such as the Naval Academy and Naval War College) to standardize the process of forming and credentialing a cadre of professional experts.

By comparison, most other occupations in the nineteenth-century United States embodied more eclectic and less closely-knit memberships, inconsistently schooled and credentialed to a hodgepodge of professional and educational standards. No wonder it took longer for these groups—doctors, lawyers, educators, etc. to establish themselves as modern professions!

How did naval officers pioneer a change in graduate education?

Stephen Luce deserves the most credit for introducing progressive postgraduate education to the U.S. Navy. The Naval War College was his brainchild. Like other graduate program innovators during the 1870s and 1880s, Luce envisioned the new Naval War College as a seat for both researching and teaching advanced subjects, in this case naval warfare. Thus the pedagogical approaches he “baked into” at the war college mirrored in many respects the methods of nascent programs in history and political science at Johns Hopkins University, Columbia College, and elsewhere. As did its civilian counterparts, the early Naval War College emphasized “scientific” approaches and grounded its principal work in historical studies, comparative method, and a collaborative learning culture.

Historian Robert Wiebe assesses the emergence of progressive graduate schools in the United States during the Gilded Age as an essential building block for professionalization. He describes these new institutions as “outposts of professional self-consciousness, frankly preparing young men for professions that as yet did not exist.” According to Wiebe, each program possessed a distinctive, specialized curriculum; centers for research, discourse, and learning; the ability to inculcate values and goals; and the authority to legitimize practitioners. Luce certainly understood the Naval War College mission in similar terms.

How did the Office of Naval intelligence exemplify progressivism? Why didn't the ONI get the same credit as Luce and Mahan for the Navy's strategic advancements?

ONI’s founding director LT Theodorus Mason replaced the Navy’s traditional ad hoc approach to intelligence work with an efficient, progressive framework. Systemization, specialized expertise, function-based organization, discursive problem-solving (teamwork) and scientific method permeated the new agency. The Secretary of the Navy’s 1882 order (likely drafted by Mason) establishing the office reflected an attempt to recast previously inchoate intelligence functions under the aegis of a central authority. Blending his own vision with the ideas of senior officials, Mason designed internal processes and procedures with efficiency in mind. ONI’s information cataloging system exemplified this approach. Mason’s methods at ONI presaged those at the progressive bureaus of research that would emerge in my U.S. cities the United States after 1900. Just as the municipal research bureaus “provided endless data . . . and the skill for drafting some of the more complex ordinance[s],” ONI collected, synthesized, and published large amounts of information. In time, officers at ONI would also draft complex strategic plans based on such information.

ONI probably receives less recognition than as a pioneering center of strategic synthesis and planning because it didn’t remain in the strategy-making business for long. During the 1890s, strategic planning diffused to several institutions within the Navy: the Naval War College, the Bureau of Navigation, and the fleet commanders, along with ONI. After 1900, the new General Board assumed lead responsibility for strategic planning (see John Kuehn’s excellent book: America's First General Staff), and later the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) took over that function. So it seems to me that these later developments obscured ONI’s early strategic role. Also, neither Luce nor Mahan had much to do with ONI’s establishment and early achievements, so the lasting fame accrued by their accomplishments (the Naval War College, the Influence of Sea Power series, etc.) didn’t encompass ONI.

You argue that the ABCD ships (The Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, and Dolphin) were not the great technological leap the Navy thought they were. Why wasn’t the technology better?

The ABCD ships did mark a historic technological turning point for the U.S. Navy, replacing traditional wood and iron construction with steel and incorporating other modern inventions, such as electricity. However, while the public may have perceived these new warships as a “great technological leap,” I think most Navy professionals recognized that the ABCD ships represented an evolution in U.S. naval technology, rather than a revolution. Several factors encouraged the Navy to take this incremental approach: (1) political compromise in Congress, which limited funding; (2) technical risk (unproven warship designs and a learning curve in U.S. shipyards for constructing steel ships); and (3) expectations during the early 1880s that the Navy would continue its traditional constabulary role.

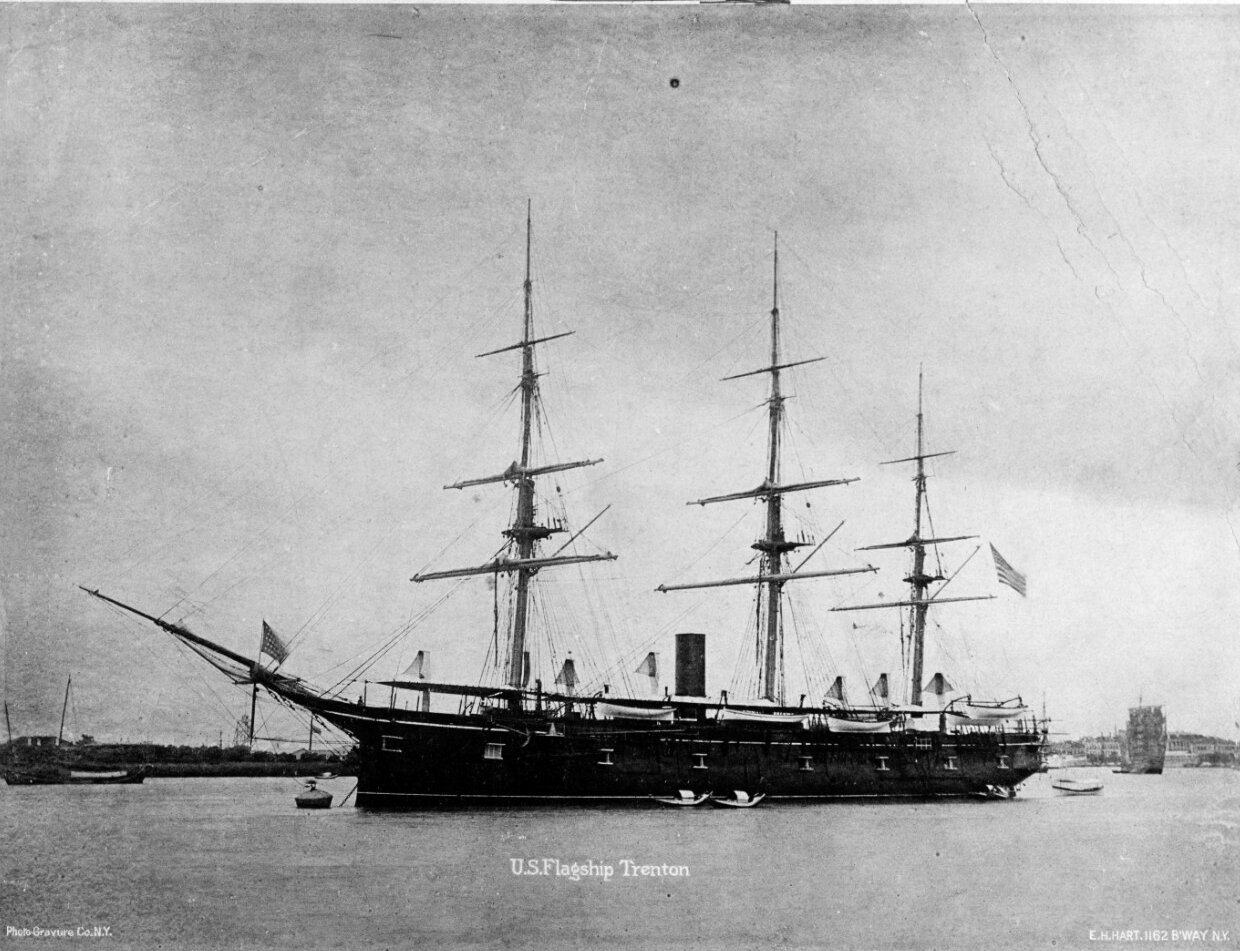

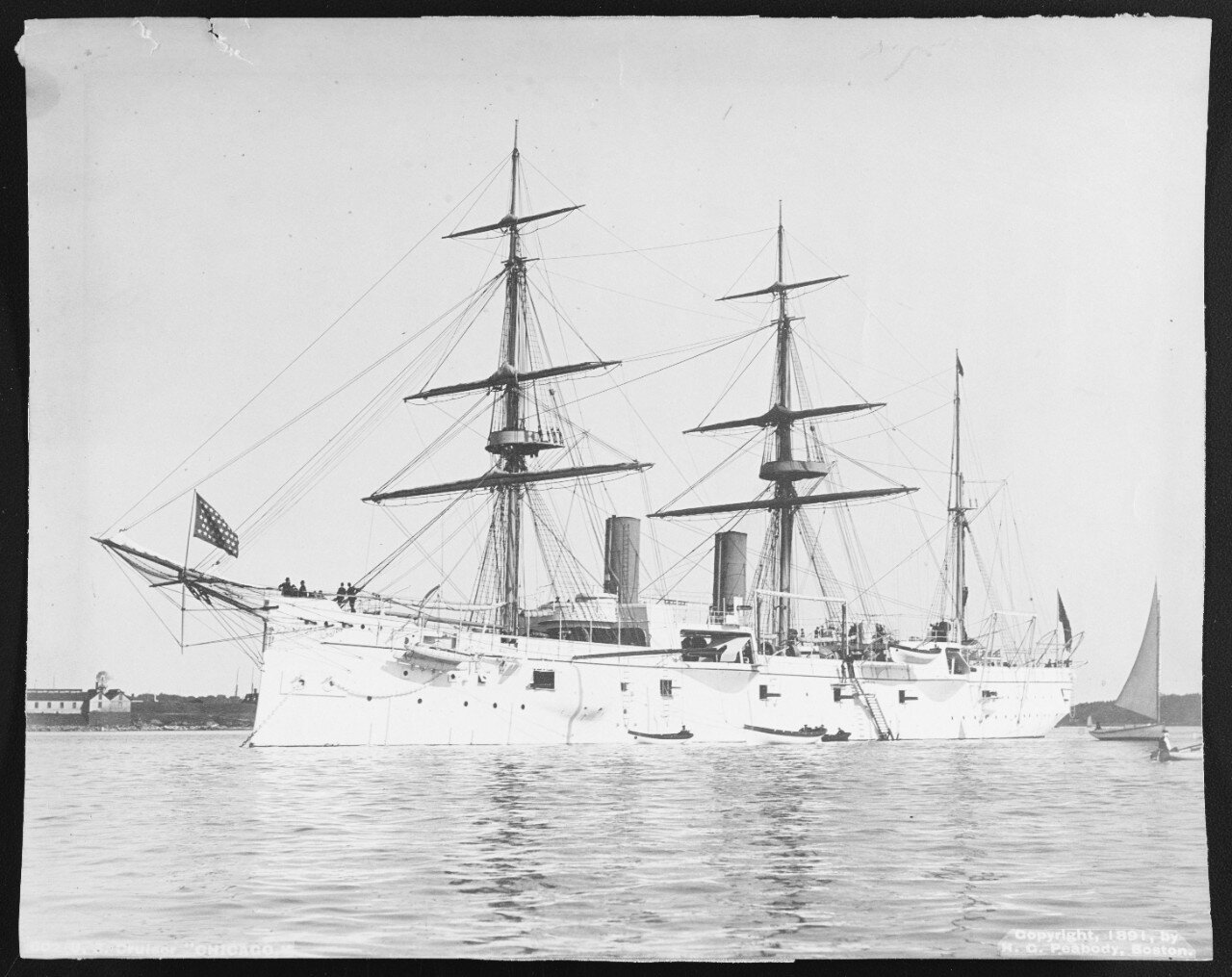

Thus the Navy built these ships to fulfill constabulary and commercial missions. And despite official acclaim for the new steel Navy—backed by widespread public enthusiasm—the new vessels reflected only incremental improvement over older warships such as USS Trenton, a large wooden frigate constructed ten years earlier. Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago (commissioned 1887-1889) all resembled the older ship in general appearance, displacement, speed, and caliber of main battery (see images below). Both cruiser types—wooden and steel—featured a mixed propulsion system of sail and steam that provided for economical transit and operational flexibility on distant stations. This hybrid arrangement could develop top speeds of thirteen or fourteen fifteen knots—adequate for most peacetime constabulary contingencies. Furthermore, like Trenton, the steel cruisers bristled with modern eight-inch rifles, an armament that could command respect from primitive rulers and lesser nations but would hardly match the capability of a great power battle line.

When you compare the ABCD ships to the follow-on generation of new warships constructed for the U.S. Navy, you can see tremendous changes. While the ABCD designs looked backward in many ways, the cruiser USS New York (commissioned in 1893) looked to the future, approaching a modern Ticonderoga-class cruiser in size and basic appearance. New York, which joined the fleet only four years after the final ABCD cruiser (Chicago) entered service, was entirely powered by steam engines, possessing neither no sail masts nor rigs; it was heavily armored and brandished more firepower than the earlier ships.

Why was New York so different from the ABCD ships? Advancing technology and experience building steel warships offer part of the explanation. But more fundamentally, New York was one of the first ships designed for the Navy’s new mission (after 1886, see question #2): to defend the nation by being able to vanquish the fleets of threatening maritime powers, rather than simply carry out constabulary duties overseas.

Junior naval officers appear to have had a greater impact on naval policy in the 1880s and 1890s then they do today. Why?

Several factors help to explain how junior officers (Ensign to Lieutenant Commander) were able to influence naval policy during the Gilded Age. For one, the Navy was a much smaller force back then. The entire active duty officer corps numbered perhaps 2,000 people, compared to about 55,000 today. So the “pond” was much smaller, making it easier for individual voices to be heard and for junior folks to access senior leadership.

A second factor was the slow rate of promotion. Coming out of the Civil War, the Navy’s officer ranks were overpopulated, especially in the middle grades. Congress created this surplus by legislating that “volunteer” officers with exemplary war records be retained on active duty. (These volunteers equate to today’s naval reserve officers.) However well intentioned, this legislation effectively throttled promotion, which was based entirely on seniority. Many officers, especially lieutenants, languished at the same pay grade for perhaps twenty years or more. Today senior O-5s (captain selectees) typically have that much service! Although the nineteenth-century officers were junior in rank, many enjoyed tremendous credibility, earned through decades of capable service. So their opinions and counsel could carry significant weight, despite their rank.

Another consequence of the overpopulated officer ranks was a surplus of “free” time, away from operational assignments. The Navy was liberal about granting officers half-pay leaves of absence so they could pursue studies, work in the private sector, travel abroad, etc. And the operational tempo in the fleet was slower than today. These circumstances gave officers time to read, reflect, and write.

And read, reflect, and write they did! I think these pursuits laid at the heart of junior officer influence during the late nineteenth century—and they still carry the most weight in 2020. But how many junior officers today engage in these activities? When do they have time? Many Gilded Age junior officers published prolifically: books, pamphlets, articles in professional journals and popular magazines, etc. One example from the 1880s is Theodorus B.M. Mason. Mason authored numerous articles and reports during the 1870s, and traveled abroad on leave. With fourteen years of service (typical for a new O-5 today) Lieutenant Mason convinced the secretary of the navy to establish an office of naval intelligence. And dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Mason’s peers engaged in similar endeavors. I sense that we don’t see this proportion of JO engagement today (for a number of reasons).

Is naval “progressivism” still alive in the Navy today?

It is. The progressive method or “ideology” was new-fangled in the 1880s and 1890s but was widely adopted by the Navy, other government institutions, private business, etc. after 1900. It still frames how many people work within the Navy today: developing and leveraging expertise, employing scientific methods (i.e. critical inquiry), discursive problem-solving (i.e. teamwork), and pursuing innovation and continuous improvement.

How did your postdoc at the Naval Academy change your thinking about education at the Naval Academy? Do you think a culture of strategic thinking belongs at the Naval Academy, or is this best relegated to the USNI and Naval War College?

Having experienced the Naval Academy education first-hand as a student (1974-1978) I found it to be excellent preparation for a naval career and more broadly, for life. My subsequent stint teaching at USNA as a post-doctoral fellow reinforced these earlier experiences. It appeared to me that the academics and overall program at the Academy were, if anything, more challenging than during my days as a midshipman.

The Naval Academy curriculum strongly emphasizes STEM subjects—that's been the case since the 1860s and it remains vital today. This emphasis comes as no surprise, given the complexity of today’s naval platforms and systems and, most important, the need for officers who can lead the sailors and marines who operate and maintain this complex technology. That said, the Academy has an equal mission to plant intellectual seeds and interests that will one day sprout into effective strategic commanders. What I mean is that good strategic thinking doesn’t appear overnight; it requires time to “ferment”: learning, reflecting, and practicing over the span of years, ideally starting at a young age.

So midshipmen should study history and become familiar with basic strategic vocabulary and concepts. They need to build a foundation for strategic thinking that the war college and self study can further develop as their careers progress. Along with the required history and government classes, a primer such as A Brief Guide to Maritime Strategy might structure a course (or part of an existing course) by focusing on the fundamentals of strategy.

History majors at the Naval Academy are still required to take engineering courses. Is this enough to create "warrior-engineers"? Should more be done?

I think that a balanced education incorporating strong doses of humanities and STEM is the best approach for developing effective 21st-century naval leaders. Just as during the late 19th century, today's officers must lead the operators and maintainers of complex naval platforms from day one, before rising later in their careers to strategic command. Indeed, the USNA history major offers the ideal mix of humanities, social sciences and STEM needed to forge the types of officers most needed today by the Navy and Marine Corps. Full disclosure: I majored in history at USNA, before going on to a rewarding career as a nuclear-trained surface warfare officer.

A pickier item just for me as I am really into hero studies: Did the recognition of Lt. Bradley Fiske's "fire control" on the Petrel during the Battle of Manila Bay (p. 264) represent a change in heroic conduct or was it an attempt by the Navy to make engineering education more attractive? Wasn't gunnery accuracy under 2% in this battle? Was Dewey recognizing his heroism because he stayed on the deck during the battle rather than his fire control abilities?

Fiske served as navigator in the gunboat USS Petrel, which formed part of Commodore Georger Dewey’s squadron. On the morning of 1 May, 1898, Dewey led his force into Manila Bay to attack the Spanish squadron under Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo. Fiske observed the battle from a perch high aloft in Petrel’s mast, a position that enabled him to employ his new invention, the stadimeter (an optical range-finding device), to guide the fire of the ship’s batteries.

According to Fiske, using the prototype stadimeter at Manila Bay was an arrangement worked out between him and his commanding officer. I found no evidence suggesting that this decision involved higher authority. Regarding accuracy, Fiske’s observations (recounted below) indicate poor shooting on both sides. Fiske also claims credit for a somewhat better performance from Petrel’s gunners. However, my guess is that Fiske received commendation mostly for his heroism at Manila Bay, rather than for his inventiveness.

Excerpt from Fiske’s account of the battle:

I think everybody was disappointed at the great number of shots lost. Our practice was evidently much better than that of the Spaniards, but it did not seem to me that it was at all good. There was no question in my mind that the two principal causes were the uncertainty about the true range, and the fact that each gun captain felt it was incumbent upon him to fire as fast as he could.

I measured the ranges, or distances, by means of the stadimeter, an optical instrument of my invention, first setting the instrument at a certain graduation, which represented the height which I estimated to be the height of the ship we were firing at. The distance which the stadimeter then indicated, I shouted to the captain, who then ordered the gun-sights to be set at that distance. At first our shots fell short. I then set the instrument at a graduation representing a greater height of mast, which caused the instrument to indicate a greater distance, and the shots to go farther. After a few trials I found the correct setting for the stadimeter, and after that the shots grouped around and on the target in a satisfactory way.”[2]

Editor’s Note: For more from Scott Mobley on Progressives in Navy Blue, see The Strategy Bridge Podcast:

Lori Lyn Bogle is a professor at the U.S. Naval Academy where she teaches American Naval History and a number of other courses. She is the author of The Pentagon's Battle for the American Mind: The Early Cold War. Her current book project is on Theodore Roosevelt's use of publicity and modern sociological principles as he rose in politics.

Jacob Kinnear is a Midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy from Norfolk, Virginia. He is a history major hoping to become a Surface Warfare officer.

Lucas Almas is a Midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy from Maryland. He is a history major specializing in the development of naval technology. He hopes to become a Surface Warfare officer.

The views expressed are the authors’ alone and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: USS United States, the first of the original six frigates of the United States Navy, seen here defeating HMS Macedonian in battle, before taking her as a prize during the War of 1812. (Fred Pansing/Wikimedia)

Notes:

[1] Karsten, Peter. The Naval Aristocracy: The Golden Age of Annapolis and the Emergence of Modern American Navalism. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008. Wiebe, Robert H. The Search for Order, 1877–1920. 1st ed. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967. Jewett, Andrew. Science, Democracy, and the American University from the Civil War to the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. Hagerott, Mark R. “Commanding Men and Machines: Admiralship, Technology, and Ideology in the 20th Century U.S. Navy.” PhD Dissertation, University of Maryland, 2008.

[2] Bradley A. Fiske, From Midshipman to Rear-Admiral (New York: The Century Co., 1919), page 249.