Naval Command is clearly aimed at officers who aspire to or are preparing to assume command. However, it can also serve as a valuable resource for junior officers who wish to better understand the lens through which their commanding officers view their own responsibilities. In several instances, Cutler distilled lengthy contributions down to tightly presented summaries of the salient details. This skillful editing yields a 194-page book that is neither intimidating in scope nor size. While Naval Command can be read cover to cover, it may be best used in the traditional “wheel book” sense — a professional reference manual that an officer can return to time and again for insight and guidance.

Taking Writing on to Real Pages

If you follow The Bridge, you've probably read essays such as Williamson Murray’s views on Mission Command, or something more academically focused such as the strategy tome, Makers of Modern Strategy. A tough fundamental question for me to answer, is “How the hell do I still make this interesting?” Audiences are interested in blog posts, they are quick reads, they can spread via email and social media like wildfire. The rare whitepaper or essay that makes the rounds to the force really needs the right stuff.

John Boyd’s Revenge: How ISIS Got Inside Our OODA Loop

One of the most influential names in strategic studies is that of Colin S. Gray. He is not only an authority in the field, but a prolific writer. His book The Strategy Bridge — the one that gives this blog a name — is no less than a theoretical system which organizes the entire field, including the ranking of major theorists into tiers. Gray is no fan of John Boyd, the irascible Air Force Colonel who invented the well-known “OODA loop” but wrote nothing, preferring instead to communicate with his audience through grueling presentations rather than written works. The slides can be confusing, and the only academic treatment is Science, Strategy and War by Frans P.B. Osinga, so it is understandable that Boyd’s ideas haven’t achieved much purchase in academic strategic studies. Gray is emblematic of most authorities even though Boyd has a devoted following amongst practitioners and an annual conference devoted to his ideas. Increasingly it seems like Boyd’s ideas were quickly dismissed by strategic theory and then left behind.

#Reviewing Buzzell

Now comes Thank You for Being Expendable: And Other Experiences, a collection of occasional essays that date back as far as 9/11 — Buzzell was on the ground in New York City to watch the Twin Towers fall — and as recent as a 2015 review of American Sniper. Many chapters date from the years Buzzell bounced around the country researching Lost in America. Once more we see Buzzell enchanted by aspects of American culture untouched by prosperity and respectability.

Anti-Hero Narration of War: #Reviewing “Thank You for Being Expendable”

Colby Buzzell’s anthology of short stories, Thank You For Being Expendable, is the punk rock alternative to Service Academy and/or Ivy League-educated military officer GWOT-memoirs. Buzzell is a hard drinking, chain smoking, enlisted Stryker Combat Brigade infantryman who not only fought in Mosul during one the deadliest years of Operation Iraqi Freedom but also witnessed firsthand the events of 9/11 in New York City.

The Specialist Speaks: #Reviewing “Thank You for Being Expendable”

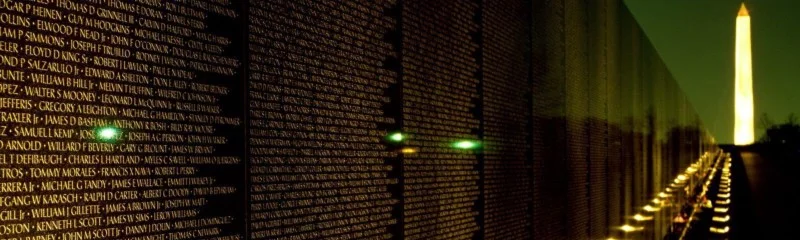

Reflections on Memorial Day — Past and Present

Broadening Remembrance on Memorial Day

As Americans get ready to honor the sacrifices of the nation’s military this Memorial Day, is it time to consider broadening the spirit of this U.S. holiday beyond the ‘Armed Forces’? Originally called Decoration Day, since the Civil War Americans have honored their fallen warriors. Even today when fewer Americans serve in the all-volunteer force, Memorial Day holds a sacred place in the United States. Millions of Americans visit graves and honor the fallen with flags and wreaths. Millions more commemorate their actions in small town ceremonies across America and thousands will even visit overseas cemeteries in Europe, Africa, and Asia. Others attend silent drills, parades or ocean-side fly-bys, fireworks displays or simply spend time with family and friends. All of these commemorations, tombstone decorations and prayerful reflections are ways of remembering America’s brave military men and women who gave their lives so that others might be free.

They Were Better Than That…So Are You

So there I was, a fairly familiar platoon leader, having spent the last eight months training with my platoon from individual skills and Expert Infantry Badge testing through our Mission Readiness Exercise at the National Training Center. It was early-2011, and in a little over a month we would board flights for Afghanistan, headed for a remote outpost in the northern part of Kunar province. We were ready. Our leadership was a cohesive team. The soldiers knew their jobs. I was a bit nervous about how I would perform in combat, but I was confident that my training would see me through successfully.

A Fragile Peace

This weekend will mark the celebration of Memorial Day in the United States. It’s a time to remember veterans who died for their country, but it should also be a time to ask what their service accomplished. War, with all of its horror, must have a compelling purpose, and the only worthwhile intent is to create a better peace. Unfortunately, the peace generations of veterans fought for is fragile, and must be carefully preserved.

The True Meaning of Memorial Day

Most vets appreciate being thanked for their service, but if it happens on Memorial Day, there are many that will tell you to be thankful instead for those that never made it home. Memorial Day, celebrated at the end of May every year, is meant to remember them, our comrades-in-arms, that gave the ultimate sacrifice. After 20 years in uniform, Memorial Day means more to me (and many veterans like me) than it might to other Americans.

Scarcity as a Source of Violent Conflict

Scarcity should both interest and scare strategists and policy makers. It refers to a mismatch between the demand for and availability of a commodity. It helps drive free markets, and informs value. But strategists and policy makers should contemplate it because scarcity, both real and perceived, drives much of human conflict, and it has reared its head again, this time in Yemen.

Army-Air Force Talks

Dan and Dave, no relation to the famous Olympic decathletes, began a dialogue following a workshop on the development of an Air Force Operating Concept. At the conclusion of day 1 of the workshop, Dan and Dave had a discussion on the future of the military; to include the direction our respective services are headed. The idea popped up that these deep discussions should be published, for others to read and debate. The richness and value of discussions on the future of warfare is worthless if left between two people.

We know how to strike, but can we achieve victory?

The U.S. military has been, without a doubt, innovative during the past century of warfare. Advances in technology have allowed the U.S. armed forces to become the most expeditionary, precise, and lethal force in the world. During the Cold War, the bulk of defense spending went towards countering the Soviet threat. In the end, the strategy was a success; the Soviet Union fell without direct confrontation. In the meantime, the U.S. military’s culture adapted to the political and economic realities of the Cold War. Although the Cold War has technically been over for 25 years, elements of that era’s defense culture have proven extremely resistant to change.

The Human Costs of War: Justin Miller’s Story

Bad Intelligence and Hard Power

If you are invested in defending torture on the basis of its potential utility, it would be prudent to frame the issue by claiming that the torture of captured extremists has led to useful intelligence. That way, your detractors will respond either by arguing that torture did not lead to useful actionable intelligence, or that torture is ethically unjustifiable even if it is a useful method of information gathering. Either way, the pro-torture argument comes out ahead — because given this way of framing the issue, the worst-case scenario is that torture is ineffective and unethical. But, in fact, that is not the worst-case scenario. There is a scenario far worse even from the most utilitarian point-of-view — a scenario involving bad intelligence.

In the Information Age Centers of Activity > Centers of Gravity

After the 1991 Gulf War, the character of war changed dramatically, and not in the way America believed it would. While spell-binding CNN footage sold us on the value of precision attack, our adversaries across-the-board learned two very different lessons. First, if it matters, it has to move and hide. Second, reclaiming the initiative from the US is always possible, as Iraqi SCUDS nearly proved. Their new playbook was clear — absorb, re-form, and reengage. Shock and Awe had its moment, but is gone for good. That is, unless we shift away from the idea we can take down a resilient, adaptive system by attacking centers of gravity, and instead harness our ability to observe and affect a system’s centers of activity.

Achilles and Odysseus in Modern Warfare

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to warfare. One is to be strong and powerful. The other is to be smart and cunning. The Greek terms for these concepts are biē and mētis respectively. In The Iliad and The Odyssey, Achilles personifies biē, and Odysseus embodies mētis. The United States military can and should learn a lesson about its operational art from the lives of the two mythological warriors.

Narrative: Everybody is talking about it but we still aren’t sure what it is.

In his 2009 work, The Accidental Guerrilla, David Kilcullen summed up the different communication approaches by Al Qaeda-backed insurgents and the Western-led Coalitions seeking to defeat them. “We use information to explain what we’re doing on the ground. The enemy does the opposite — they decide what message they would send and then design an operation to send that message.” The observation was not new; it had been described in similar fashion among the Strategic Communication and Information Operations community since the commencement of the Global War on Terror and earlier and is often referred to as “narrative-led operations.” Kilcullen did however bring the concept to main-stream military thinking.

This Anzac Day: Defining the Contemporary Veteran

Author's Note: This post flows from thoughts during Anzac Day and from reading James Brown’s book Anzac’s Long Shadow.

Today is Anzac Day, the day of the ‘exceptional digger’[1] and time to reflect on wars past. It is a curious day for those of us with recent operational experience as our part in Anzac Day commemorations is yet to be precisely defined.

Photo by Neil Ruskin, Afghanistan 2008

Contemporary veterans are a diverse group with no ingrained stereotype. Some are still serving military members and will march in today’s Anzac parades with their units. Others have transitioned to civilian life and may march under an ex-services banner. Some will opt to stand undetected on the sidelines while others who hold painful memories of war may wish the day was not filled with military reminders. So how does the stereotype of ‘Anzac’ and ‘veteran’ compare alongside the mould of our most recent veterans this Anzac Day?

Anzacs and veterans

The image conjured when I think of Anzac is that of rugged men muddied in trenches. They stare out at you from history books with toughness, resilience and bashful courage. Their knowing eyes defy their youthful faces. Anzac is the image of our past and provides the foundation for our present.

Photo by Mark Brake, The Advertiser

The image of a veteran, to me, has always been my grandfathers. Both served in World War II, one Army and the other Air Force. Their tales from Papua New Guinea, Britain and Burma were lost with their passing some years ago as neither shared their war stories when alive. As they reached the end of their lives their decrepit features mirrored those often flashed up on screens during Anzac Day — that of aged men with worn medals clanking across their now deflated chests. This vision of veteran is often shown with the dichotomy of youth; an iconic visual of the veteran’s actions and sacrifice as legacy to future generations. Their youthful faces passed onto the next generation but without the toughened glare of war.

I only had one fleeting moment of conversation with each of my grandfathers about their roles in World War II. War was rarely discussed. The first was with my grandfather who served in Papua New Guinea. I was 20 years old and had just completed Exercise Shaggy Ridge[2] (a sleep and food deprivation training exercise) as a cadet at the Royal Military College Duntroon. I was proud I had completed the arduous activity when others hadn’t. My grandfather paused in his response to my story, “Shaggy Ridge, yes, I patrolled in that area. I was so bloody scared of heights that I was more afraid to look down than I was of the Japs”. This ephemeral exchange of stories with a World War II veteran forever put my Army warries back in the box.

The second exchange was with my grandfather who served in the Air Force. I was about to deploy on my second tour of Afghanistan and was visiting him during pre-deployment leave. I chatted about my first deployment to Afghanistan and explained how my second deployment would be similar. During the conversation my grandfather disappeared. A couple of hours later he re-emerged holding two photographs. The first was a photograph of him in Afghanistan, taken while he was transitioning from Britain, where he had been a Night Intruder, to the campaign in Burma. “Afghanistan’s pretty rough, don’t trust the locals in a card game, they slit a chap’s throat when he didn’t pay his debt”. Handy advice. The second was a photograph of his Flight taken in Britain. For all bar two, the word ‘dead’ or ‘maimed’ was bluntly stated as he pointed at their youthful faces. I’m grateful one of the two was a younger image of my grandfather. With the words “war’s not the same anymore”, he disappeared again. This grandfather never attended Anzac Day.

I will never know the rest of my grandfathers’ stories but they will always be my image of a veteran and what I personally remember each Anzac Day. I cannot change my own stereotype image of Anzac and veteran. The textbook definition of a veteran may be simple but having a sense of being a modern veteran is a little more complicated when analysed against the past and ingrained stereotypes. The word veteran may never sit comfortably with me when pointed in my direction.

Who we are and who we are not

This morning the song ‘And the band played Waltzing Matilda’ rang out at my Regiment’s Dawn Service. Images of frail aged men once again flashed up on an overhead screen as the song struck the words:

“But the band plays Waltzing Matilda, and the old men still answer the call. But as year follows year, more old men disappear. Someday no one will march there at all.”[3]

But there will be someone. They are the contemporary veterans.

My thoughts coincide with reading James Brown’s book Anzac’s Long Shadow. Brown, a contemporary veteran himself, has eloquently captured the thoughts of many of us who are struggling to define ourselves against the Anzac stereotype.

Against another era of veteran, contemporary veterans do not face the Vietnam veteran’s adversity of returning to a nation that scorned their deeds. Our return has the support of the broader Australian community. We also have a blank canvas for our image. Brown points out that little is known in the general Australian community about the role of Australian Defence Force personnel in recent conflicts including East Timor, Iraq, Afghanistan and Solomon Islands.

Indeed serving personnel sometimes have misconceptions of veterans. During Anzac Day in 2011 I overheard an Australian Army soldier question why a member of the Royal Australian Navy was wearing an Afghanistan Campaign Medal. The tone suggested unworthiness of the honour; Afghanistan after all is a land-locked country. I was affronted by this comment as I had deployed to Afghanistan with Navy personnel who were Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technicians and Airforce personnel who were Joint Terminal Attack Controllers. If you know what these roles are, you will know how much admiration I have for their courageous service and contribution to the survivability of our team. As I explained to the soldier — even though medals look the same, each medal comes with its own story. Every contemporary veteran’s contribution should be valued without judgement.

Photo by Neil Ruskin, Afghanistan 2008

Similar stories are also presenting. Women are often judged to have only completed sedentary roles in Afghanistan and Iraq when there are many examples of the opposite. I have had young sappers tell me they have attended RSLs (Returned & Services Leagues) on Anzac Day and been told to move their medals to their right side as ‘don’t you know, medals awarded to a family member go on the right side of your chest’. Someone needs to remind these self-appointed hall monitors that the sentiment of the song ‘I was only 19’ applies not only to wars of bygone eras but also to our most recent conflicts. Having to justify your medal and convince people of the violence you faced in conflict because of your gender, age, service or corps is something I hope is a passing fad. This is a dangerous form of stereotyping that may become ingrained if our stories are not shared.

I don’t have a definition for the contemporary veteran or what mould we are made from. The lack of a stereotype may be our defining feature in the end. What I do know is that we own the image of the contemporary veteran because we are the contemporary veteran. We should not sit passively by and let others define who we are or who we are not. If we don’t own the image of the modern-day veteran then someone else will define it for us. This is clearly evident in the United States where tragic events inflicted by one have led to the stereotyping of many (see here, here and here). Brown calls for proactive participation of serving members in intellectual debate and the “fluid exchange of ideas and the honest and intelligent study of the past”[4]. Reflecting on our own contribution to the past and its meaning to our future may be a good place to start.

I caveat this call for action. There is no romanticised version of war, and men and women sign up to protect the general community and their loved ones from the horrors of war. It is difficult to share the horrors with people outside the military fold when it is those people who you served to keep the horrors from. Some contemporary veterans might not be ready to share. Like my grandfathers, the time may never come when the stories flow in general conversation. It is in this space that the voice of other veterans becomes ever more important.

To me the words veteran and Anzac conjure images of courageous men. Those men who returned home are now wearied by age and those who did not return home are forever suspended in youth. It is the spirit of Anzac and actions of veterans past that found the human qualities of the contemporary veteran — qualities of mateship, resilience and courage. They give meaning to our present and a reassurance in our human spirit for the adversities of the future. With this foundation and remembrance it is time for contemporary veterans to define our own image.

Major Clare O’Neill served in Afghanistan in 2006 and 2008. She is currently an Officer Commanding at the 3rd Combat Engineer Regiment, Australian Army.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Brown, James, Anzac’s long shadow: the cost of our national obsession, Redback, Collingwood, 2014, p. 96.

[2] Exercise Shaggy Ridge is named after operations in the forenamed area in Papua New Guinea in World War II, seehttp://www.awm.gov.au/units/event_347.asp

[3] Bogle, Eric, And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda, Larrikin Music Pty Limited, Sydney.

[4] Brown, p. 105.

Originally published at groundedcuriosity.com.