This novel shows us all the scars, reminds us of the broken parts within each of us, and the fragile world on which we try to ground ourselves. It is a reminder that whenever we return, we listen for the call of our name, for some hint that we matter, an echo of who we were, always and forever searching for ourselves across the years in a place we’ve lost along the way.

Out Jihad the Jihadi

In a lecture to field grade officers at the U.S. Army War College in 1981, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor described strategy as the sum of ends, ways and means; where ends are the objectives one strives for, ways are the course of action, and means are the instruments by which they are achieved.

All Hell Broke Loose: The U.S. Army and OPERATION TOENAILS

Few people, save avid students of the U.S. war in the Pacific, have ever heard of the small island group called New Georgia. Yet, in the summer of 1943, the island was the scene of some of the most brutal fighting of the entire war. It was on New Georgia where the 43rd Infantry Division experienced the highest number of cases of neuropsychiatric casualties (variably known as combat fatigue, shell shock, war neurosis, or post-traumatic stress disorder) casualties in any division during one operation in the entire war. For two of the three Army divisions on New Georgia, it was their baptism of fire, and one that they would never forget. While the capture of New Georgia was vital to the strategic and operational success of the Solomon Islands Campaign, the battle itself is a supremely interesting study in small-unit tactics, joint Army-Navy operations, logistics operations, and the trials of a joint command.

Green on Blue: An Interview with Elliot Ackerman

Green on Blue is the story of an Afghan child born to war, scarred by conflict, and driven by his enculturated need to respond to violence with violence. Aziz is his name. If you’ve served in Afghanistan and worked with the Afghan National Army, the National Police, or even if you’ve come across men who seem to live normal lives, you have probably met him; though it is unlikely that you understand what motivates him, what drives him to act, or what he fears.

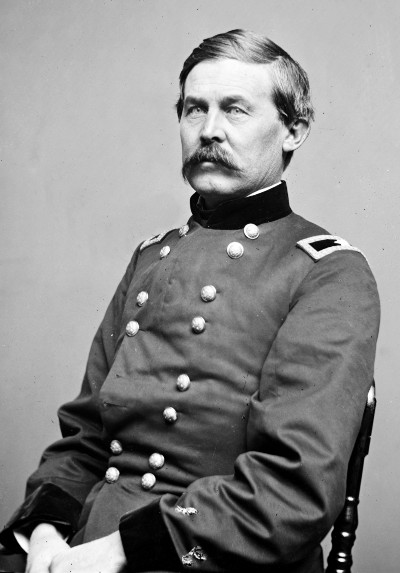

Architect of Battle: Buford at Gettysburg

Late in June 1863, the divisions of two great armies roamed Maryland and Pennsylvania. In retrospect, their confrontation at the crossroads of Gettysburg seems almost inevitable. However, the outcome of that confrontation was largely the work of one Union officer. This officer was born in Kentucky to a Democrat family. He would lead the First Division of Union Cavalry under orders to secure the crossroads in the vicinity of Gettysburg. How he executed these orders ensured the Union Army the best chance of victory in the upcoming battle.

He serves as a case-study in the theoretical and practical applications of tactics and strategy.

Buford as portrayed by Sam Elliot in the exceptionally detailed film Gettysburg.

Though General Buford is relatively well known to Civil War buffs, and has been played by Sam Elliot in the Gettysburg film, the extent of his contributions in the summer of 1863 remain more obscure. This is unfortunate. He serves as a case-study in the theoretical and practical applications of tactics and strategy. His leadership prior to the battle ensured that his troops were well prepared and ideally positioned for the Confederate advance. The leadership and defensive concepts he employed remain relevant today.

Buford’s objective on June 29th was to secure the town of Gettysburg for consolidation of the Army.

Buford studied cavalry tactics at Fort Crittenden, developing the idea of cavalry used as dismounted infantry in order to take advantage of terrain and provide concentrated firepower (Soodalter). Throughout the day on July 1st, Buford and his troops provided the Union Army with support and sufficient time to consolidate in the best defensible position available in the area. The“fish hook” on Cemetery Ridge was initiated with a layered defense beginning several miles away and collapsing back under the pressure of superior Confederate numbers.

Portrait of Brigadier General John Buford, Jr. (Wikimedia Commons)

Numerous roadways converged at Gettysburg. Four of these roads were hard-surfaced and therefore could facilitate more rapid movement of troops. Gettysburg was also near a railroad, presenting the potential for even greater mobility to whomever dominated the area (Longacre, p. 181–182).

Buford’s objective on June 29th was to secure the town of Gettysburg for consolidation of the Army. As such, Buford avoided prolonged combat when encountering a Confederate force (Longacre, p. 181). Another inconsequential clash occurred on the following day, June 30th, against a reinforced Confederate scouting party. Buford’s subordinate commanders viewed this as a positive sign, indicating the enemy’s unwillingness to press the issue. But Buford differed and correctly inferred that the lack of enthusiasm for fighting on the part of the Confederates indicated they had a better option than a hasty fight (Longacre, p. 182).

To confirm his suspicions, Buford conducted his own extensive reconnaissance of the terrain around the town. He talked with civilians and personally visited far-flung elements of his own forces, or pickets as they were called, to gather the most complete assessment of the enemy. He came to realize that a substantial force under General Hill was as close as 9 miles away (Longacre, p. 181–182, 184). Buford’s supervision of his forces on the eve of battle was comprehensive, and several aspects of what are today known as the US Army’s “troop leading procedures” were evident in his leadership example.

Buford set up his undersized element to force the Confederates to attack multiple superior defensive positions throughout the day.

He advised his men to notice campfires at night and the dust of approaching columns early in the morning. His men spread out in long, thin lines utilizing the available cover provided by the terrain. A small number of them had repeating rifles as well (Soodalter).

The defensive plan for the Union cavalry commander focused on the series of ridges surrounding the town. He determined that his initial defense would occur along McPherson and Seminary ridges to the north and west of the town, permitting his units to retreat and fight through the town and onto Cemetery Ridge if Confederate pressure was more than he and any Union reinforcements could handle (Longacre, p. 183). In this manner, Buford set up his undersized element to force the Confederates to attack multiple superior defensive positions throughout the day.

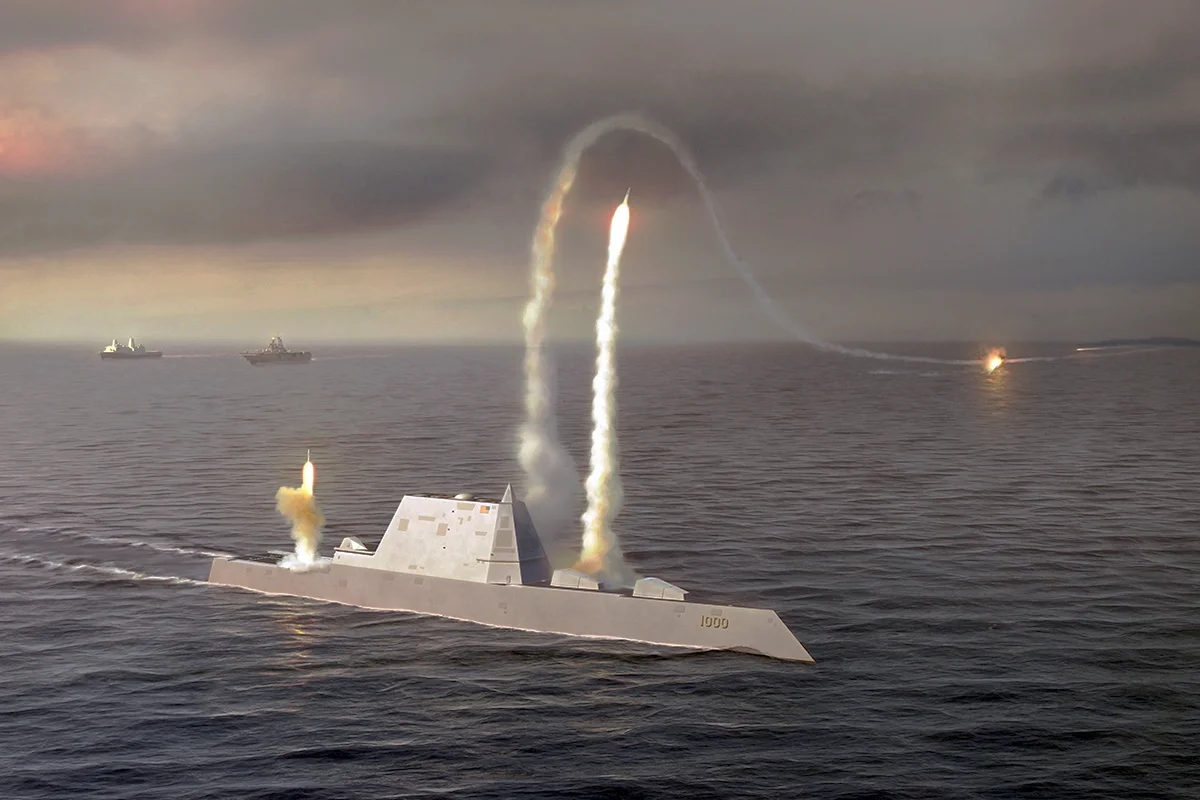

A modern rendering of a forward-thinking plan

Colonel Gamble was positioned in command of the western approach with a focus on McPherson’s Ridge and a reserve on Seminary Ridge. Gamble pressed an additional element 4 miles farther to the west on Herr Ridge, presenting a layered defensive on the most likely avenue of approach. The northern approach was under Colonel Devin’s command, who positioned forces along the compass points spanning northwest to northeast.

Battle commenced early on July 1st and Buford’s troops fought well against the Confederates. Confederate cavalry was not utilized effectively, enhancing the defensive advantages for the Union (Petruzzi). Late in the morning General Reynolds arrived to reinforce the troopers heavily engaged in vicinity of Gettysburg. While the Confederates succeeded in dislodging the Union Army from Seminary Ridge on the first day of battle, they could not press the issue effectively on Cemetery Ridge. Part of the defense of that position would be conducted by Buford’s troopers once again. As the Union Army regrouped on the ridge, Buford’s cavalry again exercised both mounted and dismounted maneuvers to confuse, impede, and distract the Confederates (Petruzzi).

General Buford died before the end of the war. While there are many important figures in the Civil War, he ranks among the most impactful even if not the most well-known. He designed, as much as any one person could, the Union’s most significant victory of the war.

Chris Zeitz is a veteran of military intelligence who served one year in Afghanistan. While in the Army, he also attended the Britannia Arms pub in Monterey. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Diplomacy from Norwich University. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of any U.S. Government agency.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The Future of Australian Land Operations

Editor’s Note: This article by Lieutenant General Angus Campbell originally appeared on The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s weblog The Strategist and is re-posted here with permission.

Lieutenant General Angus Campbell, Chief of the Australian Army (Courtesy of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute)

In my role to lead and prepare an Army to serve its nation, my career experience has developed in me a profound commitment to the value, indeed the necessity, of joint, inter-agency, coalition and allied operations, as the best and most sustainable way to pursue our nation’s interests.

This is because of the extraordinary skills, and potential for greatness, resident within our people, especially when we team across the boundaries of a diverse national and regional community.

The Army has an important contribution to make to this team, bringing many unique and useful capabilities. Important, although not always preeminent; context is all.

Unsurprisingly, as a Chief of Army, I am not an adherent to the false god of ‘high tech war’, that declares armies redundant, so banal is this analysis. Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster speaks in his usual compelling manner on this topic in his recent essay, Change and Continuity: the Nature of Future Armed Conflict.

Like all of you I dread war, and would welcome quick, clean, bloodless, decisive clashes, but when Shakespeare wrote, ‘Cry Havoc! And let slip the dogs of war’, he reminded us that these dogs, elsewhere alluded to as Famine, Sword and Fire, have a will of their own.

A war started is not necessarily a war ended; home by Christmas an illusion. War can slip readily out of the control of any of its belligerents. On land, at sea or in the air, cyber and space domains, war can all too easily spill over the convenient boundaries and timelines we so desire of it. An adversary on the defensive is an adversary looking for another domain in which to attack. This violent clash of wills doesn’t necessarily end when or how we choose.

In the deeply human and political tragedy that is war, in the last resort, violence often comes to a dramatic, exhausted or lingering close on land, because that is where we live.

However, this is no easy pass, the Australian Army should always be able to explain to the government and the people its role and utility, within a wider team effort, in defence of our nation and its interests.

Army’s priorities are:

- support to operations: because it’s why we exist;

- support to our wounded, injured and ill: because it’s the right thing to do and it rebuilds lives and human potential, for Army and Australia;

- modernisation of the Army: because I want to ensure our people have the best chance of coming home; and

- cultural renewal: because ethical soldiers working as a team are our most powerful weapon.

Today, I am going to concentrate on the third priority, modernisation. But before I do, let me make a few comments about the others.

Support to operations is obvious but has many deep implications. We fight joint, certify and deploy joint, command and control joint, increasingly employ joint doctrine and many of the most powerful asymmetric effects we can apply are uniquely joint. And these joint forces team with interagency, coalition and allied partners.

Recent adjustments to organisational and command arrangements within the ADF, announced in the First Principles Review, reflect the importance of strengthening the centre and enabling next steps in our joint development. I am very excited by the possibilities for the ADF of these changes and suspect historians will look back on this decade as the ‘tipping period’ in building joint forces characterised by deep environmental expertise.

The Australian Army’s 2014 Future Land Warfare Report, identified five trends that will likely shape future war: crowded, connected, lethal, collective, andconstrained, these trends are also converging. These are not simply big or pervasive changes — they broadly outline our future operating environment and will transform the ways we think, operate, cooperate and contribute as an army.

The Army doesn’t and shouldn’t have the luxury of choosing the type of war or security operation in which we might become involved. That is a decision for government. But we have to structure for and be competent in land joint war fighting, our unique contribution to national capability. Everything else we might be called upon to do is less difficult.

Today we see terrorism, intra-state conflict, great power positioning, state instability, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief all at play and all affecting Australia or its interests.

Because of life’s inherent uncertainties, I want the joint force to be as capable as we can afford, and I’m delighted at the quality of the air and naval forces Australia is building. We will always be stronger working together.

Our modernisation effort supports Army’s contribution to a broad range of operations. The following are three examples of issues we might consider in how Army does so:

First, the Army contributes to developing Australia’s key international security relationships, building confidence, and promoting common strategic understanding and interests. The Defence White Paper is likely to reinforce the importance of this ADF role and I look forward to working with our partners throughout the Indo Pacific Region, to align effort, build capacity and enhance cooperation.

Second, the Army contributes to deterring, and if required, defeating coercion of, or attacks on, Australia and its interests, particularly access to trade and commerce, the lifeblood of an island continent. This includes denying an enemy the freedom to operate within our extended approaches.

The ability of our Army to contribute to a strategic deterrence effect as part of our maritime strategy will increase with the development of an amphibious capability centered on two Landing Helicopter Dock ships. How Army, as part of a broader team, might support a maritime posture and the potential for the Army to contribute to access and area denial in the approaches to Australia needs also to be carefully considered.

Third, the Army makes a substantial contribution to the headquarters that might be expected to lead operations aimed at assisting or maintaining the stability of states within our extended approaches.

In the next 10 years, the Army will see substantial investment in protection and mobility, with projects focused on mission command systems, the introduction of protection from blast for our fleet of light, medium and heavy trucks and the replacement of our combat reconnaissance vehicle and armoured personnel carrier.

These projects combine to deliver vehicles that are more than replacements for their predecessors — they provide protected weapon systems, which are also a hub for communications, information, sustainment and fire support, enhancing the capacity of a ground force to absorb surprise and achieve tactical success in an era of democratised lethality.

Understanding the broad parameters of future land warfare environments, and the operating concepts applicable to them, can produce valuable insights to focus our development and enhance the Army’s strategic utility and tactical effectiveness in the defence of our nation and its interests.

Angus Campbell is Chief of the Australian Army. This post is an edited version of the speech from Lieutenant General Campbell delivered at the ASPI Army’s Future Force Structure Options Conference on 25 June 2015.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The Meaning in Belleau Wood

To really understand Marines, you need to know something about Belleau Wood. On June 6, 1918, the 4th Marine Brigade began its offensive into Belleau Wood in France, marking arguably the most significant day in the history of the U.S. Marine Corps. More Marines died that day than in the 143 years of Marine Corps history that had preceded it — combined. But it is not the magnitude of that sacrifice, or even the military objectives that were accomplished, that define the significance of that day; rather, it was the cultural impact that event had on the Marine Corps.

Less than a week earlier, a German attack, part of a series of offensives planned for 1918, had reached the town of Chateau-Thierry, just 55 miles northeast of Paris on the Marne River. Making it that far was a significant accomplishment for the Germans, who had finally broken free of the trenches, destabilizing a front that had been deadlocked for more than three years. The resources France and her allies had to contain the attack were strained, and the decision was made to bring in the 2nd Division of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), which had been in France training and preparing for a year, but had seen little combat. As the Americans took their positions to establish a new defensive line through which the retreating French 43rd Division would pass, far on the left, in rolling fields spotted with woods and small towns, was an aberration — the 4th Marine Brigade.

The Marines did not belong in an organization made up almost entirely of U.S. Army troops, but their commandant, Major General George Barnett, and the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, had worked hard to find a way to get them there, often by going around the War Department. Ultimately, two regiments’ worth of well-trained professional troops was not something the Army could afford to pass up, for it was struggling to quickly mobilize and deploy a massive force for war. The 5th and 6th Marine Regiments had been assembled from a blend of experienced Marine veterans and new recruits, and were ready to go. Arriving in France, they were assigned to the 2d Division, alongside the Army’s 3rd Brigade, and designated the 4th Brigade. They insisted on referring to themselves as the 4th Brigade (Marine).

“Retreat, Hell! We just got here!”

As the Marines advanced to occupy their lines, legend holds that streams of French soldiers were passing in the opposite direction, and one poilu urged them to join the retreat. The response from Captain Lloyd Williams, U.S. Marine Corps — “Retreat, Hell! We just got here!” — is oft-repeated in histories of the Marine Brigade and the remembrances of Marines, but his attitude was probably typical of the entire AEF. After a year in France, American soldiers and Marines had been chafing under the instruction and restrictions imposed by the European command. They were anxious to prove what they could do, and consummate their deployment to France.

The Marine Corps had placed a premium on marksmanship skills in recruit and pre-deployment training…

The Marines were well-suited to the position they were assigned to defend on June 2nd, in the rolling wheat fields northwest of Chateau Thierry. The Marine Corps had placed a premium on marksmanship skills in recruit and pre-deployment training in Quantico, Virginia, and now they had clear fields of fire. The Germans, who had been advancing in the vacuum left by the French retreat, ordered a halt when their leading elements began taking casualties from something they had not experienced in years of trench warfare: a growing volume of accurate long-range rifle fire. Approaching the limits of their logistical support, they began to dig in. The Germans anchored their defenses in a densely wooded hunting preserve, less than 300 acres in total size, that was directly across the fields from the 4th Marine Brigade — Belleau Wood.

After several days of small fights in the area, the Marine Brigade was ordered to counterattack into the woods on the 6th of June. The attack was hastily planned, and conducted without adequate reconnaissance or preparatory bombardment. Nonetheless, when the jump-off time arrived that evening, the Marines began advancing across the open wheat fields that separated their defensive positions from the dark woods ahead. Moving in four carefully-aligned rows of successive skirmish lines, the Marines were excellent targets for the German machine gun teams that had been emplaced in the woods. As the Marines were cut down in large numbers it became clear that they would pay a high price for inadequate planning by the small American staffs, and for the naïve tactics they had adopted. Despite these critical mistakes, they prevailed.

Sergeant Major Dan Daly after the Great War

Initially, the impetus to advance was reinforced by prominent leaders, such Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly, whose heroism in earlier campaigns had already been recognized with a Medal of Honor — twice. The inspiration of a figure like Daly, according to legend bellowing, “Come on you sons of bitches! Do you want to live forever?” was undoubtedly significant, but as the Marines advanced their companies were decimated, and their cohesion destroyed. The attack was reduced to small groups of Marines led by sergeants, corporals, and privates, and occasionally an odd surviving staff NCO or officer, but they still managed to reach the edge of the woods. There they began to secure a foothold, slowly destroying the German machine gun teams in a confusing melee amid the rocky terrain and dense vegetation.

It ultimately took three weeks to eject the Germans from Belleau Wood. Though the Marines were relieved by the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry for part of that time, in the end it was the Marine Brigade which finally cleared the woods, a fact proudly reported to 2nd Division Headquarters as “Woods now U.S. Marine Corps entirely.” In recognition of the feat, the French Sixth Army issued an order changing the name of the woods from the Bois de Belleau to the Bois de la Brigade de Marine.

It was a costly victory. The fourth Marine Brigade suffered about 4,000 casualties, approximately 55% of its total strength. Visitors to the American cemetery today at the north end of Belleau Wood, where the battle ended, will see the date “June 6, 1918” on a conspicuously large number of grave markers. There is also a beautiful chapel set into the hillside on the edge of the wood, and inside are the names of hundreds more men whose bodies were never found. For some Marines, the unit listed is “3rd Replacement Battalion,” in itself a testament to the chaos and savagery of that first day, when fresh men were rushed forward to the units fighting in the woods, and after that moment were lost even to history.

Belleau Wood, and the attack on the 6th of June in particular, was a defining moment for the Marine Corps. The significance of the event is not in the grossly exaggerated claim that the 4th Marine Brigade saved Paris, and by extension the rest of France, at its greatest moment of danger in World War I. The significance isn’t even in the number of Marines who gave the last full measure of devotion to the cause there, for the blood that was spilled in Belleau Wood wasn’t even a drop in the bucket. Sadly, it was more like a drop in the lake of blood that was the horror of the First World War.

The real significance of the 6th of June was that it established that Marines would prevail, regardless of cost, even when called to serve in places far outside of their traditional roles, and despite having every reason to stop and reconsider the wisdom of what they had been tasked to do. Belleau Wood provided a convincing narrative to reinforce not only Marines’ self-conception as elite warriors, but also a public image that further enhanced the Corps’ ability to find quality recruits and train them to high standards. Unfortunately, this elite image also came by means of implicit, if not explicit, comparison with the U.S. Army, contributing to a long pattern of interservice hostility.

The story of Belleau Wood reinforces everything Marines want to be reminded about themselves…

Culture is a powerful force within the U.S. Marine Corps, and the Corps’ remembered history is a vital part of its identity. The story of Belleau Wood reinforces everything Marines want to be reminded about themselves: that they have a tradition of superior commitment, that they are skilled marksmen, and that they can always count on small unit leaders and individual Marines to prevail, regardless of what may happen prior to the last hundred yards. In a more spiritual sense, Marines look to uphold the legacy of their forbearers, those who fought and died in Belleau Wood, as they would in later generations who fought in places like Tarawa, Iwo Jima, the Chosen Reservoir, Khe Sanh, and Hue. Less consciously, the Marines who uphold that legacy in places like An Nasiriya, Fallujah, and Now Zad, aren’t just preserving the legacy, but building upon it.

World War I helped to transform the Marine Corps organizationally from a more ad hoc, dispersed service to a modern, corporate, and deliberate body, but it was the crucible of Belleau Wood that proved what a Marine could be, and defined an ideal that Marines would identify with and strive towards ever since.

Image: U.S. Doughboys Handling an M1916 37mm Gun During the Battle of Belleau Wood, France, 1918 (via PhotosOfWar.net)

Shawn Callahan retired from the U.S Marine Corps in 2014 and is the author of Close Air Support and the Battle for Khe Sanh. He taught in the History Department of the U.S. Naval Academy and currently works in professional military education and is pursuing a PhD in History. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or any other agency, government or otherwise.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The Conflict That Changed America and Defined an Age

65 Years on from the Korean War

In a period full of anniversaries commemorating significant moments in the history of modern war, we find ourselves at the date of the Korean War’s start. It is a war I have spent considerable scholarly time with as a military historian. I have read the campaigns up and down the peninsula, tarrying particularly with the Marines and soldiers at Chosin, as well as giving due attention to the political machinations which surrounded it from near and abroad in the world. It is, in its details and grand narratives, a fascinating bit of history. Oft considered the forgotten war, the conflict in Korea is less overlooked than perhaps unseen, as it is in fact the primordial framework of the Cold War. Its many details are written into the terms of the era’s intensely fraught international competition. In the military strategy and tactics, national security conceptualizations, political constructs and policies which defined the period were evident in that war. Rather than looking at its contents, to within it as an event, this essay will take this moment to examine this transformational influence.

To begin, a brief sketch of the conflict in context sets the scene for this discussion. The years between the end of WWII and the start of the Korean War — and the Cold War as we know it — were marked by clear tensions among the great powers and uncertainty regarding the way forward across economic, political and military fronts. The potential for chaos lurked at key crossroads of humanity, and in China was manifested in the Civil War — remember they had been fighting since 1937. Within the American foreign policy, national security and defence sectors there were many ideas contending in an as yet to be defined soupy mess. Then, on the 25th of June, 65 years ago, North Korea rolled its forces across the diplomatic border separating the two regimes on the peninsula in a bid to rewrite the map and governance of the whole.

The conflict lingers to today, as yet unresolved.

The first panicked days would give way to international diplomatic action, the tottering initial military deployments growing eventually to a formidable army. Sinews and muscles of American war a bit atrophied from the intervention would rebound in short order. Near defeat at Pusan was mirrored by a hair’s breadth in the north in five short months. The fortunes of the war would ebb and flow from the over increasingly smaller geographical gains across the original border. As neither side could prevail the only answer was political. It took three years of fighting to little avail save death and destruction to recognize that truth only partially in an armistice. The conflict lingers to today, as yet unresolved.

If those are the broadest strokes of the war’s contents, what are the contours of its influence?

Unfortunately, NSC-68 also deranged aspects of American diplomacy.

The conflict, and its understood causes and terms, settled thinking on threats, risks and consequences in the emergent post-war international order. The outbreak of the war by way of military aggression by a Communist regime had a signal effect upon American perceptions of, and actions in, the world. It confirmed the ascendance of those who believed the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, West and East, democracy and communism was existential and dangerous. Out of this emerged the national security, foreign policy, and defense concepts of the Cold War. The defining framework of the era was promulgated with NSC-68. Assessing the Soviet and Communist threat as significant, opportunistic, and not unlike an active conflict, NSC-68 recommended an activist policy to confront the threat. Languishing a bit in D.C. after its publication within the government, the outbreak of hostilities half a world away gave the document’s perspective weight and authority to shape policy and strategy for nearly five decades.

Unfortunately, NSC-68 also deranged aspects of American diplomacy. First, it created the threat in absolute terms, allowing little room to imagine as non-threatening even the smallest hint of the ideology, and establishing the less than useful practice in American international relations of refusing or limiting diplomacy with states as a reasonable course of action. Furthermore, it mischaracterized the nature of relations between mentor and protégé states, overestimating the latter’s influence because it fit with the assumption of an international communist movement which centrally, by way of Moscow and perhaps Beijing, directed the actions of other states. Assuming communist mono-causality for tensions between states blocked out the recognition of the many factors which affect the interaction of states.

…the Cold War would be marked by the reliance upon the military component of American policy.

This national security strategy and supporting foreign policy ushered in with the Korean War was also bound by a preference for force. Committed to contain communist expansion anywhere as necessary, the Korean War particularly gave primacy to the military component of foreign policy. Mimicking North Korea’s recourse to force, the Cold War would be marked by the reliance upon the military component of American policy. Never before a significant peacetime military power, this tradition changed in the second half of the 20th century, which marked the greatest transformation of defense and foreign policy in the country’s relatively brief history. The strategic preferences of this militarized policy would shift, from a reliance upon nuclear weapons to a more balanced mix which included expanded conventional capabilities, but the essential belief in the strength and necessity of significant standing peacetime military forces remained unchanged throughout the Cold War.

President Bush’s “with us or against us” mantra continued the unyielding binary construct of the era.

Finally, it is worth considering whether these influences are limited to the Cold War. While the threat posed by communism seems a distant memory, many habits of the period linger and can be seen in the emergent construct of the “Global War on Terror.” President Bush’s “with us or against us” mantra continued the unyielding binary construct of the era. Deepening the effect of that, the threat posed by extremism is being written in absolute and existential terms, inspiring fear-based political support for the “conflict” and making more difficult the recourse to diplomacy with potentially troubling states. And having spent trillions of dollars on wars and military operations in the almost fifteen years since 9/11, there is no denying the continuation of an overwhelming preference for military solutions. The Cold War may have ended, but the Korean War’s influence remains.

Considering the Korean War in the context of its time and effects makes clear that while a human endeavor, war exceeds the control of its seeming masters. That war is political is little contested, but we too often define this by the agency of the actors. However, the active motivations and objectives which the actors create do not limit war’s political character. Rather, war in its own right as well is an agent of political change, as its influence across the human experience shapes the inputs and contexts for state and international politics.

Exceeding the will of the actors, the political effect of war is neither limited to its geography nor constrained by its scale. More importantly, its politics cannot be foreseen. This state of things is nowhere better exemplified than in the Korean War, a local conflict whose consequences should have been limited to the region, the ramifications and consequences of this relatively minor act were in excess of its any expectations.

This post was provided by Jill Sargent Russell, a PhD student at the King’s College London. Her dissertation is an ambitious look at subsistence, logistics, and strategic culture in the American military tradition, from the Revolutionary War to WWII. She holds an M.Phil. in Military History from George Washington University, an M.A. from Johns Hopkins SAIS, and was a West Point Fellow in 2004. Find her on Kings of War, Strife, Small Wars, and CCLKOW blogs.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Men of the 9th Infantry Regiment man an M26 tank to await an enemy attempt to cross the Naktong River, 3 Sep 1950. (Wikimedia)

#Reviewing Ghost Fleet: The Successes (and Shortcomings) of Informed Fiction and Strategy

Ghost Fleet is an enjoyable book. It is a fun book. What’s more, it is an insightful and prescient book, without forcing the reader to ever acknowledge that fact. Sure, it suffers, as many popular works do, with things that literary critics will nitpick over. But if there’s one thing that’s been made abundantly clear to me over the course of reading the work and discussing it with colleagues, it’s that Cole and Singer have accomplished the difficult feat of merging knowledge with storytelling, insight with invention.

Belleau Wood: A Defining Moment for 20th-Century Marines

The Bois de Bellau, or Belleau Wood was a serene hunting preserve flanked by wheat fields and situated about 50 miles from Paris. It was once deemed a “quiet sector” by American military commanders, but in early June 1918 it would be transformed into a hellish landscape littered with scores of dead and wounded. Along this mile-long stretch of hardwood forest located near an unassuming village in France, the World War I (WWI) Marine Corps would encounter what many consider to be a seminal battle in its history, and would be transformed from the amphibious infantry of its formative years to an organization more closely resembling the expeditionary force it is known as today.

Can Cooler Heads Prevail in U.S.-China Military Relations?

All is not right in U.S.-China relations. From Washington’s perspective, Beijing isn’t following the liberal internationalist script. For one thing, China’s “peaceful development” seems to have morphed into a full-throated, and ever expanding, assertion of the PRC’s sovereignty rights in the South China Sea. Moreover, the recent release of the People’s Liberation Army white paper confirms what has long been suspected: American hegemony is little appreciated in Beijing.

We Should All Carry Poetry (Part 2): An Interview with Stanton S. Coerr

Recently we reviewed Stanton S. Coerr’s (SSC) Rubicon: The Poetry of War on The Strategy Bridge (TSB). TSB also sat down with Coerr to learn more about him and to ask a few questions. Originally from North Carolina, Coerr grew up in a family of all women and attended school at Duke where he enrolled in the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC).

We Should All Carry Poetry (Part 1): #Reviewing Rubicon

War poetry has been on a decline. There is an abundance of literature about Afghanistan and Iraq and endless raw video footage. History has never been recorded more completely than today. In this world, however, no voice rises above the media-created noise to make us pause, breathe, think, or — for a moment — shiver. Imagine if one night, on prime-time, we got just two minutes to hear a poem such as Siegfried Sassoon’s “Suicide in the Trenches.”

China’s Military Strategy: Challenge and Opportunity for the U.S.

China recently published its new Military Strategy. Within this strategy China must be given credit for clearly articulating its version of the “Monroe Doctrine” for the Asia-Pacific region and its desire to no longer play second fiddle to the U.S. globally. Unlike the current U.S. national security strategy, China’s strategy is more narrowly focused on securing its near abroad (the first island chain) while also expanding its military reach to secure its interests globally. Meanwhile, the U.S. faces a complex global landscape, and must confront threats perceived and real emanating from multiple angles while managing significant fiscal constraints.

What Successful Strategists Read

The bottom-line is that there already exists a long list of lists advising strategists on what they should read. At best, the analysis presented here provides one more list to consider. To remain open-minded, hopefully a strategic thinker would never limitthemselves to any list. Nevertheless, the hope is that individuals find the results of this survey valuable as they chart their course of self-study and reflection, wherever that may take them.

Fishing on the Narrative River

Recently, Jason Logue spent some time on the Bridge looking over the river “Narrative.” Jason cast a line into the rushing current catching a basket full of tasty ideas that he shares with anyone who stops at his campfire. If Jason will allow, I’d like to join him by casting my own line into teeming waters with hopes of reeling in a catch worthy of a campfire fish tale.

#Reviewing Lessons from the Gun Doctor

Armstrong is able to return a spotlight on Admiral William Sims, an innovative naval leader often overshadowed by the subject of Armstrong’s first book, Alfred Thayer Mahan. Armstrong shares the story of how a young Lieutenant redefined the Navy’s approach to warfare by applying lessons learned from others to his own crew and reporting the improved results up his chain of command and to anyone who would listen, including the President of the United States and naval enthusiast, Theodore Roosevelt.

Lines in Shifting Sand

The scars of the Arab Spring, the fall of several dictators, and renewed western relations with Iran have widened the eyes of the traditional monarchies in the Middle East, and they are taking calculated steps to ensure that their economic and power systems are secure from any future threats. As the U.S. invites the GCC members to participate in the gathering at Camp David, and as new Middle East strategy recommendations call for a more “management” focused approach, an opportunity to refine our interactions has appeared on the horizon.

Unfinished Business

On the heels of the 40th anniversary of America’s departure from Vietnam, a reflection on the past is appropriate. In honor of this occasion I found myself revisiting David Halberstam’s Best and the Brightest. Multiple dissertations could be written over individual components of the book, including Halberstam’s detailed portraits and backgrounds of the key decision-makers involved in run-up and execution of the Vietnam War. For the purposes of brevity and clarity, this paper focuses on two related problems noted throughout the book: the inherent limitations of foreign militaries in counter-insurgencies, and the challenges associated with selecting and training local security forces.

In Defense of Programs: Surviving The Drawdown

The drawdown is upon us. Both the base budget and the overseas contingency operation funding lines are getting smaller. This is forcing Department of Defense (DoD) components to make hard decisions on which programs they want to fund. These hard decisions are informed and influenced by the efforts of strategists, cost assessors, budgeters, congressional affairs personnel, program evaluators, and others who do similar work. If DoD components want to survive, and possibly thrive during a drawdown, they need to invest in and reward the work of strategists, cost assessors, budgeters, congressional affairs personnel, and program evaluators as they are DoD’s Program Defenders.