Late in June 1863, the divisions of two great armies roamed Maryland and Pennsylvania. In retrospect, their confrontation at the crossroads of Gettysburg seems almost inevitable. However, the outcome of that confrontation was largely the work of one Union officer. This officer was born in Kentucky to a Democrat family. He would lead the First Division of Union Cavalry under orders to secure the crossroads in the vicinity of Gettysburg. How he executed these orders ensured the Union Army the best chance of victory in the upcoming battle.

He serves as a case-study in the theoretical and practical applications of tactics and strategy.

Buford as portrayed by Sam Elliot in the exceptionally detailed film Gettysburg.

Though General Buford is relatively well known to Civil War buffs, and has been played by Sam Elliot in the Gettysburg film, the extent of his contributions in the summer of 1863 remain more obscure. This is unfortunate. He serves as a case-study in the theoretical and practical applications of tactics and strategy. His leadership prior to the battle ensured that his troops were well prepared and ideally positioned for the Confederate advance. The leadership and defensive concepts he employed remain relevant today.

Buford’s objective on June 29th was to secure the town of Gettysburg for consolidation of the Army.

Buford studied cavalry tactics at Fort Crittenden, developing the idea of cavalry used as dismounted infantry in order to take advantage of terrain and provide concentrated firepower (Soodalter). Throughout the day on July 1st, Buford and his troops provided the Union Army with support and sufficient time to consolidate in the best defensible position available in the area. The“fish hook” on Cemetery Ridge was initiated with a layered defense beginning several miles away and collapsing back under the pressure of superior Confederate numbers.

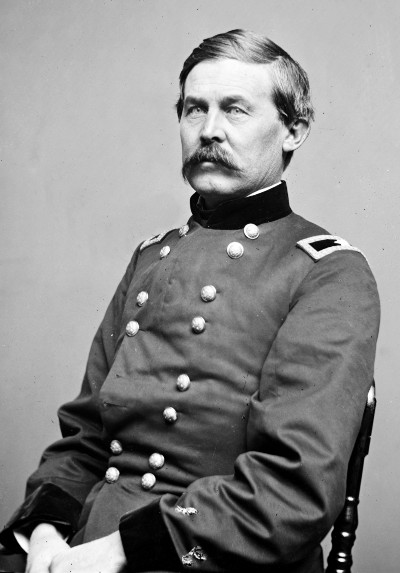

Portrait of Brigadier General John Buford, Jr. (Wikimedia Commons)

Numerous roadways converged at Gettysburg. Four of these roads were hard-surfaced and therefore could facilitate more rapid movement of troops. Gettysburg was also near a railroad, presenting the potential for even greater mobility to whomever dominated the area (Longacre, p. 181–182).

Buford’s objective on June 29th was to secure the town of Gettysburg for consolidation of the Army. As such, Buford avoided prolonged combat when encountering a Confederate force (Longacre, p. 181). Another inconsequential clash occurred on the following day, June 30th, against a reinforced Confederate scouting party. Buford’s subordinate commanders viewed this as a positive sign, indicating the enemy’s unwillingness to press the issue. But Buford differed and correctly inferred that the lack of enthusiasm for fighting on the part of the Confederates indicated they had a better option than a hasty fight (Longacre, p. 182).

To confirm his suspicions, Buford conducted his own extensive reconnaissance of the terrain around the town. He talked with civilians and personally visited far-flung elements of his own forces, or pickets as they were called, to gather the most complete assessment of the enemy. He came to realize that a substantial force under General Hill was as close as 9 miles away (Longacre, p. 181–182, 184). Buford’s supervision of his forces on the eve of battle was comprehensive, and several aspects of what are today known as the US Army’s “troop leading procedures” were evident in his leadership example.

Buford set up his undersized element to force the Confederates to attack multiple superior defensive positions throughout the day.

He advised his men to notice campfires at night and the dust of approaching columns early in the morning. His men spread out in long, thin lines utilizing the available cover provided by the terrain. A small number of them had repeating rifles as well (Soodalter).

The defensive plan for the Union cavalry commander focused on the series of ridges surrounding the town. He determined that his initial defense would occur along McPherson and Seminary ridges to the north and west of the town, permitting his units to retreat and fight through the town and onto Cemetery Ridge if Confederate pressure was more than he and any Union reinforcements could handle (Longacre, p. 183). In this manner, Buford set up his undersized element to force the Confederates to attack multiple superior defensive positions throughout the day.

A modern rendering of a forward-thinking plan

Colonel Gamble was positioned in command of the western approach with a focus on McPherson’s Ridge and a reserve on Seminary Ridge. Gamble pressed an additional element 4 miles farther to the west on Herr Ridge, presenting a layered defensive on the most likely avenue of approach. The northern approach was under Colonel Devin’s command, who positioned forces along the compass points spanning northwest to northeast.

Battle commenced early on July 1st and Buford’s troops fought well against the Confederates. Confederate cavalry was not utilized effectively, enhancing the defensive advantages for the Union (Petruzzi). Late in the morning General Reynolds arrived to reinforce the troopers heavily engaged in vicinity of Gettysburg. While the Confederates succeeded in dislodging the Union Army from Seminary Ridge on the first day of battle, they could not press the issue effectively on Cemetery Ridge. Part of the defense of that position would be conducted by Buford’s troopers once again. As the Union Army regrouped on the ridge, Buford’s cavalry again exercised both mounted and dismounted maneuvers to confuse, impede, and distract the Confederates (Petruzzi).

General Buford died before the end of the war. While there are many important figures in the Civil War, he ranks among the most impactful even if not the most well-known. He designed, as much as any one person could, the Union’s most significant victory of the war.

Chris Zeitz is a veteran of military intelligence who served one year in Afghanistan. While in the Army, he also attended the Britannia Arms pub in Monterey. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Diplomacy from Norwich University. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of any U.S. Government agency.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.