Reconsideration of U.S. grand strategy is critical in the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine alongside rising tensions with China. Rebecca Lissner’s Wars of Revelation makes a compelling argument that past U.S. military interventions have played an important role in shaping U.S. grand strategy.

#Reviewing Some are Always Hungry

Military officers may not be inclined to reach for a book of poetry to bolster their understanding of warfare, but important lessons can be drawn from seemingly unusual sources. And while the Chief of Staff of the Air Force Professional Reading Program has been expanded to include cinema, photography, and even TED Talks, poetry in book or singular form appears to have never made the decades-old list. Similarly, poetry does not seem to be included on sister service recommended reading lists. Despite this, there is a place for poetry somewhere in the military leader’s piles of literature, history, and leadership books, one that puts a little heart into the science of war.

#Reviewing Korea: The War Before Vietnam

In Korea: The War Before Vietnam, Callum A. MacDonald writes with short, sharp clarity. The precision of his writing does not take away from necessary details or the importance of the Korean War in international history, especially for those involved in that conflict. The book is driven by a narrative told through official documents, robust secondary sources, and scholarship developed over nearly 35 years.

Balance with the Political End State: Case Studies from Korea and Vietnam

In conclusion, war is not limited nor is it total. War, and by extension, warfare, is situationally unique. Each instance is shaped through internal and external political factors, as it always has been. Understanding those factors and successfully balancing them with the appropriate means and ways to prosecute war is the defining characteristic of successful warfare.

Attacking in a Different Direction: #Reviewing On Desperate Ground

Sides’ history highlights lessons from one of America’s few large-scale conventional conflicts in the post-World War II era. Sides’ story highlights the risk of miscalculating a foreign power’s intention to intervene in a conflict, the American predilection to over-rely on technology in warfare, and the enduring importance of experienced leadership in combat.

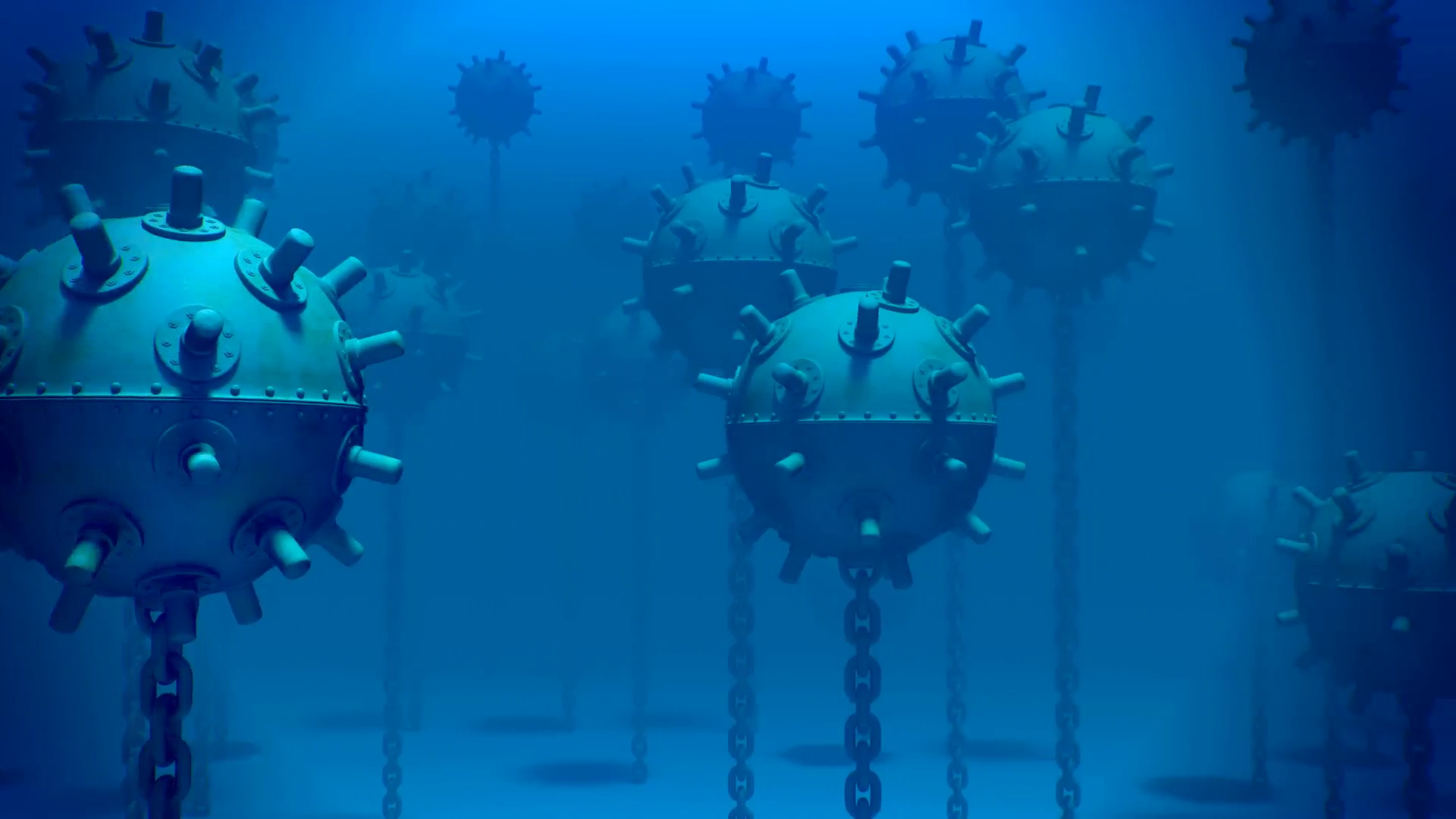

Sea Mines in Amphibious Operations

It is vital that alongside expensive amphibious assault ships a navy invests in mine warfare equipment and training, otherwise, the procurement of an amphibious capability will have been in vain. Naval mines are not going anywhere soon...nor will amphibious operations if they lack the ability to deal with sea mines.

North Korea: Time for a "Normal" Strategy?

The agenda for normalizing U.S.-Pyongyang relations should be modeled after the incremental U.S.-Hanoi approach, yet also take advantage of the momentum created by the April 27 summit between President Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong Un. While the summit produced few detailed plans, both leaders agreed in principle to pursue a permanent peace treaty. This now presents a natural opportunity for the U.S. to support South Korea by setting aside previous ambitions for regime change and championing efforts to turn the 1953 armistice into a peace agreement. Progressive steps would then follow a similar multi-year process used with Vietnam. Pursuing this methodology offers a viable conduit for changing the dynamics on the peninsula and in the region, while Kim Jong Un is provided security as well as access to the resources needed to lead his desired modernization efforts.

A Pyongyang Spring? Not So Fast

Whilst the diplomatic de-escalation of tensions in early 2018 is a welcome affirmation of Churchill’s observation that ‘jaw jaw is better than war war,’ the apparent concessions that North Korea has offered are not particularly damaging to Pyongyang’s interests. The array of concessions that Kim Jong Un has offered do not meet the standard of costly signals. North Korea has, on multiple occasions, offered concessions to U.S. and South Korean interests, only to renege on them with embarrassing haste. It is thus necessary to go beyond a superficial reading of DPRK’s apparent concessions.

Failure to Communicate: U.S. Intelligence Structure and the Korean War

Intelligence at all levels is an art form. Sources, corroborating or contradicting information, unknowns, and delays in time all result in varied levels of analytical confidence. Information coming from different means, methods, and areas requires a functioning structure to ensure senior national leaders have the best information to make the decisions. While strategic intelligence drives operations and national goals, military decision-makers—especially in combat zones—rely on tactical intelligence to help win battles. For the Department of the Navy, “tactical intelligence support is the primary focus of naval intelligence.”[1] Marine Corps intelligence also focuses almost exclusively on the tactical level to support Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) maneuvers since tactical intelligence is, “the level of intelligence Marines need, generate, and use most often.” When strategic missteps occur, tactical intelligence can provide a needed capability to keep front-line forces winning, creating breathing room for new strategic plans. A functioning intelligence structure encompassing all levels of intelligence is needed to enact this goal.

#Reviewing Success and Failure in Limited War

Strategic performance is strongly affected by the state’s information management capabilities. Top policymakers must have the ability to understand the environment in which they are acting (outside information) and how their national security organizations are behaving in that strategic environment (inside information). Strategic risk assessment is based on an understanding of the opponent’s strengths and weaknesses, the challenges and opportunities present in the international environment, and the capability of the state to act in a purposeful way along multiple lines. Without sound outside and inside information, risk assessments will suffer, as will the quality of strategy.

#Reviewing Success and Failure in Limited War

In the Information Institution Approach, Bakich gives critical importance to whether or not key decision makers have access to multi-sourced information and whether the information institutions themselves have the ability to communicate laterally. When information is multi-sourced and there is good coordination across the diplomatic and military lines of effort, Bakich predicts success. When information is stove piped and there is poor coordination, he predicts failure. Where the systems are moderately truncated, Bakich expects various degrees of failure depending on the scope and location within the state’s information institutions.

The Legacy of Task Force Smith

The mission at hand was daunting. A light infantry task force faced a larger conventional force bearing down on their positions in a foreign land. The division leaders were combat veterans of past years of global conflict, while the soldiers were mostly young and new troops yet to be hardened by combat.

The Conflict That Changed America and Defined an Age

65 Years on from the Korean War

In a period full of anniversaries commemorating significant moments in the history of modern war, we find ourselves at the date of the Korean War’s start. It is a war I have spent considerable scholarly time with as a military historian. I have read the campaigns up and down the peninsula, tarrying particularly with the Marines and soldiers at Chosin, as well as giving due attention to the political machinations which surrounded it from near and abroad in the world. It is, in its details and grand narratives, a fascinating bit of history. Oft considered the forgotten war, the conflict in Korea is less overlooked than perhaps unseen, as it is in fact the primordial framework of the Cold War. Its many details are written into the terms of the era’s intensely fraught international competition. In the military strategy and tactics, national security conceptualizations, political constructs and policies which defined the period were evident in that war. Rather than looking at its contents, to within it as an event, this essay will take this moment to examine this transformational influence.

To begin, a brief sketch of the conflict in context sets the scene for this discussion. The years between the end of WWII and the start of the Korean War — and the Cold War as we know it — were marked by clear tensions among the great powers and uncertainty regarding the way forward across economic, political and military fronts. The potential for chaos lurked at key crossroads of humanity, and in China was manifested in the Civil War — remember they had been fighting since 1937. Within the American foreign policy, national security and defence sectors there were many ideas contending in an as yet to be defined soupy mess. Then, on the 25th of June, 65 years ago, North Korea rolled its forces across the diplomatic border separating the two regimes on the peninsula in a bid to rewrite the map and governance of the whole.

The conflict lingers to today, as yet unresolved.

The first panicked days would give way to international diplomatic action, the tottering initial military deployments growing eventually to a formidable army. Sinews and muscles of American war a bit atrophied from the intervention would rebound in short order. Near defeat at Pusan was mirrored by a hair’s breadth in the north in five short months. The fortunes of the war would ebb and flow from the over increasingly smaller geographical gains across the original border. As neither side could prevail the only answer was political. It took three years of fighting to little avail save death and destruction to recognize that truth only partially in an armistice. The conflict lingers to today, as yet unresolved.

If those are the broadest strokes of the war’s contents, what are the contours of its influence?

Unfortunately, NSC-68 also deranged aspects of American diplomacy.

The conflict, and its understood causes and terms, settled thinking on threats, risks and consequences in the emergent post-war international order. The outbreak of the war by way of military aggression by a Communist regime had a signal effect upon American perceptions of, and actions in, the world. It confirmed the ascendance of those who believed the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, West and East, democracy and communism was existential and dangerous. Out of this emerged the national security, foreign policy, and defense concepts of the Cold War. The defining framework of the era was promulgated with NSC-68. Assessing the Soviet and Communist threat as significant, opportunistic, and not unlike an active conflict, NSC-68 recommended an activist policy to confront the threat. Languishing a bit in D.C. after its publication within the government, the outbreak of hostilities half a world away gave the document’s perspective weight and authority to shape policy and strategy for nearly five decades.

Unfortunately, NSC-68 also deranged aspects of American diplomacy. First, it created the threat in absolute terms, allowing little room to imagine as non-threatening even the smallest hint of the ideology, and establishing the less than useful practice in American international relations of refusing or limiting diplomacy with states as a reasonable course of action. Furthermore, it mischaracterized the nature of relations between mentor and protégé states, overestimating the latter’s influence because it fit with the assumption of an international communist movement which centrally, by way of Moscow and perhaps Beijing, directed the actions of other states. Assuming communist mono-causality for tensions between states blocked out the recognition of the many factors which affect the interaction of states.

…the Cold War would be marked by the reliance upon the military component of American policy.

This national security strategy and supporting foreign policy ushered in with the Korean War was also bound by a preference for force. Committed to contain communist expansion anywhere as necessary, the Korean War particularly gave primacy to the military component of foreign policy. Mimicking North Korea’s recourse to force, the Cold War would be marked by the reliance upon the military component of American policy. Never before a significant peacetime military power, this tradition changed in the second half of the 20th century, which marked the greatest transformation of defense and foreign policy in the country’s relatively brief history. The strategic preferences of this militarized policy would shift, from a reliance upon nuclear weapons to a more balanced mix which included expanded conventional capabilities, but the essential belief in the strength and necessity of significant standing peacetime military forces remained unchanged throughout the Cold War.

President Bush’s “with us or against us” mantra continued the unyielding binary construct of the era.

Finally, it is worth considering whether these influences are limited to the Cold War. While the threat posed by communism seems a distant memory, many habits of the period linger and can be seen in the emergent construct of the “Global War on Terror.” President Bush’s “with us or against us” mantra continued the unyielding binary construct of the era. Deepening the effect of that, the threat posed by extremism is being written in absolute and existential terms, inspiring fear-based political support for the “conflict” and making more difficult the recourse to diplomacy with potentially troubling states. And having spent trillions of dollars on wars and military operations in the almost fifteen years since 9/11, there is no denying the continuation of an overwhelming preference for military solutions. The Cold War may have ended, but the Korean War’s influence remains.

Considering the Korean War in the context of its time and effects makes clear that while a human endeavor, war exceeds the control of its seeming masters. That war is political is little contested, but we too often define this by the agency of the actors. However, the active motivations and objectives which the actors create do not limit war’s political character. Rather, war in its own right as well is an agent of political change, as its influence across the human experience shapes the inputs and contexts for state and international politics.

Exceeding the will of the actors, the political effect of war is neither limited to its geography nor constrained by its scale. More importantly, its politics cannot be foreseen. This state of things is nowhere better exemplified than in the Korean War, a local conflict whose consequences should have been limited to the region, the ramifications and consequences of this relatively minor act were in excess of its any expectations.

This post was provided by Jill Sargent Russell, a PhD student at the King’s College London. Her dissertation is an ambitious look at subsistence, logistics, and strategic culture in the American military tradition, from the Revolutionary War to WWII. She holds an M.Phil. in Military History from George Washington University, an M.A. from Johns Hopkins SAIS, and was a West Point Fellow in 2004. Find her on Kings of War, Strife, Small Wars, and CCLKOW blogs.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

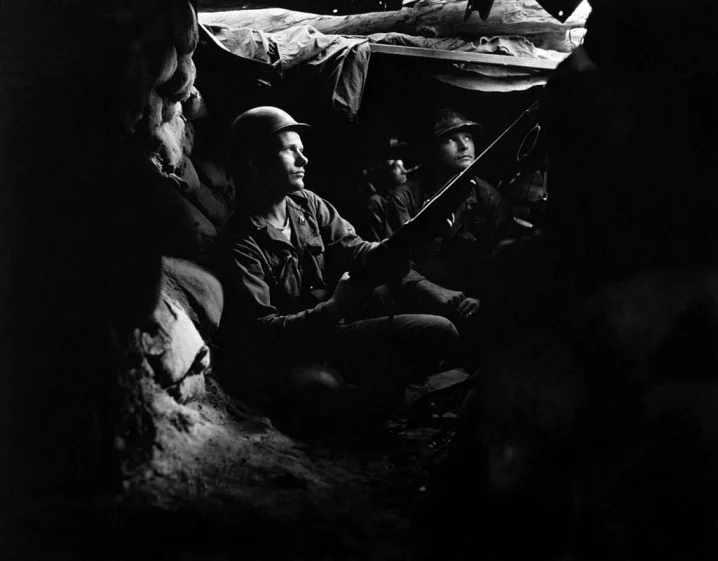

Header Image: Men of the 9th Infantry Regiment man an M26 tank to await an enemy attempt to cross the Naktong River, 3 Sep 1950. (Wikimedia)