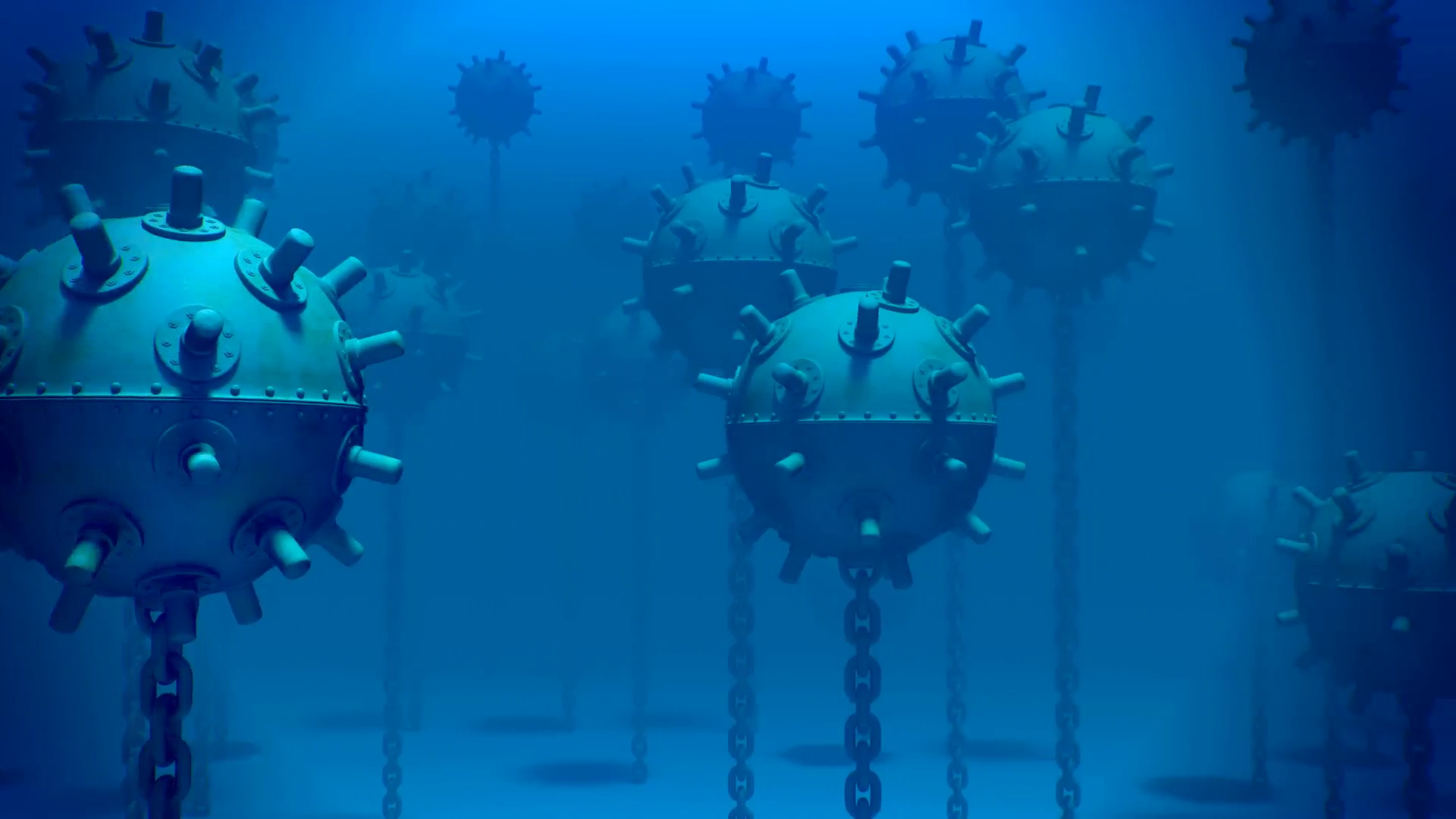

Procuring expensive amphibious assault ships is utterly worthless if a navy’s mine warfare capacity is token. For a navy considering amphibious operations, investing in the necessary mine clearing capabilities is an absolute must. However, adjusting doctrine to increase the target priority of an enemy’s mine laying capabilities may offset the necessary investment mine warfare. In the past, neglecting mine warfare has impeded a number of amphibious operations and come at the expense of achieving operational goals. This article shall explore the effect of sea mines in the examples of the Landing at Wonsan and Gulf War before examining strategies for negating the effect of sea mines to amphibious operations. With technologies such as active, mobile and swarming sea mines mine becoming available, mines still present the most pervasive and cost-effective threat to amphibious operations.

With technologies such as active, mobile and swarming sea mines mine becoming available, mines still present the most pervasive and cost-effective threat to amphibious operations.

Sea mines are widely available—twenty nations export them—and underwater improvised explosive devices can be easily fashioned.[1] Since World War II, they have sunk or damaged more U.S. Navy ships than air or missile attacks.[2] To be effective and minimise losses, minesweeping in a non-permissive environment—whether by diver, ship, or helicopter—requires naval and air superiority. Sea mines require neither; they are a set-and-forget weapon. At Normandy, in spite of Allied-controlled of the area of operation, mines damaged or sunk 43 allied vessels.[3] Sinking that many ships in a modern context may make an amphibious assault untenable. Sea mines offer a cheap early warning system by virtue of the time-intensive process of mine clearance. Thus, mines grant nations a considerable and cost-effective arrow in their defensive quiver.

A General Patton tank (M-46) leaving through the bow doors of USS LST-914 during the invasion of Wonsan, Korea, 2 November 1950. (U.S. Navy Photo)

As a corollary of the post-World War II demobilisation, the number of minesweeping capabilities decreased. The reduction in mine warfare ships, equipment, and experienced personnel would combine in the Korean War to demonstrate the importance of maintaining a sufficient mine warfare capability.[4] In anticipation of an amphibious assault, North Korea laid approximately 3,000 magnetic mines in the Port of Wonsan in three weeks.[5] UN forces removed 224 of these 3,000 to clear a channel for their amphibious assault. Clearing these 224 mines delayed the operation by five days, resulted in four ships sunk, and inflicted over 200 casualties.[6] While mine warfare ships and training are expensive, North Korea demonstrated that utilising them is not. Defusing a mine at sea will likely always be more costly and time intensive than deploying it. Whilst the cost asymmetry of mine warfare can undoubtedly be detrimental to operations—de-mining ships and personnel may take away money that could have otherwise been spent elsewhere—it is the effect of mines on operational goals that is most harmful. The use of mines in Wonsan did not merely delay the assault; it restricted the logistical capacity of the port and reduced the distance inland naval gunfire support could be delivered.[7]

“We have lost command of the sea to a nation without a navy, using weapons that were obsolete in World War I laid by vessels that were used at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ.”

The landing at Wonsan demonstrated the benefit of sea-mines beyond area denial. The minesweeping gave a clear warning to the defenders as to the location of the coming assault. Without sufficient mine-sweeping resources to feint and threaten a different location, defenders could concentrate their forces. The time delay offered by sea-mines allowed the enemy to reinforce the location or withdraw their forces. While minimizing the available space for amphibious landings reduces logistical capacity, it increases operational pause and escalates the potential of failure on the beachhead. Comments made by Rear Admiral Smith, commander of the amphibious task force at Wonsan, demonstrate the asymmetry in mine warfare: “We have lost command of the sea to a nation without a navy, using weapons that were obsolete in World War I laid by vessels that were used at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ.”[8] It showed a defender could delay or dissuade amphibious assaults with an investment many times less than the cost of mine clearing operations.

A close-up view of a crack in the hull of the Aegis-guided missile cruiser USS Princeton, damage sustained when the vessel struck an Iraqi mine on 18 Feb 1991. (CW02 Bailey/U.S. Navy Photo)

In addition to the asymmetry in investment, the Gulf War would demonstrate that without the necessary outlay in mine warfare capabilities an amphibious assault capacity could be rendered moot. The onward march of technology had done little to change the mine warfare equation by the Gulf War. Iraq deployed over 1600 mines between the Al-Faw Peninsula and the Kuwait-Saudi border, in a density that was nearly impenetrable.[9] Because of this, perhaps the Iraqis should have realised the two regimental landing teams deployed in the Gulf were little more than a feint.[10] However, mine detonations damaged the USS Princeton and USS Tripoli, halting mine-clearing operations and removing the amphibious threat.[11] The Iraqis failed to take advantage of the sea-mines as an early warning system; several Iraqi divisions could have been re-deployed or used as reserves, able to return to the coast if the assault occurred. The four to six days required for the U.S. to clear the mines given the resources on hand would have provided the Iraqis with ample warning, while clearing the mines in 24 hours would have taken twice the total number of minesweepers the U.S. Navy possessed.[12] Estimated casualties from mines alone for the Marines’ amphibious operation were 3000-5000.[13] Such a casualty rate would render an operation untenable. A near-peer opponent, combining dense, high-technology minefields with effective shore-based anti-ship missiles, air defences, and airpower could significantly impede the amphibious threat with little seaborne investment.

Several considerations come into play when addressing the early warning and delaying effect of sea-mining for amphibious operations. Possessing sufficient mine clearing capacity to divide those resources and conduct a feint may grant significant strategic utility. Disguising commercial shipping as minesweepers may afford some countries a degree of this utility. Unmanned underwater systems may also grant an ability to clandestinely find and neutralize sea mines and thus prevent alerting an adversary to a navy’s intentions.[14] Should this not be possible, clearing a channel as quickly as possible is a priority. Limiting the enemy’s ability to reinforce the assault location is paramount given the importance of superiority in manpower and firepower to successful assaults.[15] Interdicting this reinforcement with missiles and airpower would be of considerable importance. Minimizing the time delay between the commencement of minesweeping operations and landings would be of critical importance in minimizing an adversaries time to concentrate forces. Expanding the cleared channels would also be crucial to ensure sufficient reinforcement and resupply capability to minimise operational pause.

A number of conclusions follow for navies wishing to preserve their amphibious advantage. First, a navy must not neglect maintaining the necessary mine warfare capability required to supplement amphibious operations. Secondly, to negate the asymmetry of mine warfare, navies should be ready to prioritise enemy mine laying capabilities over other targets. Countering the mine threat to amphibious operations would best occur at the source, since sea mines cannot delay operations or inflict casualties if they are not deployed. Such prioritisation would make considerable sense for navies with nominal mine warfare capabilities, or those reliant on freedom of movement and rapidity of operations to be successful amphibiously. Establishing area denial bubbles in potential landing locations may prevent adversaries from laying minefields where a navy desires to land. Finally, navies must invest in unmanned surface and underwater systems that can be deployed from any type of ship and screen for mines ahead of a ship's movement. Of the fifteen U.S. ships damaged by sea mines since World War 2, just four were dedicated minesweeping vessels. By distributing and potentially increasing mine warfare capabilities amongst an amphibious fleet, unmanned systems grant the potential of increasing an amphibious fleet’s de-mining potential without significant investment in dedicated mine warfare platforms. They further reduce the risk of casualties or damage to ships with the potential to delay or dissuade amphibious operations. Amphibious operations also require shallow water in potentially non-permissive environments to be de-mined. Unmanned underwater systems offer the potential to undertake this mission while also being able to feedback hydrographic data to the amphibious fleet.[16]

A demolition charge detonates 1,500 meters from the Avenger-class mine countermeasures ship USS Scout. (Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Joshua Lee Kelsey/U.S. Navy Photo)

Conversely, states wishing to deploy sea-mines defensively should focus on the capacity to deploy as many as possible as quickly and surreptitiously as possible. Deployment of mines from submarines is a capability that would allow a navy to deploy mines covertly and gain a head start in laying mines before an adversary can prevent it. In a non-permissive environment, this could present a significant advantage. Active autonomous mines could automatically deploy themselves underwater, as well as granting the potential for minefields that can move location to prevent long-range connectors outflanking them.[17] Mobile mines also allow for mines to actively attack de-mining ships or personnel as well as filling in any cleared channels in minefields.

Adversaries faced with a significant asymmetry in force are likely to defer to sea mines to counter amphibious operations. The threat of an amphibious capability will be rendered moot if a navy does not possess the necessary minesweeping capacity or does not disable an adversaries mine laying capacity. It is vital that alongside expensive amphibious assault ships a navy invests in mine warfare equipment and training, otherwise, the procurement of an amphibious capability will have been in vain. Naval mines are not going anywhere soon...nor will amphibious operations if they lack the ability to deal with sea mines.

Josh Abbey is a research intern at the Royal United Services Institute of Victoria. He is studying a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Melbourne, majoring in history and philosophy. He is fascinated by military history and strategy, international security and analysing future trends in strategy, capabilities and conflict.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Underwater Mines (VideoBlocks)

Notes:

[1] Scott C. Truver, "Taking Mines Seriously: Mine Warfare in China’s Near Seas," Naval War College Review 65, 2 (2012): 31.

[2] National Research Council, Naval Mine Warfare: Operational and Technical Challenges for Naval Forces (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2001), 2.

[3] Ibid, 74.

[4] Stephen Dwight, “A Study of the United States Navy's Minesweeping Efforts in the Korean War,” MA Diss., (Texas Tech University, 1993), 1.

[5] Malcolm W. Cagle and Frank A. Manson, The Sea War in Korea (Maryland: United States Naval Institute, 1957), 144.

[6] Lieutenant Commander Paul McElroy, The Mining of Wonsan Harbor, North Korea in 1950: Lessons for Today's Navy (Maryland, Virginia: Marine Corps War College, 1999), 30.

[7] Ibid, 14.

[8] Ocean Studies Board, National Research Council, Oceanography and Mine Warfare (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000), 12.

[9] Lieutenant Commander James F. Ball, The Effects of Sea Mining Upon Amphibious Warfare (Kansas: United States Army Command and General Staff College, 1992), 118.

[10] Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Composto, Desert Storm and the Amphibious Assault (Newport: Naval War College, 1991), 12.

[11] Captain Bruce F. Russell, The Operational Theatre Mine Countermeasure Plan: More Than a Navy Problem, (Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies, 1995) 17-19.

[12] Ball, Effects of Sea Mining upon Amphibious Warfare, 121.

[13] Ibid, 118.

[14] Naval Studies Board, Naval Mine Warfare Operational and Technical Challenges for Naval Forces (Washington, D.C: National Academy Press, 2001), 79-80.

[15] Michael O'Hanlon, "Why China Cannot Conquer Taiwan," International Security 25, 2 (2000): 54.

[16] “Find, Fix, Identify, Engage: How Today's AUV Technology Can Compress The Mine Warfare Kill Chain,” John Rapp, CIMSEC, accessed August 4, 2018, http://cimsec.org/find-fix-identify-engage-todays-auv-technology-can-compress-mine-warfare-kill-chain/16729. Thomas Brown, et al., Next generation mine countermeasures for the very shallow water zone in support of amphibious operations (Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School, 2012).

[17] “Swarming Sea Mines: Capital Capability?,” Zachary Kallenborn, CIMSEC, accessed June 15, 2018, http://cimsec.org/swarming-sea-mines-capital-capability/33836 .