Apocalyptic anticipation thriving in a sectarian bloodbath is the focus of this text, which was released alongside a biography of the group’s leader available from Brookings. Despite the claims of a recent anonymous author, there is nothing “bewildering” or “alien” about the Islamic State.

What Did Osama bin Laden Say? #Reviewing The Audacious Ascetic

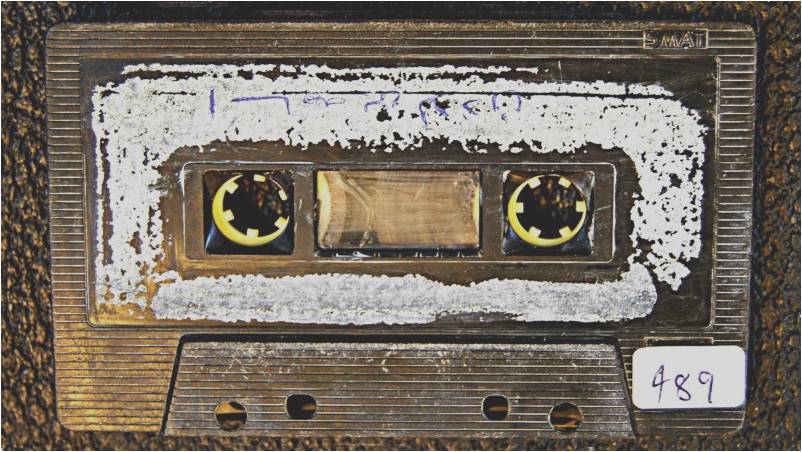

Dr. Flagg Miller is a linguistic anthropologist who has spent nearly a decade cataloging, translating, and interpreting a treasure trove of over 1,500 audio recordings of bin Laden and other jihadist leaders recorded between 1997 and 2001. The tapes served as an audio library for visitors to bin Laden’s Khaddar home and show the wear and tear of being listened to by his visitors.

#Reviewing the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham: What, Who, Where, When

#Reviewing The Air Force Way of War

Much has been written about the transformation of the United States Air Force between the Vietnam War and Operation DESERT STORM. In his classic book Sierra Hotel, C.R. Anderegg documented the revolution in training that occurred at the Fighter Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base during this era, led by the so-called “Fighter Mafia” of Air Force legends such as John Jumper, Ron Keys and Moody Suter. Steve Davies opened the door to the secret MiG program known as “Constant Peg” that occurred during the same time period in his book Red Eagles, while former Red Eagles Squadron Commander Gail “Evil” Peck gave his unique perspective on this historically significant squadron in his book America’s Secret MiG Squadron.

#Reviewing No Place to Hide

From the first pages of No Place to Hide, I found myself transported back to Iraq. I walked between the rows of sandbags and around the puddles of filth as I made my way through long rows of modular housing units. Eventually I popped out near the courtyard fence, the one that separated the pool area from the palace itself. I shuffled my feet across the wet patio and made my way to the fifty-five gallon drum filled with concrete, mounted at an angle, and pointed the barrel of my empty nine millimeter Beretta pistol into the three inch opening. I pulled back the slide, checked the empty chamber for the one hundredth time, and let it spring back into position. As I made my way into the chow hall to wash my hands again and dry them with something that felt like wet toilet paper, I tried to ignore the dull feeling deep inside.

#Reviewing The Air Force Way of War: Making the Machine Human

"“The four-ship of F-15C Eagles raced across the sky at thirty thousand feet. The flight lead, call sign Death-1, focused on his radar, looking for enemy aircraft in the vicinity. He also knew those enemy aircraft were looking for him.”Brian Laslie’s pulse-racing preface to his new book, The Air Force Way of War: U.S. Tactics and Training After Vietnam, grips the reader’s attention right away, bringing this reader back to the excitement and youthful nervousness of flying over the Nellis ranges..."

#Reviewing From Deep State to Islamic State: War, Peace, and Mafiosi

Increasingly, authors are delving into the nebulous connections between autocrats, apparatchiks, and terrorists. Some have a tendency to view these connections as either the continuation of domestic politics or the instrumentalization of radicals in lieu of raising and equipping capable armies. These perspectives are heavily invested in the concept of the state — more invested in that concept than the individuals analyzed. Westerners of diverse backgrounds tend to latch on to simple narratives when seeking to explain what is really a complex and jumbled mess of motivations Misunderstanding the rise of the state security mafias could have significant consequences. Jean-Pierre Filiu has admirably attempted to correct these interpretations.

#Reviewing Ghost Fleet: Go back! It's a trap!

Let it be said, I am a fan of Singer’s work in general. Rather than spending your time in the narrative nightmare that is the Ghost Fleet, however, I recommend reading his other work (Corporate Warriors, Wired for War, and Cybersecurity and Cyberwar are excellent) and foregoing this foray into fiction. You’ll trade the human power of narrative — even poor narrative has power — for the difficulties of nonfiction, but you’ll also see nearly every idea Singer and Cole offer in this disastrous novel … and I promise you’ll be better for having spent your time more wisely than I did.

Caution: Read Instructions Before Deploying Troops! #Reviewing The Unraveling

The Unraveling demonstrates how badly a war can go when a nation does not apply all of its resources to the problem. The U.S. lacked diplomats trained and intimately knowledgeable of Iraq to work alongside the military in rebuilding what we broke. In some areas, military leaders performed the civil affairs duties successfully but in others, the military was the wrong tool to use. America, after each war swears there will never be another, but memories fade and the ramifications of going to war and sending troops into battle are replaced with the idea that the U.S. has the answer for every problem. Maybe having a staff pacifist is the answer?

#Reviewing Ghost Fleet: The Successes (and Shortcomings) of Informed Fiction and Strategy

Ghost Fleet is an enjoyable book. It is a fun book. What’s more, it is an insightful and prescient book, without forcing the reader to ever acknowledge that fact. Sure, it suffers, as many popular works do, with things that literary critics will nitpick over. But if there’s one thing that’s been made abundantly clear to me over the course of reading the work and discussing it with colleagues, it’s that Cole and Singer have accomplished the difficult feat of merging knowledge with storytelling, insight with invention.

We Should All Carry Poetry (Part 1): #Reviewing Rubicon

War poetry has been on a decline. There is an abundance of literature about Afghanistan and Iraq and endless raw video footage. History has never been recorded more completely than today. In this world, however, no voice rises above the media-created noise to make us pause, breathe, think, or — for a moment — shiver. Imagine if one night, on prime-time, we got just two minutes to hear a poem such as Siegfried Sassoon’s “Suicide in the Trenches.”

#Reviewing Lessons from the Gun Doctor

Armstrong is able to return a spotlight on Admiral William Sims, an innovative naval leader often overshadowed by the subject of Armstrong’s first book, Alfred Thayer Mahan. Armstrong shares the story of how a young Lieutenant redefined the Navy’s approach to warfare by applying lessons learned from others to his own crew and reporting the improved results up his chain of command and to anyone who would listen, including the President of the United States and naval enthusiast, Theodore Roosevelt.

#Reviewing “U.S. Naval Institute On Naval Command”

Naval Command is clearly aimed at officers who aspire to or are preparing to assume command. However, it can also serve as a valuable resource for junior officers who wish to better understand the lens through which their commanding officers view their own responsibilities. In several instances, Cutler distilled lengthy contributions down to tightly presented summaries of the salient details. This skillful editing yields a 194-page book that is neither intimidating in scope nor size. While Naval Command can be read cover to cover, it may be best used in the traditional “wheel book” sense — a professional reference manual that an officer can return to time and again for insight and guidance.

#Reviewing Buzzell

Now comes Thank You for Being Expendable: And Other Experiences, a collection of occasional essays that date back as far as 9/11 — Buzzell was on the ground in New York City to watch the Twin Towers fall — and as recent as a 2015 review of American Sniper. Many chapters date from the years Buzzell bounced around the country researching Lost in America. Once more we see Buzzell enchanted by aspects of American culture untouched by prosperity and respectability.

Anti-Hero Narration of War: #Reviewing “Thank You for Being Expendable”

Colby Buzzell’s anthology of short stories, Thank You For Being Expendable, is the punk rock alternative to Service Academy and/or Ivy League-educated military officer GWOT-memoirs. Buzzell is a hard drinking, chain smoking, enlisted Stryker Combat Brigade infantryman who not only fought in Mosul during one the deadliest years of Operation Iraqi Freedom but also witnessed firsthand the events of 9/11 in New York City.

The Specialist Speaks: #Reviewing “Thank You for Being Expendable”

Teaching Tacticians: #Reviewing Naval Tactics

How do you win? Strategists determine what must be done and why. Operational planners devise the when and where. Tacticians are left the most daunting question: How? Though tactical prowess cannot save a poor strategy, the success of both strategy and operational planning frequently ride on tactical achievement. Yet, unlike strategy, tactics are infrequently discussed. Many tactics hide behind layers of classification, and training commands train their students to memorize and execute “proven” “pre-planned responses.” In the exigencies of combat, muscle memory is critical, but discussion of how those tactics were proved is often lost.

These problems are particularly acute for naval tactics. No two navies have fought a major fleet engagement in more than seventy years, and those who would command ships in battle must wait until the twilight years of their careers before they can coordinate multiple units. The U.S. Naval Institute’s new Naval Tactics “wheel book” helps fill a yawning gap.

Unlike much rote tactical training, the book highlights the role of thinking and experimentation, particularly qualitative, historical study.

Edited by Captain Wayne Hughes, USN (ret.), Naval Tactics includes tactical essays from the past 110 years. Hughes highlights directly applicable tactical principles, such as continuing importance of tactical formations, as well as the drivers of tactical change while providing subtle comment on some of the most important challenges facing the U.S. Navy today. Many essays remain as relevant today as they were when written, 30 or more years ago. Unlike much rote tactical training, the book highlights the role of thinking and experimentation, particularly qualitative, historical study.

One might expect that Hughes, an operations researcher, would emphasize quantitative methods in developing and testing new tactics. He argues, however, that tactics require a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis, or art and science, as he terms them: “The value of science is illustrated by operations analysis and quantitative calculations while the role of art is illustrated by the unique insights of great leaders who could reduce complex considerations into clear and executable battle plans.”[1] The books emphasis on qualitative analysis is striking. Of its thirteen essays, only the oldest, a selection from Bradley Fiske’s “American Naval Policy,” contains any discussion of quantitative calculations.

This imbalance likely targets the intended audience, few of which will have operations analysis experience and many of whom may have no prior tactical education. Even so, it seems significant that as a tactical primer the book focuses on the art rather than the science of tactics, particularly when that art is presented as the stuff of “unique insights of great leaders.” Such insights are as likely the product of preparation and study as of inborn ability. The book’s existence presupposes one can learn to think tactically.

Hughes frequently omits the tactical conduct of a battle from his selections, focusing instead on the preparation for battle or the development of the tactics it would see employed.

In pursuit of that goal, the book clearly emphasizes rigorous historical study in combination with thought experiments. Eight of Hughes’s thirteen elections detail historical battles or the history by which a tactic was developed. Two of the remaining essays (the opening and closing) layout thought experiments. Surprisingly, Hughes frequently omits the tactical conduct of a battle from his selections, focusing instead on the preparation for battle or the development of the tactics it would see employed. This choice emphasizes the contingency of outcomes and further supports the importance of principles of thought.

Ultimately, the commander must be able to act and react in the moment of battle. In the words of Frank Andrews, when “two pieces of war hardware … are roughly on a par, … the victor will be determined only by the outcome of the clash between the minds and the wills of the two opposing commanding officers.”[2] Here, numerical analysis breaks down, for while aggregate probabilities may suggest what generally works, the commander must determine the best course of action for his or her particular situation. Some officers may be born with talent, but for most no substitute exists for practice and study in developing the perspective and judgment required for making tactical decisions.

Without a doubt, combat experience teaches tactical thinking most effectively, but mistakes are costly and opportunities thankfully rare. Exercises provide the next best option. Although, Navy devotes more time to exercises today than it did when Bradley Fisk called for competitive “sham battles” to improve tactical performance over 100 years ago, the chances for practice remain few.[3] Only the study of past battles, the principals they illuminate, and the discussion of the questions they stir, remains as an inexpensive and widely accessible option.

Operators will always highlight experience when finding ways to win, but too often today’s Navy eschews the investment in study that can prepare officers to take full advantage of operational opportunities. The selections and stories in Naval Tactics provide an excellent and engaging place to begin such study.

Erik Sand is an active duty U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer stationed at the Pentagon. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Wayne P. Hughes Jr., ed., The U.S. Naval Institute on Naval Tactics, U.S. Naval Institute Wheel Books (Annapolis, MD: naval Institute press, 2015), xii.

[2] Hughes, Naval Tactics, 53.

[3] Hughes, Naval Tactics, 108.

#Reviewing ISIL's Playbook

A Look at Managing Savagery:

The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Uma will Pass

ISIL has a textbook. Its actions thus far have so closely followed this textbook, it is astounding. The textbook is translated into English, and not particularly difficult to read and understand. Suspend your disbelief. Maybe ISIL is more than a random group of irreverent murderous thugs taking advantage of ungoverned space. Maybe the counter-ISIL strategy is lacking.

Managing Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Uma Will Pass was written by Islamic strategist Abu Bakr Naji in 2004, translated in 2006 by William McCants who is a leading scholar of militant Islam. It describes a three phase approach to establishing an Islamic state. The theory behind ISIL’s entrenchment in Iraq and Syria is accurately described in the decisive operation, managing savagery. But don’t be misled by the terminology. “Savage” refers to non-Muslims and moderate Muslims. The violence ISIL displays is an effort to “manage” the “savages.” It is a disciplined program to establish Salafism, and its members are not undisciplined criminals any more than the Nazi Gestapo in the 1930s, or Stalin’s security apparatchiks in the 1950s.

The book is highly prescriptive, more Jominian than Clauswitzian, and equally brilliant. The author describes a version of mission command under the heading “art of management” providing guidance for who should lead, how to make decisions, how to delegate authorities, when to engage in combat, when to use violence against a population, Sharia law and justice, and how to gain and maintain the initiative. He describes formidable obstacles to establishing an Islamic state and what to do about them, such as: countering infiltration of adversaries, countering Western messaging, increasing the lack of administrative cadres, how to minimize members changing loyalties, and how to reverse the decreasing numbers of “true believers.”

The three phased approach bears striking similarity to US operational doctrine, which begins with shaping operations, then decisive combat operations, and then transition to peace.

It is not a coincidence that Americans now characterize themselves as “war weary,” because they are victims of a deliberate strategy of exhaustion.

The first phase, according to the author, is “vexation and exhaustion.” It can be compared to the colonial American Continental Army’s approach to combat against the British Empire in the 1700s, or any number of successful asymmetric conflicts throughout the centuries. In such cases, the weaker opponent must wear down the stronger opponent until it can achieve some level of parity. The author provides a number of historic examples, all of which seem to pit Islamic warriors against non-believers. The most compelling is the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, where the Mujahedeen successfully wore down the Red Army. The book describes setting strategic “traps” for Americans in Iraq, causing the US to plunge further and further into an inescapable quagmire. It is not a coincidence that Americans now characterize themselves as “war weary,” because they are victims of a deliberate strategy of exhaustion.

This strategy is in fact an extension of Usama Bin Laden’s strategy of limited warfare employed by Al Qaeda. Abu Bakr Naji assumed that pulling Americans deeper into the Iraq war would eventually lead to the collapse of the United States because he inaccurately attributed the collapse of the Soviet Union to Mujahedeen operations in Afghanistan. Therefore, its strategy of exhaustion against the US was only partially successful. Although it succeeded in making Americans war weary, it has yet to achieve its desired goal, which is the collapse of the United States.

The second phase of establishing an Islamic state, “managing savagery,” is the decisive operation and best describes current ISIL efforts. The focus of the second phase is to remove elements it believes as cancerous to a pure Islamic society. Although Western media sources tend to characterize ISIL’s penchant for dramatic executions as irrational, the source of its violent behavior is rational because it follows a logical purpose motivated by a combination of fear, honor, and interest. Although brutal and abhorrent, it is rational in the same sense that the Rwanda Genocide in 1994, or Nazi extermination of Jews, followed a logic and purpose. Garnering very little attention in Western media, ISIL also forces the population to continue working; requiring bakeries and administrative offices to remain open. It patrols the streets to ensure markets and retail stores are not mobbed or looted. It appoints local villagers as leaders. It establishes a school system to “properly educate” the next generation of Salafi Muslims. It establishes courts and a system of justice, beginning with a public square in which public executions may be conducted. Compared to Nouri Al Maliki’s Iraq, or Bashir Al Asad’s Syria, much of the Sunni population find ISIL governance more attractive.[1]

The third phase focuses on expanding the Islamic state and provides guidance on establishing affiliations, franchises, and alliances. The book even explains which countries and regions are ripe for an Islamic revolution. Particularly noteworthy, the author rejects the boundaries of existing Middle Eastern countries as western colonial fabrications. When he refers to “Syria” for example, he is referring to a population that likely spans into Turkey and Iraq. His theory of expansion seems to be theoretically similar to the Marxist expansion of communism, in the sense that a global revolution establishing a pure Salafi Islamic state is inevitable.

Overall, the strategy described in Managing Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Uma will Pass is a brilliant and artful theory of achieving a very difficult end state with extremely limited means. Since it is the strategy of our adversary, this conclusion may be difficult to accept. Even more difficult to accept is the necessity to re-think the counter-ISIL strategy in the context of ISIL’s text book. Specifically, will the counter-ISIL strategy destroy ISIL, or feed into the establishment of an Islamic state? If the strategy is similar to Communist expansion, would a closer study of George Kennan’s containment strategy outlined in his “Long Telegram” be more appropriate? In a region where Western democracy is not understood and largely rejected, what alternatives to Assad and Maliki can the U.S. provide that ISIL is not providing?

Harry York is a strategic planner in the Pentagon. He holds a Master’s Degree from the Army School of Advanced Military Studies and a Bachelor’s Degree in Russian from the University of Washington. He has multiple deployments to both Iraq and Afghanistan as both an aviator and an operational planner. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[i] Mr. Hassan Hassan, co-author of the best selling book ISIS: The Army of Terror and whose home town is in ISIL held Syria, stated in a Pentagon lecture on 11 March 2015, “Some people like that ISIL establishes law and order. Sunni populations do not want Shia militias operating on their soil, even to “free” them from ISIL. Therefore, ISIL is gaining support despite military defeats. It is strategically winning in part because there is no sustainable governance replacing it, and moderates are becoming weaker. In addition, no one says what will replace ISIL. Some say ISIL is crumbling (referencing a Washington Post Article by Liz Sly), but it is not.

#Reviewing Airpower Reborn

Airpower Reborn: The Strategic Concepts of John Warden and John Boyd. John Andreas Olsen, ed. Naval Institute Press, 2015.

Airpower Reborn: The Strategic Concepts of John Warden and John Boyd is a compilation of strategic thought by six well-respected airpower thinkers. Through its examination of airpower theory and theorists, the book navigates a maze of contentious but important topics regarding the relationship between airpower and military strategy. In this five-chapter anthology, the authors dissect airpower’s historical successes and failures while engaging the theorists, advocates, and zealots who have attempted to communicate its value to a sometimes apathetic if not outright hostile audience. But more important than the book’s examination of airpower theory is its exploration of military strategy in general.

Anyone who enjoys challenging the status quo will find the attempt to reboot modern strategic thought refreshing, if not overdue.

Airpower Reborn is a book for many audiences. Airpower thinkers will enjoy the balanced discussion of their field. Airpower critics will find contentious claims to explore, discuss, and dispute. Strategists of all types will find an engaging, contemporary look at military strategy through the lens of those who believe airpower has fundamentally changed the character of war. Plus, anyone who enjoys challenging the status quo will find the attempt to reboot modern strategic thought refreshing, if not overdue.

The editor, John Andreas Olsen, is one of the most globally respected authors on the subject of contemporary airpower. He is a Colonel in the Royal Norwegian Air Force currently serving in the Norwegian Ministry of Defence. His excellent bibliography includes A History of Air Warfare, Air Commanders,and John Warden and the Renaissance of American Airpower.

In his introduction, Olsen offers a modern and balanced approach to the history of airpower thought. He pokes at the zealots who oversold airpower in its infancy and who dug an intellectual hole out of which today’s airpower thinkers are still trying to climb. However, Olsen also takes aim at some of airpower’s staunchest critics as he introduces the central and controversial thesis of the book: the ground-centric paradigm of strategy which equates taking and holding territory with winning a war is not only outdated, but has been the root cause of repeated strategic failure by Western nations over the past fifty years.

He then steps through a brief introduction of each chapter on his way to his recommendation for all countries to establish a “dynamic and vibrant environment for mastering aerospace history, theory, strategy, and doctrine.” Coincidentally, the Chief of Staff of the US Air Force recently brought together a cadre of influential and respected airpower thinkers from the US, the UK, and France, including some of this book’s contributors, in order to foster exactly the intellectual environment Olsen recommends. Great minds think alike, I suppose…

He pokes at the zealots who oversold airpower in its infancy and who dug an intellectual hole out of which today’s airpower thinkers are still trying to climb.

As the book is an edited compilation of independent but related essays, it suffers from a few gaps and overlaps common to such works. Yet, individually, each chapter presents a cohesive argument.

In Peter Faber’s chapter, “Paradigm Lost: Airpower Theory and its Historical Struggles,” he argues that before the mid-1980s, airpower theorists and advocates tried to overthrow the existing, land-centered paradigm of war — and failed. Faber explains the bases of this paradigm, from Machiavelli to Clausewitz and beyond, then describes and fairly critiques the efforts of early airpower advocates who often oversold or misunderstood the role of airpower.

“The Enemy as a Complex Adaptive System: John Boyd and Airpower in the Postmodern Era,” is Frans Osinga’s introduction to John Boyd in a mere 44 pages — a feat any Boyd acolyte will find unimaginable. Be prepared, however. This heady discussion of Boyd and his work is not for the faint-hearted (or the intellectually distracted) as it explores complex adaptive systems, philosophy, cognitive sciences, and of course, Boyd’s famous OODA loop. According to Osinga’s thesis, Boyd contributed to more than just airpower theory; his work has had a fundamental impact on theories of war, conflict, and even business strategy.

USAF aircraft of the 4th Fighter Wing (F-16, F-15C and F-15E) fly over Kuwaiti oil fires, set by the retreating Iraqi army during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. (USAF photo by Tech. Sgt. Fernando Serna)

“Smart Strategy, Smart Airpower” is a readable discussion by the brilliant and controversial John Warden, who argues airpower has been limited by an outdated paradigm of war. Warden also claims the old paradigm (essentially the same land-centric paradigm Faber described) is the cause of the West’s modern war troubles. Instead, he advocates influencing leadership, processes, and infrastructure before attacking fielded forces — his Five Rings Model. To answer the critics who tritely simplify this model to: “decapitate (bomb) enemy leadership to win the war,” Warden’s well-written chapter clarifies a number of misconceptions by explaining the nuances of his model in contemporary and historical contexts.

Alan Stephens’ “Fifth Generation Strategy” claims that for fifty years, the West has failed to achieve strategic success in expeditionary wars because it clings to first generation strategy — a Napoleonic view of warfare which bases strategic success on taking and occupying territory with large armies in foreign countries.

Two F-22 Raptors fly over the Pacific Ocean. (USAF photo by Master Sgt. Kevin J. Gruenwald)

In response, Stephens presents a modern alternative he calls fifth generation strategy — a combination of Boyd and Warden’s thought that 1) sees tempo and strategic paralysis as levers of strategic success and 2) argues achieving military objectives does not always lead to the desired strategic outcome. Unfortunately, Stephens undermines his own work with a number of political and parochial jabs which may draw the ire of some readers, regardless of their merit

Achieving military objectives does not always lead to the desired outcome.

The book closes abruptly with “Airpower Theory” by Colin Gray in which he offers an airpower theory in the form of twenty-seven dicta — formal pronouncements — somewhat disappointingly plucked directly from Chapter Nine of his book Airpower for Strategic Effect. That this list of dicta was essentially copied-and-pasted into Airpower Reborn left me wanting, if not disappointed. Gray’s prolific and thoughtful airpower bibliography indicates he could have put forth a more tailored contribution to the book. For the interested reader, I recommend exploring his other works including Understanding Airpower: Bonfire of the Fallacies.

Still, it has been decades since the last significant contribution to airpower theory. Given the shifting character of war and rapid technological change, a solid modern airpower theory will be required for the West to achieve strategic success in future conflicts. But Airpower Reborn is not a work of airpower theory; it is a work about airpower theory and its relationship to military strategy. This book will fuel a much-needed and overdue discourse on airpower theory and military strategy.

This persistent (and mistaken) belief that modern airpower theory rests solely on century-old airpower prophecy says more about our failure as airpower advocates than it does about airpower critics.

Airpower Reborn is both an anthology of airpower thought and a call to action. Today, there is a great need for contemporary airpower thought. This book is a commendable attempt to spark discussion about airpower theory and strategy. Also, Olsen’s call to action is both timely and relevant, since the words “Douhet was wrong” still ring from people’s mouths. This persistent (and mistaken) belief that modern airpower thought rests solely on century-old airpower prophecy says more about our failure as airpower advocates than it does about airpower critics. It is our job to effectively develop and communicate modern strategic airpower thought to our interested brethren. In this, we seem to have failed. Luckily, Olsen’s Airpower Reborn is a great step toward reinvigorating and improving the critically important field of airpower theory.

For a more in-depth review of Airpower Reborn, click here.

JP “Spear” Mintz is an airpower strategist currently working on the Air Staff. The views expressed in this article are the author's and do not imply or reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the DoD, or the U.S. government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

The Cain and Abel Moment for Military Aviation: Inside History's OODA Loop

We do not know on what day or on what battlefield the first two men engaged in mortal combat. Nor do we know the first time that two ships came abreast of one another and lashed together their crews fought to the death. We do know the first time that man expanded the realm of combat into the skies.

Does knowing this change anything? How is capturing an initial moment different than only knowing of its effects and outcomes thousands of years later? Is knowing the shape of a thing at birth critical to understanding its applications later on? These were the questions I found myself asking after reading Gavin Mortimer’s The First Eagles last month.

To say that things were changing rapidly would be a terrible injustice.

Mortimer chronicles the story of a cohort of restless American innovators who apply a bit of disruptive thinking, denounce their citizenship and join the fledgling Royal Flying Corps. The newness of the offensive application of force in the physical space now known as the “air domain” is self-evident on every page. Reading this book was literally like watching a child learn to ride a bike without any instruction or guidance save that of his equally inexperienced friends. The recency of the innovation of flight and the pace of change is staggering. Just a few years after the first controlled flight at Kitty Hawk, pilots were dueling at over ten thousand feet. This leap forward is coupled with photographs of soldiers mounted on horses inspecting downed German fighter planes. To say that things were changing rapidly would be a terrible injustice.

Is it fair to look back from the passing of just a hundred years and critique ourselves for having not learned from these mistakes?

“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it,” is a familiar maxim. It is also devoid of the context of time. What is history? How long does an event take to be considered historical? In The First Eagles readers are exposed to the initial experimentations with military aviation by those who would become leading practitioners a few years later. The mistakes made are multitude and familiar yet these events can be observed without judgment. After all, no aviator in the First World War was repeating a mistake previously made. They were operating in a domain that was ahistorical. Is it fair to look back from the passing of just a hundred years and critique ourselves for having not learned from these mistakes?

As I read through the book there were events with a familiar refrain to them, as if I had seen or heard of them before.

When the Germans dispersed their superior attack aircraft across different units instead of building a cohesive, lethal organization they committed what is now known to be a fundamental mistake. The allies were able to overcome the German technical overmatch through improved tactics, returning balance and then regaining superiority in the air. The US Army Air Corps would face similar challenges with the dispersion of strategic assets at the tactical level in the early days of the Second World War. One could argue that the US Air Force, still struggling to determine exactly what its role in future conflict will be, is facing a technical overmatch — tactics problem of epic proportions today.

When some of the first American aviators serving with the British were recalled to serve as instructors in the developing Aviation Section of the US Army Signal Corps, they were not welcomed for their experience and knowledge. Rather their status as innovators and disruptive thinkers — men who acted before their institutions were ready — caused them great pain. They were belittled, disrespected and treated with a callous indifference that smacked of both envy for what they had accomplished and an institutional rigidity that left little doubt about the pace of change. It seems that talent management is a long-standing problem in the American military.

Innovations are in their purest form when first crafted. They are bare, organic, utilitarian versions of what they will become. In an effort to break the stagnant environment of trench warfare the idea of a multi-role aircraft emerged. On August 8th, 1918, the opening day of the Allied “Hundred Days Offensive,” aircraft designed for aerial combat were retasked to conduct bombing missions and other close air support activities. The results were nearly catastrophic for allied aviation. The bridges and other infrastructure targeted were too sturdy for the twenty-five pound “Cooper bombs” carried by the light aircraft and the low altitudes required to engage the targets subjected thin-skinned planes to withering ground and anti-aircraft fire. Nearly twenty-five percent of all aircraft that flew low-level missions that day were lost or rendered unflyable. The next day, the allies reassigned fighter aircraft to escort duty and left the bridge busting to the bomber squadrons. This lesson was literally learned in a day and yet, nearly a hundred years later, we still struggle with the compelling need to do less with more and strive to fill every niche in the air domain with a multirole aircraft.

These are just three lessons that were eerily familiar to me as I read through The First Eagles. There have certainly been advancements in the air domain that were built on capabilities developed in these first, pre-historical days of modern aviation. Parachutes are introduced, training protocols developed, maintenance schedules refined and improved as well as the obvious emergence of aerial tactics and strategy. With that said, the book left me asking more question of my own service and our ability to change than it answered about our history.

Is a hundred years enough time to have learned from our mistakes? Is a hundred years enough time for us to observe our Cain and Abel moment, orient ourselves to the problem, decide and act; or is history operating inside our OODA Loop?

Tyrell Mayfield is a U.S. Air Force Political Affairs Strategist. He serves as an Editor for The Strategy Bridge, is a founding member of the Military Writers Guild, and is writing a book about Kabul. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.