Mie Augier and Sean F. X. Barrett

As President Eisenhower noted, the foundation of military strength is our economic strength. In a few short years, however, we will be paying interest on our debt, and it will be a bigger bill than what we pay today for defense . . . No nation in history has maintained its military power if it failed to keep its fiscal house in order.

—Gen James N. Mattis, USMC (Ret.), 2015[1]Fiscal realities dictate that we must first divest of legacy programs in order to generate the resources needed to invest in future capabilities.

—General David H. Berger, USMC[2]

Introduction

U.S. military leaders have, in recent years, expressed concern about the deleterious effects of continuing resolutions, budgetary uncertainty, and increasing national debt on balancing the tradeoffs between readiness and future force capabilities.[3] An indication of ongoing fiscal challenges is that Marine Corps General David Berger has sought to secure funding for necessary future capabilities in the U.S. Marine Corps by divesting select legacy capabilities and capacities, thus harvesting budget space.[4] A heightened sensitivity to the importance of tradeoffs between today’s important capabilities and obtaining tomorrow’s vital priorities reflects a renewed focus by national security leaders on the interrelationship between the national and global economy, resource management, and strategy.

The wicked, ill-structured, and interactively complex problems of the present and future environment necessitate a problem solving approach rooted in a holistic understanding that is liberated from conventional bureaucratic silos…

The strategically sound allocation of resources as well as their efficient, and effective, use requires a strategic framework and vision rooted in a realistic understanding of the world as it is and not as one wishes it to be. The wicked, ill-structured, and interactively complex problems of the present and future environment necessitate a problem solving approach rooted in a holistic understanding that is liberated from conventional bureaucratic silos that breaks problems down and analyzes them as isolated, individual component parts. Resource or requirements analysis uninformed by a sound strategic vision or oblivious to the competitive and cultural context are as likely to develop the perfect solution to the wrong problem as they are to achieve an acceptable outcome.

The Roots and Limitations of Systems Analysis

The contemporary approach to linking resources and strategy rose to prominence during the early Cold War years, although applying economic analysis to national security problems dates to at least Adam Smith. A passage in The Wealth of Nations concerns the allocation of resources between “defense” and “opulence.”[5] Charlie Hitch, a pioneer of this approach, was an economist who understood that complex problems like those in national security cannot be adequately understood within the confines of just one discipline like economics. Hitch co-authored The Economics of Defense in the Nuclear Age with Roland McKean in 1960 which illuminated the importance of concurrently and deliberately addressing the interrelationship between requirements and the defense budget, resource management and assessments, and the institutional arrangements that promote efficiencies in every aspect.[6]

Until McNamara’s tenure as Defense Secretary, financial management and military planning had been largely independent of one another.

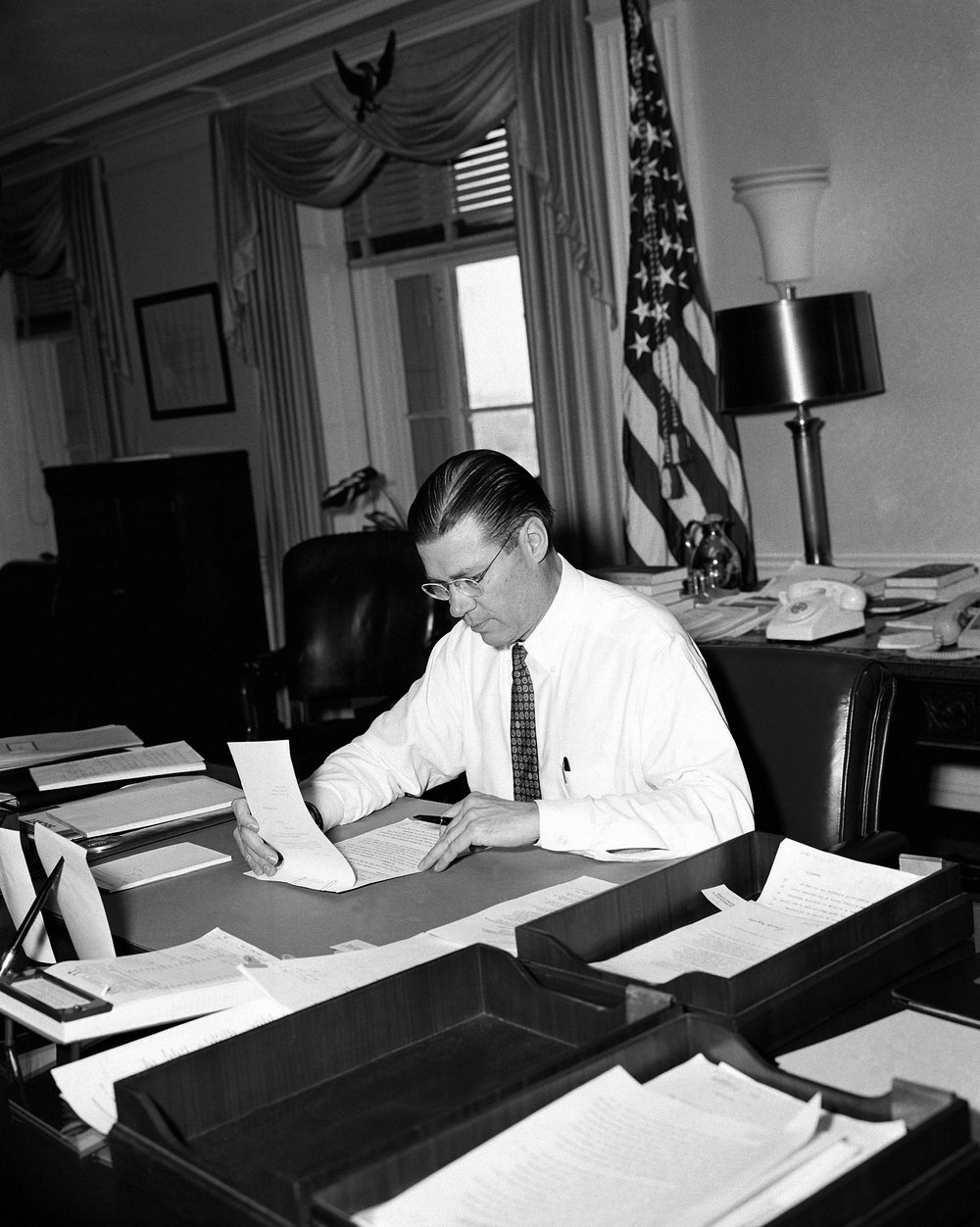

Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara works at his desk in the Pentagon on March 17, 1961. (DVIDS)

President John F. Kennedy nominated Robert McNamara to be his Secretary of Defense not long after The Economics of Defense was published. McNamara, eager to avoid being led by parochial service chiefs, found the book’s approach to managing defense equities and resources supportive of his goals. He recruited Hitch to become his Assistant Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)—a position Hitch held from 1961 to 1965. Kennedy’s Defense Secretary also implemented the administrative system and analytical approaches that Hitch and McKean had prescribed in their book. McNamara’s adoption of the book and trust in Hitch were both central to the creation of the Planning-Programming-Budgeting System (PPBS) and the systems analysis activities on which it relied.[7]

The basic premise of the PPBS was “to build a bridge between financial management and military planning to facilitate the application of operations research or systems analysis to military problems.”[8] Until McNamara’s tenure as Defense Secretary, financial management and military planning had been largely independent of one another. Planning had focused strictly on force structure and major weapons systems over a five-to-ten-year period, and budgeting had focused narrowly on functional categories like military personnel and operations and maintenance projected over just one year.

Economics or systems analysis is certainly not strategy as such, but rather a way of thinking concerned with allocating resources…

Each year, the Joint Chiefs produced a Joint Strategic Operations Plan that effectively consisted of a wish list of the services—the product of each service’s largely unilateral planning and divorced from any budget reality. Cost considerations were disregarded until after requirements had already been established. Military planners developed plans without first making reasonable assumptions as to resource constraints and, by doing so, abdicated responsibility from critical strategic choices. Relying on Hitch’s expertise, McNamara intended to upend this process and implement a recursive program where planning was informed by fiscal constraints and where budgets responded to plans instead of leading them.[9]

Economics or systems analysis is certainly not strategy as such, but rather a way of thinking concerned with allocating resources—choosing operating concepts, equipment, policies, and so on—so as to get the most out of the finite resources available and thus inform the development and implementation of a national security strategy.[10] Hitch identifies several equities relevant to strategy that benefit from economic analysis, including the impact of a country’s economic health on the purchasing power of military budgets and vice versa, how best to manage the allocation of resources to address national security concerns, as well as burden sharing and specialization in military alliances. Moreover, economics can itself be an instrument of conflict, such as trade denial and boycotts against adversaries and competing for the support of uncommitted parties and the continued support of allies.[11]

However, even as systems analysis became a standard tool for research, education, and the application of economic ideas to national security, its modern manifestations have strayed from Hitch’s vision. Recent use of systems analysis has too often resurrected the narrow parochial approach Hitch sought to displace, or simply slipped into a functionally limited form of military cost-benefit analysis.

Hitch warned against the hazards of narrow economic ideas like optimization, noting that “[t]here has been altogether too much obsession with optimizing.”[12] He cautioned that “[m]ost of our relations are so unpredictable that we do well to get the right sign and order of magnitude of first differentials. In most of our attempted optimizations we are kidding our customers or ourselves or both.”[13] Hitch observed that systems analysis should be based on observations of the real world but that it tends to fall victim to a variety of analytic pitfalls, succumbing to the draw of theoretical models to the exclusion of empirical evidence and to the application of models to problems for which they are ill-suited.[14]

While economic thinking is important to national security issues, it is equally important to recognize that economics, including thinking about and analyzing resources and requirements, is not sufficient as a lens to think through strategic issues…

The institutional success of systems analysis created new barriers within organizations even after it had broken down others. For example, the Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) and the programming and acquisitions process are notoriously lacking in agility and are only fit for doing analysis within very narrow models. For institutional and strategic leaders, the limitations and pitfalls of systems analysis as it has been institutionalized are a real barrier for developing and realizing their vision.[15]

While economic thinking is important to national security issues, it is equally important to recognize that economics, including thinking about and analyzing resources and requirements, is not sufficient as a lens to think through strategic issues and can, in fact, become its own silo and quite detrimental to strategic thinking and practice. As another renowned economist, public servant, and former Secretary of Defense, James R. Schlesinger, cautions, “Analysis is a useful tool, but it is only a tool.”[16] Resources obviously matter for strategy, but narrow disciplinary lenses like defense economics are not useful insofar as they tend toward intellectual homophily and artificially limit one’s ability to identify and think about the trends shaping the competitive environment.[17] Most central issues in strategy, competition, and conflict are the result of complex interactions between many issues, players, and the strategic environment. Economics and systems analysis can help understand parts of this, but they should not be the only—or even, the main—lens through which to try to achieve this level of understanding.

Strategy, Multi-Disciplinarity, and Problem-Centric Thinking

Andrew Marshall suggests viewing strategy as a “process of identifying, creating, and exploiting asymmetric advantages that can be used to achieve or improve sustainable competitive advantages.”[18] Thinking strategically, thus, also entails identifying and thinking through one’s relative strengths and weaknesses vis-à-vis an intelligent adversary and trying to understand how they think and might view you.[19] Economic analysis is useful for identifying these strengths and weaknesses and understanding how economic strength is related to the factors that could determine the outcomes of potential conflicts. However, its utility depends on choosing the appropriate criterion for making such determinations, thus underscoring the need first to ask the appropriate strategic questions and arrive at an accurate diagnosis of the competitive and cultural landscape, one’s place in it, and one’s ability to compete in a given area.[20]

The industrial era featured well structured, familiar, and repetitive problems for which the application of tools, such as systems analysis, to analytic problems was largely sufficient. In contrast, the post-industrial era features complex, wicked, and emergent problems that necessitate problem framing, flexibility, teamwork, and multi-disciplinary problem solving that is responsive to real world problems because today, solutions and innovations tend to lie or emerge in the interfaces between functions, offices, or organizations.[21] The essence of Hitch’s vision was to facilitate the productive mixing of people and ideas to ask the right questions, uncover erroneous assumptions, and arrive at creative solutions to wicked problems. Hitch exhorted system analysts to see their work within the context of a multi-disciplinary approach: “Systems analysis should be looked upon as a framework that permits the judgment of experts in numerous sub-fields to be combined, to yield results which transcend any individual.”[22] While economics and resource analysis are important, we must remain mindful to think strategically, critically, and holistically about how we use them.

Dr. Mie Augier is a Professor in the Graduate School of Defense Management, and Defense Analysis Department, at NPS. She is a founding member of the Naval Warfare Studies Institute (NWSI) and is interested in strategy, organizations, leadership, innovation, and how to educate strategic thinkers and learning leaders.

Dr. Sean F. X. Barrett, is an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. He has previously deployed in support of Operations IRAQI FREEDOM, ENDURING FREEDOM, ENDURING FREEDOM-PHILIPPINES, and INHERENT RESOLVE.

The views expressed are the authors’ alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

The Strategy Bridge is read, respected, and referenced across the worldwide national security community—in conversation, education, and professional and academic discourse.

Thank you for being a part of The Strategy Bridge community. Together, we can #BuildTheBridge.

Header Image: Federal Debt Held by the Public, 1900 to 2050, September 2020 (Congressional Budget Office).

Notes:

[1] Global Challenges, U.S. National Security Strategy, and Defense Organization, 114th Cong., 1st sess. (2015) (statement of General James N. Mattis, USMC (Ret.), former Commander, U.S. Central Command).

[2] David H. Berger, Force Design 2030: Annual Update (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps, 2021), 5.

[3] See, for example, Charles Q. Brown and David H. Berger, “Redefine Readiness Or Lose,” War on the Rocks, March 15, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/03/redefine-readiness-or-lose/. Generals Brown and Berger refer to this tradeoff as one between “availability” and “capability.” Separately, expressing frustration with operating under a continuing resolution, General Berger said, “[T]here’s 15 problems with that.” David H. Berger and Ryan Evans, “Gen. David H. Berger on the Marine Corps of the Future,” War on the Rocks, January 4, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/01/general-berger-on-the-marine-corps-of-the-future/.

[4] Mallory Shelbourne, “Berger Reaffirms Commitment to Force Design 2030 Overhaul In Memo to New SECDEF,” USNI News, March 1, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/03/01/berger-reaffirms-commitment-to-force-design-2030-overhaul-in-memo-to-new-secde; Berger, Force Design 2030.

[5] Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (New York: Modern Library, 1937), 431.

[6] Charles J. Hitch and Roland N. McKean, The Economics of Defense in the Nuclear Age, R-346 (Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation, 1960).

[7] Charles J. Hitch, “Management Problems of Large Organizations,” Operations Research 44, no. 2 (Mar. – Apr. 1996): 257-58.

[8] Charles J. Hitch, “The New Approach to Management in the U.S. Defense Department,” Management Science 9, no. 1 (Oct. 1962): 1. Alain Enthoven worked for and with Hitch in the comptroller’s office and at RAND and also became an important contributor to the perspective.

[9] Hitch, “New Approach,” 1-4; Hitch, “Management Problems,” 258-259; Charles J. Hitch, “Economics and Operations Research,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 40, no. 3 (Aug. 1958): 200-201.

[10] Hitch and McKean, Economics of Defense, v.

[11] Charles J. Hitch, “National Security Policy As a Field for Economics Research,” World Politics 12, no. 3 (Apr. 1960): 434-52.

[12] Charles J. Hitch, “Uncertainties in Operations Research,” Operations Research 8, no. 4 (Jul. – Aug. 1960): 444.

[13] Charles J. Hitch, “Uncertainties in Operations Research,” Operations Research 8, no. 4 (Jul. – Aug. 1960): 444.

[14] Charles J. Hitch and Roland N. McKean, “What Can Managerial Economics Contribute to Economic Theory?” The American Economic Review 51, no. 2 (May 1961): 148; Herman Kahn and Irwin Mann, Ten Common Pitfalls, RM-1937 (Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation, 1957). Hitch also warns against a narrow focus on optimization that ignores the possibility of intelligent opposition. Charles J. Hitch, “An Appreciation of Systems Analysis,” Journal of Operations Research Society of America 3, no. 4 (Nov. 1955): 466-481.

[15] The 1980s Maritime Strategy has received a lot of attention recently as an example of sound strategic thinking and design, but Secretary John Lehman oftentimes faced opposition from the Office of Program Analysis and Evaluation (PA&E, an earlier name for CAPE) to his Maritime Strategy, as analysis and efficiencies threatened to block its implementation. Dov S. Zakheim, “Lehman’s Maritime Triumph,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 4 (Autumn 2018): 141-46.

[16] James R. Schlesinger, “Use and Abuses of Analysis,” Survival 10, no. 10 (1968): 336.

[17] Herman Kahn, for example, describes “educated incapacity” as “an acquired or learned inability to understand or even perceive a problem, much less a solution.” According to Kahn, “The more expert—or at least the more educated—a person is, the less likely that person is to see a solution when it is not within the framework in which he or she was taught to think.” The Essential Herman Kahn: In Defense of Thinking, ed. Paul Dragos Aligica and Kenneth R. Weinstein (New York: Lexington Books, 2009), 238.

[18] Mie Augier and Andrew W. Marshall, “The Fog of Strategy: Some Organizational Perspectives on Strategy and the Strategic Management Challenges in the Changing Competitive Environment,” Comparative Strategy 36, no. 4 (2017): 275.

[19] Thinking about relative strengths and weaknesses and how to create and leverage strategic asymmetries also necessitates acknowledging a distinction between competition, which is an ever-present reality, and war. The importance of relative strengths and weaknesses and understanding the opponent are central to business strategy, but this is not always the case concerning the national security community’s way of thinking. Mie Augier and Andrew W. Marshall, “The Fog of Strategy,” Comparative Strategy 36, no. 4 (2017): 275-92.

[20] Hitch emphasizes that asking the right questions and choosing the appropriate criterion or criteria is crucial to economic and systems analysis. Hitch, “Management Problems,” 260; Hitch, “Appreciation,” 473-75; Hitch and McKean, Economics of Defense, viii; Hitch, “Economics and Operations Research,” 203-206.

[21] Tiziana Casciaro, Amy C. Edmondson, and Sujin Jang, “Cross-Silo Leadership: How to Create More Value by Connecting Experts from Inside and Outside the Organization,” Harvard Business Review (May-June 2019): 132. For more on the characteristics that distinguish the industrial era and post-industrial era and their implications, see Mie Augier and Sean F. X. Barrett, “Leadership for Seapower: Intellectual Competitive Advantage in the Cognitive/Judgment Era,” Marine Corps Gazette 103, no. 12 (Dec. 2019): 54-59; Mie Augier and Sean F. X. Barrett, “Learning for Seapower: Cognitive Skills for the Post-Industrial Era,” Marine Corps Gazette 104, no. 11 (Nov. 2020): 25-31. This paradigm shift has featured prominently in recent strategic documents including the Department of the Navy’s Education for Seapower study and Joint Chiefs of Staff’s guidance for professional military education and talent management. Department of the Navy, Education for Seapower (Washington, DC: December 2018); Joint Chiefs of Staff, Developing Today’s Joint Officers for Tomorrow’s Ways of War: The Joint Chiefs of Staff Vision and Guidance for Professional Military Education & Talent Management (Washington, DC: 2020).

[22] Hitch, “Appreciation,” 476-481; Hitch also notes that systems analysis is superior to, in contrast, narrowly focused intuition.