“We do not follow Maps to Buried Treasure, and X never, ever marks the spot.”

—Indiana Jones, The Last Crusade

Recently, retired U.S. Army General Ben Hodges, who formerly commanded U.S. Army Europe, lamented that most NATO maps have the Black Sea positioned on their Eastern edge, which diminishes its importance to Europe. But he noted that the simple act of centering the map on the Black Sea reveals its true importance.[1] The Black Sea is the juncture of Europe, the Caucus, Asia, and the Middle East, thus making it a critical area. World maps in Chinese classrooms, similarly, often center on China, which puts the Eastern United States and Europe at the respective edges, diminishing them in importance.[2] Every map is an argument about what is important and what is not. Today’s military strategists and leaders need to recognize maps as far more than tools for planning and navigation. Because they literally frame our thinking, maps can be a medium of conflict and a constraint on creative thinking, making map literacy a critical skill for military strategists that cannot be overlooked.

Like many officers, my first serious introduction occurred in a class at Officer Candidate School called “Land Navigation II.” After learning how to use a lensatic compass, we learned how to read a military topographic map. A topographic map, used in conjunction with a protractor and a compass, remains one of the most basic tools of the military profession. Student handouts explain that maps are a “mathematically determined representation of a portion of the Earth’s surface systematically plotted to scale upon a plane surface.” This definition is similar to the joint definition of topographic map in the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. These definitions strive to emphasize the objectivity of the map and its basis in science and mathematics. Likewise, militaries have a long history of ensuring certain areas are not depicted accurately or in detail on publicly available maps for security reasons.

By their very nature, maps are distortions of reality.

But maps are never neutral, and it is imperative that military leaders and strategists understand how they can shape and inform perspectives be employed as arguments and weapons of information and disinformation, whether they depict the 9-Dash Line or the political status of Western Sahara or the Crimea. Most importantly, strategists must recognize that every map is an argument or even a controlled fiction.[3,4] By their very nature, maps are distortions of reality. They necessarily shrink large areas to fit on sheets of paper or a screen. In this process of shrinkage, the cartographer has to prioritize information. Academics call these omissions silences—some intentional, others accidental. These omissions are usually accepted without question, as maps do not come with labels that alert the reader to the information the cartographer omitted. Denis Wood, a pioneer among modern critiques of cartography, has argued:

In our own Western Culture, at least since the Enlightenment, cartography has been defined as a factual science. The premise is that a map should offer a transparent window on the world.[5]

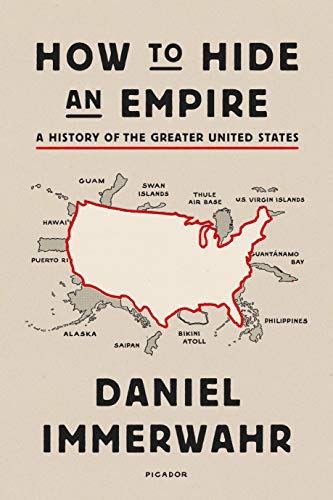

Indeed, the very “extent to which maps seem ‘real’ as well as scientific indicates the success of their performance on our collective imagination.”[6] Leaders and strategists, however, need to carefully consider what information is left off of a map. For example, many urban slums are not mapped to the same degree as other urban areas.[7] Maps of the United States rarely depict overseas territories such as Puerto Rico or Guam, marginalizing those communities in what Daniel Immerwahr has called a “a strategically cropped family photo” in How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.[8] By choosing what information to include and what information to omit, every cartographer is making an implicit argument at the least about what is important and what is not. These arguments are rarely questioned.

Maps are the prisms through which we see geopolitical realities. The scholar J.B. Hartley argues, “Maps do not simply reduce a topographical reality, they also interpret it.”[9] Hartley cautions that, even with the imagery-generated maps of today, we must “remain alert to the deviant ways in which individual technicians may have inscribed their routine tasks.”[10] He reminds strategists that “map makers are human” after all.[11] For example, it can be surprising to learn that flying over the North Pole offers the fastest route to attack the Soviet Union from the United States.[12] This is self-evident on a globe, but it may be a surprising calculation if one is working with maps. Our collective understanding of the spatial reality of the Polar Regions is also one of the most distorted on commonly-used maps.

This problem occurs in almost every area, though. The Earth is roughly spherical in shape, yet most maps are flat rectangles or squares. Representations of the Earth on a flat surface are inherently distorted. Many school children learn about the commonly-used Mercator Projection that makes Europe appear larger than it actually is relative to Africa. It can also make Greenland appear as large as South America—which it is not.

But there are also other distortions and subtle arguments that frame our understanding of geography. Most world maps in the United States put Europe and the Atlantic Ocean at or near the center. This is convenient for cartographers, because then the edges of the map fall in the middle of the Pacific Ocean where there is far less to depict. A more cynical interpretation is that putting the Western World at the center of world maps is a symptom of the omphalos syndrome where societies place themselves at the center of the world.[21] In contrast, the famous MacArthur Map puts Australia at the center of the map, and significantly changes the appearance of the world with a simple reorientation.

Maps are often political arguments, and strategists need to read them as such. Morocco, for example, has used maps to dispute its border with Algeria and effectively annex Western Sahara.[13] Guatemala does not recognize its border with Belize.[14] Argentina still claims the Falkland Islands, or Islas Malvinas, as they are called on Argentine maps.[15] Using the wrong maps can not only have planning implications but also political ones. In one episode of West Wing, President Bartlet nearly hangs a 1709 map of Palestine outside the Oval Office, but his staff convinces him otherwise, repeatedly noting that it could be seen as inflammatory because it does not depict the state of Israel. Maps have also been used to oppress and control. Hartley reminds us that as “much as guns and warships, maps have been weapons of imperialism…Maps were used to legitimize the reality of conquest and empire.”[16]

Every map is an argument about what is important, promoting a specific point of view that the cartographer embeds in the map intentionally or unintentionally.

The importance of map literacy is increasing as arguments embedded in maps are becoming ever more complex and maps are increasingly easy to create and manipulate. Scholars have identified a new type of map—known as deep maps—that use technology to frame increasingly complex narratives.[17] Recently there also have been a host of deceptive maps related to current events like depicting the spread of the novel coronavirus, which further reinforce the need for map literacy.[18] Other maps show overlapping South China Sea claims and the contested border between China and India. The Chinese government uses a historical map as the basis for its so-called Nine Dash Line claim in the South China Sea, and maps printed on Chinese passports include the claim, with countries with competing claims sometimes refusing to stamp them in protest.[19]

Maps frame our understanding of geography even though they often distort it. In The Revenge of Geography, Robert Kaplan argues people have to be careful when they use maps because they can create and reinforce biases:

Maps don’t always tell the truth. They are often as subjective as any fragment of prose… Maps, in other words, can be dangerous tools. And yet they are crucial to any understanding of world politics.[20]

Military leaders, especially strategists, need a strong understanding of both the maps that they use and their limitations. This understanding can help strategists formulate a better strategy to combat the strategies of adversaries. Maps are far more than simple tools for navigation. Every map is an argument about what is important, promoting a specific point of view that the cartographer embeds in the map intentionally or unintentionally. Maps will continue to be a political medium for promoting specific views as well as tools for understanding, with the proliferation of digital maps only making it easier to use maps to manipulate and deceive. We need to constantly ask ourselves if our understanding of a particular situation is limited by the way we are looking at it.

Walker D. Mills is a Marine Corps officer. He is an exchange instructor at the Colombian naval academy in Cartagena, Colombia. These views do not represent the opinions of the Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Sir John Murray's map of the Indian Ocean, Chart 1C, accompanying the Summary of Results of the Challenger Expedition, 1895. (Photo by NOAA on Unsplash)

Notes:

[1] Jared Samuelson, “Narrow Seas: The Black Sea with Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges,” podcast interview, (May 31, 2020) http://cimsec.org/sea-control-180-narrow-seas-the-black-sea-with-lt-gen-ben-hodges-ret/44025.

[2] Tao Tao Holmes, “China’s Classroom Maps Put the Middle Kingdom at the Center of the World,” Atlas Obscura (October 12, 2015) https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-map-youll-see-in-chinese-classrooms.

[3] J.B. Harley, The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 57.

[4] Denis Wood, Rethinking The Power of Maps, (New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2010), 43.

[5] J. B. Harley, “Texts and Contexts in the Interpretation of Early Maps,” in From Sea Charts to Satellite Images: Interpreting North American History through Maps, ed. David Buisseret (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 3–4.

[6] Rob Sullivan, Geography Speaks: Performative Aspects of Geography, (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011), 84).

[7] Gregory Warner, “In Kenya, Using Tech To Put An 'Invisible' Slum On The Map,” NPR Morning Edition, (July 17, 2013). https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2013/07/17/202656235/in-kenya-using-tech-to-put-an-invisible-slum-on-the-map.

[8] Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), 13.

[9] Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 45.

[10] Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 41.

[11] Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 41.

[12] John T. Corell, “Intercepting the Bear,” Air Force Magazine (February 26, 2018) https://www.airforcemag.com/article/intercepting-the-bear/.

[13] Stephen Zunes and Jacob Mundy, Western Sahara: War, Nationalism and Conflict Irresolution, (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2010), 36-38.

[14] Scott Neuman, “All Over the Map: Cartography and Conflict,” NPR (November 28, 2012) https://www.npr.org/2012/11/28/166079782/all-over-the-map-cartography-and-conflict.

[15] Neuman, “All Over the Map.”

[16] Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 57.

[17] Worthy Martin, “Warp and Weft on the Loom of Lat/Long,” chapter in Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2015) 203-222.

[18] Jordan Branch, “Be careful what you’re learning from those coronavirus maps,” The Washington Post, (March 11, 2020). https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/11/be-careful-what-youre-learning-those-coronavirus-maps/.

[19] Phillip Heijmans, “Philippines Will Start Stamping Chinese Passports for First Time in7 Years, Bloomberg, (November 6, 2019) https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-11-07/philippines-to-stamp-chinese-passports-with-nine-dash-line.

[20] Robert Kaplan, The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate, (New York, NY: Random House: 2013) 27.

[21] Samuel Edgerton, “From Mental Matrix to Mappamundi to Christian Empire: the Heritage of Ptolomaic Cartography in the Renaissance,” chapter in Art and Cartography, (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1987) 26.