Good strategy explains why we do what we do. It ties together a nation’s political objectives with the resources at hand; it gives purpose to the tactical actor. Bad strategy muddles these things into a slurry that lacks sufficient consistency to be of use to anyone. The pieces can’t be seen for the whole. Adding more ingredients and blending more doesn’t make it better, neither does renaming it.

Redefining the objective once you’ve begun suggests you were never ready to begin in the first place.

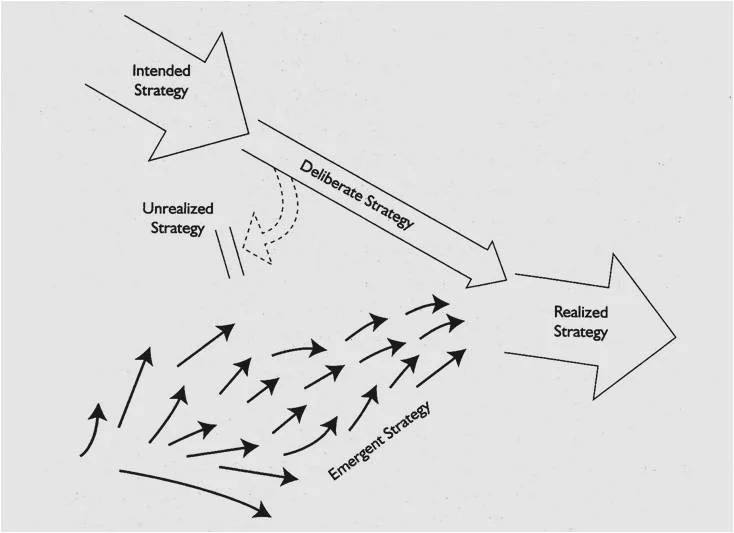

This is to say that once a nation identifies a desired objective, and crafts a coherent, comprehensive strategy, it should then pursue it across all domains of national power. If the objective changes, it’s not because you have a bad strategy; it’s because you probably didn’t look far enough down the road and decided to move the goalpost. Redefining the objective once you’ve begun suggests you were never ready to begin in the first place. Strategies take time to develop and years to execute — they are never truly completed. The position of advantage which a strategy envisions achieving should be properly considered. Changing your strategy after you’ve begun movement is like trying to recall a bottle rocket.

With this said it is important to recognize that strategies can only be evaluated against other strategies within the given context, not against some ideal. A strategy to achieve the unachievable isn’t a strategy; it’s a dream, and a strategy to reach an ambiguous political objective is a path so broad that one might wander lost in the desert for decades.

This is to say that without a clear and precise picture of what you want achieved, it might be best to delay developing a strategy. Carl Builder writes that “In real strategies, the means and ends are usually quite obvious and so sometimes (not surprisingly) are the underlying motives.”[1] If the means and ends are obvious and known, this puts them in the realm of the science of strategy, the art therefor, lies in the way — the “who” and the “why.” But this is an oversimplification of the challenge of strategy, for it is not created in a vacuum. Strategy is informed, limited, exposed and curtailed by policy, politics, capabilities and our will to act.

This is where America stumbles. Formulating strategy in pluralistic, open, democratic societies is difficult.[2] It’s difficult because as a nation, America is not a static thing; it is, rather, a thing in a constant state of evolution. It’s hard to know what you want, when you don’t quite know who you are or who you’ll be tomorrow.

A solid strategy should unite all the instruments of national power into a single purpose — to achieve the ends identified by the nation’s political leaders.

A solid strategy should unite all the instruments of national power into a single purpose — to achieve the ends identified by the nation’s political leaders. In doing so, it forces the instruments of national power — manifested in the institutions of diplomacy, information, military and economics — into outward action and reduces their capacity for internal reflection and development. In short, strong strategy properly implemented freezes the conversation about the identity of these intuitions and the nation and insists on their unified action.

Strategy helps define who we are. In the absence of implicit, compelling strategy, we seek to define ourselves. A cursory look at contemporary American history helps develop this pattern (though this is clearly not comprehensive).

Throughout the 1800s, America was moving in two directions — industrialization and agricultural expansion — which drew on two dramatically different societal constructs. This tension culminated in the Civil War and a strategy of unification for the Union.

America continued to grow through mass immigration and geographical expansion in the decades that followed. The First World War forced America to look abroad for the first time, and begin to develop its identity as an emergent hegemon with a strategy for re-establishing order in Europe.

The period between the World Wars was one of rampant social change: women’s suffrage (1920) and prohibition (1920–33); the great depression (1929–1939) and culminated in America’s return to the global scene with the Second World War and a “Europe First” strategy followed by a “Pacific Pivot.”

Postwar America was again rife with cultural changes. The sexual revolution, racial tensions and other liberal movements paralleled two inconclusive wars in Korea and Vietnam. This suggests the strategy of containment had limitations which resulted in stalemated wars. Perhaps the threat of communist expansionism was not — as much as we wanted it to be — existential.

The bi-polar world turned cold. America and the Soviet Union stared at each other, their identities firmly rooted in the other. And then the Soviets left us. A unipolar world wobbled, rebalanced, and then the peripheries began to unravel.

It seems that threats emerge faster than America can develop strategies to meet them.

Cartoon courtesy of Wiley Ink, inc. “Non Sequitur”

Having fought two inconclusive wars, perhaps it is in this same period of flux which came after Vietnam that America finds itself again. Except now America has no “other” to stare at and so it finds itself gazing into a mirror as it wanders the periphery, dabbling, never decisively engaging; pulsing, probing, prolonging. The absence of an existential threat, a recovering economy and dramatic social tensions has America looking inward at the problems at the threshold of its own domesticity while it fights half-pitched holding actions in a dozen entropic countries where it thinks its next existential threat might emanate from.

Is our own identity so driven by the presence of an opponent that without one, we are lost?

America’s continued wars pose serious challenges for those who develop strategy. There seems to be a disparity in the list of desired objectives and the policy which dictates the boundaries of the lane in which strategists are allowed to maneuver. The conditions which we once sought no longer seem viable and the environment in which we find ourselves operating even more volatile. It seems that threats emerge faster than America can develop strategies to meet them. Perhaps it’s because as individual threats, they don’t warrant a strategy. It’s also possible that America is asking the wrong questions of its strategists.

For the last two hundred years, external conflict and tension have driven the development of our strategies. It has shaped our thinking and hardened a paradigm which America uses to rationalize the world. America looks for threats to build and plan against, it’s how it seem to have always been. Is our own identity so driven by the presence of an opponent that without one, we are lost?

We are not the same America we were twenty-five years ago. The world is not the same either. Perhaps the answer is to look for opportunities — not threats — and build a strategy that leverages relationships to help others manage regional troubles as they emerge.

Tyrell Mayfield is a U.S. Air Force Political Affairs Strategist. He serves as an Editor for The Strategy Bridge, is a founding member of the Military Writers Guild, and is writing a book about Kabul. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Carl H. Builder, The Masks of War: American Military Styles in Strategy and Analysis.

[2] Carl H. Builder, The Masks of War: American Military Styles in Strategy and Analysis.