Whatever the claims of certain media outlets, the organisation referred to variously as ‘Islamic State in Syria’ (ISIS) or simply ‘Islamic State’ is hardly a new phenomenon in Middle Eastern history. Islam has been beset by violent schismatic and revivalist movements before, some conquering large territories and proclaiming ‘states,’ only to implode under their own internal contradictions or be crushed militarily by more established Muslim rulers. Perhaps the starkest example of this was the very entity originating the uncompromising brand of Sunni fundamentalism espoused by al Qaeda and ISIS, the Wahhabi-Saudi emirate of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which engaged the established powers in the Middle East in just the kind of ‘generational struggle’ today’s biens pensants say will be needed to defeat ISIS, a struggle having repercussions for the region today. It lost, and many of the reasons why suggest ISIS will lose too.

The Emirate arose from the region’s political geography. Hejaz, on the west coast of Arabia and containing Islam’s two Holy Cities, was an Ottoman satrapy from 1517 to the First World War; Hasa, on the eastern coast, was Ottoman territory from 1550 to 1670, and between them was Nejd, the birthplace of Wahhabism. Wahhabism rose partially in reaction to the crumbling of Ottoman authority across the Middle East, beginning with their defeat at Vienna in 1683, after which the Empire’s main source of income, plunder, dried up and it resorted to heavy taxation to compensate. This worsened the corruption and heavy-handedness already facts of life in the Empire, and some provincial satraps took the opportunity to loosen Istanbul’s control over them, the Sharifs of Hejaz evolving from subjects to semi-independent suzerains keeping an increasing share of the profits and taxation from the Hajj for themselves, while in Hasa, the Bani Khalid tribe ejected the Ottomans in the 1670s and began raiding neighbouring provinces in pursuit of tribute and new vassals.

Antique print of a Ghazu , or Arabic traditional raid.

Nejd was poor, sparsely inhabited, and consisted mainly of small agricultural settlements grouped around oases separated by vast tracts of arid wilderness. These were helpless in the face of the growing aggression from the Bedu tribes of Hasa and Hejaz, the Hejazis raiding Nejd from the 1720s; there was no one dominant power in Nejd and tribal warfare was chronic throughout the region even without these irruptions from its neighbours. The Bedu sense of superiority and entitlement over other Arabs was reinforced by the tradition of the Ghazuor raid, a staple of their society and the very basis of warfare in central Arabia. With no order beyond the tribal, in lean years the Bedu supplemented their frugal existence by stealing livestock, slaves and other goods from their settled neighbours, trade caravans and rival Bedu tribes, a man’s status often hinging on how he performed during these raids. This was supplemented by khuwwaor ‘brotherhood tribute,’ a euphemism for protection money paid to the Beduto avert further raiding. In some cases, the scale of khuwwa drove payees into vassalage of the Bedu tribe extracting it, and ‘warfare’ in the region consisted generally of chronic Ghazu raiding lasting until one side or the other gave in and agreed to pay khuwwa. Despite, or perhaps because of its targeting by rapacious Bedu, it was from Nejd that the two political forces which were to dominate much of the history of the Arabian Peninsula over the next 300 years were to emerge: the Wahhabis and the House of Saud.

The Wahhabis are named for the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (c1703-c1795) who preached a brand of rigid, uncompromising Sunni Islam inspired by the teachings of the ninth century theologian, Ahmed ibn Hanbal, and their revival by the Hanbali jurist, Sheikh ibn Taimiyya, four hundred years later. These centred on the question of how far Islam, originally a Hejazi movement, should adapt to the cultures of others as it expanded. The most important scriptures in Islam are the Koran itself, and the Hadiths, the sayings of the Prophet, which, collected into the Sunna, lay out the correct code of behaviour for all Muslims. The Sunna must be interpreted constantly to reflect change in human society, and Islam has evolved through the recognition and adoption of new traditions once they satisfy the Ulema, the body of Koranic scholars within a community, that they conform to the Sunna. A tradition not yet approved is known as a bid’ a or man-made innovation, and there are different schools of thought within Sunnism on the status of bid’ a; Hanafism, the ‘state Islam’ of the Ottoman Empire, was tolerant of bid’ a while Ahmed ibn Hanbal and his followers rejected bid’ a altogether, claiming it consisted of unacceptable man-made variations on God’s law and contesting that the Koran and Hadiths, interpreted rigidly, literally and without nuance, were the only guides the faithful needed. To ibn Hanbal’s teachings ibn Taimiyya added a single, non-negotiable interpretation of jihad, the Muslim’s struggle for his faith, as jihad kabir, holy war, particularly against those who claimed to be Muslims but did not reject bid’ a or abide by ibn Hanbal’s rigid interpretation of Shari’ a—Shi’ites, Sufis and Ibadhis, for instance, all viewed as apostates to be either corrected by the sword or killed without mercy.

His solution was the community’s complete submission to the authority of a warrior Imam who would then lead them in Holy War against these backsliders.

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab was the son of a qadi, a religious judge of Uyaina, and spent several years studying under Hanbali theologians in Medina, after which he studied and preached in Basra, Qom and Hasa, his travels exposing him to Shi’ism and Sufism, as well as non-Hanbali Sunnism, and leading evidently to a fierce rejection of all. Upon returning to Nejd around 1730, he found many things he liked even less, particularly the cults of Islamic saints and in response began to preach a form of Sunnism rooted in strict belief in the oneness of God, and that revering anyone or anything else—even the Prophet himself — constituted bid’ a, was un-Islamic and risked backsliding into pre-Islamic paganism. His solution was the community’s complete submission to the authority of a warrior Imam who would then lead them in Holy War against these backsliders.

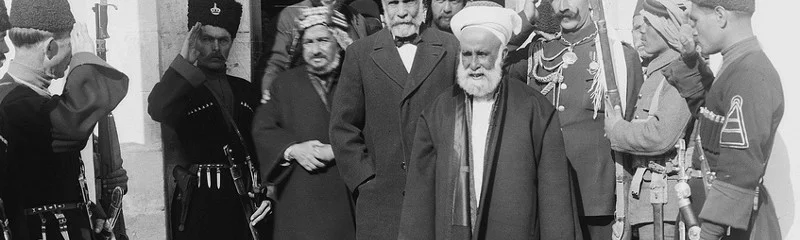

King Ibn Saud and King Faisal in 1922.

Abd al-Wahhab forged a short-lived alliance with the Emir of his home town, Uyaina, and oversaw the destruction of saints’ shrines in the area and the stoning to death of an adulterous woman, but, under pressure from the Bani Khalid, his nominal overlords, and the localUlema, the Emir of Uyaina sent Abd al-Wahhab into exile in Darriyah, where he contacted the family of the Emir there, Muhammad ibn Saud. The al Sauds were originally a Bedu clan who settled in the Darriyah region in the fifteenth century AD to become merchants and date farmers; Muhammad Ibn Saud had been head of the clan and emir of Darriyah since 1727, his wealth allowing him to defend the settlement from raids by Bedu and other oasis clans. Muhammad was ambitious and realised the political potential of a religious movement preaching war against unbelievers; the Wahhabi-Saudi alliance was cemented in 1744 by a mutual oath in which Muhammad converted to Wahhabism and recognised Abd al-Wahhab as master of the community in all religious matters and in return Muhammad had bestowed on him the status of Imam, this being reinforced by the marriage of Muhammad’s son to Abd al-Wahhab’s daughter.

The al Sauds then began turning Arabia back to the ‘true path,’ subjugating Nejd and the surrounding areas rapidly, helped by Abd al-Wahhab’s impressive knowledge of contemporary military developments, particularly firearms, and by an elite force of regular cavalry forming the ‘hard core’ of what was mainly a tribal army based on a feudal levy of all men aged eighteen to sixty. A hundred years before On War, the al Sauds demonstrated an instinctive understanding of many of the key principles attributed to Clausewitz. For them, war emphatically was an extension of tribal and religious politics with an admixture of other means, in which the aim was to compel others to do their will by putting them in a position where giving in was less painful than to go on fighting. The al Sauds did not ‘conquer’ territory per se but rather adapted the Ghazu to their political ends. Neighbouring tribes were raided mercilessly under the pretext of carrying off the property and slaves of ‘apostates’ for the benefit of the community of ‘true Muslims,’ with proceeds split 20% to Muhammad al Saud in his capacity as Imam and the rest divided among the warriors carrying out the raid (as was traditional with the Ghazu) Indeed, one of the most notable features of the Wahhabi way in warfare was the slaughter and looting which accompanied it, continuing until the ‘apostates’ saw the light, became Wahhabis, agreed to pay tribute to the head of the al Sauds in his capacity as Imam, and to provide armed men for further jihad.

This proved eminently effective in central Arabia, a region of small, scattered oasis towns incapable of resisting a large organised force. By 1773, the Saudi-Wahhabi emirate had subjugated Nejd and the whole of central Arabia by the 1780s. Muhammad ibn Saud did not live to see this, being assassinated in 1766, and Abd al-Wahhab died in 1792, but by 1800 Muhammad’s heir, Saud, had established a sizeable emirate in central and eastern Arabia rooted in strict Tawhid and Shari’ a and defying the authority of the Ottoman Sultan, the nominal Khalifa of all Sunni Muslims.

The Wahhabis began attacking northwards into Ottoman Mesopotamia, sacking the Shi’ite holy city of Karbala in 1802, massacring 4,000 men, women and children, smashing the tomb of Imam Hussein (the Prophet’s grandson and one of the most revered figures in Shi’a Islam) and Shi’ite mosques, ransacking the city and carrying off tons of goods, and the following year raiding Hejaz towards Mecca and Medina. Mecca was occupied temporarily, without a fight, in April-July 1803, and although there was no Karbala-style massacre, the Wahhabis smashed the tombs of Islamic saints and tore off the ornamentation from the Kaaba, which they viewed as defacement, force-converted the population and refused entry to any pilgrim who would not become a Wahhabi. In August 1803, the Wahhabis were expelled from Mecca by the troops of the Ottoman Pasha of Baghdad, but responded by blockading the pilgrimage routes to Mecca and Medina. Medina capitulated in summer 1805, and the Wahhabis annexed the whole of Hejaz later that year. The harassment of non-Wahhabi pilgrims became a major issue over the next six years, culminating in the refusal of entry to Mecca of official Ottoman caravans carrying the annual tribute of a richly decorated cover for the Kaaba, which the Wahhabis claimed was a ‘violation’ in what was almost certainly a symbolic act of provocation.

Yet, confronting the Emirate militarily would be problematic: the main centres of Wahhabi influence lay deep in Arabia, hundreds of miles from the Ottoman frontiers beyond natural barriers of mountains or desert. Marching the main Ottoman army from Anatolia would be prohibitively expensive and would leave other frontiers vulnerable (the Empire’s northern frontiers were under constant threat from Russia and war would break out again in 1806), and forces of the Ottoman governors of Baghdad and Kurdistan could barely contain the Wahhabi raiders as they stood. Consequently, in 1811, the Sultan delegated this task on the most powerful of his nominal vassals, Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt.

An 1840 portrait of Muhammad Ali Pasha by Auguste Couder.

Muhammad Ali Pasha was an Albanian, born in 1769, the same year as Napoleon, which he saw as an omen, as he idolised the Little Corporal and took him as a role model. In 1799 he was a major in the Ottoman Army and second in command of an Albanian regiment sent by the Sultan to form part of the army resisting Napoleon’s invasion. He was a highly ambitious man, and in 1805 led a revolt In Egypt against the Ottomans at the head of his Albanian soldiers, supported by Muslim clerics and other local worthies. Such was the Empire’s inability to do anything about it that this ended with a compromise: Major Muhammad Ali became a Pasha, the Turkish equivalent of a lord, and appointed Khedive of Egypt. A Khedive was effectively a viceroy, the de facto monarch of his territory, tied to the Sultan only by an oath of fealty which most ignored. In 1811, Muhammad Ali seized direct control of most of the agricultural land in Egypt and decreed what crops the peasants should grow, in particular tobacco, sugar, indigo and, above all, cotton, the peasants being issued by the state with seeds, tools and fertilizer. Consequently, Egypt moved from being a poor, backward subject of the Ottoman Sultan to a state mass-producing cash crop for export to Europe. Muhammad Ali used the revenues to modernise Egypt, beginning by paying for bright young Egyptians to attend universities and military academies in Europe, the first subjects of the Ottoman Empire to do so. He also paid Westerners to come to Cairo and Alexandria to found schools for doctors and engineers and brought in ex-officers from Napoleon’s army to train his army, which evolved into a European-type force with uniforms and badges of rank and formed into regiments. This army was the biggest in the Middle East and for a while, it, and its economic might, turned Egypt into the region’s superpower.

It was therefore logical for Muhammad Ali to be entrusted with crushing the Wahhabis. In March 1811, his son, Tussun Pasha, marched into Hejaz with an 8,000-man force and retook the region after an extremely costly two-year campaign. The Wahhabis used their superior knowledge of the mountainous terrain of Hejaz to wage an obdurate defence, at one point ambushing Tussun Pasha’s army in a narrow pass and inflicting heavy casualties. Nevertheless, an undeterred Muhammad Ali sent sufficient reinforcements to retake the two Holy Cities and in 1813 was able to accompany the Hajj, sending the keys of Mecca to Sultan Mahmud II to show he once again was master of the heartlands of Islam.

Realising that there was no ‘containment’ of the Wahhabi threat, only eradication, Ibrahim Pasha invaded Nejd with 8,000 men and headed straight for Darriyah, the closest the Wahhabis had to a political ‘centre of gravity.’

The Wahhabis followed the time-honoured Bedu practice of retreating into the desert in the face of superior force, fighting continuing sporadically on the Hejaz-Nejd frontiers until Tussun negotiated a truce with Abdullah Ibn Saud in 1815, which was broken upon Tussun’s death shortly thereafter. In 1817, Muhammad Ali appointed his other son, Ibrahim Pasha, to succeed his brother: a capable and aggressive commander, Ibrahim Pasha was to be his father’s ‘attack dog’ for the next two decades. Realising that there was no ‘containment’ of the Wahhabi threat, only eradication, Ibrahim Pasha invaded Nejd with 8,000 men and headed straight for Darriyah, the closest the Wahhabis had to a political ‘centre of gravity’. A terrible six-month siege ensued, the Wahhabis trapped inside the walls and starving, the Egyptian Army outside slowly running out of water in 50-degree heat. The Wahhabis cracked first, surrendering on 11 September 1818, the Egyptians entering the town and massacring the population; the head of the al Saud clan, Abdullah, was taken in chains to Cairo and then Istanbul and beheaded at the gate of the Topkapi Palace.

So what might this tell us about ISIS?

In a region where there is no clear division between spiritual and secular, religious matters will soon become political ones and potential causes of conflict. In both cases, an ungoverned vacuum, full of violent men, had inserted into it a rigid, black and white spiritual creed, easy to understand and promising paradise for life lived according to a code which not only justified war against anyone who was different but made it a spiritual obligation. Those men in turn brought their aggression and rapacity, making war with ‘unbelievers’ almost inevitable. And, like ISIS, the Wahhabis then had the luxury of expanding into that ungoverned vacuum.

At some point it will be necessary for a revolutionary movement to cease being a revolutionary movement and start to govern. The Wahhabis never reached this point, and bringing the whole Muslim world back to the ‘true Faith’ was never within their capabilities. Yes, they conquered a vast area, but apart from the Holy Cities this consisted largely of villages and oases scattered across open desert, with little communication between them, and there seems to have been little attempt to rebuild areas they had razed during their conquests. There was no ‘state’ apparatus whatsoever, no attempt to ‘govern’ the areas they had subjugated beyond the personal decisions of senior members of the al Saud clan. Again echoing ISIS, the Emirate had no external policy beyond perpetual aggression towards its neighbours, interspersed with crass provocation of outside powers. There were probably practical reasons for this: without the promise of plunder, many warriors would lose their incentive to support the Saudi-Wahhabi emirs, who from 1805 gradually opened up to trade with the ‘apostates,’ undermining their authority, which was eroded further by what was to become a common factor in Saudi history, the wide gap between the demands of Wahhabi teaching and the ruling family’s luxurious lifestyle, funded in many cases by selling plundered treasures wholesale — shades of ISIS’ black market oil trading and Omar al Baghdadi’s designer watch here. It is not hard to predict how the many criminals and religious maniacs in ISIS’ ranks would react were it to try to settle into ‘normalcy’. Moreover, the rapidity with which the Emirate collapsed indicates that it had done little or nothing to win over the local population.

A purely military solution to such groups is not only possible, but may be the only viable one. The Ottoman Empire was not renowned for seeking negotiated settlements with rebels; besides, negotiation with an entity containing large numbers of homicidal religious maniacs and bandits was unlikely. Such people only understood one language, and the Ottomans spoke it eloquently throughout their history. While the area’s geography was problematic, once military force was applied intelligently and ruthlessly, the Emirate’s many weaknesses came into play. It is likely the same will apply with ISIS.

Dr. Simon Anglim is a Teaching Fellow at King’s College London and the author of “Orde Wingate: The Unconventional Warrior.” The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.