Zachery A. Fry reimagines the camps and battlegrounds of the Army of the Potomac as focal points of ideological debate. Enlisted men not only reflected partisan divides of the broader Northern public but directly engaged in the political process through correspondence, voting, and political resolutions. This book sheds light upon mobilization within the ranks to reframe notions of political space and activity during the Civil War.

#Reviewing Union General

Shea successfully demonstrates that more attention should be paid to this understudied Union general. Curtis’ wartime emancipation policies should shift historians’ narrowed focus away from the Eastern Theater to more thoroughly integrate the trans-Mississippi West into their analyses of wartime emancipation. Hopefully, Union General will inspire other historians to incorporate Curtis into the current historiography on wartime emancipation, the Missouri and Arkansas home front, and Civil War memory. Ultimately, Union General is a worthy addition to the scholarship on military leadership and will appeal to readers.

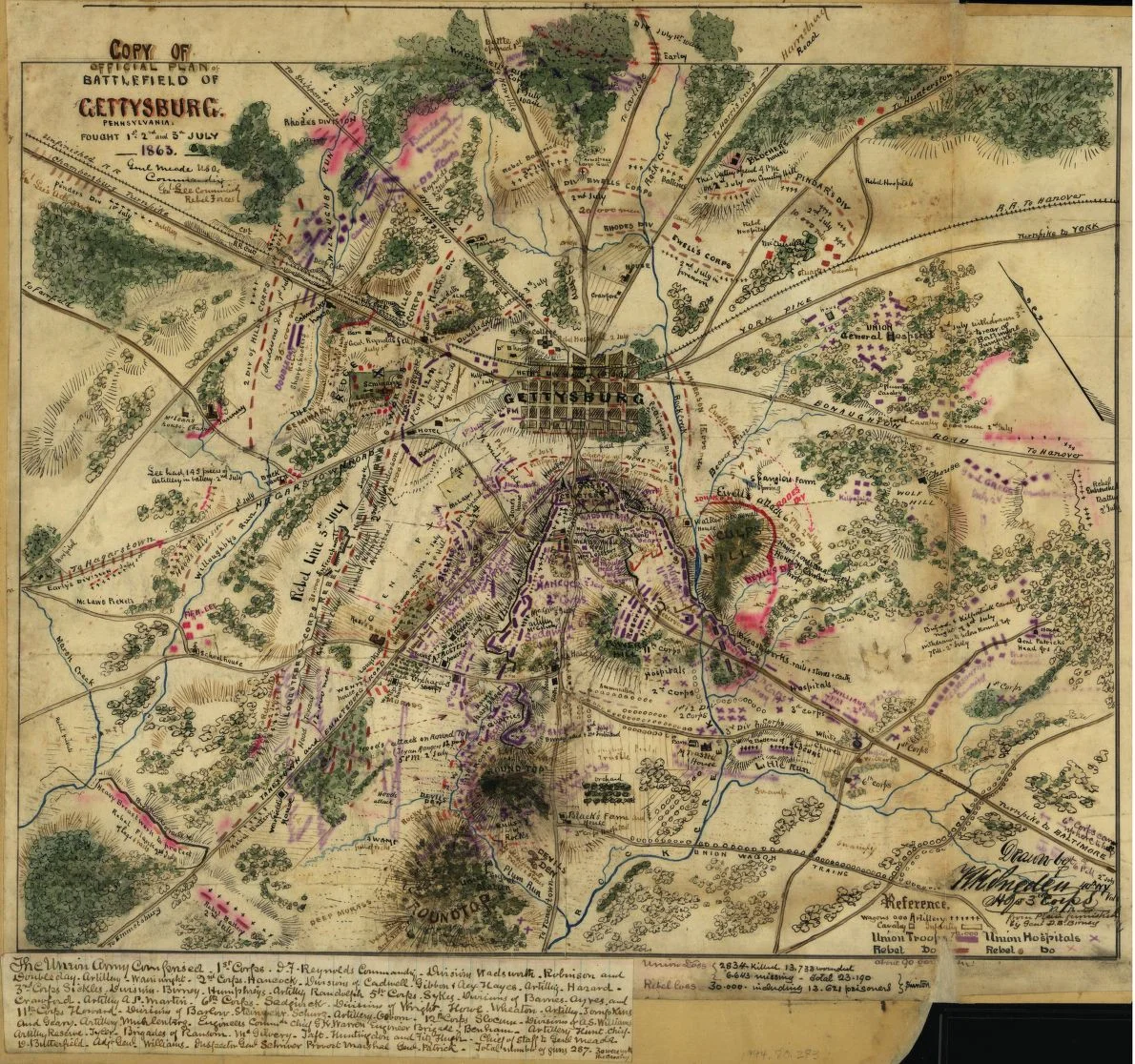

Up The Emmitsburg Road: #Reviewing Gettysburg's Peach Orchard

For generations of military historians, the Emmitsburg Road, the highway that runs from Emmitsburg in Maryland into southern Pennsylvania—and that, over the course of a single mile, bisects the Gettysburg battlefield—has served as a kind of festering gash in America’s historiographic landscape. The road’s importance is at the heart of Lee’s attack plan on the battle’s second day, when he directed Longstreet to use it as the geographic centerpiece of his assault. Longstreet, Lee said, was to attack “up the Emmitsburg Road.” The problem is that while Lee had an apparently clear vision of what he meant, at least some of his subordinates, and generations of historians, did not.

Getting Past the Civil War: The Morality of Renaming U.S. Army Bases Named After Confederate Generals

One hundred-and-fifty-five years after the end of the Civil War, as the growing movement to remove memorials and monuments to Confederacy suggest, it appears Lee was right in his opposition. Moreover, whatever one believes about Lee’s decision to fight for the Confederacy, it is well past time to take his advice.

Strategy from the Ground Level: Why the Experience of the U.S. Civil War Soldier Matters

The long-serving professionals of the modern U.S. Army may seem worlds apart from their citizen-soldier forebears. Yet, the lessons outlined here have echoes in the present. A growth in military marketing and benefits following the rise of the all-volunteer force in 1973 testifies to the ongoing effort to satisfy the motivations of prospective recruits.

How Romanticization of the U.S. Civil War Whitewashes Political Violence

Curiously, the rise of political tribalism in the 1990s, similar to the 1960s, coincided with a general rise in interest in the U.S. Civil War, America’s bloodiest and most costly political conflict. Since its conclusion in April 1865, the Civil War, cloaked in Lost Cause mythology, has inspired anti-federal government and white supremacist ideology like that of William Luther Pierce, a fierce defender of the antebellum South and the author of the dystopian racist novel The Turner Diaries, which inspired the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh. The depiction of the Civil War in print and film in the late 1980s and early 1990s appealed much more to the broader masses than it had in prior times.

Terrorism in Civil Wars

Terror tactics are used for different reasons depending on the time of the civil war. Once the war has begun, terrorism is used to stimulate it. Before or in the beginning of the civil war, terrorism is used to convince the local population of the need for a revolution by attempting to change the beliefs of the people and intentionally getting them on board with violent methods. At the end of the war, terror tactics have been used to delegitimize the peace.

The Battle of Monocacy: Reflections on Battle, Contingency, and Strategy

The Battle of Monocacy, in part because of its relative obscurity, but also because of the complexity of its strategic effect, opens up interesting questions about historical contingency, the meaning of victory and defeat, the duality and ambiguity of war and strategy, and the narratives that take hold and those which fade away.

A Man Apart: The Political Education of General William Sherman at the Battle of Shiloh

Roaring thunder and rain cascading in sheets shrouded the day’s horrific toll by drowning out the cries of the wounded and dying strewn about the ground and cloistered in hospital tents. The carnage was stunning to all involved, save for the prophet whose “gallant and able” leadership under fire prevented a catastrophe. William Sherman’s redemption was at hand.

Shiloh: Storm Cloud of Revolution

#Reviewing Lincoln’s Lieutenants

Stephen W. Sears, author of twelve prior Civil War volumes, reassesses the Eastern Theater in Lincoln’s Lieutenants: The High Command of the Army of the Potomac. It explores two topics germane to the modern military. Strategists will note that the Army of the Potomac was the most important Northern force and fought in the preeminent theater. Russell F. Weigley claims that this area “offered the most promising opportunity for a short war and thereby the limitation of costs and destructive violence.” Students of civil-military relations will focus on the relative politicization of the officer corps and whether President Abraham Lincoln could impose his strategic vision on commanders.

#Reviewing Emory Upton: Misunderstood Reformer

The heart of this biography is the account of Upton’s career as a military reformer. Here, David Fitzpatrick has succeeded. Too often we are ignorant of the origins and take for granted many aspects of military training, education, doctrine, leadership, and organization. By understanding the hard-experience that gave rise to these foundational aspects of the military profession, there is still plenty of opportunity to continue Upton’s work in improving it.

Vicksburg: The Past and Future of Amphibious Operations

The Vicksburg Campaign yields a number of lessons for tacticians and strategists. Grant was a talented commander to be sure, but the most important reason for his success was the Union Navy under the able leadership of Admiral Porter. Not just its presence, but the tight coordination between the two allowed one to support the other and vice versa. Land and sea are too intimately connected during amphibious campaigns for the typical supported/supporting relationships to work, there must be symbiosis.

The Passion of General James Longstreet

#Reviewing American Ulysses: The Rehabilitation of an American Hero

Theodore Roosevelt, a man who held the unique distinction of being both an historian and a president, once wrote of American history, “Mightiest among the mighty dead loom the three great figures of Washington, Lincoln, and Grant.” Roosevelt’s words would come as a shock to most Americans today. Although Grant’s reputation has undergone a rehabilitation in the last two decades, he hardly ranks among great American leaders in the minds of all but a handful of historians, and the popular conception of Grant as an inept drunk still lingers.

We Want It, What Is It? Unpacking Civilian Control of the Military

The nomination of James Mattis as Secretary of Defense briefly brought the often overlooked concept of civilian control of the military to public attention. Commentators debated whether Mattis’ qualifications, personality, and presumed influence on the administration justified an exception to the law prohibiting recently retired generals from serving in that post. Reassuringly, in that discussion as well as in the larger conversation about the unusual number of retired and acting general officers now serving in traditionally civilian posts, there has been no discernible challenge to the notion of civilian control of the military. Yet underneath this consensus as to the desirability of civilian control, hide differences in understanding about what it actually entails. In short, we want civilian control but do not precisely know what it is.

#Reviewing A Savage War

Over the last couple years and in various papers, I have frequently cited Clausewitz, Thucydides, and Sun-Tzu in my writing, but more as passwords into a military writing corps that constantly trots them out than as a true believer. A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War, by Williamson Murray and Wayne Wei-Sieng Hsieh, made me reconsider my opinion on these classics.

Leadership Lessons from Gettysburg

Military leadership comes in all different forms. It can be embodied in the leadership of troops on a battlefield, or it can occur behind the scenes in moments no less important. The Army defines leadership as influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to improve the organization and accomplish the mission. These bland, doctrinal terms are best brought to life in the form of historical vignettes, a valuable tool for teaching the process of leadership.

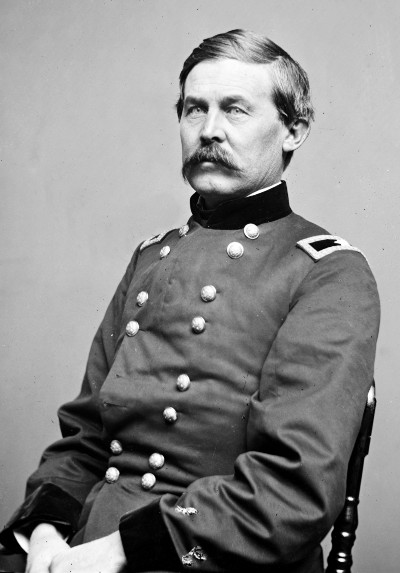

Architect of Battle: Buford at Gettysburg

Late in June 1863, the divisions of two great armies roamed Maryland and Pennsylvania. In retrospect, their confrontation at the crossroads of Gettysburg seems almost inevitable. However, the outcome of that confrontation was largely the work of one Union officer. This officer was born in Kentucky to a Democrat family. He would lead the First Division of Union Cavalry under orders to secure the crossroads in the vicinity of Gettysburg. How he executed these orders ensured the Union Army the best chance of victory in the upcoming battle.

He serves as a case-study in the theoretical and practical applications of tactics and strategy.

Buford as portrayed by Sam Elliot in the exceptionally detailed film Gettysburg.

Though General Buford is relatively well known to Civil War buffs, and has been played by Sam Elliot in the Gettysburg film, the extent of his contributions in the summer of 1863 remain more obscure. This is unfortunate. He serves as a case-study in the theoretical and practical applications of tactics and strategy. His leadership prior to the battle ensured that his troops were well prepared and ideally positioned for the Confederate advance. The leadership and defensive concepts he employed remain relevant today.

Buford’s objective on June 29th was to secure the town of Gettysburg for consolidation of the Army.

Buford studied cavalry tactics at Fort Crittenden, developing the idea of cavalry used as dismounted infantry in order to take advantage of terrain and provide concentrated firepower (Soodalter). Throughout the day on July 1st, Buford and his troops provided the Union Army with support and sufficient time to consolidate in the best defensible position available in the area. The“fish hook” on Cemetery Ridge was initiated with a layered defense beginning several miles away and collapsing back under the pressure of superior Confederate numbers.

Portrait of Brigadier General John Buford, Jr. (Wikimedia Commons)

Numerous roadways converged at Gettysburg. Four of these roads were hard-surfaced and therefore could facilitate more rapid movement of troops. Gettysburg was also near a railroad, presenting the potential for even greater mobility to whomever dominated the area (Longacre, p. 181–182).

Buford’s objective on June 29th was to secure the town of Gettysburg for consolidation of the Army. As such, Buford avoided prolonged combat when encountering a Confederate force (Longacre, p. 181). Another inconsequential clash occurred on the following day, June 30th, against a reinforced Confederate scouting party. Buford’s subordinate commanders viewed this as a positive sign, indicating the enemy’s unwillingness to press the issue. But Buford differed and correctly inferred that the lack of enthusiasm for fighting on the part of the Confederates indicated they had a better option than a hasty fight (Longacre, p. 182).

To confirm his suspicions, Buford conducted his own extensive reconnaissance of the terrain around the town. He talked with civilians and personally visited far-flung elements of his own forces, or pickets as they were called, to gather the most complete assessment of the enemy. He came to realize that a substantial force under General Hill was as close as 9 miles away (Longacre, p. 181–182, 184). Buford’s supervision of his forces on the eve of battle was comprehensive, and several aspects of what are today known as the US Army’s “troop leading procedures” were evident in his leadership example.

Buford set up his undersized element to force the Confederates to attack multiple superior defensive positions throughout the day.

He advised his men to notice campfires at night and the dust of approaching columns early in the morning. His men spread out in long, thin lines utilizing the available cover provided by the terrain. A small number of them had repeating rifles as well (Soodalter).

The defensive plan for the Union cavalry commander focused on the series of ridges surrounding the town. He determined that his initial defense would occur along McPherson and Seminary ridges to the north and west of the town, permitting his units to retreat and fight through the town and onto Cemetery Ridge if Confederate pressure was more than he and any Union reinforcements could handle (Longacre, p. 183). In this manner, Buford set up his undersized element to force the Confederates to attack multiple superior defensive positions throughout the day.

A modern rendering of a forward-thinking plan

Colonel Gamble was positioned in command of the western approach with a focus on McPherson’s Ridge and a reserve on Seminary Ridge. Gamble pressed an additional element 4 miles farther to the west on Herr Ridge, presenting a layered defensive on the most likely avenue of approach. The northern approach was under Colonel Devin’s command, who positioned forces along the compass points spanning northwest to northeast.

Battle commenced early on July 1st and Buford’s troops fought well against the Confederates. Confederate cavalry was not utilized effectively, enhancing the defensive advantages for the Union (Petruzzi). Late in the morning General Reynolds arrived to reinforce the troopers heavily engaged in vicinity of Gettysburg. While the Confederates succeeded in dislodging the Union Army from Seminary Ridge on the first day of battle, they could not press the issue effectively on Cemetery Ridge. Part of the defense of that position would be conducted by Buford’s troopers once again. As the Union Army regrouped on the ridge, Buford’s cavalry again exercised both mounted and dismounted maneuvers to confuse, impede, and distract the Confederates (Petruzzi).

General Buford died before the end of the war. While there are many important figures in the Civil War, he ranks among the most impactful even if not the most well-known. He designed, as much as any one person could, the Union’s most significant victory of the war.

Chris Zeitz is a veteran of military intelligence who served one year in Afghanistan. While in the Army, he also attended the Britannia Arms pub in Monterey. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Diplomacy from Norwich University. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of any U.S. Government agency.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Democracy: The Key to Avoiding Future Wars? (2)

In the Kantian framework, different kinds of agents pursue democracy at three levels: the individuals within a nation, the states in their relationships with one another and also with their citizens, and humankind. In this post we shall look at how individuals within a nation should behave if they want to truly abide by democratic principles. Should they rebel and when? Should they support war, and which type of war if any?