Hemispheric Alliances: Liberal Democrats and Cold War Latin America. Andrew J. Kirkendall. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2022.

In Hemispheric Alliances: Liberal Democrats and Cold War Latin America, Andrew J. Kirkendall provides a thoughtful analysis of the Latin America policy devised by liberal Democrats in the period running from the 1960s to 1980s. The book’s core argument is that liberals in the Democratic Party attempted to design and implement a foreign policy for Latin America that moved beyond the Cold War strategy of containment. Instead of containment, these policymakers sought to leverage U.S. power to foster economic development, democracy, and human rights in the region.

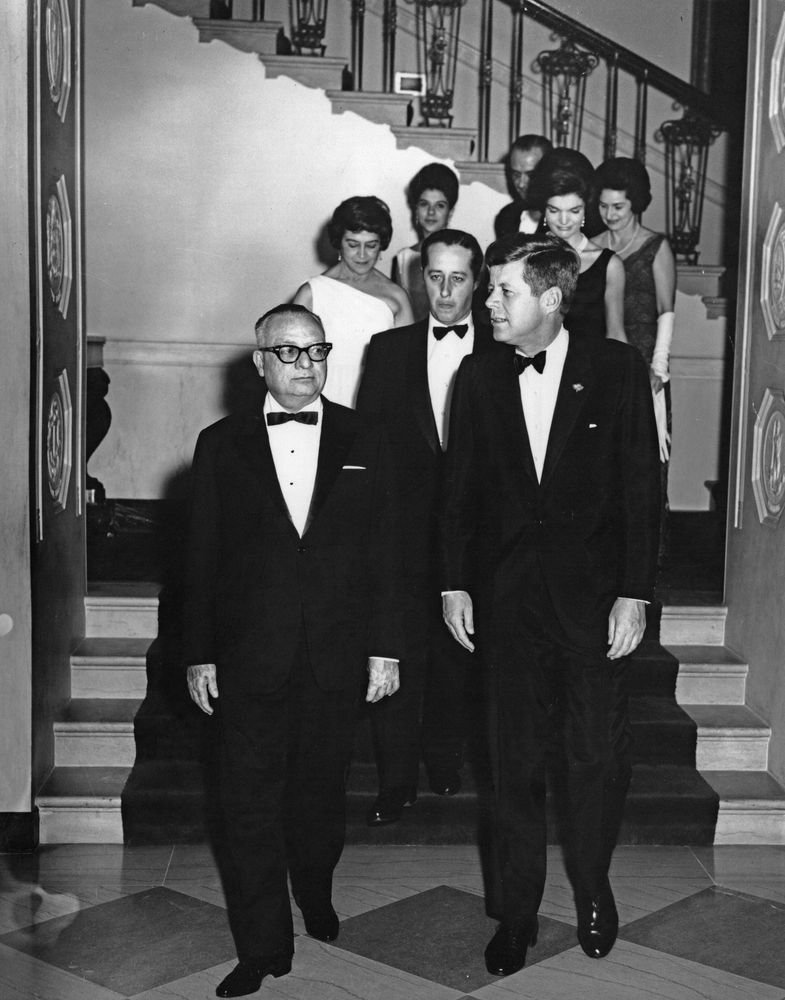

The highwater mark of this political project was John F. Kennedy’s famous Alliance for Progress initiative. The Alliance was devised in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, with the ostensible goal of transforming Latin American societies into stable democracies with broadly shared prosperity through economic development aid. The principal idea animating the initiative was that societies with less social inequality and greater political participation by a broader share of the population would be less susceptible to communist insurgency. Kirkendall’s book essentially provides a narrative history of both the Alliance itself during the presidency of John F. Kennedy, as well as the policy initiative’s half-life among liberal policymakers in the quarter-century following Kennedy’s 1963 assassination, with ample discussion of the foreign policy positions pursued by liberals inside and outside of the White House under each American president from Kennedy to Reagan. Beginning in the 1970s, the focus on social development policies and reduction of economic inequality gave way to the politics of human rights, until, with the Cold War over, a consensus formed in American politics that emphasized trade not aid.

There is much to commend in this book. The archival research is comprehensive and effectively presented for the non-specialist in each chapter. The mid-level analysis of this book is also quite good. If the book lacks a provocative or surprising central thesis, it is more than made up for by detailed description and analysis of various policymakers’ disagreements with one another, their evolving interpretations of events as they unfolded, and inevitable frustrations with external circumstances beyond the control of U.S. actors. Kirkendall’s careful reconstruction of internal policy disputes among the liberals clearly illustrates that some policymakers took more seriously than others the lofty rhetoric and outsized ambition of key liberal policies like the Kennedy administration’s Alliance for Progress or the Carter administration’s human rights initiatives.

If the book lacks a provocative or surprising central thesis, it is more than made up for by detailed description and analysis of various policymakers’ disagreements with one another, their evolving interpretations of events as they unfolded, and inevitable frustrations with external circumstances beyond the control of U.S. actors.

There are fascinating treatments in the book of a range of political actors. Familiar names—including the Kennedy brothers, Jimmy Carter, Frank Church, Tom Harkin, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.—all receive extended analysis from Kirkendall. I found Kirkendall’s discussion of Schlesinger’s long-standing fascination and engagement with Latin American politics and social problems particularly insightful. Readers may find themselves more drawn, however, to Kirkendall’s analysis of the careers of somewhat less well-known political actors like Frances Grant, of the Inter-American Association for Democracy and Freedom, or Oregon’s gadfly senator Wayne Morse. Both Grant and Morse are the subject of thoughtful treatments, and deserve greater attention from scholars of inter-American relations.

A great strength of the book is its engagement with the congressional politics of foreign policy, a topic unfortunately neglected by too many diplomatic historians. It is clear from Kirkendall’s research that congressional actors were key in shaping foreign policy positions staked out by a succession of presidents, secretaries of state, national security advisors, and other, less high-powered, executive branch functionaries. I left the book wishing for more scholarship from historians of U.S. foreign policy that takes Congress as seriously as Kirkendall.

Historians tend to neglect Latin America’s anti-communist left, in part owing to their awkward position in an overarching narrative of the Cold War as a time of extreme polarization, violence, and authoritarianism in Latin America.

Kirkendall’s careful analysis of Congressional politics dovetails closely with a particularly fascinating component of the book’s narrative: the formation of a transnational network of anti-communist center-left politicians in the Americas. Historians tend to neglect Latin America’s anti-communist left, in part owing to their awkward position in an overarching narrative of the Cold War as a time of extreme polarization, violence, and authoritarianism in Latin America. Yet, in this book, key figures like Venezuela’s Rómulo Betancourt and Costa Rica’s José Figueres, among others, appear as shrewd geopolitical actors, capable of carefully cultivating the trust of high-powered American liberals and influencing their approach to US policy in Latin America at key moments. On this point, Kirkendall’s book would have benefited from research in Latin American archives, though given the central focus of the study on liberal policymakers, the emphasis on U.S. archives is somewhat understandable.

Still, the book does frustrate at times. Kirkendall’s work would have benefited from deeper engagement with the classic observation that “politics stops at the water’s edge” and considered areas of continuity and agreement between Republican and Democratic political elites when it came to Latin America during the Cold War period.[1] There are many moments in the book where the notion of a foreign policy unique to liberal Democrats is quite clear, most especially in the book’s closing chapters on the Carter and Reagan-Bush years. But there are also points in the book where disputes among the liberal Democrats themselves come across as more or less as sharp as any disagreement that existed between the two parties when it came to foreign affairs, with the more idealistic figures like Morse or Schlesinger appearing as mere dissenting voices rather than as the key actors behind major decisions. Kirkendall can sometimes be a bit too trusting of the liberal political elites of the mid-twentieth century. At times, the book places too much emphasis on their high-minded rhetoric around democracy, freedom, and social justice. Kirkendall does not deny or ignore key events and developments in the 1960s like meddling in Chile’s 1964 elections or the funneling of resources into militaries that would go on to seize power in one Latin American country after another. However, he does occasionally downplay the extent to which these policies ran contrary to the ostensible goals of the Alliance.

Even so, this book provides an important contribution to the historiography of the period, providing novel perspectives on liberal approaches to U.S. foreign policy in Latin America during the Cold War for scholars and practitioners working on U.S.-Latin American relations to consider.

Miles Culpepper is a lecturer in the history department at UC Berkeley, where he also earned his PhD. He is currently writing a book on Guatemalan exiles during the Cold War period, based on his dissertation research.

The Strategy Bridge is read, respected, and referenced across the worldwide national security community—in conversation, education, and professional and academic discourse.

Thank you for being a part of the The Strategy Bridge community. Together, we can #BuildTheBridge.

Header Image: Alliance For Progress, La Morita, Venezuela 1961 (Cecil Stoughton).

Notes:

[1] “Politics stops at the water’s edge” is a aphorism attributed to Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg. https://www.languagehumanities.org/what-does-politics-stops-at-the-waters-edge-mean.htm