“Pity the warrior who is contented to crawl about in this beggardom of rules, which are too bad for genius, over which it can set itself superior, over which it can perchance make merry!” - Carl von Clausewitz [1]

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland can help us better understand the experience of Clausewitzian genius. Now, this sounds about as illogical as Lewis Carroll’s famous riddle, uttered by the Mad Hatter: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” But unlike the riddle, which was initially constructed without an answer, the concept of genius links Clausewitz and Alice without artifice. While Clausewitz’s “field of genius...raises itself above rules,” Wonderland is a fantastical space that enables Alice to raise herself not only above rules, but also sense.[2] To see how this is so, we can appeal to Alice and her encounters in Wonderland to highlight the complexity found within military genius. But first we must locate genius in the space where theory fails to map onto reality.

Carl von Clausewitz’s On War is more than a description of a theory of war. It is an exploration of why war in reality fails to conform to its theoretical expectations as much as it is an exposition and defense of a specific theory. Moreover, Clausewitz probes and prods the limits of the application of any theory of war to determine how and to what extent a theory of war is possible, and how—despite its inability to fully model reality—it remains necessary and valuable. Clausewitz is arguing against the possibility of establishing “maxims, rules, and even systems for the conduct of War”—in other words, the specifics of fighting in war.[3] War is boundless; it “has no definite limits in any direction.”[4] Thus, any attempt to circumscribe the choices, to delineate the how of fighting, are bound to miss—as a consequence of war’s limitless nature—the innumerable realities inherent within any violent clash of human forces.

Clausewitz identifies three “peculiarities” that make it “a sheer impossibility to construct for the Art of War a theory which, like a scaffolding, shall ensure to the chief actor an external support on all sides.”[5] These reasons are consequences derived from his trinity of chance, reason and emotion: (1) the uncertainty of information (2) the reciprocal interaction with the enemy, and (3) the power of the human spirit or morale. Arguing against the likes of Jomini’s positional geometry, Clausewitz is keen to head off definitive prescriptive theory—essentially a rule-book—because such “positive theory” attempts to identify “determinate qualities” from which it can promote certain actions. To Clausewitz, this attempt is misguided because “ in War all is undetermined.”[6] On War thus explains why a positive theory cannot be formulated. But Clausewitz’s theory does not preclude a “chief actor” with a special glance—that coup d’oeil—from devising a decision without any theoretical framework to reinforce the action.[7]

Clausewitz is not implying that theories of war are impossible, only that at their limits something unforeseeable and intangible determines action. This is genius. Without a framework that directs flank here or strike now, talent must establish its own self-prescription. Specifically, Clausewitz notes that what is possibly explainable by theory will appear naturally in genius: Theory for “the reflecting mind [is] the leading outline of its habitual movements…[rather than] the way in the act of execution.”[8] The external support of theory, which Clausewitz claims cannot be fully formulated, is now provided by the internal knowledge of the chief actor, whose rapid self-reflection bridges the gap between finite theory and effective action. It is only “away from this scaffolding of theory and in opposition to it” that the “[chief actor] is thrown upon his talent.”[9]

Of course, not all who are thrown onto their talent, instinct, and knowledge produce genius. The better the decision—as judged retrospectively, historically—the closer it approaches to genius. Few are capable. As Clausewitz’s muse, Napoleon is the paragon of military genius. General James Mattis, who arguably might be considered another, has said, “I spent 30 years getting ready for that decision that took 30 seconds.” These geniuses act above rules, without the scaffolding of theory, and in circumstances where there is nothing other than themselves, the situation, and the context, where “anywhere and at every pulse-beat [they] may be capable of giving the requisite decision from [themselves].”[10]

Turning now to Alice, we jump ahead a few decades to 1865, during which the mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, under the pseudonym of Lewis Carroll, wrote Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The work is exemplary of the Victorian supernatural genre, constitutes the beginning of the golden era of children’s literature, and represents the paradigm for literary nonsense. Wonderland follows Alice as she falls down the rabbit hole, wherein she confronts the living reactions of phantasmal creatures from the White Rabbit and the Cheshire Cat to the Mad Hatter and the Queen of Hearts, whose moral forces and mercurial emotions rival those of capricious children like herself. Additionally, into the work Carroll weaves wordplay and logic games that juxtapose theory and reality, sense and nonsense. It is through these tensions that Alice encounters her capacity for genius.

On top of being susceptible to whims of chance and uncertainty (and the author’s pen), Alice faces an added peculiarity: nonsense. Nonsense is that which lies beyond both sense and logical deduction or inference; it is not irrational, but rather non-rational. Its meaning does not fall within our traditional categories or subscribe to typical referents. Nonsense transcends the limits of our theory as it transcends the limits of any sense. Luckily, Alice identifies quickly that Wonderland does not conform to the same rules as her former reality. Shortly after her fall, Alice reaches the point where “so many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that [she] had begun to think that very few things indeed were really impossible.”[11] Since Alice abides by the uncanny (finding the strange in the familiar and the familiar in the strange), she provides her own solutions. Eventually, Alice surrenders to the facts of the matter, consenting to both the capabilities and limitations of her perception of Wonderland.

Alice and a bottle labeled, "Drink Me," John Tenniel, from The Nursery Alice.

Chief actors, like Alice, must be able to at once acknowledge the limits of their knowledge and then produce the key from within by blending that knowledge and self-reflection in new and interesting ways. This type of reasoning exceeds logical deduction and instead trusts the creative interplay of an unconscious stream of unsystematic inquiries into the situation at hand. In Wonderland, this mode of reasoning can be seen in Alice’s many metamorphoses. After Alice falls down the rabbit hole, she ventures down passages where her curiosity leads her to a “little golden key” that opens a small door with a “passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw.” Unfortunately, the door is “not much larger than a rat-hole,” and Alice concludes that “even if [her] head would go through…it would be of very little use without [her] shoulders.” And yet she finds a solution. While hoping to find “a book of rules for shutting people up like telescopes,” Alice instead finds a bottle with the label “DRINK ME.” Just as any good genius should, she tries to appeal to formal theory, her desired book of rules, before dispensing with the scaffolding of theory and seeking the answer within herself. Alice determines—in accordance with “simple rules” that she had read and learned from cautionary children’s tales—that the bottle contains no poison, as it is not marked “poison.” With this conclusion she “venture[s] to taste it” and “very soon finishe[s] it off.” After downing it, Alice, like a telescope, becomes “now the right size for going through the little door.”

Chief actors...must be able to at once acknowledge the limits of their knowledge and then produce the key from within by blending that knowledge and self-reflection in new and interesting ways.

Flexibility, a fundamental requirement for genius, is the ability to respond to the changing context by modifying oneself, one’s actions, or one’s preconceived notions. In the passage, Alice experiences the figurative flexibility of genius as a literally flexible transformation. As Alice continues her journey she drinks potions, eats cakes, and nibbles mushrooms in order to adapt to her surroundings. Yet, there is more to genius than pure flexibility, rationality is also required. Albeit susceptible to childish whims and curiosity, Alice still utilizes carefully-thought out sets of reasons for her actions even in a non-rational nonsensical world. Reasons must serve to justify the deviation from the rulebook or the scaffolding of theory and identify how to flex and flux around the Clausewitzian peculiarities that emerge from reality.

The Caterpillar and Alice, John Tenniel, from The Nursery Alice.

Geniuses need not seek out guidance from a caterpillar to nibble on mushroom in order to shrink or grow. But they must be able to think and act with sufficient—though not gratuitous—flexibility. With this flexible rationality, geniuses can reason out new possibilities and seek to fulfill Clausewitz’s method in which “[k]nowledge must, by this complete assimilation with his own mind and life, be converted into real power.”[13] And Alice certainly proves quite powerful by the end. When the Queen jeers, “Off with her head!” Alice responds quite cavalierly: “‘Who cares for you?’ said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) ‘You’re nothing but a pack of cards!’” Here, Alice reasserts her natural self and her knowledge of the way the world ought to work, bridging the gap between expectations and reality. Reaching this point of acceptance is difficult, but may be the first step towards genius.

Clausewitz preserves some preeminence of theory by noting that we ought not to contradict the larger principles established by theory unless there is good reason.

Clausewitz notes, and Carroll would almost certainly agree, “What genius does must be the best of all rules, and theory cannot do better than to show how and why it is so.”[14] But Clausewitz preserves some preeminence of theory by noting that we ought not to contradict the larger principles established by theory unless there is good reason. Otherwise potential geniuses devolve into hermits spouting riddles like the Mad Hatter. And the only good reason can come from genius. Therefore, let us strive to be a bit more like Alice. Let us balance theory and reality like she balances fantasy and reality. Let us grow and shrink with the required finesse, a true sense of self, and the ability to reconcile what currently is with what ought to be. Only then, provided we demonstrate sufficient flexible rationality, can we convert our knowledge and experience into real power.

Olivia A. Garard is an officer in the US Marine Corps. She has an MA in War Studies from King's College London. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or the U. S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

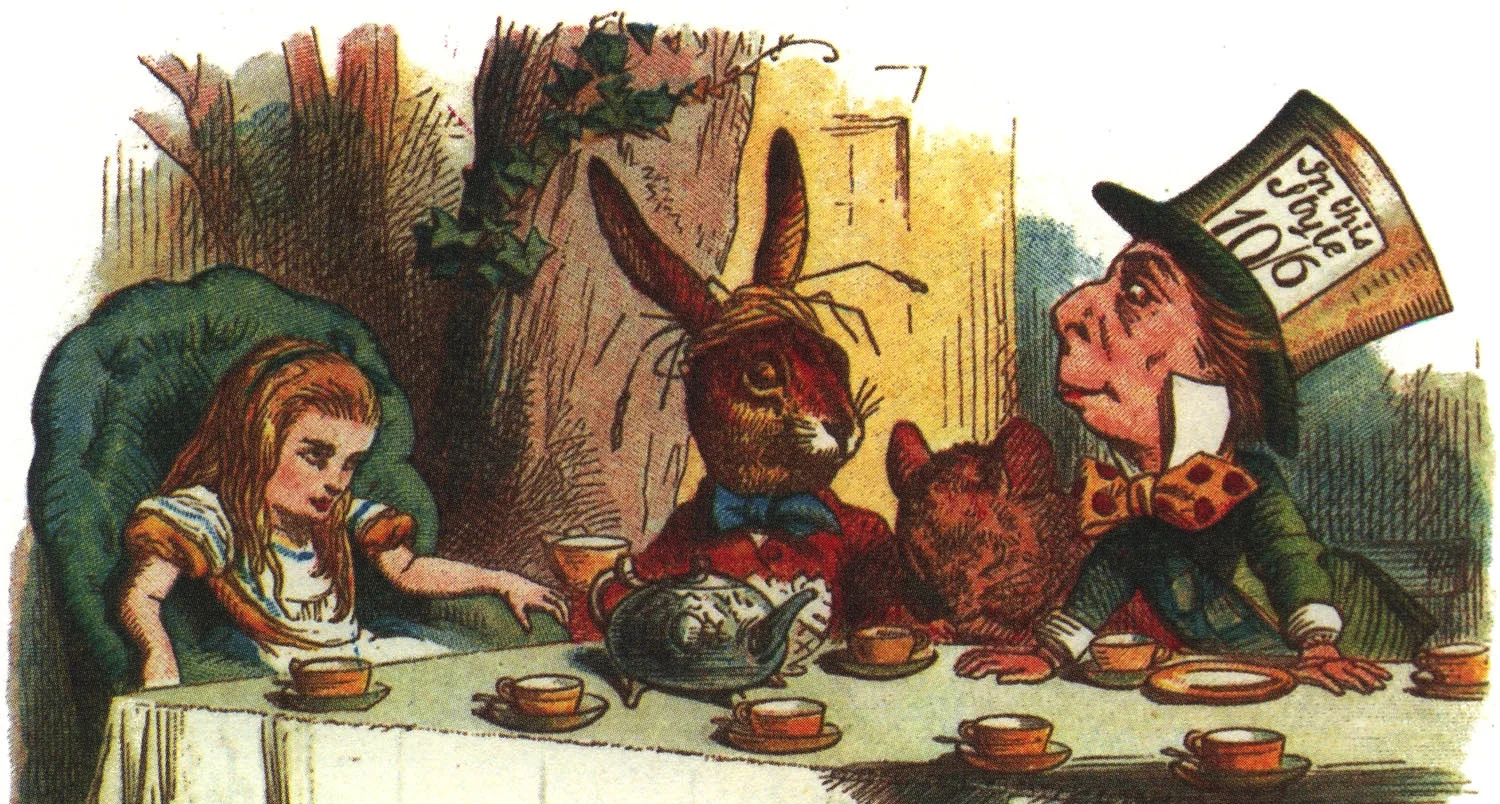

Header Image: Alice, the March Hare, the Dormouse and the Mad Hatter. Colorized version of an illustration by John Tenniel for The Nursery Alice (1890).

Notes:

[1] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. Colonel J.J. Graham (New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2004): 81.

[2] Ibid., 80.

[3] Ibid., 78.

[4] Ibid., 79.

[5] Ibid., 85.

[6] Ibid., 80. Emphasis added.

[7] Ibid., 85.

[8] Ibid., 87.

[9] Ibid., 85.

[10] Ibid., 94.

[11] Carroll, Lewis, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, (New York: The Modern Library, 2002): 7.

[12] Clausewitz, 94.

[13] Ibid., 81.