The Strategist: Brent Scowcroft and the Call of National Security. Bartholomew Sparrow. New York: PublicAffairs Books, 2015.

Why It Matters

When they first met Air Force Colonel Brent Scowcroft, the other military aides working for President Richard Nixon described him as small, meek-looking, soft-spoken, and as someone who failed to impress (67). People who knew him well understood him to be calm, patient, modest, and caring. Yet, this polite and unpretentious man is regarded as one of the foremost political strategists and statesmen of the 20th century. In The Strategist: Brent Scowcroft and the Call of National Security, University of Texas Professor of Government Bartholomew Sparrow’s account of Scowcroft delves into the relationships that defined him, suggesting Scowcroft was a duty-fulfiller, a “fixer” rather than a policy maker, and a man with vast emotional intelligence.

Executive-level Politics and Relationships

Scowcroft first entered the world of executive-level decision-making as a military assistant to President Nixon in December 1971. His calm demeanor and extensive knowledge of international politics and history quickly gained the attention of the National Security Council (NSC) Director, Henry Kissinger, who asked him to be his deputy. Working for Kissinger was not easy; he demanded his staff be at the White House by 6:30 in the morning, and stay until 11:30 at night (82). Kissinger would publicly demean others and “was perpetually concerned with intrigue” (83). Sparrow cleverly weaves through the multifaceted and devious relationships inside the Nixon administration and shows how they resonated throughout the entire staff and into foreign policy decision-making.

The Nixon administration’s immense foreign policy victories: détente with the Soviet Union, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, and the diplomatic opening of China, led to Time Magazine selecting both Nixon and Kissinger as “Man of the Year” in 1972. Yet, despite public praise, Nixon “resented Kissinger’s celebrity and tendency to take credit for the administration’s achievements” (99). Nixon’s early achievements were quickly overshadowed by the “dominant foreign policy issue of the era, the war in Vietnam,” (77) and the infamous Watergate Scandal.

Sparrow shows that after Kissinger selected Scowcroft as his deputy, Scowcroft was immensely loyal; he refused to spy on Kissinger and report his findings back to his superiors in the Pentagon (81). The relationship between the two men was very close—in 1974 Kissinger asked Scowcroft to be the best man in his wedding—yet Kissinger also made sure Scowcroft stayed in his lane. When “Kissinger found out that Scowcroft was invited to a black-tie dinner with the ambassadors from the Organization of American States, he remarked...’that’s a little more above your level.’” (88).

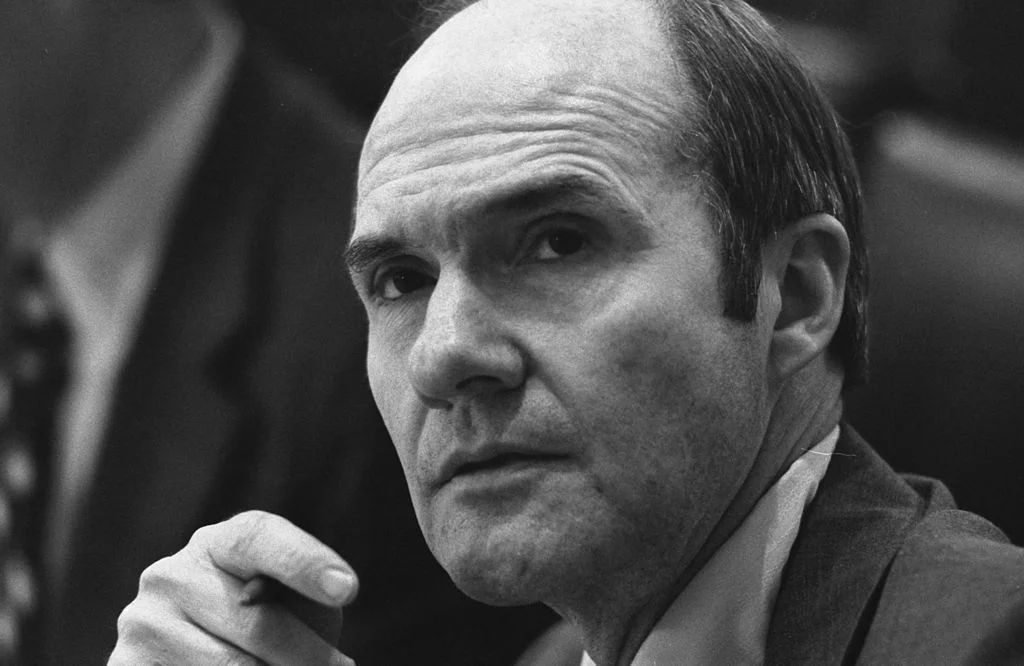

Deputy National Security Advisor Gen. Brent Scowcroft in his White House office, 1968 (Kennerly Archive)

One of Sparrow’s oddest disclosures concerns President Nixon’s late night drunk dialing. According to Sparrow, “Scowcroft, who was one of the few people Nixon trusted, sometimes received odd late-night demands from him…After a martini or two, Nixon would order all sorts of unusual things to be done…the next day the president would almost always never mention the evening before” (101). Scowcroft would pretend the incident never happened. President Nixon also had remarkably strange demands, “…one evening Nixon had asked him [Kissinger] to kneel down with him and pray…Kissinger said the president was slurring his words” and didn’t want anyone to know that he was “not strong” (101).

Working Inside the NSC

Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft tries to explain to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger why 11 Marines were stranded on the roof of the U.S. Embassy. Washington, D.C., April 29, 1975 (Kennerly Archives)

Sparrow also has several revelations on Scowcroft’s role in other Republican administrations. In some cases he details blow-by-blow deliberations of the NSC—the actors and how they interacted with each other. For instance, students of political science and American government will enjoy Scowcroft’s recollection of an incident in which a general officer’s input collided with a civilian superior. In this case it was 1990, and the relationship between Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Colin Powell was particularly tenuous; after Powell offered contentious military advice, “Cheney thought it was out of place for Powell to be telling his civilian superiors how to conduct U.S. national security policy—and later that day, at the Pentagon, he told Powell precisely that” (389).

Scowcroft also reveals the difficulty of working with external actors, such as the Israelis. In the run up to Desert Storm, President George H.W. Bush found the Israeli prime minister “cold and arrogant” (412). Sparrow carefully notes the constructivist nature of international relations: the importance of relationships between people in positions of power and the influence they wield. Historians and scholars of the first Gulf War will be particularly interested to note that the Soviet premier, Mikhail Gorbachev offered a peace initiative to the United States before the invasion. According to Scowcroft, the Soviets “didn’t want to see the United States get a ‘big victory’ or embarrass the Soviet Union by revealing how poorly the Soviet equipment matched up against the American material” (412).

On Iraq

National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft, Secretary of Defense Richard V. Cheney, President George H.W. Bush and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, during Operation Desert Storm, 1991. (Carol T. Powers)

Scowcroft was an early skeptic of how a post-Saddam Hussein Iraq would function and the consequences for the entire Middle East. In 1990, during the first Bush administration, after Saddam’s ill-fated invasion of Kuwait, Scowcroft explains that no one the NSC staff, including himself, “wanted a partition of Iraq,” arguing instead that an “intact and secular Iraq functioned as a regional balance to the religious, Shi’ia-dominated Iran” (416).

Scowcroft’s decades of work across four Republican administrations surely gave him name-recognition, legitimacy, and a legacy of allegiance to the party. Therefore, it must have seemed “grossly out of character” to many in the Republican establishment when twelve years later, in August 2002, Scowcroft famously penned a New York Times Op-Ed arguing against an expensive and bloody occupation in Iraq. But, instead of reveling in an “I told you so” moment several years later, Scowcroft would go on to advise and assist the George W. Bush and even the Barack Obama administrations the best he could.

Who Should Read It

Sparrow’s account of Scowcroft is full of insight and surprises. Readers will take pleasure in Sparrow’s depiction of the NSC debates, executive-level relationships, and the nuanced recollections of a consummate strategist. Anyone interested in understanding the unique role of the NSC in foreign policy and executive-level decision-making during the Nixon, Ford, Reagan, or first Bush administrations will be interested Sparrow’s work. This book also has practical use for journalists, political scientists, as well as students of U.S. security strategy, foreign policy, and American government.

Dr. Diane Maye is a member of the Military Writers Guild and frequently writes about U.S. foreign policy, Iraqi politics, and grand strategy. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. The opinions expressed are the author's and do not reflect the official position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.