The 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy appeared to bring deterrence back: departing from its predecessor, the document prioritized the concept by including “preserving peace through strength” as a vital national interest.[1] From nuclear weapons to cyberspace, the strategy emphasized the logics of denial and punishment, which were hallmarks of the classical deterrence theory that emerged after World War II.[2] However, recent thinking on deterrence has evolved beyond these simple logics. Now emerging concepts such as tailored deterrence, cross-domain deterrence, and dissuasion offer new ideas to address criticisms of deterrence in theory and practice. Therefore, the most vital question for the new administration is: how should the U.S. revise its deterrence policy to best prevent aggression in today’s complex environment? A review of the problems and prospects in deterrence thinking reveals that in addition to skillfully tailoring threats and risks across domains, U.S. policymakers should dissuade aggression by offering opportunities for restraint to reduce the risk of escalation.

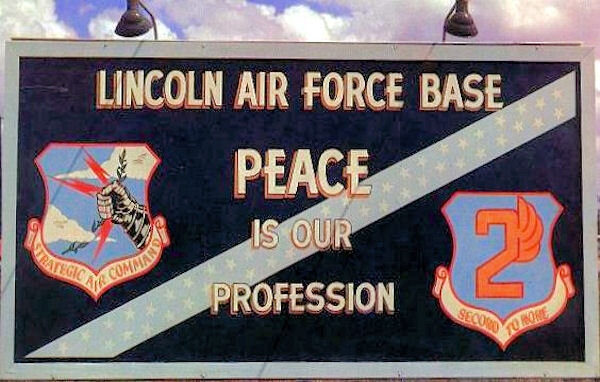

Postcard of SAC Sign Lincoln AFB NE 1960. (Wikipedia)

Despite its flaws, early deterrence thinking was born out of necessity. The advent of nuclear weapons required scholars and policymakers to discover ways to avoid nuclear Armageddon. Most scholars and practitioners favored deterrence on moral and practical grounds: saving lives and treasure is clearly preferable to expending them, which is why the motto of the U.S. military’s primary deterrence instrument has remained “Peace is Our Profession…”[3] Though deterrence was a significant instrument of statecraft during the Cold War, critics have long challenged that the strategic concept is a blunt tool and incompatible with human or organizational biases, misbehaving or irrational actors, or novel technologies. Instead of contributing to stability, threats of punishment could spiral into escalation. Moreover, skeptics note that empirically testing deterrence is challenging—if not impossible—given that cases of deterrence success or failure are susceptible to selection bias and peace is largely overdetermined.[4]

However, the study and practice of deterrence deserves refinement if policymakers and scholars desire to continue the unprecedented era of great power peace.

As the Latin deterre means to “frighten from or away,” a strategy that manipulates threats of future pain to persuade a thinking adversary from revising the status quo is sure to have theoretical and practical problems.[5] However, the study and practice of deterrence deserves refinement if policymakers and scholars desire to continue the unprecedented era of great power peace. Looking back on the Cold War, Lawrence Freedman observed, “deterrence seemed to work, maybe better in practice than in theory.”[6] Looking forward, the authors of the next security strategy should incorporate updates in deterrence theory to make the concept work better in practice.

Problems in Deterrence Theory: Biases and Escalation, Misbehaving Actors, and Novel Technologies

The first concern with classical deterrence theory is that its assumptions of rational behavior belie the misperceptions and biases that could lead to escalation instead of stability. This line of criticism developed during the third wave of deterrence thinking, when scholars questioned simplistic assumptions and game-theoretic models developed by those in the first two waves.[7] These scholars highlighted rational deterrence theory’s faulty assumptions through case studies, pointing to several biases that are inherent in human psychology, organizations, and bureaucracies. At the individual level, leaders often turn to prior beliefs and historical analogies to make sense of current crises, which may be flawed comparisons to the present.[8] The limits of human cognition and the inability to accurately interpret an adversary's intentions or signals further undermine classical rationality.[9] Worse, deterrence signals may be misinterpreted as impending attacks, intensifying the security dilemma and resulting in escalation. Even more recent work has explored how the psychology of revenge—or the “intrinsic pleasure that one expects to experience striking back”—explains the willingness of leaders to retaliate even at the risk of their own destruction.[10]

Saddam Hussein, Kim Jung Il, and the Ayatollah typify the rogue leaders that critics feared would not respond rationally to incentives, willing to risk survival to fulfill their aggressive personal or ideological goals.

The second challenge emerges from what Jeffrey Knopf labels the fourth wave of deterrence thinking, which emerged after the terrorist attacks on 9/11 and consumed itself with what to do about asymmetric threats or non-conforming actors who would not behave according to rational deterrence theory.[11] Saddam Hussein, Kim Jung Il, and the Ayatollah typify the rogue leaders that critics feared would not respond rationally to incentives, willing to risk survival to fulfill their aggressive personal or ideological goals. Religiously motivated terrorists were viewed as undeterrable because they would ignore costs, possess little territory or few citizens to hold at risk, and reject the goal of survival (at least suicide bombers), which are all hallmarks of classical deterrence thinking.[12]

If a strategy of deterrence by punishment rests on the ability to threaten to inflict pain on a target, that threat becomes far less credible when the attack is anonymous.

Today’s third challenge emerges from disruptive technology and new domains. As Joseph Nye recounts, some have argued that deterrence is challenging—if not impossible—in cyberspace given the difficulty in attribution and credibility of potential responses.[13] If a strategy of deterrence by punishment rests on the ability to threaten to inflict pain on a target, that threat becomes far less credible when the attack is anonymous. Ben Buchanan describes how cyber operations are more effective as tools of clandestine espionage, sabotage, and destabilization rather than reliable signals of capability and credibility.[14] Denial is also difficult and expensive in cyberspace, though recent research has pointed out that cyber operations are far less offensively-dominant than assumed since organizational practices and skills make offensive operations difficult.[15]Advances in robotics may also be problematic for deterrence: former U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work argued that unmanned weapon systems assuage human fears of casualties in war, undermining the ability to impose costs on an aggressor.[16]

Updates in Deterrence Thinking: Tailored Deterrence, Cross-Domain Deterrence, and Dissuasion

To address the problems of rogue states, terrorists, inadvertent escalation, and novel technologies, deterrence thinkers have introduced three updates: tailored deterrence, cross-domain deterrence, and dissuasion. After the attacks on 9/11 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the George W. Bush administration proposed a new strategy labeled “tailored deterrence” in the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review to manage the threat of states and terrorists wielding weapons of mass destruction.[17] Elaine Bunn notes that this concept moved away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach from the Cold War by taking into account the adversary’s society, culture, and leadership when manipulating the costs and benefits of deterrence.[18] Obviously, U.S. deterrence operations should be applied differently from China to Russia to Al Qaeda to anonymous hackers. This concept grew as additional research enhanced understanding of the role strategic culture plays in a state’s perception of costs and benefits and developed qualitative profiles of decision-makers to understand their views of the status quo, what assets they hold dear, how they view an issue’s stakes, and how they cognitively process deterrent signals.[19] By examining what leaders or organizations say and believe, deterrence thinkers hope to avoid “mirror-imaging” Western political values that may confuse the logical link between beliefs and actions.[20]

…President Eisenhower’s “massive retaliation” offset strategy threatened nuclear war in response to a Soviet land invasion…

The second approach intersects with the desire to tailor capabilities by considering how deterrence could span across domains.[21] Though the concept of cross-domain deterrence is not new—President Eisenhower’s “massive retaliation” offset strategy threatened nuclear war in response to a Soviet land invasion—the growing salience of cyber, space, and information domains expands the opportunities and risks of aggression. Cross-domain deterrence would include non-military tools such as legal measures to prosecute would-be terrorists and threats of economic sanctions to deter state-sponsored hackers. Policymakers who fear China and Russia’s ability to undermine US information superiority through anti-satellite weaponry need to consider denial and punishment strategies through cyberspace and on land.[22] Within the challenging domain of cyberspace, defenders could encourage shared norms of appropriate behavior and leverage entanglement to spread the costs of aggression with the challenger.[23]

Finally, dissuasion is the broadening of deterrence to incorporate non-military means as well as rewards and compromises instead of mere threats.[24] Though reassurance is sometimes framed as a direct alternative to deterrence, students will note that even classical theorists considered off-ramps and compromises.[25] Thomas Schelling emphasized the need to reassure an opponent that good behavior would not result in punishment, while others made the case that promises of American compromises and rewards—and not just threats—resolved the Cuban Missile Crisis.[26] Dissuasion reflects a similar logic of a “firm but flexible” strategy, which Paul Huth argues is more effective in preventing war than an unyielding deterrent posture.[27] Even the current U.S. joint operating concept for deterrence emphasizes the need to “encourage adversary restraint” in addition to denying benefits and imposing costs.[28] Another form of dissuasion, as laid out in the 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review, is the attempt to convince an adversary not to compete with the U.S. in the first place, such as by deterring the acquisition or enhancement of advanced weapons.[29] The overlap between both forms of dissuasion is the attempt to reduce the intensity of the competition, either through compromises or by avoiding the situation altogether.

Updating Deterrence in the Next Security Strategy

Despite the centrality of deterrence in the 2017 National Security Strategy, the document focused too narrowly on denial and punishment. For instance, in the domain of cyberspace, the strategy calls for hardening the government’s information networks, layering defenses in the public and private sectors, and imposing “swift and costly consequences” on attackers.[30] However, the document largely downplays deterrence across domains, as well as opportunities to establish institutions that encourage restraint in other states. The new security strategy should continue to prioritize the need to compete against major powers without forgetting the importance of tailoring capabilities to different types of state and non-state actors, including rising powers such as China and Russia. The new strategy should also focus less on military tools and more on expanding the number of instruments to deter across domains. Threats in the cyber domain, for example, may require diplomatic, legal, or economic sanctions instead of mere cyber denial or punishment. Finally, and most importantly, the authors of the next strategy should be willing to offer positive inducements to lower the risk of escalation. Institutions that can codify acceptable behavior with regard to autonomous weapons and in the domains of space and cyberspace may offer opportunities for cooperation to limit the severity of the security dilemma. Without these updates, U.S. strategy may not be up to the task of managing the gravest challenges in international politics.

Kyle J. Wolfley is an Assistant Professor of International Affairs in the Department of Social Sciences at West Point and an U.S. Army officer. He is the author of the forthcoming book Military Statecraft and the Rise of Shaping in World Politics. He holds a Ph.D. in Government from Cornell University. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Minot AFB, North Dakota, 2021 (Senior Airman Josh Strickland).

Notes:

[1] Donald J. Trump, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, D.C.: The White House, December 2017), 3-4, 25-35, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

[2] Strategies of denial deter by convincing an opponent that aggression is too costly and futile, while punishment deters by threatening retaliation after the aggression takes place. Glenn H. Snyder, Deterrence and Defense: Toward a Theory of National Security, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), 14-16. Snyder attributes this distinction to Robert E. Osgood, “A Theory of Deterrence,” unpublished manuscript, 1960.

[3] General John E. Hyten, “2017 Deterrence Symposium Opening Remarks,” US Strategic Command: Speeches, July 26, 2017, 2017 Deterrence Symposium Opening Remarks > U.S. Strategic Command > Speeches (stratcom.mil).

[4] James D. Fearon, “Selection Effects and Deterrence,” International Interactions 28, no.1 (2002): 5-29.

[5] Lawrence Freedman, Deterrence (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 7.

[6] Freedman, Deterrence, 13.

[7] Robert Jervis, “Deterrence Theory Revisited,” World Politics 31, no. 2 (January 1979): 289-324.

[8] Robert Jervis, “Hypotheses on Misperception,” World Politics 20, no. 3 (April 1968): 470-471. See also Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978).

[9] Robert Jervis, Richard Ned Lebow, and Janice Gross Stein, Psychology and Deterrence (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1985).

[10] Rose McDermott, Anthony C. Lopez, and Peter K. Hatemi, “Blunt Not the Heart, Enrage It,” Texas National Security Review 1, no. 1 (December 2017): 68-88.

[11] Jeffrey W. Knopf, “The Fourth Wave in Deterrence Research,” Contemporary Security Policy 31, no. 1 (2010): 1-33.

[12] For an expression of these concerns, see “Text of Bush’s Speech at West Point,” June 1, 2002, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/06/01/international/text-of-bushs-speech-at-west-point.html.

[13] Joseph S. Nye Jr. “Deterrence and Dissuasion in Cyberspace,” International Security 41, no. 3 (Winter 2016/2017), 45-46, 49-52.

[14] Ben Buchanan, The Hacker and the State: Cyber Attacks and the New Normal of Geopolitics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020), 7-9.

[15] Rebecca Slayton, “What is the Cyber Offense-Defense Balance? Conceptions, Causes, and Assessment,” International Security 41, no. 3 (2017): 72-109.

[16] Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “War Without Fear: DepSecDef Work on How AI Changes Conflict,” Breaking Defense, May 31, 2017, https://breakingdefense.com/2017/05/killer-robots-arent-the-problem-its-unpredictable-ai/.

[17] U.S. Department of Defense, Quadrennial Defense Review Report (February 6, 2006), 49-51.

[18] M. Elaine Bunn, “Can Deterrence Be Tailored?” Strategic Forum 225 (January 2007): 1-8.

[19] Kerry Kartchner and Jeannie Johnson, eds., Strategic Culture and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Culturally Based Insights into Comparative National Security Policymaking (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Keith Panye, “The Fallacies of Cold War Deterrence and a New Direction,” Comparative Strategy 22, no. 5 (2003): 411-28.

[20] Michael McVicar, “Profiling Leaders and Analyzing their Motivations,” Phalanx 44, no. 4 (December 2011): 6-8.

[21] Jon R. Lindsay and Erik Gartzke, eds., Cross-Domain Deterrence: Strategy in an Era of Complexity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[22] Benjamin W. Bahney, Jonathan Pearl, and Michael Markey, “Antisatellite Weapons and the Growing Instability of Deterrence,” in Cross-Domain Deterrence: Strategy in an Era of Complexity, eds. Jon R. Lindsay and Erik Gartzke,(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 138-143.

[23] Nye, “Deterrence and Dissuasion in Cyberspace,” 58-63.

[24] Michael J. Mazarr, Arthur Chan, Alyssa Demus, Bryan Frederick, Alireza Nader, Stephanie Pezard, Julia A. Thompson, and Elina Treyger, What Deters and Why: Exploring Requirements for Effective Deterrence of Interstate Aggression (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation), 2018. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2451.html.

[25] Janice Gross Stein, “Reassurance in International Conflict Management,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 3 (Autumn 1991): 431-451.

[26] Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966), 74-75; Alexander L. George and William E. Simons, eds., The Limits of Coercive Diplomacy, 2nd Ed. (Boulder: Westview Press, 1994).

[27] Paul K. Huth, “Deterrence and International Conflict,” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1999): 37-39.

[28] U.S. Department of Defense, Deterrence Operations Joint Operating Concept, Version 2.0, December 2006, 27-28.

[29] Andrew F. Krepinevich and Robert Martinage, Dissuasion Strategy, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (May 6, 2008), https://csbaonline.org/research/publications/dissuasion-strategy.

[30] Trump, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, 12-14, 25-32.