President Franklin D. Roosevelt was determined to avenge the December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor. The attack enraged and shocked the American public. It seemed the national mood would only worsen as news of Japan’s follow-on victories at Wake Island and in Thailand, Hong Kong, Manila, and Singapore made its way onto American air waves and newspapers. Japan appeared unstoppable.[1] To prevent the national mood from deteriorating further, President Roosevelt pressed his advisors for a military win to raise morale and support for the inevitable two-front war. The president insisted they “find ways and means of carrying home to Japan proper, in the form of a bombing raid, the real meaning of war.”[2] His advisors developed a bold plan to launch sixteen modified land-based bombers from an aircraft carrier, and eighty brave men stepped forward to carry out the first strike on Japan’s homeland. That strike would become known as the famous Doolittle Raid.

The Doolittle Raid’s place among the time-honored traditions of courageous military action is secure, but its impact on America’s ultimate victory in the Pacific remains unclear.

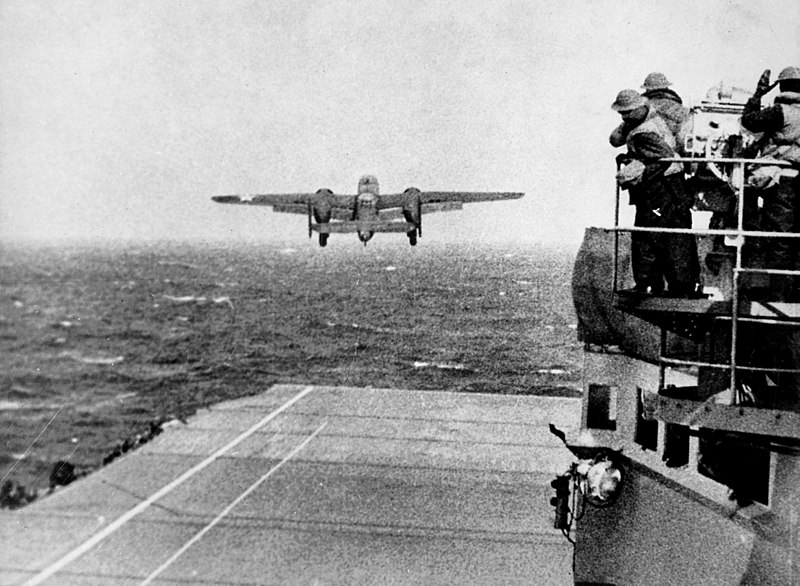

Despite the long odds, Doolittle’s Raiders slipped through Japan’s defenses on April 18, 1942 to deliver a surprise blow. The raiders bombed several Japanese cities including Kobe and Yokohama, but Tokyo was perhaps the most significant because it was the Emperor’s home and the nation’s capital. In stunning fashion, the raid answered President Roosevelt’s call for retaliation and soothed America’s wounded pride. The Doolittle Raid’s place among the time-honored traditions of courageous military action is secure, but its impact on America’s ultimate victory in the Pacific remains unclear.[3]

Although the raid inspired books like Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo and its theatrical adaptation, and the film Destination Tokyo, the actual military results of this legendary mission are dubious. Damage inflicted by the raid fell far short of a Japanese military setback.[4] The loss of all the customized B-25B bombers and Japan’s resulting hyper-vigilance together suggested a repeat surprise attack would probably fail.[5] Moreover, not even the ensuing three years of hard fighting could subdue the Japanese; only the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagaski in 1945 proved decisive. If the raid produced lackluster military results, and America undertook the raid mainly to avenge Pearl Harbor, what is the strategic importance of this legendary military operation?

Strategic Importance Defined

In Modern Strategy, Colin Gray defines strategy as “the bridge that relates military power to political purpose; it is neither military power per se or political purpose."[6] In practice, military power alone is rarely sufficient to achieve policy; simultaneous and synchronized application of multiple elements of national power is necessary.[7] Consequently, assessing the strategic relationship of a singular military event is inexact work, especially when the event under scrutiny has grown to legendary status.

...whether, and to what extent, a particular military operation contributed to the accomplishment of a strategy’s objectives determines its strategic importance...

Even so, this article recommends a working definition for this task: whether, and to what extent, a particular military operation contributed to the accomplishment of a strategy’s objectives determines its strategic importance. Using this definition, this article will explore the strategic importance of the Doolittle Raid from the American, Japanese, and Chinese perspectives. Exploration of this military operation and the strategies at play, reveals that Doolittle’s Raid had virtually no impact on the realization of American or Japanese strategies. However, the planning and aftermath of the raid appears to have had a significant impact on China’s strategic outlook.

America’s Strategic Reality

“[O]ur people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger. With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph—so help us God.”

—President Franklin D. Roosevelt, December 8, 1941

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivers his "Day of Infamy" speech to Congress on December 8, 1941. (U.S. National Archives/Wikimedia)

President Roosevelt’s speech immediately following Pearl Harbor, signaled clearly that the nation was at war with all its enemies. Still, the U.S. was in no position to wage war on them all. As early as the summer of 1941, U.S. leaders designated Europe as the decisive theater and devised their military strategy accordingly.[8] War Department plans emphasized a strategic offensive to defeat Germany, while maintaining a strategic defensive posture in the Pacific until conditions supported defeating the Japanese.

Furthermore, from late 1941 to early 1942 the U.S. faced daunting circumstances that constrained offensive options in the Pacific. American naval and land forces were far behind their adversaries in armaments, with major land forces untrained and still in development. By 1942, U.S. rearmament was well underway, but the Navy’s eight battleships, twelve carriers, and three thousand airplanes would not be ready for war until late 1942 or early 1943.[9] Prior to the war, Army maneuvers in New York in August of 1940 gave President Roosevelt a glimpse of the poor state of American ground forces, which substituted drain pipes for machine guns and cars for tanks.[10] Through intensive rearmament, mobilization, reorganization, and training which ran from 1940 to 1943, the Army made steady improvements, but it was not prepared for a Pacific offensive.

Pearl Harbor was but one of several Japanese military objectives in the Pacific.[11] In late 1941, Japan seized the initiative and retained momentum with subsequent attacks in the Philippines and the East Indies, acquiring indispensable seaports and potential airfields. Contrary to common belief, the April 1942 raid did not compel the Japanese to seek decisive battle at Midway Island to protect their homeland. By February of 1942 Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had already set his sights on Midway and its strategic airfield, threatening to rob the U.S. of its unsinkable aircraft carrier and complete the destruction of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.[12]

Insufficient war materiel was another sobering concern. Mobilizing for Europe and satisfying the insatiable demands of the Lend Lease Program left the U.S. with few resources to counter Japan’s Kidō Butai (the First Air Fleet or the Mobile Force)—six large aircraft carriers and associated battleships, each working in concert to deliver over three times the naval air power of an American carrier.[13] In 1942, a meaningful strategic offensive against the Japanese was beyond America’s reach.

Conquering the Pacific

“The situation being such as it is our empire, for its existence and self-defense, has no other recourse but to appeal to arms and to crush every obstacle in its path.”[14]

—Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, December 8, 1941

Hideki Tojo, Prime Minister of Japan, during World War II (Wikimedia)

Japan’s leadership created what they believed would eventually become a tolerable arrangement in the Pacific: the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.[15] Japan quickly achieved its vision through fierce application of military power to seize and defend vital interests in the South Pacific. Japan’s strategy assumed the U.S. and its Allies would accept the new status quo when costs in blood and treasure to reverse Japan’s conquests ran too high. However, Japan’s ambitious plan had a blind spot in that it underestimated U.S. resolve.[16]

Conceivably, the Doolittle Raid foreshadowed rejection of Japan’s designs for the Pacific, but it neither disrupted nor deterred the Japanese.[17] For the Japanese, the raid merely presented a tactical problem to be dealt with swiftly and severely. However, the fog surrounding the raid lingered as the U.S. would not release information that might jeopardize its airmen. Their withholding of information even prompted Japan to request that the U.S. detail the raid.[18] Nevertheless, Japan felt compelled to act to save face and prevent future attacks on the homeland by ruthlessly eradicating any threat of future raids emanating from Chinese airfields. Army commanders knew Chinese airfields within bomber range represented a threat to the homeland. In late April, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters issued orders to the Thirteenth Army, along with elements of the Eleventh Army and the North China Army. Acting on limited information, the focus of their efforts and fury naturally became the American airmen, their Chinese abettors, and any potential Chinese airfield within range.[19]

China’s Dilemma

“I have always told my subordinates that when they commit any mistakes, the blame must be laid on the superior officers.”

—Chiang Kai-shek

Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek fully grasped the strategic importance of Doolittle’s Raid with respect to his strategy to win control of China. The raid presented a strategic opportunity to posture for the eventual fight against Chinese Communists once World War II ended.[20] The American plan called for the airmen to complete their bomb runs, land at five eastern Chinese airfields in Chekiang and Kiangsi provinces to refuel, and then fly 800 miles further inland to the new capital at Chunking. Once there, the B-25Bs would form a new squadron to carry out strikes against the Japanese as U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had indicated in communications to Chiang.[21] However, General Marshall omitted that Tokyo was a bombing target because Chiang would likely back out rather than face Japanese retaliation.

Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek fully grasped the strategic importance of Doolittle’s Raid...

By making Chinese airfields available for the raid, Chiang Kai-shek thought China could gain greater U.S. war materiel commitments for conducting military campaigns against the Japanese, in the near term.[22] In the long term, Chiang likely believed a display of military power would galvanize Chinese confidence and support for Nationalist forces. He also understood the potential for Japanese retribution. His support to the United States was a shrewd gamble that failed to pay off.

Doolittle and flight crew in China after the April 1942 raid on Japan. (U.S. Army Air Force Photo/Wikimedia)

Backing the raid failed to stimulate U.S. support and may have cost an estimated 250,000 Chinese lives.[23] Fifty three Japanese battalions invaded the regions where Doolittle’s men parachuted from their aircraft. The Japanese army’s mission was to prevent land-based bombings on the home islands by destroying airfields, but they also made a point to punish the Chinese. Japanese soldiers remained in the village of Nancheng for up to a month “roaming the streets in loincloths much of the time, drunk a good part of the time, and always on the lookout for women.”[24] Soldiers methodically torched every village, killed livestock, wiped out entire families, kidnapped young boys, and stripped out every usable resource to repurpose it for the war efforts. Those Chinese who directly aided the American airmen faced some of the most inhumane treatment. Japanese soldiers soaked one Chinese man in kerosene then forced his wife to set him ablaze. Additionally, Japan’s Unit 731, a clandestine outfit, was charged with carrying out bacteriological warfare against Chinese villagers returning to their homes after Japanese occupation ended. Unit 731 contaminated water supplies with paratyphoid and anthrax. They also fed typhoid and paratyphoid contaminated rolls to starving Chinese prisoners.[25]

Ironically, Japan’s brutal response may have strengthened the tenuous partnership between Nationalists and Communists forces whose common goal was getting the occupiers out of China.[26] Still, the U.S. remained focused on Europe, while China’s liberation waited.

Conclusion

While Doolittle’s Raid meant very little for American and Japanese strategic plans, it held wider significance for the Chinese. For America, the raid enacted revenge for Pearl Harbor and lifted the national mood, but it had no bearing on the Europe first strategy. In Japan, the raid created a brief flurry of action to eliminate the threat of land-based bombing attacks, which proved largely fruitless because the raid emanated from the sea. As promised, China received and supported the Doolittle Raiders, yet Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces did not receive any aircraft or other materiel support. The Chinese people ultimately paid a high price in blood for the strategic miscalculation of their leaders. To their credit, the brave men who undertook this dangerous operation faithfully carried out Roosevelt’s revenge strike in spectacular fashion. Seven raiders lost their lives during this mission, with some facing horrific conditions in Japanese captivity. Doolittle’s Raiders are indeed legendary, but their strategic importance is another question.

Chris Byrd is a U.S. Army officer and graduate of the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Painting of a B-25 taking off from an aircraft carrier. (Doolittle Raider Art Network)

Notes:

[1] Craig L. Symonds, The Battle of Midway (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 43. In the weeks and months after Pearl Harbor, Japan seized Thailand, Hong Kong, Manila, and Singapore.

[2] Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid that Avenged Pearl Harbor. p 25-27. Following Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt knew that public anger would eventually fade and shift to criticism of the government and the military for lapses that led to the Japanese attack. He sought to use the initial emotions following the raid to keep the public focused and to motivate the country for war.

[3] Andrew P. Stohlmann, “The Doolittle Raid In History and Memory,” (Master’s thesis, University of Nebraska, 1999), 1-10. Andrew Stohlmann argues that the Doolittle Raid attained legendary status during a three stage process. This process replaced the objective truth with multiple, specific mythical versions of the events. These mythical versions served the specific values and needs of different segments of society. At the time, America needed a heroic story with a dashing hero to boost flagging morale.

[4] Symonds, The Battle of Midway, 131. The American pilots hit an oil tank farm, a steel mill, and slightly damaged Japanese carrier Ryuho while it was in the shipyard undergoing conversion.

[5] Bruscino, Tom. "'Bomb Japan! Bomb Japan!': The Aftermath of the Doolittle Raid in China". Journal of America's Military Past 30, no.1 (Winter 2004). p. 16. Had they survived, the B-25Bs were destined for the China-Burma-India Command, which was under Chiang’s command. The Russians interred one plane and its crew in Vladivostok.

[6] Colin S. Gray, Modern Strategy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 17

[7] U.S. Department of Defense. Joint Operations. Department of Defense. JP 3-0. Washington, DC.: Government Printing Office, 2017, p. GL-14. Strategy is defined as: A prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives. The instruments of national power are: diplomatic, information, military and economic.

[8] Charles E. Kirkpatrick, An Unknowable Future and a Doubtful Present: Writing the Victory Plan of 1941 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army), p. 42; 63-71; 76.

[9] Symonds, Battle of Midway, 19-20. Plan Orange, the blueprint for war against Japan, called for most of the U.S. naval forces. However, the Battle for the Atlantic and Germany first took precedence over the Pacific.

[10] Scott, Target Tokyo, 27.

[11] Symonds, The Battle of Midway, 36-37. The Japanese also targeted the Dutch East Indies, British Malaya, and the Philippines.

[12] Ibid, 102. In the summer of 1941, the U.S. Navy converted Midway into a sheltered anchorage for seaplanes and submarines. The Island allowed the U.S. to patrol the Pacific from Hawaii to the Japanese shores. Admiral Yamamato calculated that threatening the island would draw the U.S. into a decisive battle that would destroy the U.S. Pacific fleet once and for all.

[13] Ibid, 25. Kido Butai literally means “Mobile Force”, but the spirit of the term is better understood as “Attack Force” or “Strike Force.” It was comprised of six large aircraft carriers and two fast battleships, screened by a dozen cruisers and destroyers. In contrast, American carriers mostly operated independently. The Kido Butai could put up to 412 planes in the air at a time, whereas an American carrier could manage only 90 or so.

[14] Emperor Hirojito, “Tojo reading Hirohito speech: Japan declares war on U.S., Britain,” United Press International, accessed 24 February 2018, https://www.upi.com/Archives/1941/12/07/Tojo-reading-Hirohito-speech-Japan-declares-war-on-US-Britain/5103382818544/.

[15] Symonds, The Battle of Midway, 24.

[16] Scott, Target Tokyo, 131 and Symonds, The Battle of Midway, 179. Admiral Yamamoto was very concerned about the U.S. fighting spirit and their ability to rebound from Pearl Harbor and re-generate its Pacific fleet.

[17] Ibid, 134. Japan recognized that the US would not lay down and accept the new status quo. The string of U.S. attacks in February 1942 against Wake, Marcus Islands, New Guinea, etc. were a constant reminder that decisive battle with the U.S. Pacific was required to ensure Japanese victory.

[18] Stohlman, p. 24-25.

[19] Scott, Target Tokyo, 375.

[20] Ibid, 104.

[21] Ibid, 106. General Marshall charged Lieutenant General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, Chiang’s recently appointed Chief of Staff, to ensure the Chinese followed through with logistical preparations such as securing the airfields and providing fuel for the B-25Bs and crews. Marshall held out the bombers as an incentive for Chiang’s support but he also did not inform Stilwell that Tokyo was targeted.

[22] Bruscino, ‘Bomb Japan!’, 13. As early as December of 1940, Chiang had offered up Chinese airfields for use by American and British aircraft.

[23] Scott, Target Tokyo, xx. Scott used DePaul University archives which contained firsthand accounts from American and Canadian missionaries serving in Cheikang and Kiangsi provinces. Still, it is hard to say for certain how many Chinese perished in the raid’s aftermath.

[24] Ibid, 382-385.

[25] Ibid, 388. Commanded by Japanese Army General Ishii Shiro, Unit 731 conducted numerous experiments on live human subjects to develop and perfect biological warfare weapons and delivery techniques.

[26] Bruscino, ‘Bomb Japan!’, 13