The United States faces a host of innovative threats to its military challenging the uninhibited global access it has enjoyed as the dominant superpower. From advanced bases in the South China Sea to anti-carrier cruise missiles, the U.S. military’s presence and unimpeded access to many parts of the world is becoming more constrained. While the U.S. has continually maintained a sizeable margin in military technological superiority over many adversaries, recent developments from near-peer competitors such as China and Russia are beginning to challenge this supremacy. The 1973 Arab-Israeli War provides an example of how even relatively inferior forces overcame similar threats from a more powerful adversary through a whole of government approach. Moreover, in an age of increasing emphasis on technological supremacy in warfare, Operation BADR proved that leveraging all elements of national power in crafting operations can yield an equally effective path to victory absent superior technology. There are, perhaps, lessons here for the U.S. and others.

Operation BADR

A trench and bunker of the Israeli Bar Lev Line, from Military Battles on the Egyptian Front by Gammal Hammad. (Wikimedia)

Operation BADR was the combined Egyptian and Syrian military campaign against Israel during the opening stages of the October War of 1973. This military operation would become the fourth war Israel would fight against its Arab neighbors since 1948. To prevent Egypt from establishing a foothold on the Sinai Peninsula, Israel constructed a perimeter comprised of steep sand embankments interspersed with defensive strongholds that stretched from the Gulf of Suez to the Mediterranean Sea: the Bar Lev Line.[1] Faced with this seemingly unassailable anti-access/area denial (A2AD) obstacle, Egyptian military leaders would require not only ingenuity to overcome it, but a cohesive strategy that also denied Israel the initiative it had in previous wars.

Content with its more advanced military apparatus, new territorial gains, and further political backing from U.S. military technology and economic aid, Israel stood at a position of advantage over surrounding nations. After a decisive victory over Arab aggressors in the 1967 Six Day War, Israel concluded it was superior both militarily and economically, the Arab states were not capable of a “joint political and military action,” and “Israel enjoyed the sympathy of most of the world in its ‘involuntary’ struggle against Arabs.”[2] Supported by robust intelligence and defense organizations, Israel concluded its Arab neighbors were unprepared for war and warned them Israel would quickly defeat any attempt at Arab belligerency.[3] Egyptian President Anwar Sadat would use Israeli hubris against it while creating the conditions necessary to achieve operational and strategic surprise to defeat a seemingly impregnable defense.

All DIME, All the Time

Operation BADR bears the hallmarks of an operation designed to employ all diplomatic, informational, military, and economic (DIME) components of national power to achieve a country’s strategic objectives. Though Egypt’s military lacked the sophistication and superior technology of the Israeli military, Sadat conceived of an operation that would put Israel on the horns of a dilemma by using all elements of his nation’s power. With the assistance of other Arab countries in the form of economic aid, oil embargos, and shipments of the latest Soviet technology, Egypt would leverage every aspect of DIME to set the conditions for a surprise attack against Israel. Subsequently, the Egyptian and Syrian militaries would then conduct a simultaneous attack on Israel from two separate geographic fronts to overwhelm Israeli defenses.

To capitalize on their initial surprise, Egypt and Syria needed to synchronize their operations across all the elements of diplomacy, information, military, and economy while also denying Israel the opportunity for preparations it needed for its military to function. To achieve this, Egypt leveraged the full spectrum of information operations across its campaign. For instance, Egypt and Syria used deception and practiced disciplined operational security (OPSEC) to their advantage.[4] Ensuring diplomats carried out normal schedules, advertising untimely ship maintenance, and demonstrating apparent equipment inadequacies while carrying out a seemingly regular Ramadan holiday schedule, for example, the elaborate Egyptian deception plan provided the appearance of country unprepared to embark on a military campaign.[5] Further supported by regular Egyptian and Syrian exercises close to its borders, Israel eventually learned to ignore large military demonstrations by its neighbors due to the high cost and general disruption associated with mobilizing reserves for multiple false alarms.[6] Egyptian operations security was so stringent that platoon commanders were only given a six hour notice before the time of attack.[7] Israel, meanwhile, did not know the war was coming until 0430 the morning of the attacks.[8] To the chagrin of Israel, the late September build-up of Egyptian and Syrian forces was largely ignored. Thus, information operations that supported Operation BADR cognitively primed Israeli intelligence services to accept a status-quo assessment contrary to the realities on the ground and the stark warnings from the U.S. State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency.[9] The Sadat government and his military generals were able use the information domain to help foster the operational initiative and exploit the element of surprise.

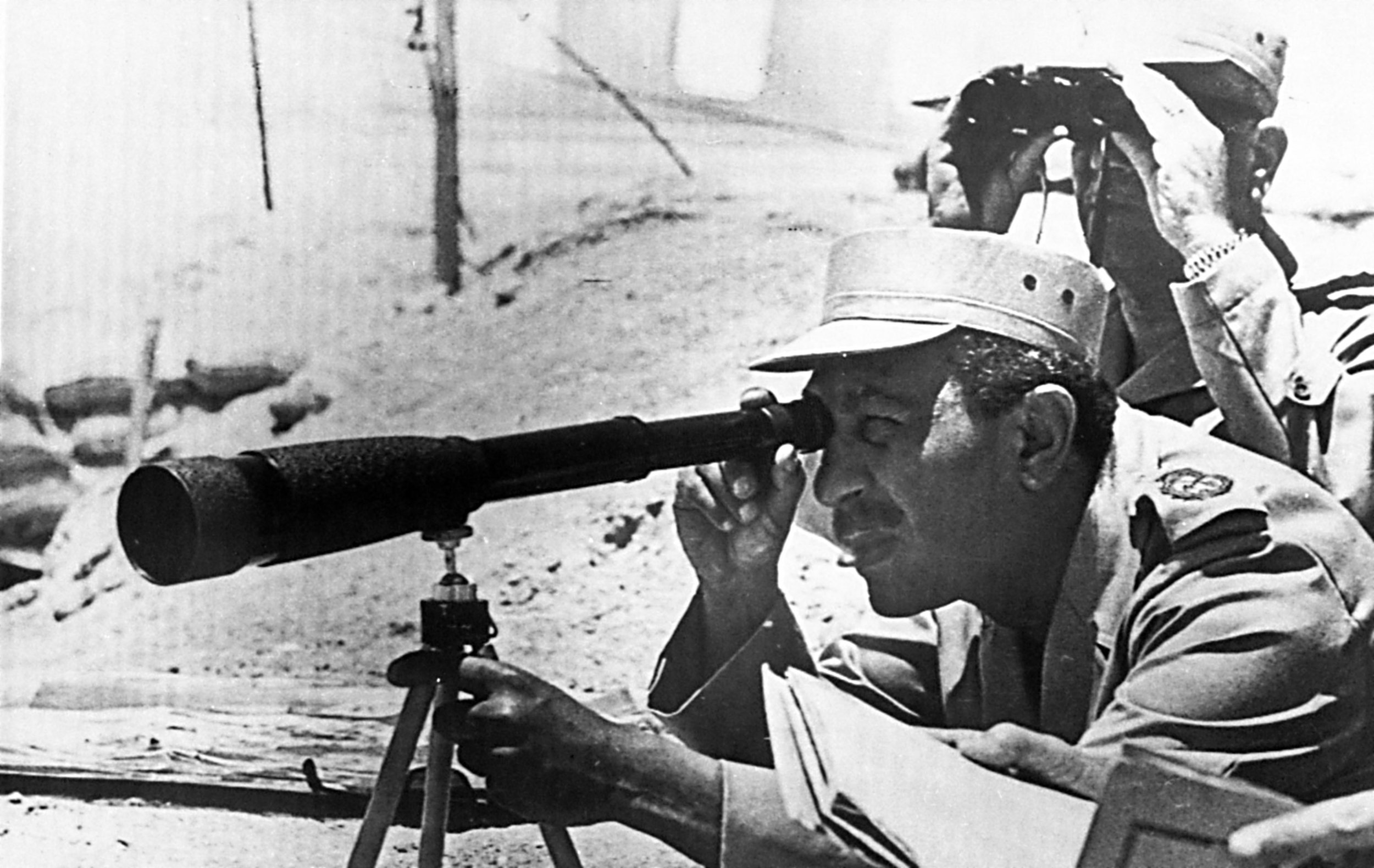

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat flanked by senior military officers during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. (AP)

While Israel would turn the tide of the war in their favor with the timely arrival of the latest U.S. armaments, superpower diplomacy, and the overwhelming force of the full Israeli military, Operation BADR cannot be viewed as failure. Egypt’s strategic objective was not to defeat the Israeli Defense Force. Instead, Sadat would state, “Diplomacy, rather than waging war, would constitute Egypt’s main effort.”[10] Waging war was only a means to re-start the diplomatic process by breaking through the intransigent attitudes of Israel’s leadership and the two superpowers.[11] Sadat knew he could not decisively defeat Israel in a full-scale war; he therefore designed an operation to gain only what was necessary to achieve his objectives—and he succeeded.[12] For instance, Sadat was asked to press his military gains by cutting off the important passes further to the east on the Sinai; however, he was more concerned about the political ends than a quick expansion of military actions to achieve it.[13] Regrettably, due to Syria’s poor military performance and Israel’s significant focus on regaining the preeminent terrain of the Golan Heights, Sadat reluctantly acquiesced to Syrian President Hafez al-Assad’s plea to take pressure off the Syrian front.[14] The result of this ill-advised attack beyond their effective operational and tactical reach was destruction of significant Egyptian combat power and the employment of its operational reserve; it was a disaster that eventually turned the initiative in Israel’s favor.[15] Nevertheless, Egypt was able to sustain the withering retribution of the Israeli Defense Force, as it held on to the east bank of the Suez just long enough for a United Nations brokered ceasefire with Israel, thus regaining the east bank of the Suez canal and restoring the morale of the Egyptian people and military.

Politics With the Addition of Other Means

True to Clausewitz’s dictum that “war is nothing but the continuation of policy with other means,”[16] Operation BADR became a viable means for Egypt to attain its political objective. Egypt’s operational approach in Operation BADR integrated the numerous tactical actions needed to attain its limited military objectives into a cohesive effort that achieved Sadat’s original endstate of regaining the use of the Suez Canal. Further, Operation BADR restored Arab military morale and ended their reliance on a more attritional form of warfare. More importantly, Egypt was able to directly link short-lived military successes to strategic outcomes that ultimately led to a desired political aim while also reinvigorating Arab morale throughout the region. Sadat achieved this through balancing ends, ways, and means, while also managing significant risks. While this gamble could have resulted in the complete destruction of the Egyptian army, Sadat’s calculated risks throughout the operation made up for what he lacked in ways and means. In some cases, a strategic victory may entail calculated tactical and operational losses, especially when such events can play to one’s favor on the world stage. As a result, Operation BADR provides valuable lessons for military planners’ incorporation of diplomatic, informational, military, and economic tools across all elements of operations for achieving political ends.

A knocked out Israeli M60 tank amongst the debris of other armor after an Israeli counterattack, from Military Battles on the Egyptian Front by Gammal Hammad (Wikimedia)

Conclusion

Because much treasure is spent on technological solutions to counter anti-access and area-denial strategies, it is easy to miss the forest for the trees in the strategic approach to operations. Developing alliances with surrounding nations in close proximity to an adversary could equally, and potentially at a lower cost, negate an adversary’s capabilities. Egyptian and Syrian efforts during Operation BADR demonstrate how a joint-combined operation diluted the Israeli response and essentially nullified an obstacle. All threats are not equal, to be sure, whether due to geography or the use of a variety of distinctive technologies. Therefore, developing technologies to defeat common denial scenarios can become an exercise in never-ending technological brinkmanship. Most importantly, U.S. military and government planners at the highest levels should eschew strictly military-centric options and demand a systems-based approach that fosters cooperation of all instruments of national power to achieve victory. Preparing for threats through a true integration of all elements of the so-called DIME will provide national leaders the full palette of possibilities necessary to solve their nation’s most intractable problems and achieve its objectives.

Scott A. Humr is a United States Marine and a recent graduate of the Marine Corps’ Command and Staff College. The views expressed are the author’s alone and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat during a visit to the Sinai Peninsula before the October war. (AP)

Notes:

[1] Simon Dunstan, The Yom Kippur War 1973 (2): The Sinai, (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012), 9-10.

[2] Frank Aker, October 1973 The Arab Israeli War, (Archon Books, Connecticut 1985), 5.

[3] Edgar O'Ballance, No Victor, No Vanquished. San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, (1978), 50.

[4] George W. Gawrych, The 1973 Arab–Israeli War: The Albatross of Decisive Victory (1973), 25-25.

[5] David T. Buckwalter, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Case Studies in Policy Making and Process, (2012), 122.

[6] Ibid., 122.

[7] Gawrych, 24.

[8] Buckwalter, 121.

[9] Ibid., 123.

[10] Gawrych, 13.

[11] Ibid., 12.

[12] Ibid., 12.

[13] Ibid., 53.

[14] Jerry Asher and Eric Hammel, Duel for the Golan: the 100-hour battle that saved Israel (Pacifica Military History: 1987), 260; Gawrych, 55-56.

[15] Gawrych, 56-57.

[16] Carl von Clausewitz, On War. edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton University Press: New Jersey, 1976), 69.