Hadji Murad. Leo Tolstoy. New York, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2006.

Coming to grips with the memories and lessons of America’s long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is a task that will occupy those who fought them, and who still fight them, for many years. That ongoing struggle is especially complicated for those whose responsibilities gave them a perspective into the strategic decisions that determined the courses of those wars. The histories of these conflicts and of relevant predecessors will predominate in any thinking about them, but their counterparts in fiction can also convey the subjective and personal aspects of the experience of war in ways that history cannot.

An illustration of Hadji Murad

For a fictional precursor to these contemporary conflicts, it would be difficult to do better than Leo Tolstoy’s short novel Hadji Murad, which tells the story of the thirty-year war between Russians and Muslim holy warriors in the Caucasus in 1829-59, a precursor to the recent war in Chechnya and the long wars against the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State. Hadji Murad, written in the final years of Tolstoy’s life and published posthumously in 1912, encapsulates an understanding of the behavior of people in wartime that Tolstoy presented in War and Peace in the 1860s and developed further over the rest of his life.

A proper understanding of Tolstoy is essential if one is to understand the story presented in Hadji Murad. Remembered as an author of lengthy novels and as the long-bearded pacifist he became late in his life, Tolstoy was born into one of the highest aristocratic families in Russia. As a young man, he spent much of the 1850s as an army officer in several military campaigns. He saw front-line service in the Caucasus and in the siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War, service that inspired one of his first published works, the Sevastopol Sketches. His father was a veteran of the 1812 resistance against Napoleon’s invasion, and both sides of his family included leading generals in that war, several of whom he adapted into characters in War and Peace (1869).[1] He saw the face of battle and the complexity of a war against Muslim insurgents, and from his earliest years knew the political complications of war from his family history in Russia’s elite class. This wealth of experience informed his portrayals of men and women at war, portrayals that reached their final form in Hadji Murad.

Colonel Sean MacFarland and Captain Travis Patriquin of the 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division with Sheikh Sattar Abu Risha in Ramadi, October 2006

Hadji Murad tells a story from Tolstoy’s first military campaign. He joined the Russian army in 1851 and went to the Caucasus in 1851-52. There, the real-life historical figure Hadji Murad, a Muslim tribal leader, held the entire campaign in the balance. Tolstoy completed Hadji Murad over half a century later, having learned countless lessons about life, war, and the events he had witnessed at the age of 23.

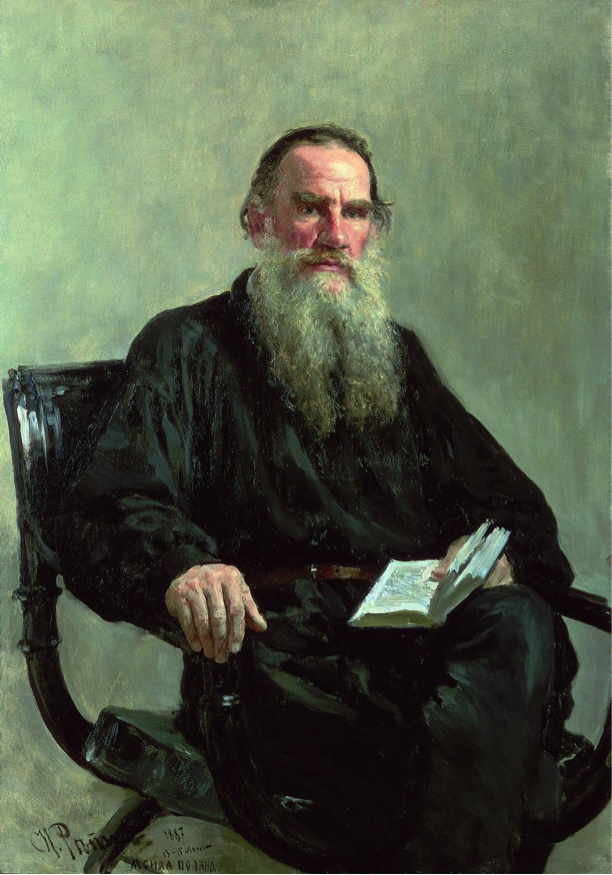

An 1887 portrait of Tolstoy by Ilya Repin, one of the definitive images of Tolstoy

Hadji Murad presents a situation Americans will find uncomfortably familiar in many ways. The Russians were well into their second decade of war against the charismatic Muslim leader Shamil and his followers, the murids, precursors to the jihadists of today. Fatigue with the long war had set in, with Tsar Nicholas I and elite society in the distant capital paying little attention. An unexpected breakthrough occurred when tribal leader Hadji Murad, an ally of Shamil and the Russians’ fiercest opponent, had a falling out with Shamil and changed allegiance. He offered to lead his people against Shamil and his murids, partly to defeat Shamil and partly to save his family whom Shamil was holding as hostages. Russian military commanders, despite years of facing Hadji Murad in battle, knew his defection could change the course of the war. They went to great lengths to earn his trust and passed his plan to the war minister and the Tsar, expecting it to be approved and for victory to follow soon.

The efforts of the officers in the field were for naught, however, as their distant civilian leaders ignored them and substituted their own ideas. The war minister, who harbored an old resentment of his front-line general, disliked the plan to use Hadji Murad and intentionally misrepresented it to the Tsar as being soft on the enemy. With no thought about the situation at the front or Hadji Murad other than how his capture would make the enhance the appearance of his leadership, the Tsar casually approved the minister’s plan for a scorched earth campaign. The troops in the field and the actual war they were fighting were of little concern as the personal concerns of political leaders in the capital dictated the course of the war.

The events set in motion by these orders changed the course of the far-away war and destroyed the lives of countless people on both sides, including Hadji Murad, killed while trying to escape and rescue his family. Newly arrived troops took Hadji Murad’s severed head as a trophy, horrifying the Russian veterans who had known him, had learned to respect him, and who knew everything could have been different.

Captain Travis Patriquin on the Euphrates River near Ramadi

American servicemen and servicewomen have lived out their own versions of the fictional events in Hadji Murad during the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. One such episode was the Sunni Awakening a decade ago, which began as an initiative of Captain Travis Patriquin and the 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division in Ramadi, commanded by Colonel Sean MacFarland. In Ramadi in late 2006, at a crucial juncture in the war, Captain Patriquin and Colonel MacFarland reached out to Sheikh Sattar of the Abu Risha tribe and figured out how to make him an ally in the war against the Al Qaeda insurgency in Iraq.[2] Their actions changed the terms of the fight and started to turn the tide against the insurgency. The ensuing Awakening that turned the Sunni tribes of Iraq against Al Qaeda, along with a new counterinsurgency strategy and the surge of additional U.S. forces, dealt a severe blow to Al Qaeda in Iraq that created a window of hope that a stabilized Iraq would be possible.

The success of the U.S. military in the field would come with a heavy price, however. On December 6, 2006, before the end of the battle for Ramadi, a roadside bomb killed Travis Patriquin along with U.S. Marine Major Megan McClung and Specialist Vincent Pomante III. Al Qaeda assassinated Sheikh Sattar in September 2007, robbing the Sunni Awakening of its charismatic leader. Ultimately the entire Sunni Awakening would be squandered, despite the efforts of the U.S. military to sustain it, rejected by the Shia-dominated government of Iraq under Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and with little opposition from U.S. civilian leaders who had decided to exit the war in Iraq and back Maliki. The Maliki government’s sectarianism and rejection of the Sunni Awakening would open the door for the rise of the Islamic State and its conquest of most of the predominantly Sunni Arab areas of Iraq in 2014.[3]

Sheikh Sattar meeting President Bush in September 2007, 10 days before his assassination

As fiction intended to elucidate moral lessons, set in a very different war a century and a half ago, Hadji Murad is an imperfect example for how to describe the Sunni Awakening and other recent events. At the same time, it reminds the reader of timeless truths about the nature of war. Like the better known (and mush longer) War and Peace, Hadji Murad shows how from the front line to the capital, wars are fought and commanded by people subject to the vagaries of human nature. These are people who may follow their political concerns, personal biases, or outright selfish needs. The influence of these aspects of human nature is always present, but how they affect strategic decisions does not often appear in the records or official histories. While the fecklessness of Tolstoy’s fictionalized Tsar Nicholas I and war minister far exceeds anything seen in the U.S. government in 2001-16, most of the foibles described by Tolstoy have existed, in different forms, in many who have made decisions affecting America’s long wars.

As of the start of 2018, little has been published about this aspect of the wars, aside from recriminations between politicians and salacious media coverage of retired generals, and it is possible this will never change. During the American Civil War, Walt Whitman wrote, “The real war will never get in the books,” and others have repeated it about wars that followed. There are many who were in Iraq or Afghanistan and know the harsh realities of those wars, however, so it is possible that more about them will be presented to the public eventually. If it ever happens, Tolstoy’s Hadji Murad deserves a place as a key precursor to such a look at the wars of our time.

Robert Kim is a lawyer who worked for the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of the Treasury, including serving as Deputy Treasury Attaché in Iraq in 2009-10. His position made him a participant in the demise of the Sunni Awakening and many other events during the withdrawal of the U.S. military presence in Iraq.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header image: Picture from the 1981 edition of Leo Tolstoy’s ‘Hadji-Murat’ | I. Urmanche

Notes:

[1] An authoritative biography of Tolstoy is Life of Tolstoy by Aylmer Maude, Tolstoy’s friend and English translator who received his permission to be his biographer, but at over 1,000 pages, it is as long as a Tolstoy novel. A more recent and accessible biography is A.N. Wilson, Tolstoy: A Biography, W.W. Norton & Company, 2001.

[2] For the full story of these actions, see William Doyle, A Soldier’s Dream: Captain Travis Patriquin and the Awakening of Iraq, NAL Caliber, 2011; Chad M. Pillai, “A Tribute to Captain Travis Patriquin,” Small Wars Journal (December 10, 2010); http://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/a-tribute-to-captain-travis-patriquin; Major Niel Smith and Colonel Sean MacFarland, “Anbar Awakens: The Tipping Point,” Military Review, March-April 2008, http://usacac.army.mil/CAC2/MilitaryReview/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20080430_art008.pdf.

[3] For insider accounts of high-level U.S. decisions during this period, see Ali Khedery, “Why We Stuck With Maliki – And Lost Iraq,” The Washington Post, July 3, 2014 https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-we-stuck-with-maliki--and-lost-iraq/2014/07/03/0dd6a8a4-f7ec-11e3-a606-946fd632f9f1_story.html?utm_term=.18cdfe572979; Emma Sky, The Unraveling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq, Atlantic Books, 2015.