War Porn. Roy Scranton. New York, NY: Soho Press, 2016.

“Look, the photographs say, this is what it’s like. This is what war does. And that, that is what it does, too. War tears, rends. War rips open, eviscerates. War scorches. War dismembers. War ruins.”

—Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others

War Porn avulses beauty. Roy Scranton’s novel cuts deep into the romantic image of war, eviscerating the heroic ideal. War’s innards spill out, the blood pooling amongst the words, the warmth attenuating towards death. Like Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, War Porn infuses powerful, beautiful, hallucinatory language into a distressing, gritty, noxious reality.

Not that you should expect anything less from a book titled War Porn.

Like any work of art, it requires multiple viewings—pausing, rewinding, and even fast-forwarding—to begin to appreciate the layered and complex depiction of war and its commodification presented by Scranton:

We’d prepared our whole lives for this. Bombed little brown people, helicopters swooping low, the familiar sigh of American machinery carving death from a Third World wasteland. We expected nothing less than shell shock and trauma, we lusted for thousand-yard stares—lifelong connoisseurs of hallucinatory violence, we already knew everything, felt everything. We saw it through a blood-spattered lens, handheld tracking shot pitting figure against ground. We were the camera, we were the audience, we were the actors and film and screen: cowboys and killer angels, the lost patrol, the cavalry charge, America’s proud and bloody soldier boys.[1]

Every word in War Porn feels mulled over, considered, and then etched into the story’s soul. Linking the narrative is a commentary on Americans’ fetish for war as consumers and “lifelong connoisseurs of hallucinatory violence.” The “blood-splattered lens” is just the next iteration in the evolution of the mediated wartime experience.

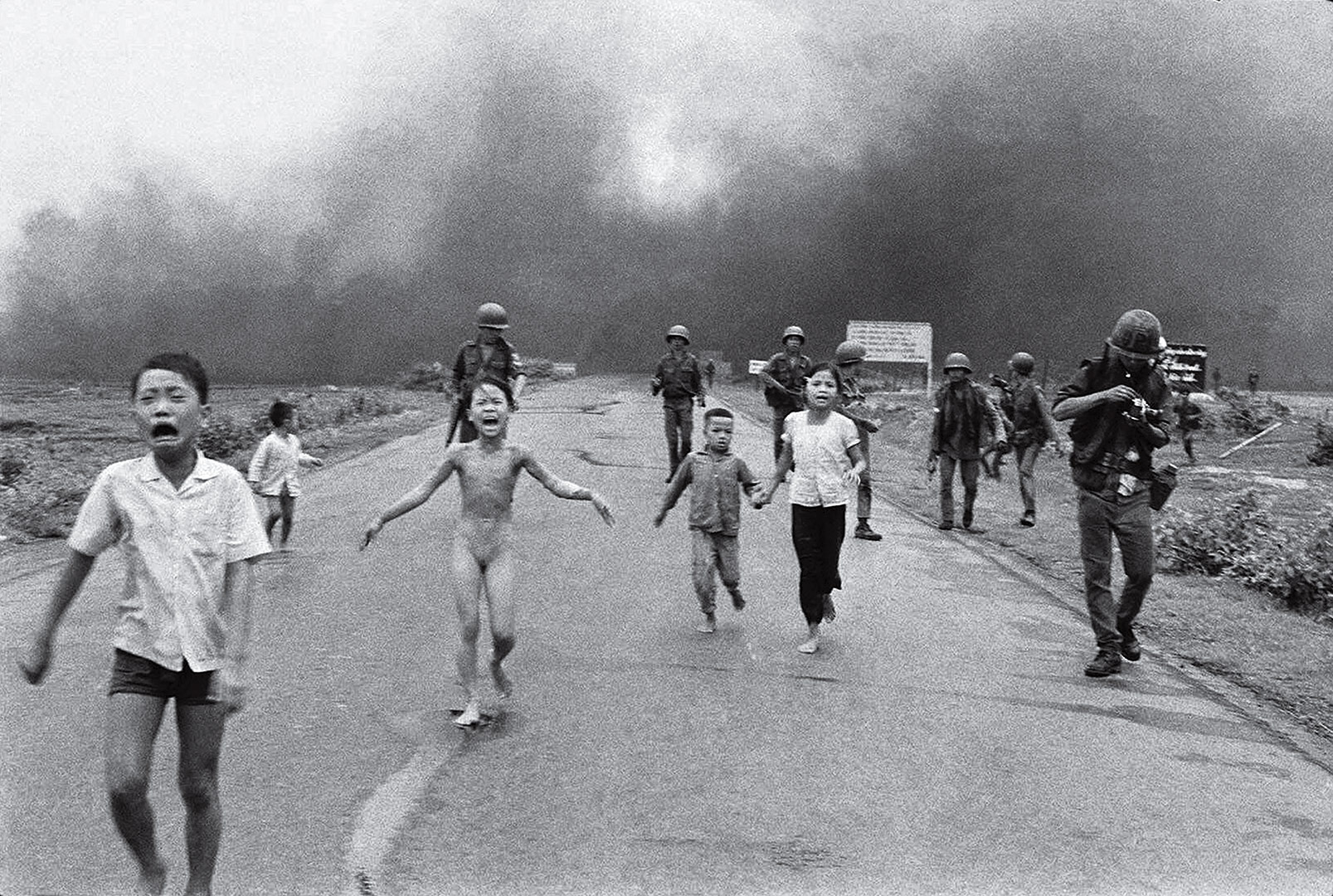

Susan Sontag, in Regarding the Pain of Others, explains, “The ultra-familiar, ultra-celebrated image—of an agony, of ruin—is an unavoidable feature of our camera-mediated knowledge of war.”[2] Images of war are prolific encapsulations of violent political interaction. Moreover, Sontag reminds us that “The understanding of war among people who have not experienced war is now chiefly a product of the impact of these images.”[3] Consider the images below and reflect on the violence depicted and their place within the larger strategic narrative:

But what began as a singular carnage-infused image has now manifested as broadcasts available to anyone who has the requisite IP address.[4] The appreciation of a celebrated image has now mutated into “a healthy-sized regard for watching stuff get blown up,” a trend Noah Shachtman analyzes in the Wired article “Video Fix: Dropping’ Bombs.” He continues, “Most of these [online videos of war] flicks have a bunch of elements in common: Heavy metal. Gleaming military gear. Shouts of ‘Hooah!’ or ‘Get some!’ And of course, explosions. Freakin’ ginormous explosions.” Today we can even watch live pred porn, as it is often called. Or edited-down clips, like from this tweet from @CJTFOIR, calling for “MORE STRIKES” because “#daesh can’t quite get up to 88 mph.”

This dissemination of such specific, war-themed “patterns of excess, fantasy, desire, and shame,” becomes war porn.[5] Scranton dives deep into all, the valorization as well as the squalor, and, with unflinching observations, presents a direct critique of such consumption—but not without empathy. In the structural and emotional heart of the novel, Scranton writes of an Iraqi family who can either look out their window, or watch CNN and Al-Jazeera, and see “their city in green from above, in videos made by the men who were killing them, bright neon stripes cutting the screen, pale green explosions below.”[6] Where is the war porn? On the flickering TV screen, or outside their window?

It is impossible to talk about the novel without considering its narrative structure. The outermost layer is the “babylon,” which reads as a panorama of New York's Times Square, if one were tripping on acid. The “babylon” continues intermittently throughout the work, alerting the reader to the ever-present and oppressive saturation of 24/7 media. This psychedelic overload fades into a Columbus Day backyard bar-b-q as we watch Aaron’s—“the one just came home”—redeployment. Scranton’s homecoming front is not just another battle from the civilian-military clash, but a moral scrutiny concerning the promulgation of and participation in war porn. Next, layered within this novelistic sandwich is a war story pastiche that follows Specialist Wilson in a stereotypical kill memoir: a Lone Survivor or American Sniper for the everyday grunt, the ones who see themselves as “cowboys and killer angels.” Scranton does not trivialize those works, but instead focuses on how limiting, how sensationalized that perspective is. Finally, trapped underneath the gristly excess, extravagance, and profligacy is the heart and soul of the novel: the fictional story of an Iraqi professor and his family who find themselves in the midst of the war, watching it explode inside and outside.

Yet, what we label war porn now is nothing new to war. It is a part of war. Scranton begins his novel, and “babylon,” with the jarring:

rage forth, bold here & man of war, you have no

flood documenting her lament, no legal recourse in re:

administrative decisions on the matter of

torture TV rage the

rockets red not singly but in global consensus: vanquished

by my spear, the highest levels of the Department

beginning a world with no tomorrow

such is the word of man.[7]

We’ve been thrown into the fire of the original war porn: The Iliad. Homer writes,

“Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus

and its devastation, which put pains thousandfold upon the Achaians,

hurled in their multitudes to the house of Hades strong souls

of heroes, but gave their bodies to be the delicate feasting

of dogs, of all birds, and the will of Zeus was accomplished

since that time when first there stood in division of conflict

Atreus’ son the lord of men and brilliant Achilleus.”[8]

What might seem shocking or amplified in the novel is no different than the excessive violence or fantastic heroism found in Homer. Imagine what we would have seen if Achilles wore a Go-Pro.

War Porn is an attempt to come to grips with the modern, and perhaps even the postmodern, experience of war—an experience that Achilles would still understand. Yet, what is most striking is Scranton’s incessant meditation on what it means to be “a spectator of calamities taking place in another country” which, as Sontag notes, “is a quintessential modern experience.”[9] This tension forms the brutal backbone and gritty strength of Scranton’s novel, uniting all who watch war—whether up close and personal or back at home and from afar. Scranton challenges us to see war not through neon-green tinted optics, nor by the flickering images of an unyielding news cycle, but unfiltered, without excess, fantasy, desire, or even shame. Scranton strips war bare and flays it.

Mushroom cloud above Nagasaki after atomic bombing on August 9, 1945. (Charles Levy/National Archives)

Roy Scranton is a novelist, journalist, poet, and essayist who has been published in The Nation, the The New York Times, and Rolling Stone. The Strategy Bridge appreciates Mr. Scranton taking the time to talk about war and his latest novel, War Porn.

Olivia Garard: What is war, to you? This is certainly a loaded question, but many of us in The Bridge community, we operate on a level where war is violent, political, and interactive, and we can rattle off many different definitions or nuances. But intuitively, I think we all know war is much more than that. The difference between war (or even War) operates and takes us away from the very humanity and individuality that your book centers on or around.

Roy Scranton: War is socially organized political violence. What I mean by that is that war is directed, socially authorized violence undertaken by one human collective that identifies itself as a coherent, bounded body against another such body. This seems to me to be the best working sociological definition of war, helping us to distinguish asymmetric warfare—terrorism or guerrilla war, for example—from merely criminal violence, or to distinguish a war of occupation (in which one distinct political body is fighting against one or more distinct political bodies) from peacekeeping (in which one political body is working to establish a monopoly of violence in a situation where no other political body exists).

War is always political, social, and cultural. War is a deeply human activity, and has always been an important way that humans make meaning. As such, war is often not only cultural but metaphysical. One of the more important ways that most Americans (and Westerners) think about war today is, in fact, as a metaphysical or spiritual event: a "natural," extra-political eruption of transcendental reality, or in Chris Hedges's well-known phrase, "a force that gives us meaning." The idea goes back to Hobbes, by way of Clausewitz. But war is of course no such thing: war is a thing humans do, not a "force" that happens to them.

Which is not to say that war is something humans have much control over. I tend to subscribe to a pretty weak notion of human autonomy to begin with, though, so I don't think humans have as much control as they like to think they do over lots of things, especially their own will. That's another question, but it's a question deeply connected to our ideas about war, individuality, and collective existence--and, for me, my own experience of war and military life.

War is, for me, endlessly fascinating and horrifying: there is no greater testament to human ingenuity than our genius for violence, and no greater testament to human stupidity than our enthusiasm for war.

Olivia A. Garard is an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps, an Associate Editor for The Strategy Bridge, and a member of the Military Writers Guild. The opinions expressed are hers alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: U.S. President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, along with members of the national security team, receive an update on Operation Neptune's Spear, a mission against Osama bin Laden, in one of the conference rooms of the Situation Room of the White House, May 1, 2011. They are watching live feed from drones operating over the bin Laden complex. (Pete Souza/White House)

Notes:

[1] Roy Scranton, War Porn (New York: Soho Press, Inc., 2016): 54-55

[2] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003): 24.

[3] Ibid., 21.

[4] Ibid., 20.

[5] The New Yorker, September 26, 2016 “Lights. Camera. Action. Making Sense of Modern Pornography.” 68.

[6] Scranton, 217.

[7] Scranton, 3.

[8] Homer, The Iliad, trans. Richmond Lattimore (Chicago University of Chicago Press, 2011): 75.

[9] Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 18.