Russia’s power politics, demonstrated through its nationalistic tendencies, have the biggest influence on Estonia’s national security. Russia maintains a capability to influence a quarter of Estonia’s population who speak Russian, most of whom are disenfranchised by the government and are highly susceptible to Russian coercion through modern mainstream media emanating from Moscow. Due to these circumstances, Russia is in a position to cultivate Russian nationalism and influence Russian speakers in Estonia, who can elect leaders that will return Estonia back to Russia’s sphere of influence and undermine the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. An alternative view is that Estonia’s NATO membership provides enough security to dissuade Russia from exerting its influence in Estonia. In rebuttal, I offer that Russia’s potential to leverage Estonia’s democratic process to enact laws and policies sympathetic to Russia, renders Estonia’s membership in NATO irrelevant and incapable of mitigating this threat.

Russia has a long-standing history of pursuing hegemony over its neighbors through multiple means. Small European nations like Estonia are highly susceptible to Russian dominance due to their proximity to Russia, history of belonging to the former Russian Empire, and subsequently their membership in the Soviet Union. Russia’s recent occupation of the Crimean Peninsula in Ukraine and at South Ossetia in Georgia provide examples of how the Russian military seizes control in portions of neighboring sovereign nations that belonged to the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

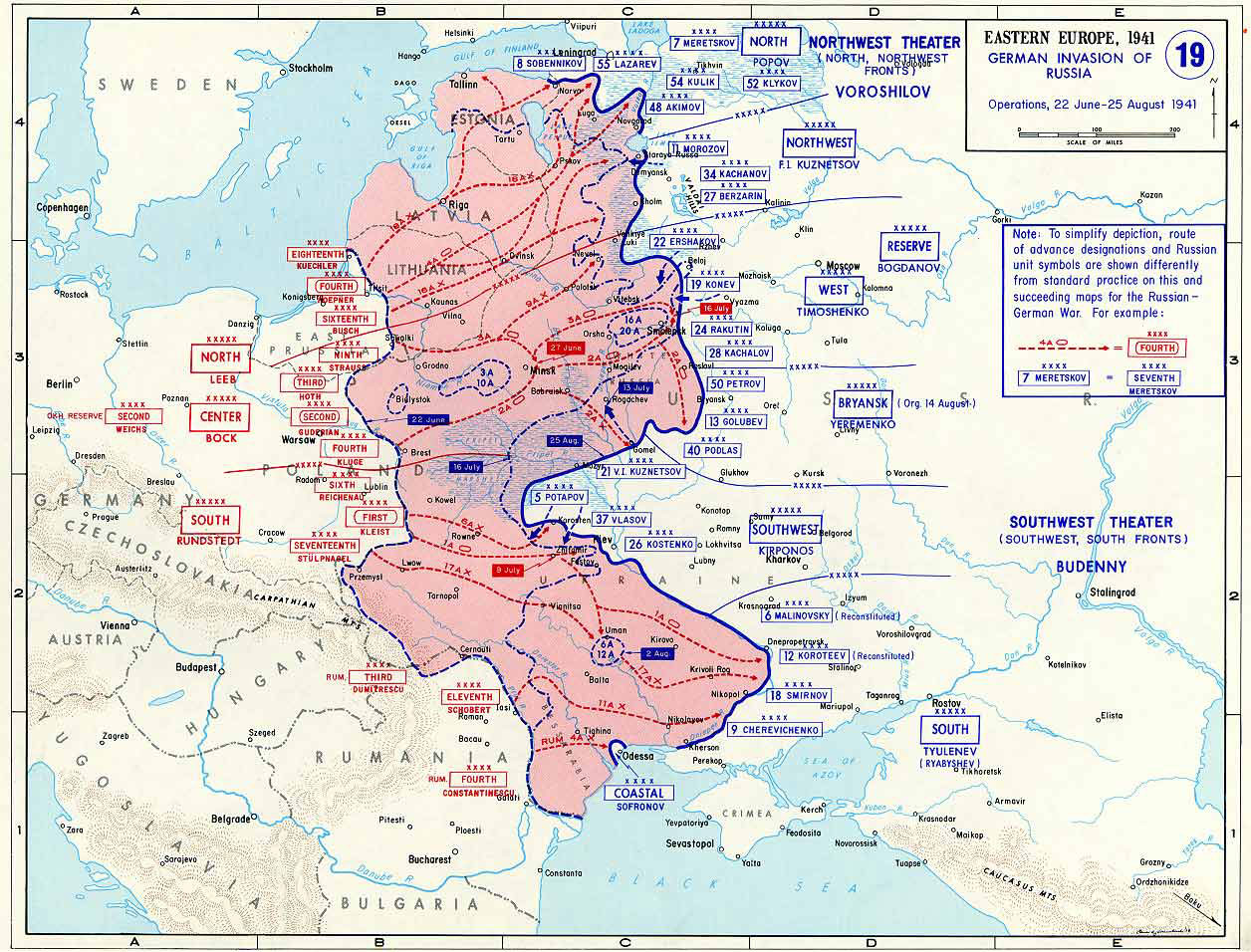

Russia’s behavior exemplifies what American political scientist John Mearsheimer describes as structural offensive realism, a school of thought that “maintains it makes good strategic sense for states to gain as much power as possible.”[1] Mearsheimer further explains that in a political system without a higher authority above the great powers, with no guarantee that one will not attack another, it makes eminently good sense for each state to be powerful enough to protect itself.” [2] Russia’s modern day philosophy of consolidating power to protect its territory stems from a surprise attack by Nazi Germany in 1941 that resulted in over four million Soviet casualties during Operation Barbarossa, and 20 million total on the Eastern front.[3] In the aftermath of these catastrophic loses, the Soviet Union created buffer space between itself and Western Europe by establishing an uncontested sphere of influence in Eastern Europe running from Estonia to Bulgaria. In the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s dissolution, NATO filled the security vacuum in Eastern Europe by adding 12 countries to its ranks, which were formally within the Soviet Union or its sphere of influence. As Russia rebuilt from Soviet era communism to a market based economy, the great power re-emerged capable of re-asserting its sphere of influence on neighboring nations. In fact, Russia once again identifies NATO as a threat to its national security as it did during the Soviet era.[4] Although NATO is an organization of 28 member states, it competes directly with Russia for security through a system of structural realism, described by MIT Political Professor Barry Posen as the “anarchical condition of international politics.”[5] Posen’s suggestion that major powers struggle to control a finite amount of security that exists in the world nests with leading international affairs professor Dr. Robert Jervis who concludes that a “security dilemma exists when a state tries to increase its security by decreasing the security of others.”[6] Dubbed the "spiral model" Jervis explains that interaction between states seeking only security strains political relations.[7] Estonia finds itself caught in the crossfire of a security struggle between Russia and NATO because Russia is attempting to reclaim dominance over its sovereign neighbors. NATO currently holds security dominance in Estonia, but according to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s former top economic adviser, Andrey Illarionov, “Putin has his eyes on eventually reclaiming Estonia”.[8]

Estonia felt the brunt of a resurgent Russia in 2007 when suspected Russian hackers overwhelmed Estonia’s Internet infrastructure in response to Estonia’s relocation of a Soviet war memorial within their capital city of Tallinn. As Estonia relocated the statue to a local cemetery, Russian sympathizers in the country rioted over the course of two days. The result was 153 injuries and 800 arrests. During the course of the unrest, the Russian government unequivocally stated that moving the statue would be “disastrous for the Estonians.”[9] Over the next several days, Estonia suffered an unprecedented cyber-attack that crippled banks, broadcasters, police, and the national government.[10] Simultaneously, during the WWII Victory Parade in Moscow’s Red Square, Putin commented “those who are trying today to desecrate memorials to war heroes are insulting their own people, sowing discord and new distrust between states and people.”[11] Moscow’s comments had the effect of fueling Russian nationalism, which manifested in the Russian speakers’ efforts to save the embroiled Soviet war memorial.

Indeed, Russia has a large and receptive audience in Estonia to influence. Russia used nationalism - defined by Posen as “a propensity of individuals to identify an interest based upon culture and shared history with a state structure to gain influence with Estonians friendly to their cause.”[12] Russian speakers in Estonia number approximately 300,000 and comprise roughly 25% of the national population. Distressingly, 2/3rds of the Russian speakers don’t speak Estonian, the national language, and feel disconnected from Estonian government. A recent Estonian government report identifies “two separate societies of Russian and non-Russian speakers living side by side with only superficial connections between them.”[13] The Russian community in Estonia is isolated because many Russian speakers have stronger links to their historic homeland in Russia than Estonia.[14] According to a study conducted by the University of Tartu, only about a third of the Russian speakers also speak Estonian and have Estonian citizenship. Another third are legally citizens of Russia. Yet, the remaining third of Russian speakers, more than 80,000 people, are stateless (neither Russian nor Estonian) but can travel freely to Russia without a visa. [15]

Russia regularly uses nationalistic propaganda through its mainstream media networks to influence Russian speakers within Estonia, many of whom have family members living in the country.

Russia regularly uses nationalistic propaganda through its mainstream media networks to influence Russian speakers within Estonia, many of whom have family members living in the country. Russian media outlets broadcast news, political commentary, and entertainment worldwide in a modern format with the objective, according to the International Center for Defense and Security to “build support among Russians for Putin and his vision of a powerful, renascent Russia.”[16] Marko Mihkelson, Chairman of the Estonian Parliament’s National Defense Committee underscores that Russia’s “sophistication using television, Internet, and social media is on the highest level.”[17] Alarmingly, in accordance to Estonian law, Russian citizens and stateless non-citizens residing in Estonia “may vote at the local government council elections if he/she resides in Estonia on the basis of a long-term residence permit or the right of permanent residence.”[18] The fact that 25% of Estonia’s population is susceptible to Russian propaganda, many of whom are disenfranchised from the national government but can legally vote, brings significant potential for Russia to easily convince voters in an Estonian election to choose the political candidates preferred by the Russian government. Consequently, multiple local level pro-Russian political leaders throughout Estonia could fan the flames of public opinion to influence national leaders to change policies and laws to be sympathetic to Russia. Considering Estonia struggled to obtain a simple majority to elect its current President in 2016, a process that took an unprecedented three separate nation-wide votes, the political will of Estonians is far from certain. Of course, the non-citizen disenfranchised Russian speakers could not vote in national elections, but the pro-Russian Centre Party achieved 25% of the national vote. If Estonia becomes sympathetic towards Russian interests in the future, the new political order is highly likely to undermine NATO’s security efforts in the Baltics.

An alternate viewpoint is that Estonia’s membership in NATO will deter Russia from interfering in Estonia’s affairs. The collective security of 28 NATO member nations codified in the Article Five of the NATO defense agreement specifies, “an armed attack against one or more signatories shall be considered an attack against them all. Moreover, member nations will take necessary action, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.”[19] The Russian occupation of Ukraine and Georgia was not stopped because neither country is a member of NATO. If Russia can tilt Estonia’s political landscape in their favor through the democratic process, the U.S. and NATO would find themselves in a difficult position to stop it. After all, the current U.S. National Security Strategy states “America is routinely expected to support peaceful democratic change.”[20] Simultaneously, the NATO Strategic Concept underscores the fact that the alliance thrives as a source of hope because it is based on, among other things, democracy.[21] Consequently, the U.S. and NATO would have little choice but to accept the will of the Estonian people.

In conclusion, Jervis’s perspective of international relations explains that Estonia’s security is based upon a larger struggle between the great power of Russia and the collective security alliance of NATO. Jervis’ spiral model predicts the security struggle between Russia and NATO will continue because Russia is attempting to reclaim its dominance over NATO in Estonia. Although Estonia will look to NATO for its security, the small European nation has a critical vulnerability expressed in its large Russian speaking population - which is highly susceptible to Russia’s mainstream propaganda. Russia has incredible potential to rally the disenfranchised Russian speakers in Estonia by using nationalism to reassert Russian security dominance in Estonia through a legitimate political process to which, ironically, the democratic countries of NATO must acquiesce.

Cody Zilhaver is a U.S. Army Colonel. He holds a B.S. from Edinboro University, a M.A. from Webster University, a M.A. from the Naval War College, and a M.A from the Air War College. The views expressed in this article are the author's and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header image: Estonian troops conduct a march past during the Opening Ceremony for Exercise STEADFAST JAZZ on the Drawsko Pomorskie Training Area, Poland | NATO Photo via USNI

Notes:

[1] John J. Mearsheimer, "Structural Realism," in Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith, eds., International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, 2nd Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 72.

[2] John J. Mearsheimer, "Structural Realism," in Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith, eds., International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, 2nd Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 72.

[3] New World Encylopedia, “Operation Barbarosa,” http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Operation_Barbarossa - cite_note-about-2, (accessed March 22, 2017).

[4] Farchy, “Putin names Nato among threats in new Russian security strategy,” Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/6e8e787e-b15f-11e5-b147-e5e5bba42e51, (accessed March 22, 2017).

[5] Barry R Posen, "Nationalism, the mass army, and military power." International Security (1993), 82.

[6] Charles L. Glaser, 1997. “The Security Dilemma Revisited.” World Politics (50): 171.

[7] Ibid.

[8] John Aravosis, “Putin wants Finland, Baltic States, says former top adviser,” http://americablog.com/2014/03/putin-wants-finland-baltic-states-says-former-top-adviser.html, (accessed March 23, 2017).

[9] Patrick H. O’Neil, “The Cyberattack that Changed the World,” The Daily Dot, https://www.dailydot.com/layer8/web-war-cyberattack-russia-estonia, (accessed March 17, 2017).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Barry R Posen, "Nationalism, the mass army, and military power." International Security (1993), 81.

[13] Kivirähk, J. 2014; “Integrating Estonia’s Russian Speaking Population: Findings of National Defence

Opinion Surveys,“ http://www.icds.ee/publications/article/integrating-estonias-russian-speaking-population-findings-of-national-defense-opinion-surveys, (accessed March 18, 2017).

[14] Katja Koort, “The Russians of Estonia: Twenty Years After,” World Affairs, July/August 2014.

[15] Jill Dougherty and Riina Kaljurand, “Estonia’s ‘Virtual Russian World’: The Influence of Russian Media on Estonia’s Russian Speakers,” International Center for Defense and Security, October 2015.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Valimised, “Right to Vote” http://www.vvk.ee/info-for-voters, (accessed March 18, 2017).

[19] “The North Atlantic Treaty,” April 4, 1949, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm.

[20] U.S. President, “National Security Strategy of the U.S.,” February 2015, 19.

[21] NATO, “Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization,” http://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/pdf/Strat_Concept_web_en.pdf, (accessed March 22, 2017)