America's War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History. Andrew J. Bacevich. New York, NY: Random House, 2016.

Thwarting this network of groups, “Most of which are local, some of which are regional, and some which are global, was going to entail a very long contest. How long? How much longer than it had already run? Wisely the general did not hazard a guess. No one had a clue.” [1]

What we now know as the Middle East was born with the Sykes-Picot Agreement in May 1916 as France and Britain divided the former Ottoman Empire into two spheres.[2] Through the years, the colonial interests of France and Britain were replaced by the United States as the former colonial powers retreated from their possessions and protectorates. Andrew J. Bacevich asked four questions regarding the actions of the United States which have induced the explosive region that we are facing today.

“First, what motivated the United States to act as it has? Second, what have the civilians responsible for formulating the policy and soldiers charged with implementing it sought to accomplish? Third, regardless of their intentions, what actually ensued? And forth, what links aims to actions to outcomes.”

Historians often find it difficult to establish a starting and ending point for a particular era. Political scientist David C. Rapoport of UCLA wrote “The Four Waves of Rebel Terror and September 11.” He argues the world is now in the “Fourth Wave” or the “Religious Wave” which emerged after the Radical Wave of the 60s and 70s ebbed and began with the Iranian Revolution.[3]

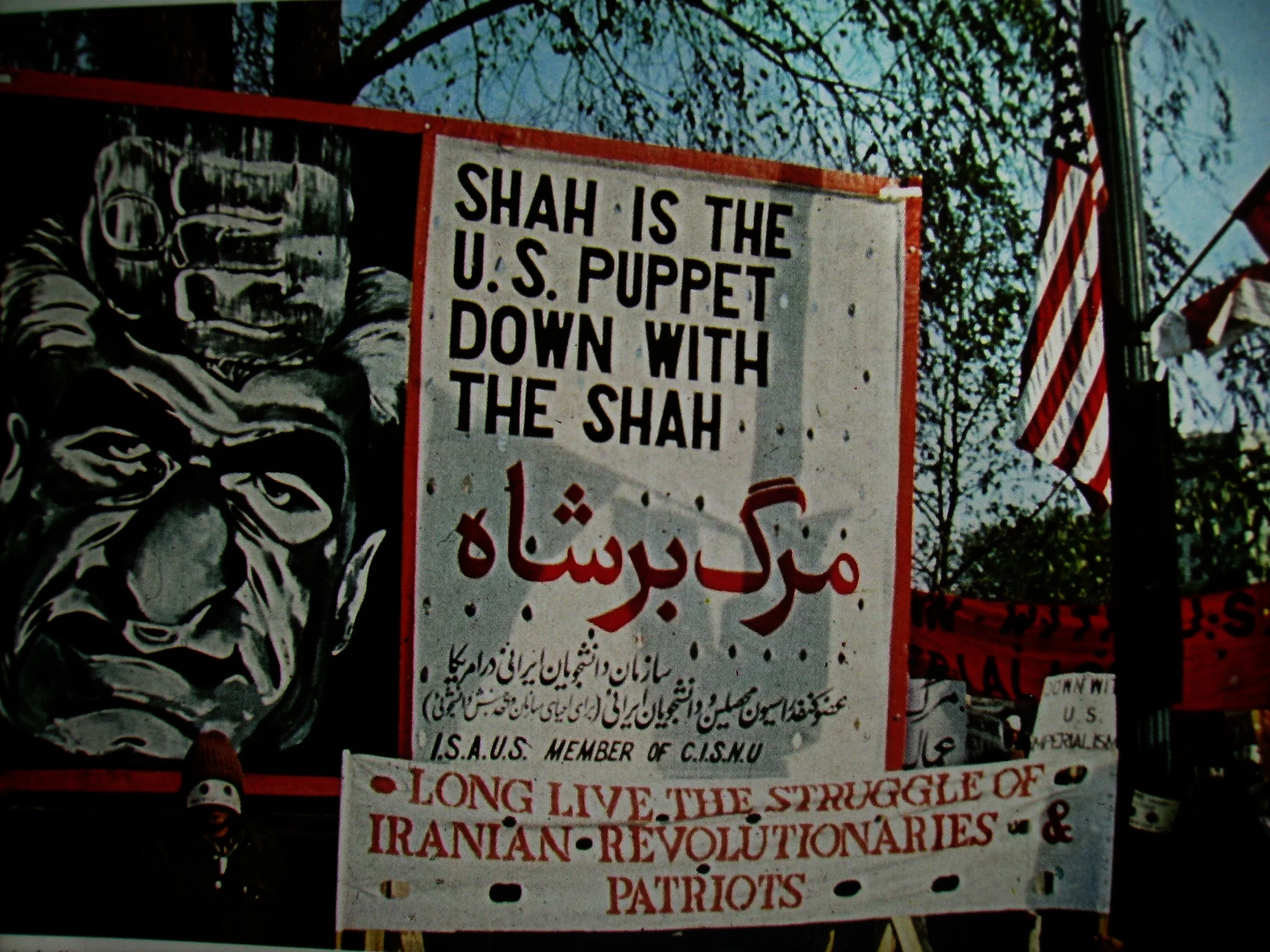

Bacevich begins America’s War for the Greater Middle East also with the Iranian Revolution and President Jimmy Carter’s decision to launch Operation Eagle Claw, the ill-fated military operation to rescue U.S. embassy personnel held hostage in Tehran. While this is a logical starting point, previous U.S. policies and military operations, dating back to the Navy and Marine Corps battles with the Barbary Coast pirates, and U.S. support for the state of Israel have affected both past and current U.S. policies as well as the world’s public opinion.

U.S. Presidents have often used the ideals of spreading democracy and protecting human rights as reasons to act in the Middle East. However, as Bacevich illustrates and historical precedent seem to support, the U.S. has more often supported “repressive dictators” than democratically elected heads of state. Bacevich offers that oil overrides any perception that the U.S. acted on any political or humanitarian idealism, and instead has acted to “preserve the American way of life.”

Bacevich illustrates America’s way of life by telling a personal story of how, as a recent West Point graduate, he drove a gas guzzling muscle car which depended on Middle East oil. He argues America’s dependence on oil has “become a weapon, wielded by foreigners intent on harming Americans.”

Bacevich relates a story that is often told to illustrate the failure of U.S. policy in the Middle East. At a state dinner in Tehran, Carter toasted the Shah of Iran as “an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world…This is a great tribute to you, Your Majesty, and your leadership and respect, and the admiration and love which your people give to you.”

Unfortunately, young college students and religious leaders were voicing their opposition to the Shah and a revolution was brewing on the streets of Tehran. Carter was elected after the nation had suffered through the Watergate years, and came into office to “un-Nixon” the White House by “aligning actions with words.” The failure of the Carter administration to bring about the safe return of the diplomats taken hostage doomed his presidency and set the stage for a new era in U.S. policies with the election of President Ronald Reagan.

Bacevich argues American policy in the Middle East has been influenced by a small group of conservative policy makers; namely Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz, who first worked in the Nixon administration and then worked in the Reagan and both Bush Administrations while sitting out the Carter and Clinton administrations in conservative think tanks. Wolfowitz wrote while serving as the assistant secretary of defense for regional programs, “Demonstrating a willingness to take on Iraq would enable the United States to maintain the region’s precarious stability or at the very least to make other threats manageable.”

“Oil was not the problem; rather, America’s oil addiction signified something far, far more troubling—a people that had lost its [their] moral bearings.”

Bacevich ventures geographically out of the Middle East to include the Bosnian and Kosovo Wars, which were fought in the northern reaches of the former Ottoman Empire. What is unique to these two wars is that the U.S. entered the conflicts to protect Muslims and, in both wars, foreign fighters fresh from the war in Afghanistan joined local Muslim armies and militias. Additionally, the governments of Saudi Arabia and Iran “competed with one another in funneling weapons” into Bosnia. Both countries would be seen again in looming wars throughout the Middle East.

“…Quarrels in the region were not really about age-old religious differences but rather the result of many unscrupulous and manipulative leaders seeking their own power and wealth at the expense of ordinary people.” Gen. Wesley Clark, Commander Operation Allied Force.

The policies of each U.S. president have, for the most part, been reactive to events and lacked the overarching strategy needed to bring about success. Bacevich offers that during the Kosovo War, General Clark observed, “pushing to escalate and intensify was the strategy” of ending the war. While in the Middle East, “In truth, as President Clinton deepened U.S. military involvement in the region, he (like his immediate predecessors) never devised anything remotely approximating an actual strategy.”

Bacevich asserts, that NATO’s Operation Allied Force, the Kosovo air war, “offered compelling evidence to suggest that senior U.S. military officers—even supposedly bright ones—were strategically challenged.” Bacevich’s observation would ring true as the U.S. faced its newest threat Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda, which the U.S. first approached as a quasi-law-enforcement operation and used the military only to launch “limited military retaliation.”

Bacevich approaches the first months of President George W. Bush’s administration as setting the stage for Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Cheney to implement the policies that were bantered about early in their public careers. “The events of 9/11 created the opportunity to act on this perceived imperative.” In doing so, the administration opted to put Saddam Hussein and Iraq in their sights while overlooking Saudi Arabia, the “homeland” of the majority of the 9/11 attackers. Looking back at Bacevich’s earlier statement regarding oil as the prime motivator of U.S. policies, he writes.

“…oil had become an afterthought. Ultimately, the war’s architects were seeking to perpetuate the privileged status that most Americans take as their birthright. Doing so meant laying a new set of rules—expanding the prerogatives exercised by the world’s sole superpower and thereby extending the American Century in perpetuity.”

The controversial decisions and actions made by both the Bush and Obama administrations in fighting the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and many lesser known places in what would be known as the Global War on Terror will be examined for years to come. Bacevich’s views of the Bush and Obama era of the Middle East wars joins others that see them as strategic blunders. He makes an interesting argument, however, on whether the U.S. had committed war crimes, quoting the 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal, “To initiate a war of aggression is the supreme international crime in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil as a whole.”

Readers may find Bacevich’s America’s Greater War for the Middle East links what may appear as dissimilar events in his interpretation of U.S. actions in the Middle East. However, Bacevich leads the reader through the various events showing how the second and third effects of acting without a strategy to win or strategic vision for the future makes the book well worth reading.

Dave Mattingly is a writer and national security consultant. He retired from the U.S. Navy with over thirty years of service. He is a member of the Military Writers Guild, NETGALLEY Challenge 2015, and a NETGALLEY Professional Reader. This article represents the private views and opinions of the author and do not reflect those of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, of the U.S. Government

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] The authors description of then Chief of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen Dempsey speaking to press August 21, 2014.

[2] David Rapport argues that there have been four waves of rebel terror usually lasting 40-45 years; The Anarchist Wave, The Anti-Colonial Wave, New Left Wave, and lastly The Religious Wave. The Skyes-Picot agreement would be considered part the second wave of rebel terror.

[3] Events of the 1970s including the Iranian Revolution are the beginning of Rapoport’s Religious Wave.