Developing leaders is one the most important endeavors within the military profession. More specifically, establishing the core of “expert knowledge” essential to winning wars defines the profession. In spite of senior leader emphasis to commit to self-development, one of the paths critical to accruing tacit knowledge, many leaders fail to adequately commit themselves to goal-oriented self-study. Considering this important context, while today’s leaders arguably constitute the most “combat-experienced force” fielded in recent memory, much of this experience reflects over a decade principally focused on counterinsurgency that may be only partially relevant for other strategic challenges.

The military services must ensure leaders are capable of operating in an increasingly uncertain, dynamic, and volatile international security environment. Ironically, the military services’ comprehensive approach to developing leaders requires individual participation in independent study, yet years of surveys sponsored by organizations such as the Center for Army Leadership acknowledge that competition for time available to personal study limits these efforts. While the most recent report shows improvement in self-development from previous years, in the case of the Army just over half of leaders believe that their self-development has a “large impact” on their development. Some of these studies reveal more significant shortfalls that leaders do not know how to focus their personal strategy for learning, or worse they simply expect that “development is something provided by others.” The resulting imbalance in leader development efforts not only limits personal development, but also limits the potential of the profession writ-large.

Given these unexceptional statistics, as leaders progress through more senior levels of leadership they will inevitably find themselves promoting, justifying, convincing, or mandating that their subordinates participate in self-development. The refrain, “it worked for me,” is no longer sufficient explanation for younger cohorts accustomed to accessing information on virtually any topic in an instant. As a result, young leaders may not appreciate that effort invested in rigorous study is essential to accruing tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is not “received wisdom” or something you can look up. The journey and reflection in study results in knowledge on a range of topics that is difficult to codify or transfer between leaders. Tacit knowledge is also essential to intuition and practical and emotional intelligence. Lastly, not only is tacit knowledge important to the profession, but it is also available to leaders without the use of their smartphone or other device.

The Army Leader Development Model

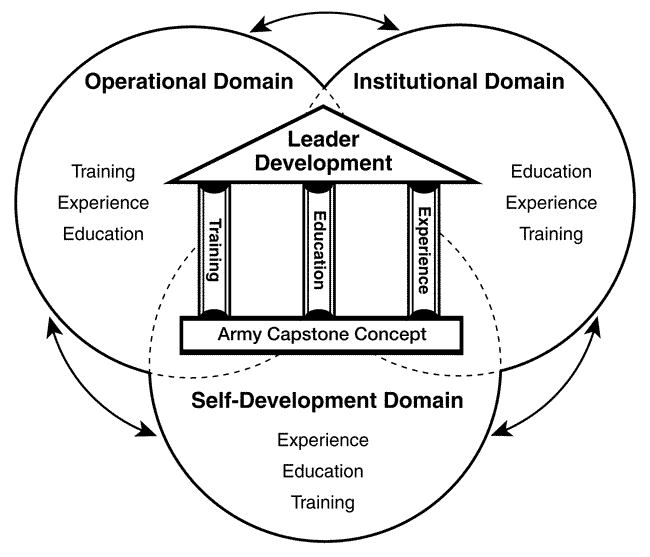

As an example of how the military services develop their leaders, we can assess the Army Leader Development model (Figure 1), which is based on the relationship among the three mutually supporting domains of learning that contribute to developing leadership skills and attributes progressively throughout a career. These domains include the operational, institutional, and self-development domains, all of which prepare leaders for assuming additional responsibility.

Figure 1: Army Leader Development Model

The operational domain includes experience gained during contingency operations, training activities at home station, rotations at a Combat Training Center, or unit level leader professional development sessions. The institutional domain accounts for attendance at schools and professional military education (PME) to obtain knowledge, skills, and practice necessary to perform critical tasks. Both the operational domain and the institutional domain develop leaders in establishing explicit knowledge, easily codified and articulated.

The self-development domain is an individual responsibility and consists of independent study to enhance learning in the operational and institutional domain, address gaps in skills and knowledge, or prepare for future responsibilities. In addition, the self-development domain includes three types of self-development: structured, guided, and personal. Structured self-development is required, planned, goal-oriented learning sponsored by the institution. Guided self-development is optional learning that follows a progressive sequence with contributions from the chain of command, and personal self-development is initiated and defined by the individual. Self-development also includes personal reflection on learning and experiences from both the operational and institutional domain. This reflection and self-study builds the foundation of tacit knowledge that, when combined with their range of explicit knowledge, allows leaders to better achieve their potential.

Each of these domains is necessary for effective leader development, but none is sufficient by itself. Yet the combination of time constraints, pace of operations, and personal choice result in less attention paid to the institutional and self-development domains. While leaders rely heavily on experience in the operational domain, the decreased reliance on institutional and self-development results in a narrow range of expertise only partially relevant for future scenarios. This situation is a source of great risk in the next “first battle.”

In hindsight, today’s imbalance in leader development efforts is easily explained.

In hindsight, today’s imbalance in leader development efforts is easily explained. Repeat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan provided unprecedented opportunities for learning within the operational domain. In some cases, however, frequent deployments reduced opportunities within the institutional and self-development domains. Primary examples of this case include the backlog of mid-grade officers needing to attend professional military education and the lack of time available for self-development opportunities given the pace of operations. In the effort to address short-term challenges and keep “combat seasoned leaders in the fight,” officers are delayed or waived attendance at professional military schools. Ultimately, this compromised long-term benefits of progressive learning within the institutional domain. While the Army recently returned to the practice of selecting the top half of their most talented officers for intermediate-level education, professional military education venues generally lag in documenting operational lessons to share within the institutional domain.

Again, perhaps as an example of poor self-development within the military writ large, Army doctrine already directs leaders to participate in self-development, yet the statistics reveal an outcome otherwise. The Center for Army Leadership’s Annual Surveys of Army Leadership reveal the negative trend that leaders, particularly company grade officers, pay less attention to the self-development domain than the others. In addition, all leaders surveyed maintain that education from the institutional domain is less beneficial to their development than experience gained in the operational domain.

Tacit Knowledge Defined

In highlighting personal self-development, this article does not discount the importance of the operational and institutional domains. These domains clearly serve as a foundation in developing critical thinking and problem solving skills essential to preparing leaders and units for dynamic environments. Yet experience, education, and training gained in the operational and institutional domains simply cannot address all possible future scenarios.

The accrual of personal knowledge, whether explicit knowledge gained through training, education, and repetition, or tacit knowledge gained from personal study, experience, and reflection, enhances the ability to implement creative solutions and mitigate uncertainty. Where increases in explicit knowledge result directly from formal instruction or traditional study, tacit knowledge “resists introspection and articulation…[and is] defined as knowledge that people do not know they have and/or find difficult to articulate.” Tacit knowledge is also “personal knowledge drawn from everyday experience that helps individuals solve real-world practical problems.” Tacit knowledge is not only a measure of practical intelligence, but it is also essential to intuition and provides more innate opportunity to adapt to and shape the environment around us.

A 1998 Army Research Institute study of tacit knowledge revealed its many practical benefits. This study compared tacit knowledge inventories among a sampling of platoon leaders, company commanders, and battalion commanders, and evaluated the relationship between tacit knowledge and military leadership; quantified whether tacit knowledge was an indicator of success; and assessed applicability of tacit knowledge in leader development. The study revealed that at all three echelons assessed (platoon, company, and battalion), tacit knowledge ratings directly correlated with ratings of effectiveness among superiors, peers, and subordinates. Furthermore, increased tacit knowledge among battalion commanders clearly assisted them in “communicating a vision, helping subordinates identify strengths and weaknesses, and using subordinates as change agents.”

Intuitively combining tacit knowledge with broader explicit knowledge gained through personal self-development improves practical intelligence and cannot help but improve the profession’s ability respond to uncertainty. When leaders face an uncertain and unpredictable environment, success on the battlefield places a premium on improvisation, an essential component of mental agility. Improvisation is about “making something out of previous experience and knowledge.” Self-development efforts that deliberately seek to explore a wide range of unfamiliar topics only broaden the foundation of explicit knowledge necessary for problem solving in uncertain, complex environments.

Commit to Self-Study

The significant limitation of personal self-development is that it remains an individual responsibility. As Army doctrine acknowledges, “For self-development to be effective, all Soldiers must be completely honest with themselves to understand personal strengths and gaps in knowledge…and then take the appropriate, continuing steps.” In reality, the 2011 Annual Survey of Army Leadership (documenting the worst trends in self-development) revealed that only about two-thirds of leaders specifically understand what to address in support of their own self-development. This deficiency was particularly evident in the ranks of company grade officers, where only 56% of these officers understood where they should focus self-development efforts. In addition, the survey reflected less time afforded to participate in self-development. Only 59% of leaders surveyed believed their superiors expected them to participate in self-development (down from 64% the year prior). Among the leaders who thought their superiors supported self-development, only half agreed that the chain of command provides the requisite time to accomplish self-development.

Internalizing self-development efforts throughout entire cohorts of military leaders will increase intellectual capacity, leverage practical, emotional, and social intelligence, and increase attention and awareness.

Given these statistics, the profession is left with two options. The first option would be establishing an “accountable and reportable” self-development program (separate from structured self-development for non-commissioned officers that more closely resembles learning in the institutional domain). Accountability will increase dialogue and awareness to better focus self-development efforts, and reporting these efforts would offer opportunities to identify sources of tacit knowledge among the force that could be applied to yet unknown challenges. The second option is to remind officers of their sworn commitment upon commissioning, as captured in Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall’s first edition of the Armed Forces Officer. This commitment both inspires and reminds, “the commissioned person must constantly and relentlessly acquire and reacquire the justifications of officership in order to be worthy of the title of officer.” Marshall specified that this depended on an officer’s willingness to acquire knowledge and internalize duty and service.

The varied operational and institutional opportunities inherent to the Army Leader Development Model already reinforce critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Internalizing self-development efforts throughout entire cohorts of military leaders will increase intellectual capacity, leverage practical, emotional, and social intelligence, and increase attention and awareness. This team effort will also invest in the long-term development of leaders better prepared for the uncertain strategic horizon.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.