How to Be Right in the Ways that Matter

George Edward Pelham Box, introduced to statistics while studying chemical weapons during World War II, would become the Director of the Statistical Research Group at Princeton, create the Department of Statistics at the University of Wisconsin, and exert such influence on modern statistics that one might say a working statistician owes much of his or her craft to this man whether they know it or not.

Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to introduce George Box … but he hardly needs an introduction. You already know him and no doubt quote him regularly. Let me prove it. George Box coined the phrase, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

We’ve all heard this aphorism, even if we do not know it springs from George Box. And while it’s true, what isn’t widely understood is how dangerous and damaging the idea is and why we should ruthlessly suppress its use.

Listen carefully the next time you hear the mantra produced. The key to its perfidy is the manner in which most use it, emphasizing the first half as exculpatory (“It doesn’t matter that my model is wrong, since all models are”) and the latter half as permissive. The forgiveness of intellectual sins implicit in the first half requires of the analyst or programmatic and planning partisan no examination of the sin and its consequences; we are forgiven for we know not what we do.

The utility of the model is elevated as the only criterion of interest, but this is a criterion with no definition and admits all manner of pathologies.

Once forgiven, the utility of the model is elevated as the only criterion of interest, but this is a criterion with no definition and admits all manner of pathologies that contradict the original intent. Consider another reference to the same concept by Box: “Remember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.” His notion of utility is tied explicitly to the question of how wrong the model is or is not. This is precisely the emphasis in Einstein’s famous injunction:

It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.

It is the phenomenon under investigation, the datum of experience, that forms the basis for evaluating the relative utility of the model that is, of necessity, not a perfect representation of the phenomenon. The question is not whether the model is right or wrong, useful or useless. The real question of interest is whether the model is right in the ways that matter. The two concepts, separated by a lowly conjunction in Box’s famed quote, are not separate in his intellectual construct. Yet they are very much so in the framing of the quote as typically (ab)used.

Why does this matter? What does it mean for a model to be useful? Does it mean useful in the sense that it illustrates and illuminates some natural phenomenon, as Box would have it? Or does it mean the model is simple enough to be understood by a non-technical audience? Or perhaps it means the model is simple in the sense that Herbert Weisberg uses to characterize willful ignorance, “simplifying our understanding in order to quantify our uncertainty as mathematical probability.” Or does it mean we get to represent reality in a way that facilitates digital representation or particular solutions we prefer. If any of these begin to affect our assertions regarding utility, we have crossed over to the dark side, a territory where utility becomes a permissive cause for failure, and that is a dangerous territory indeed.

These questions affect every aspect of nearly every problem a military analyst will face.

Huc Sunt Dracones

Critically, these questions affect every aspect of nearly every problem a military analyst will face — whether that analyst is an operations research analyst, an intelligence analyst, a strategist engaged in course of action analysis, etc. Examples abound, but one is so ubiquitous as to attract special attention.

Consider the model of risk we know and love, expected value expressed as a product of probability and consequence. With no meaningful characterization of the underlying distribution in the probability half of this formula, risk is a degenerate estimate ignoring the relative likelihood of extremity. On a related note, when considering a given scenario and speaking of risk, are we considering the likelihood of a given scenario (by definition asymptotically close to zero) or the likelihood of some scenario of a given type? This sounds a bit academic, but it is also the sort of subtle phenomenon that can influence our thinking based on the assessment frame we adopt.

This isn’t the end of the issue vis-à-vis probability, though, and there are deeper questions about the models we use as we seek some objective concept of probability to drive our decisions. The very notion of an objective probability is (or at least once was and probably still should be) open to doubt.

John Maynard Keynes, a mathematician and philosopher long before be became the father of modern macroeconomics.

It’s instructive to ponder A Treatise on Probability, a seminal work of John Maynard Keynes, or Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit by Frank H. Knight, both first published in 1921. In the formative days of the modern theory of probability, these men put forward a notion of probability as inherently subjective. Knight, for example, explicitly includes in his notion of risk the question of confidence: “The action which follows upon an opinion depends as much upon the confidence in that opinion as upon the favorableness of the opinion itself.” But if subjectivity is inherent to assessments of probability and risk, we enter into all manner of human cognitive silliness. Does increasing information increase the objective assessment of probability, the subjective assessment of confidence, both, or neither? There is some evidence to suggest the second and not the first, with all manner of impacts on how we conceive of strategy and planning.

The question of consequence as a measure of risk is no less problematic. What do we mean by consequence and how do we quantify it? How does the need for a quantifiable expression of consequence shape the classes of events and outcomes we consider? Does it bias the questions we ask and information we collect, shifting the world subtly into a frame compatible with our mode of orienting to it? What are the consequences of being wrong?

This model may be useful — it certainly makes the complex simple — but is it right in the ways that matter?

The continuum of Conflict as illustrated in the 2015 U.S National Military Strategy

But even if problematic at the level described, there is a utility in this approach, if only because it simplifies our understanding of conflict. In this model, we can assign to each scenario a nicely ordered numerical value, and we suddenly have a continuum. But this continuum makes each type of conflict effectively similar, differing only in degree. The very idea of such a continuum is dangerous if it leads military planners to believe the appropriate ways and means associated with these forms of conflict are identical or that one form of conflict can be compartmentalized in our thinking. This model may be useful — it certainly makes the complex simple — but is it right in the ways that matter?

Importantly, we are faced in the end with a model and not with reality.

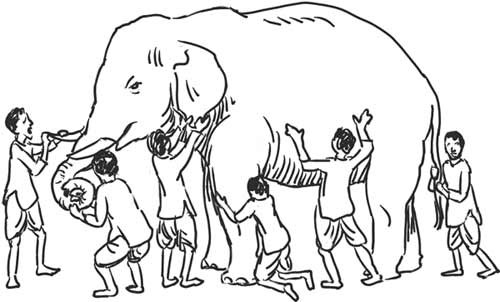

Blind Men Building Models of an Elephant

Importantly, we are faced in the end with a model and not with reality; we are faced with approximations of truth and not with real truth, with maps of the landscape and not the landscape itself. This notion is particularly important in thinking about the utility of our models. The need is always an “adequate representation of a single datum of experience.” But in studying our models we can become detached from experience and attach ourselves to the models themselves, associate our intellectual worth with their form and behavior, and make them into things worthy of study unto themselves. In short, we are wont to reify them, a process Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman describe as

… the apprehension of the products of human activity as if they were something else than human products-such as facts of nature, results of cosmic laws, or manifestations of divine will. Reification implies that man is capable of forgetting his own authorship of the human world, and further, that the dialectic between man, the producer, and his products is lost to consciousness. The reified world is … experienced by man as a strange facticity, an opus alienum over which he has no control rather than as the opus proprium of his own productive activity.

This suggests an important remedy to the problem of models that are wrong in ways that matter. If we recognize them as the products of human activity and not as handed down from authority, then they can be superseded by new products of human ingenuity. They are not sacred, and when we say a model is wrong, our next thought should never be to apologize, and our next word should never be “but.”

It isn’t enough to know that we are wrong.

It is important to know the ways in which we are wrong.

W. Edwards Deming, a statistician who revolutionized industrial processes, has some useful advice to offer, in this regard. “The better we understand the limitations of an inference … the more useful becomes the inference.” It isn’t enough to know that we are wrong. It is important to know the ways in which we are wrong so that we may turn our attention to whether or not our models are right in the ways that matter.

And if the model is wrong, we must demand a new model more closely aligned to the question of interest, a model right enough to be useful. And this is not just a task for analysts and mathematicians, though it is our duty. This is a task for planners, strategists, operators, decision makers, and everyone else. We must seek the truth, even if we may not find it in all its Platonic perfection and even if its pursuit is paradoxical in the sense that it requires both humility and the belief that we can reach toward perfection.

Irony aside, though, a good first step is to scrub Box’s exculpatory and damaging aphorism from our decision-making discourse.

Eric M. Murphy is a mathematician, operations research analyst, and strategist for the United States Air Force. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are his alone and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.