The Tenets of Leadership Are Unchanging

Military leadership comes in all different forms. It can be embodied in the leadership of troops on a battlefield, or it can occur behind the scenes in moments no less important. The Army defines leadership as influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to improve the organization and accomplish the mission. These bland, doctrinal terms are best brought to life in the form of historical vignettes, a valuable tool for teaching the process of leadership.

Brigadier General John Buford —

Extends Influence Outside the Chain of Command

General John Buford (NARA)

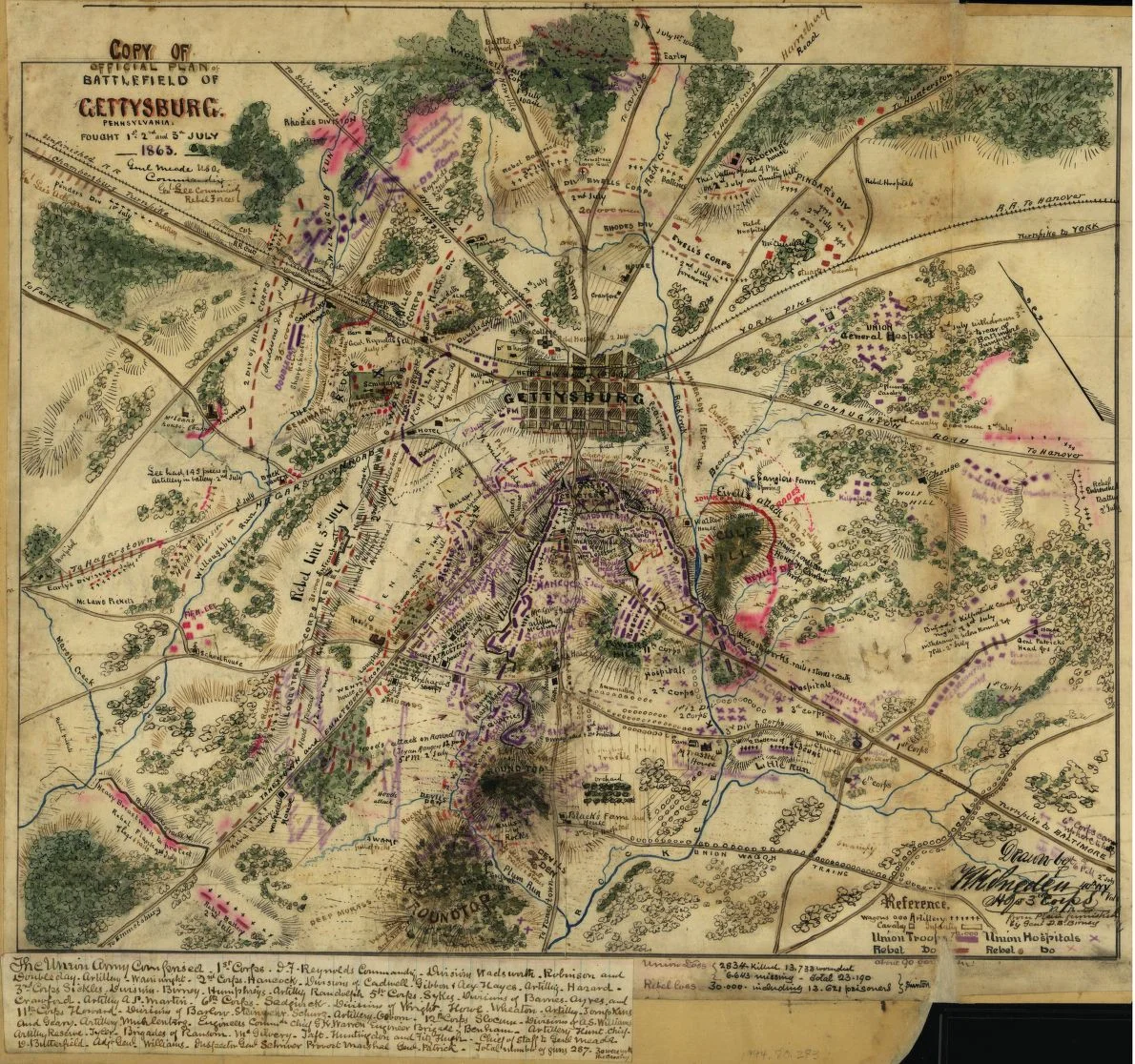

The ability to influence people, especially under the duress of combat, is the paramount skill of exceptional leaders. This includes the ability to influence not just subordinates but superiors as well. Many times, leaders are confronted with a situation in which they must take action even when there are no direct orders. When cavalry officer John Buford arrived in Gettysburg on June 30, 1863, with his division of cavalry, he instinctively saw the importance of the terrain outside the town and how the enemy could utilize it. He knew the Confederate axis of advance would lead them to Gettysburg with superior numbers where they could then establish a blocking position dangerous for the Union Army of the Potomac.

Without direct orders, he arrayed his two brigades in forward defensive positions to delay the Confederates until follow-on Union infantry could arrive. That night he sent off a message to the commander of the Union I Corps, Major General John Reynolds, alerting him to the strong enemy presence in the area and advising him that he would hold his ground in the morning pending further guidance. Buford took ownership of the tactical decision on the battlefield and made immediate adjustments with the information available.

Buford was aware of the trust Reynolds had in him and could make decisions assured of his superior’s support.

Buford could do so with confidence as he had two important things on his side: the loyalty and trust of his soldiers and the trust of his superiors. Buford was a noted fighter, both in the west before the war and in the early years of the war. He was wounded leading a cavalry charge at Second Bull Run in 1862, where he cut his teeth as a cavalry commander fighting a rear guard action. During this fight, he failed to commit his entire force and suffered a close defeat to a superior force. Demonstrating his resilience, Buford learned from his mistake and never again held a reserve during battle. Buford trained and developed excellence in his cavalry across all tasks: scouting, counter-reconnaissance, and screening. They knew from their multiple clashes with the enemy that they could best them mounted and dismounted, which imbued them with confidence. Buford was also on excellent terms with his superiors, in particular John Reynolds, who now commanded the Union I Corps and a wing of the Army of the Potomac on the march. Buford was aware of the trust Reynolds had in him and could make decisions assured of his superior’s support.

On the morning of July 1, as Buford had predicted, a Confederate division did converge on his position. Buford fought a delaying action in depth that forced the Confederates to deploy in line of battle. During this time, Union infantry arrived on the field and stabilized the lines. Due to Buford’s assessment of the terrain, his ability to make quick decisions in absence of authority, and the mutual trust he had with his men, the vital terrain of Cemetery Hill, Culp’s Hill, and Cemetery Ridge were retained.

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock —

Charismatic Leadership

Winfield Scott Hancock (NARA)

Leaders are made, not born. So says Army doctrine on leadership. They are continuously learning and honing their skills. However, one cannot be a disconnected leader. Charisma is an unquantifiable force multiplier, and on the evening of July 1, General Winfield Scott Hancock demonstrated how the power of personality can be used in a crisis. Following Buford’s stand, two Union corps of infantry took up positions outside the town of Gettysburg but were overwhelmed by superior Confederate forces. Reynolds himself was killed early in the fighting. The battered and retreating Union troops fled back through the town of Gettysburg towards the rear — wherever that might be. One small division had been kept in reserve and was posted on Cemetery Hill, a commanding eminence overlooking the town. Stragglers began to collect around this one unit and chaos reigned as units struggled, leaderless, to find some direction. Not far behind them were Confederate troops hoping to finish off the battle before night fell.

His very presence on the field boosted morale.

Arriving on the field at this critical junction was the young Hancock. As one officer noted, “Upon horseback I think he was the most magnificent looking General in the whole Army of the Potomac at that time.”[1] His aura was such that men gravitated to him, looking for leadership. A veteran commander in the Army of the Potomac, he had already earned the nickname “Hancock the Superb” because of his demeanor. His very presence on the field boosted morale.

With optional orders from the commander of the Army of the Potomac to fall back to secondary defensive positions, Hancock instead, after viewing the ground, decided to stay and fight. He organized the Union defensive line hinged on Cemetery Hill, with its right flank on Cemetery Ridge and the left flank on Culp’s Hill. Retreating units rallied and formed around the key positions, turning the day’s defeat into what would become overall victory from the strength of the defensive position. Hancock’s swift decision-making and powerful personality preserved the Union army’s strength and allowed for a successful defense during the battle.

Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery —

Innovative and Adaptive Leadership

Freeman McGilvery (Maine State Archives)

There are several different kinds of courage. It takes courage to lead troops in battle. It takes courage to confront disciplinary issues, as Joshua Chamberlain did with the mutineers from the 2nd Maine. It also takes courage to innovate and adapt, especially when the original plan goes to pieces. This is just what Lieutenant Colonel McGilvery did on the afternoon of July 2.

As the Union III Corps under Major General Daniel Sickles moved forward without orders to occupy higher ground in front of Cemetery Ridge, a massive gap developed in the Union line. This gap became dangerous after Sickles’ corps got run over by a massive Confederate attack on the afternoon of July 2. A former sailor, now in command of the Army of the Potomac’s Reserve Artillery Brigade, McGilvery discovered that this gap was undefended even as Longstreet’s Confederates were approaching. If Longstreet broke through, he would divide the Union army and menace the flanks, just as Robert E. Lee had planned.

Recognizing he had no available infantry to plug the gap, McGilvery and his aides cobbled together as many artillery batteries as they could find, even those that had just retreated from the maelstrom, to form a thin artillery line along the Plum Run stream. This line ran from north of Little Round Top to the southern end of Cemetery Ridge and numbered no more than seventeen to twenty guns. Doctrinally, artillery were not considered effective unless supported by infantry. McGilvery had no infantry, a fact that did not escape the attacking Confederates, who numbered close to three brigades.

Any sane person would have given up the position as lost and retreated, but McGilvery quite literally stuck to his guns.

Time and again the jubilant Rebels closed on McGilvery’s lines only to be blasted back by canister and grapeshot. They eventually closed on individual fieldpieces, silencing the guns with accurate rifle fire. At one point, McGilvery was down to only six available fieldpieces, with many guns running out of ammunition. Any sane person would have given up the position as lost and retreated, but McGilvery quite literally stuck to his guns, personally directing fire and shifting guns for the best effect even after having several horses shot out from under him. He had given the order to “hold at all hazards,” an order that he personally kept even as his little command dwindled.

Sketch of the 9th Massachusetts Battery moving into position on the Plum Run Line (Library of Congress)

As dusk fell on the battlefield, McGilvery had been holding his unorthodox line alone and unaided for an hour. Reinforcements of infantry finally began to arrive to stabilize the line and McGilvery could withdraw his makeshift command to safety. Through his undaunted tenacity, refusal to quit, and ability to adapt in the face of adversity, he had saved the Union center from disaster.

Army doctrine is often criticized for being too stiff and unwieldy, but every example laid out here supports of one of the principles laid out in Army Doctrine Publication 6–22, Army Leadership. The words we use to describe leadership may change over the years, but the tenets of leadership are unchanging.

Angry Staff Officer is an officer in the Army National Guard and a member of theMilitary Writers Guild. He commissioned as an engineer officer after spending time as an enlisted infantryman. He has done one tour in Afghanistan as part of U.S. and Coalition retrograde operations. With a BA and an MA in history, he currently serves as a full-time Army Historian. The opinions expressed are his alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. For more from Angry Staff Officer, visit his Wordpress blog site.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Notes:

[1] Frank Haskell, Account of the Battle of Gettysburg.