Suicide bombings are nothing new — it is a tactic that been in use since the early 1980s — but it has typically been a man’s game. Until recently, that is. There is no place where female suicide bombers have blossomed more than in the Caucasus region of Russia: Chechnya and Dagestan. The practice of suicide bombings did not originate here but seems to be thriving in the Caucasus.

Most articles that mention the women almost always refer to them as ‘Black Widows.’ It is easy to label their actions as born from grief and anger. It is understandable as years of violence have taken their toll on countless families in the form of physical casualties and mental scarring. To call these women who choose to kill themselves and others grieving widows only tells part of the story. The history of Chechen-Russian relations, the impact of Islam on the region, and the culture itself all play a role in this complicated story. Knowing some of this history may well explain their motives.

History

The conflict between Russia and the Chechens has been going on for hundreds of years. Russia has been trying to dominate the region — with varying degrees of success — since the 1700s, as it was a major route south to Turkey. In 1785, a holy war was declared against the Russian infidels, and the clans of the region were encouraged to join forces against the Russians. The Chechens held off the Russians for many years until the annexation of the region in 1859. By then, the Muslim leader, Imam Shamil had been captured. The Russian governors of the region seemed to take great pleasure in their mistreatment of the peoples of the North Caucasus. It was so terrible that thousands of Caucasians fled, many to Turkey.

“The morning of the Streltsy execution” by Vasily Ivanovich Surikov.

The October Revolution of 1917 opened a new chapter in the North Caucasus. After siding with the Bolsheviks, the Chechens gained a sort of autonomy. Unfortunately, it dissolved during in-fighting between pro- and anti-Bolshevik Chechens. Following the end of the conflict, the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Chechen-Ingush Republic was established in 1936. Largely autonomous in name only, the republic was ultimately under Soviet rule.

Following Stalin’s death, the Chechens were allowed to return to their homeland in 1957.

One of the worst chapters in Chechen-Russian relations came at the hands of Stalin during the Second World War. In 1944, Stalin ordered the deportation of Chechens out of the North Caucasus. Hundreds of thousands of Chechens were loaded onto trains and sent to points east, around Kazakhstan. The official reason was to remove German collaborators, but many agree it was to rid the region of the Chechens, who proved troublesome to the Soviets. Following Stalin’s death, the Chechens were allowed to return to their homeland in 1957. The Chechen-Ingush Republic was established, under Soviet leadership.

Largely, the North Caucasus stayed calm until the fall of the Soviet Union. In the decades following the return of Chechens from deportation, ethnic tensions simmered as Chechens were generally treated as lower class citizens. In 1990, the All-National Congress of the Chechen People was formed and broke away from the Chechen-Ingush Republic. The Congress’s leader, Dzhokhar Dudaev, laid the groundwork for establishing an independent state of Chechnya. President Boris Yeltsin called this move illegal, and sent Interior Ministry troops to Chechnya. Chechen guerrillas surrounded the troops and forced them out, collecting weapons and equipment the troops left behind.

Yeltsin appearing on TV announcing his resignation on 31 December 1999

In 1994, Yeltsin ordered the invasion of Chechnya to retake Grozny, and to suppress any additional resistance. Initially, the Russians made progress, securing Grozny. But the Chechens had the upper hand; they were determined, well-armed, and at home in the tough, mountainous terrain of Chechnya. Yeltsin realized he wasn’t going to win, so in 1996 he struck a deal with the Chechens to withdraw Russian troops, thereby making Chechnya a de facto independent state. Sharia law was even introduced in early 1999. Chechnya was on a road to make itself a more Islamic republic.

But the Second Chechen War put a stop to that. When Vladimir Putin became prime minister of Russia in 1999, he decided to make face-saving point with Chechnya. He sent in the professional army to suppress the new Chechen insurgency, who had recently invaded neighboring Dagestan. Grozny was bombarded, towns and villages destroyed, people suspected of collaborating with the insurgency were rounded up, many never to return. The Russians continued their campaign for years, leaving Chechnya an empty shell of what it once was. Almost every family was affected by the destruction and violence. One Chechen rebel leader, Akhmed Kadyrov, decided it wasn’t worth fighting any longer, and struck a deal with the Russians. Putin made Kadyrov head of the republic, under Moscow’s authority. Fighting largely ceased, but a smaller insurgent campaign began. Anti-Russian Chechens wanted independence, and the establishment of an Islamic state.

Islam

Islam has played a large role in Chechnya and the North Caucasus, and in turn is a piece of the puzzle of the Black Widows. The evolution of the religion of the area shaped the minds and actions of those who follow.

Islam first spread through the region in the form of Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam. The Naqshbandi Sufi order was the first to gain a foothold in Chechnya, spread through missionaries and scholars. Its disciples were clannish in behavior, which fit in well with the clan-based culture in Chechnya. Chechen Muslim and Sufi leader Shaykh Mansur was the first to declare a holy war against the invading Russians in 1785. After the Russian occupation, the Naqshbandi began a guerrilla war that would last until the forced annexation of Chechnya by Russia. After his capture — and subsequent death — Muslim resistance against the Russians was led by Imam Shamil. He established a sort of Islamic state, and successfully resisted the Russians until his capture in 1859. After the capture of Shamil, the Qadiri order gained popularity. At first, they attempted to create peace with the Russians. Their popularity grew so quickly that it spooked the Russians, who began renewed violence against them. The fate of thousands of Chechens was death. The Naqshbandi joined the Qadiri in a prolonged, but largely ineffective, resistance against the Russians into the 20th Century.

During the Revolution, the Chechens fought alongside the Reds in the civil war with the White Army against the tsar. The new Soviet government issued a declaration to the Muslims of Russia: “Henceforth your beliefs and customs, your national and cultural institutions are to be free in violate…Your rights, like the rights of all the peoples of Russia, are under the mighty protection of the revolution.” The relationship between the Soviets and Muslims was fairly ambivalent, at first. There were minor insurgencies, but one uprising in 1925, led by Uzun Haji, caused the Soviets to crackdown. The Sufi Muslims were labeled criminals or counter-revolutionaries. The leaders dug in, relying on the tight bonds of their religion and of the clans to protect and preserve the brotherhood, the religion. The Soviets began systematically arresting, deporting and executing Chechen Muslims that would continue up to the mass deportation in 1944.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Chechnya’s secular government took steps to restore Islamic traditions in the region. Chechen president Dzhokhar Dudaev thought religious belief could be a foundation on which he could declare Islam the national religion, and create an Islamic state. Around the same time, missionaries arrived in the region from Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. These “preachers of Islam” represented Salafi Jihadi — a brand of political fundamentalist Islam generally called Wahhabis. They encouraged the Sufi Chechens to reject Sufism and join the Wahhabi sect. Some local Imams were even offered payments to join.

The younger generations were being brought up with Wahhabi Islam, a more radical version of Islam than what was traditionally practiced.

The idea of Jihad spread throughout most of Chechnya, especially among the younger generations. The years of repression and persecution under first the Soviets, and later the Russians, were taking their toll. The younger generations were being brought up with Wahhabi Islam, a more radical version of Islam than what was traditionally practiced. The wars caused a lot of anger in the younger Chechens, who were looking to get their revenge.

Taips

Dzhennet Abdurakhmanova, 17, posing with her late husband Umalat Magomedov. She became a “black widow” and graduated to suicide bomber, carrying out the Moscow subway bombings in April 2010.

A third piece of the puzzle rarely gets mentioned in articles about the Black Widows, but it may be the most important piece. This piece is the Chechen clan culture. This culture goes back centuries in Chechnya, and has existed long before the introduction of Islam or hatred for Russians. It is what rules the lives of Chechens. For centuries, clans, or taips as they are called, have provided for the people, and the people were strictly loyal to their taip. Taips were made up of several families, each having a chosen council of elders. The role of the elders is not necessarily to lead the taip, but to give guidance, which is more or less followed by the members of thetaip.

Not only do taips provide familial support, they enact a sort of clan justice against those who have done wrong against a taip member. It is common for members to enact revenge against the offending taip member. Defending the name and honor of the clan and its members is more important than any government or national identity. But recently, as Chechnya has had to deal with two devastating wars with Russia, the traditional revenge culture has begun to shift. No longer were taip members taking revenge against individuals, but instead on a group identified with killing Chechens: the Russians.

The Chechen Wars took a toll on the taips. Almost every family had been touched by the conflicts. It is estimated that upwards of 100,000 died in the Second Chechen war alone. This left many wives without husbands and sisters without brothers. In their grief, many turned to religion. The fundamentalist Wahhabi Islam was by then deeply imbedded in Chechen society.

Suicide Bombers

It is still unknown why women as suicide bombers are so popular in the Caucasus. Many theories abound. The Chechen Wars left deep emotional and psychological scars. The hatred for the Russians intensified. The Chechens wanted revenge, and one means of doing so was through martyrs, suicide bombers. The jihadi ideology combined with the culture of revenge. Martyrs are celebrated. Some young Chechen women romanticize about the martyrs, but find themselves marginalized after becoming widows. Some women have been widowed several times. This can push them further away from society and closer to fundamentalism and radicalization themselves. With each loss, they sink deeper and deeper into their religion. There, they found a sort of comfort, but also found a way to bring themselves closer to their dead loved ones.

Chechen teens study the Koran at an underground medrese. In today’s Chechnya, Chechen youth are quick to embrace Islam after decades of religious repression in the Soviet Union. | Images © Diana Markosian

The first reported suicide attack by a woman was in June 2000. The Second Chechen War was wrapping up, and Russia had just laid waste to the entire Chechen region in order to repress the insurgency. Khava Barayeva drove and explosives-laden truck up to the gates of a Russian Army base near her family’s village of Alkhan Yurt. The blast killed two and wounded five. Barayeva’s cousin was well-known Chechen field commander Arbi Barayeva.

From 2000 to 2005, there were a total of 25 successful bombings by Chechen women.

Since then, almost all of the attacks have come against Russian targets. Most have taken place in the North Caucasus, at military bases or Russian government offices. One notable attack took place at a religious festival in 2003. In an attempt to assassinate Russian-backed Chechen president Akhmad Kadyrov, a woman blew herself up, killing 18. (Kadyrov would be killed the following year by Chechen Islamists). From 2000 to 2005, there were a total of 25 successful bombings by Chechen women. Two well-known incidents of terrorism included females strapped with explosives, but did not die by detonation. The Dubrovka Theater and Beslan school takeovers employed a total of 21 women.

After Beslan in 2004, the Russians greatly cracked down on terrorism originating in the North Caucasus, implementing tough anti-terror laws, and engaging in operations resulting in eliminating many rebels. There were only two Black Widow incidents in 2005, and then they stopped completely. Then, in 2010, the bombings started up again. There have only been six known attacks by Black Widows from 2010 through 2013, the most well-known being the 2010 bombing of a Moscow subway station. It’s not yet known why the resurgence in bombings happened in 2010.

Why

It doesn’t tell the whole story to just say these women are acting out of grief or revenge. It is not one single thing that explains these women. Each piece of the Chechen existence intersects to make up a possible explanation. Each piece works with the next, creating a three-legged stool; all three parts must be present to work. The Chechens have had to face centuries of Russian aggression, leading to a deep, overall hatred for anything Russian. They have also been targeted for being Muslim, though not as intensely. As a new version of Islam took hold in the region, Chechen ideology changed to embrace jihad. Additionally, the taip tradition of seeking revenge against an individual was shifting to a broader idea of revenge, that against a body or a group rather than just the individual perpetrator. Since the women were most affected by the Chechen wars, they were left to deal with the anger and grief. Combine the years of hatred with radicalization and a desire for revenge, and these women have an outlet. This outlet was to sacrifice themselves in order to kill Russians as a means of revenge. Chechen Muslim women found it easier to move about without suspicion as the Chechen Muslim society is more open than more traditional Islamic societies. It was easy for them to conceal explosives under their clothes, without risk of being frisked, and approach their targets. It is worth noting that many of the women who become suicide bombers are related to Chechen insurgents.

The deep-rooted clan culture, the centuries of aggression from the Russians, and the radical ideology of the Wahhabis are all important pieces of the puzzle. Still, one final piece is missing, filled with speculation: the personal reason. The one we may never know.

Brandee Leon, a student in counter-terrorism currently residing in the great Commonwealth of Massachusetts. She also blogs about food, culture and international affairs here.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

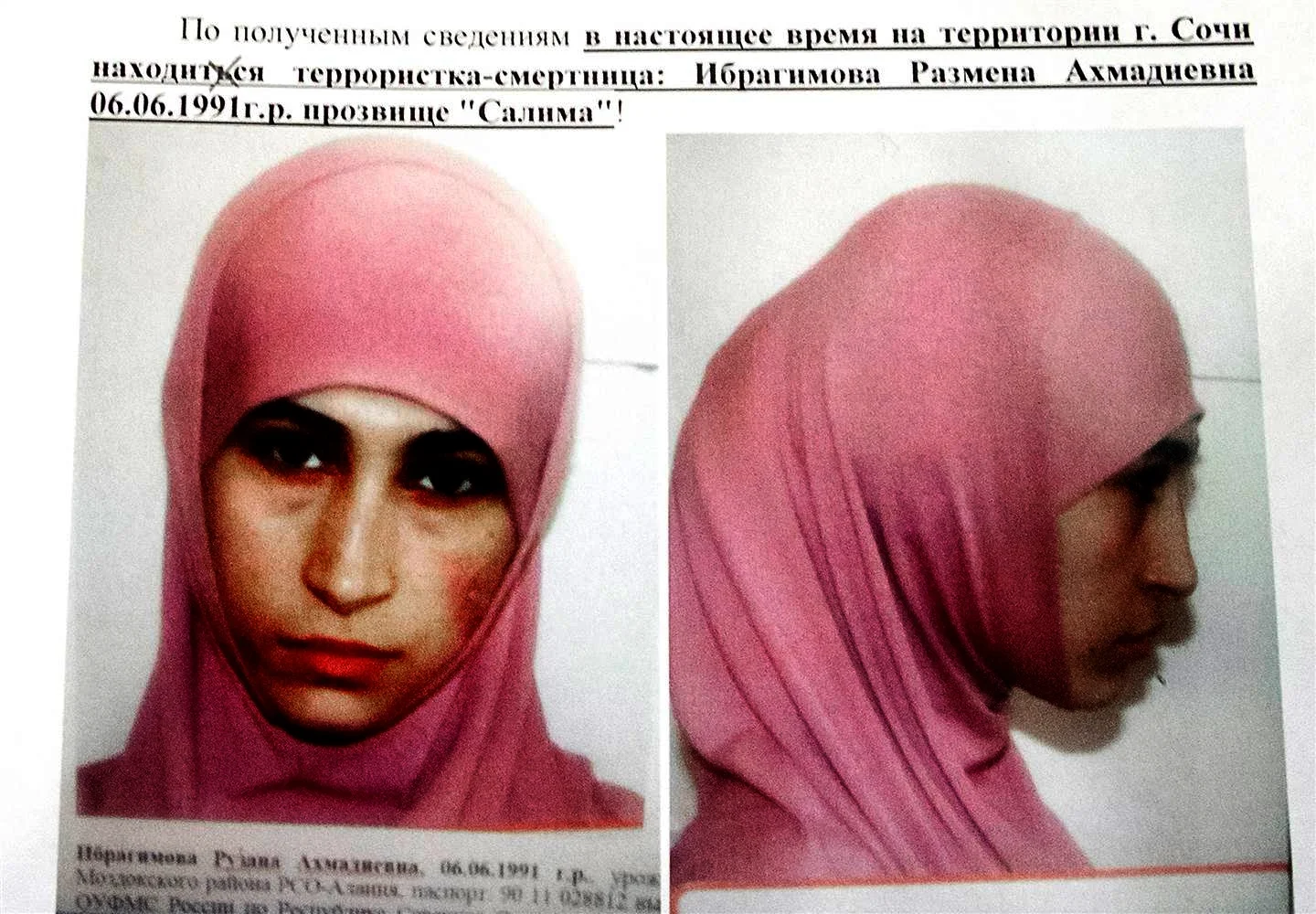

Header image: A Russian police leaflet shows Ruzanna Ibragimova, a widow of an Islamic militant, on Jan. 21, 2014. She was believed to be a threat to Sochi Olympic Games.