I think the notion of getting the North Koreans to denuclearize is probably a lost cause. They are not going to do that. That is their ticket to survival...they are under siege...they are very paranoid...the notion of giving up their nuclear capability...is a nonstarter with them.[1] — James R. Clapper, Former U.S. Director of National Intelligence

The continuum of applied U.S. strategies towards North Korea has failed and will never achieve the desired strategic objectives, as they are currently envisioned. This is because U.S. policymakers remain focused on denuclearization and non-proliferation vice regional stability as the strategic goal. In the 2015 U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) President Obama outlined his vision for leveraging “strategic patience” as a means to force the Kim regime to the negotiating table. In his view, this strategy focused on a “commitment to the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.”[2] However, because the U.S. continues to fundamentally miscalculate the underlying cultural influences guiding North Korean decision-makers and because China and Russia have failed to consistently enforce economic sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council (UNSC), strategic patience as envisioned by President Obama failed to produce the desired results. Continuing to march towards the same end-state, albeit more aggressively than before, President Trump released his 2017 NSS that asserts the U.S. “will work with allies and partners to achieve complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula and preserve the non-proliferation regime in Northeast Asia.”[3] Unfortunately, pursuing a denuclearized North Korea and convincing North Korea to agree to non-proliferation are fruitless endeavors. To understand precisely why these strategies have failed and will continue to fail, it is important to understand the cultural ideologies that influence North Korean national objectives and domestic policy actions.

NORTH KOREA: A STRATEGIC OVERVIEW

Kim Jong Un views securing nuclear weapons as a threefold benefit. First, it affords him a bargaining chip to gain international recognition of his regime; second, it serves as a means to assure regime survival against any external military threat; finally, it further assists in achieving reunification of the Korean peninsula under the North’s control.[4] Underpinning strategic decision-making in North Korea is the fundamental ideology of self-reliance called Juche.[5] Under Juche, North Korea remains focused on developing the means to achieve their national strategic objectives via a military-first doctrine that “emphasizes the need for a strong military even at the sacrifice of daily public needs” in order to counter the perceived military threat from the U.S. and South Korea.[6]

Underpinning strategic decision-making in North Korea is the fundamental ideology of self-reliance called Juche.

Although the North Korean Constitution preamble declares reunification under the leadership of the North as the “nation’s supreme task,” actions taken by the Kim regime indicate that regime survival has become the paramount priority.[7] The use of intimidation, murder, bribery, and blackmail permeate the North Korean political landscape and assist in creating a submissive and paranoid populace and elite class that allows the Kim regime to stay in power.[8] As an example, despite the massive famine of the 1990s that killed an estimated half-million North Koreans, the citizens of North Korea did not riot or rebel.[9] Moreover, national leadership holds steadfast to propagating domestic paranoia of an imminent U.S. and South Korean invasion to maintain the obedience of the masses and to justify the regime’s need to apply resources towards developing the nuclear and missile technology.[10] Controlling the domestic narrative and limiting access to outside communication remains a key element to the success of the Kim regime.

An ideology founded on negotiating from a position that allows “saving face” and an internal domestic policy of Juche underpins North Korean decision-making.[11] It is crucial to understand how past and current North Korean leaders have leveraged these cultural principles to manipulate diplomatic failures, as outlined in Appendix A, into domestic anti-U.S. fervor and as a means to justify provocative behavior.

Kim Jong Un, like his father and grandfather before him, has been able to exact control over his people by leveraging the fundamental belief that the U.S. and its Western allies are the cause of the problems affecting the population. This narrative further assists in securing domestic buy-in to the lack of public services as a means toward the capabilities to achieve Juche. Accordingly, U.S. strategies that rely on compellence (UN economic sanctions) have placed the U.S. further from achieving the desired goal of a stable Asia-Pacific region and have led to two counterproductive reactions. First, continued sanctions feed the Kim regime’s anti-U.S. narrative and help solidify China’s support to North Korea as a means to reduce the risk of instability or state collapse at their border and to maintain a strategic buffer between China and U.S. forces in South Korea. Second, sanctions serve as a national rallying cry and help justify North Korea’s military-first doctrine aimed at achieving deterrence by securing nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them intercontinentally.[12] Accordingly, the unintended consequence of strategic patience and continued sanctions has both perpetuated the suffering of North Korean citizens and failed to stop North Korea’s efforts to become a nuclear power. Therefore, U.S. policymakers must rethink their strategic approach towards dealing with North Korea in terms of the broader long-term Asia-Pacific region and pursue an alternative strategy, the goal of which must be to secure stability in support of U.S. interests, not denuclearization. Additionally, the U.S. must find a more effective way to leverage the unique relationship between China and North Korea to achieve an engagement strategy that secures long-term stability for the region.

CHINA’S STRATEGIC VIEW

Proponents of strategic patience underestimate China’s desire to maintain the status quo in North Korea, whereby the Kim regime remains in power and the border between the two countries remains controlled. Maintaining the status quo serves a twofold strategic purpose that supports China’s realist view of the issue: it secures their position as the key diplomatic power-broker between the U.S. and North Korea, and it serves as a strategic counterbalance to U.S. regional hegemonic power.[13] China requires a stable North Korea to maintain access to North Korea’s natural resources (coal and iron ore) and to minimize the possibility of a refugee crisis that would flow into China if North Korea destabilized.[14] China’s support includes “some 80 percent of North Korea’s basic supplies of food and oil” and continuous political protection despite international pressure to punish the Kim regime through sanctions.[15] As a result of the close diplomatic and economic relationship between China and North Korea and misaligned strategic priorities - a U.S. focus on denuclearization versus a Chinese focus on regime stability - U.S. policymakers have proven ineffective in getting China to support actions aimed at stopping North Korea from becoming a nuclear state.

China’s support includes “some 80 percent of North Korea’s basic supplies of food and oil” and continuous political protection despite international pressure to punish the Kim regime through sanctions.

Proponents of strategic patience admit the importance of China’s support to achieve success, yet fail to address the fact that China has remained unwilling to supporting U.S. actions. The Obama administration “waited for North Korean provocations to galvanize the PRC leadership to work with us on the problem,” but to no avail.[16] This approach wrongly assumes that China has concluded that a nuclear North Korea is as much a threat to Chinese national interests as it is to America’s. Despite public condemnation and rhetoric to the contrary, China has tacitly accepted North Korea’s actions by not consistently imposing sanctions to compel Kim Jong Un to change his provocative behavior or block his path to nuclearization. Moreover, U.S. strategists have failed to appreciate the historical significance of the Sino-North Korean relationship dating back to the Korean War and overestimate the willingness of China to support any effort that they predict has the potential of creating instability on the Korean Peninsula.

As pointed out in a recent Council on Foreign Relations essay, there are practical reasons why China wants to maintain the status quo with North Korea.[17] First, North Korea serves as a tool that provides Chinese policymakers opportunities to leverage its international “statesman” position as the power broker between the U.S. and North Korea. Maintaining a position as the regional statesman supports the Chinese narrative that they are the most influential regional player and a critical participant in brokering negotiations between the U.S. and North Korea. Second, strategic patience coupled with the outspoken pivot to Asia has been interpreted by some Chinese leaders as a strategy of containment, thereby resulting in a skeptical view of U.S. intentions regarding North Korea.[18] Third, given that a collapsed Kim regime has the potential for a historic humanitarian crisis that would spill across their shared border, China has made it clear that a stable North Korea is crucial and is the strategic priority for China. Fourth, China views North Korea as a strategic buffer between its border and South Korea, which contains a strong U.S. military presence. Finally, trade between China and North Korea was estimated at roughly $6.8 billion in 2014. Accordingly, any action taken to impose sanctions on North Korea will impact China’s economy and access to strategic minerals.[19]

This approach wrongly assumes that China has concluded that a nuclear North Korea is as much a threat to Chinese national interests as it is to America’s.

Contrary to current U.S. strategy, China views strategic dialogue and economic support to North Korea as the appropriate means to achieve long-term regional stability. Therefore, if the U.S. wants to secure regional stability that lowers the barriers to continued economic growth and prosperity for the U.S. and other regional players, policymakers must rethink their strategic approach. They must forego any strategy aimed at denuclearization through sanctions and must refocus efforts on establishing strategic lines of effort towards a stable and prosperous Asia-Pacific region. To pursue a more amenable approach, it is important to review the traditional strategies employed by U.S. policymakers with a focus on why they failed to achieve success.

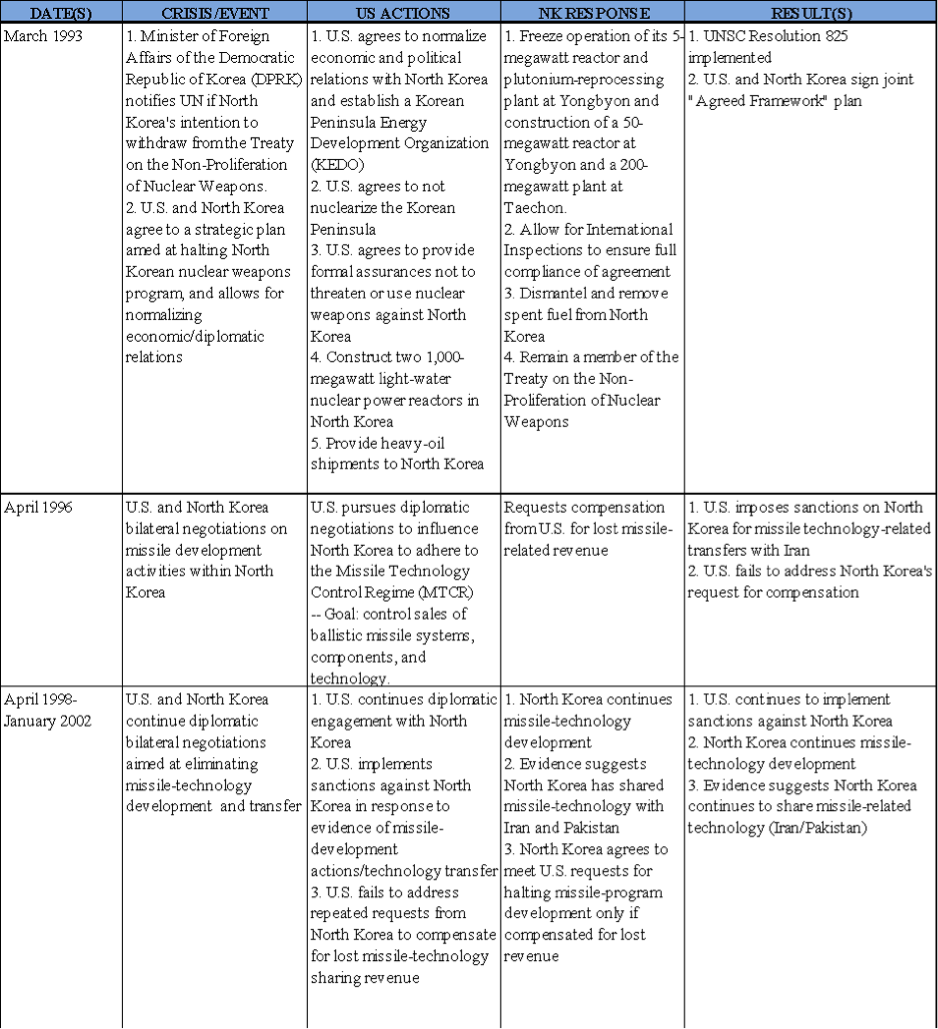

A CONTINUUM OF DIPLOMATIC FAILURES

Nuclear non-proliferation has remained the key bargaining chip used by the North Koreans in diplomatic negotiations with the U.S. and the strategic goal for U.S. policymakers attempting to solve the North Korean dilemma. However, despite their overtures to the contrary, historical evidence suggests that North Korea never wavered from their nuclear weapons or Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) ambitions. Starting in the 1990s, North Korea threatened to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NNPT) (signed in 1985), thereby initiating multiple rounds of non-nuclear proliferation negotiations with the U.S. (ref Appendix A) During the negotiations, the Clinton administration was unable to secure a long-term non-proliferation commitment from North Korea. As part of the agreed framework between the two nations, North Korea pressed for compensation as a result of lost missile sales revenue. Unfortunately, U.S. policymakers failed to realize how this lingering issue would result in North Korea backing away from further action to denuclearize and to further embrace development under the Juche ideology. Since negotiations started in the 1990s and despite continuous sanctions, North Korea has developed nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missile technology at an alarming rate. Recent estimates indicate that North Korea has “roughly 25-30 nuclear weapons, with an annual production rate of 6 to 7.”[20] Moreover, recent testing of the Hwasong-15 showed the world that North Korea has developed an ICBM capable of striking the U.S. mainland.[21]

By analyzing the strategic approach used by the U.S. through a North Korean cultural lens, one can better understand why North Korea chose to turn away from negotiating with the U.S. and why U.S. policy has failed to achieve the desired results. The sanctions imposed on North Korea during the Clinton administration were a strategic failure. Instead of compelling North Korea to reverse its pursuit of nuclear weapons, it created conditions for North Korea to become more isolated and fully inculcate Juche and the military-first doctrine as part of their national culture. Making matters worse, the strategic message expressed by the Bush administration, grouping North Korea under an “Axis of Evil” umbrella, further alienated the Kim regime and reinforced the need to secure nuclear deterrence through Juche. Foreign policy actions pursued by U.S. leaders have maintained the consistent message that the Asia-Pacific region cannot be stable unless North Korea is a non-nuclear state. Unfortunately, this calculus wrongly assumes that the key regional players agree and support this conclusion.

Noted East Asian security expert Dan Blumenthal observes that U.S. strategy to denuclearize North Korea has relied on two fundamentally flawed assumptions. First, the U.S. has maintained, “all parties [involved in negotiating] held North Korean denuclearization as their top priority.”[22] Second, the U.S. wrongly assumed “that North Korea could be talked into abandoning its nuclear program.”[23] In addition to these two flawed assumptions, it is important to note that the concept of strategic patience relies heavily on China as a key agent, both in terms of supporting U.S. actions aimed at denuclearizing North Korea and by supporting international sanctions. According to Michael Cohen, “Beijing has thus far decided that the benefits of a nuclear North Korea outweigh these costs…[and] China has made many pledges on North Korean sanctions in the past, but has always failed to honor them and to systematically enforce its commitments.”[24] Accordingly, the U.S. must re-evaluate its regional goals and strategic approach to develop a more effective strategy aimed at achieving a stable long-term solution.

Strategic Alignment with China: To successfully secure a stable Asia-Pacific region for the long run, U.S. policymakers must shift their focus from denuclearization to achieving regional stability. This requires the U.S. to acknowledge the fact that North Korea is a nuclear state and will remain one. U.S. leaders must focus on securing effective ways to ensure international management and oversight of the current North Korean nuclear program to achieve nuclear security and surety of their program. Moreover, the U.S. must align strategically with China to achieve regional stability and to lead efforts towards economic and political normalization between North Korea and the international community. This will help to undercut the regime’s anti-U.S. rhetoric and should help to foment domestic pressure for a more liberal system of governance in the long run.

Regional Cooperation & Economic Development: U.S. leaders must engage Japan and South Korea privately to make clear that the U.S. will honor strategic commitments, but that a new strategic engagement approach must be executed by all parties, led jointly between China and the U.S., to achieve long-term regional stability. Additionally, U.S. diplomats should work to foster the conditions necessary for unconditional multilateral dialogue between China, North Korea, South Korea, and Japan; aimed at normalizing relations between all parties, to include access to trade and opening the North Korean market to the region. Conversely, opening the North Korean economy to trade might eventually open opportunities to expose their citizenry to the global marketplace thereby planting the seeds for long-term transformation of the North Korean societal landscape.

Securing a Stable Asia-Pacific Region: U.S. negotiators must press North Korea to submit their nuclear program to UN oversight and to formally recognize South Korea as an independent and sovereign state. Accordingly, U.S. leaders should consider leveraging regional military reduction (exercises/force posture) as the primary bargaining chip to afford North Korea the opportunity to save-face. However, it must be made clear that any options aimed at reducing U.S. military presence requires all parties to agree to verifiable commitments aimed at halting further destabilizing actions by North Korea (e.g., nuclear testing, unannounced missile testing, the shelling of South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island, and the sinking of the Cheonan) and a commitment to recognize and honor the sovereignty of South Korea. Until a stable political relationship is achieved between these two governments, reunification of the Korean people remains an abstract and unachievable goal. In addition to leveraging U.S. regional military forces, U.S. diplomats should move forward with formally ending hostilities through a signed treaty thereby allowing North Korea to save face and U.S. negotiators to achieve their strategic goal for the region.

CONCLUSION

U.S. regional strategies aimed at halting North Korea’s nuclear ambitions have failed due to a fundamental misunderstanding of the cultural influences that drive North Korean decision-making. It is crucial to recognize that the Juche ideology has become so well inculcated throughout North Korean society that the people have become indoctrinated to accept Juche as their way of life. Juche has become a cultural phenomenon, almost a religion that instills national pride and honor. Juche is North Korea’s way of telling the world that despite the odds and the efforts to control their behavior, they are succeeding. Moreover, these strategies have failed due to a miscalculation of the strategic objectives associated with the Asia-Pacific. The inability of U.S. policymakers to align U.S. and Chinese strategic objectives has resulted in a series of miscalculated strategies that have failed to produce the desired results.

Current arguments claim that time has run out. With respect to achieving a non-nuclear North Korea, time ran out long ago. Achieving long-term stability requires policy makers to acknowledge that the more pressure placed on North Korean leaders to accept denuclearization as a prerequisite to any meaningful diplomatic discourse, the more blowback the U.S., allies, and regional partners will receive. More importantly, the continuation of pressure through sanctions has proven to embolden and strengthen the regime’s hold on its populace. Will this new strategy take time and patience to bear fruit? Yes. However, unlike strategic patience, the active pursuit of meaningful dialogue to achieve a stable region regardless of the nuclear status of North Korea has the highest potential of resulting in a lasting peace on the peninsula. Until U.S. policymakers adjust their strategic approach to achieve regional stability and prosperity as the strategic priority, the U.S. will continue to lose regional credibility in the Asia-Pacific and North Korea will remain the chief agent of regional instability.

Jason Knight is an officer in the Colorado Air National Guard and a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College where he participated in the advanced Joint Land, Air, Sea Strategy (JLASS) program. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Guard Bureau, U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: North Koreans citizens listen to the North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho's address at the U.N. General Assembly | Ed Jones, Getty Images

Notes:

[1] James Clapper, “A Conversation with James Clapper,” Council on Foreign Relations. http://www.cfr.org/intelligence/conversation-james-clapper/p38426.

[2] Barack Obama, U.S. National Security Strategy, 2015: 11. http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/63562.pdf.

[3] Donald Trump, U.S. National Security Strategy, 2017: 47. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

[4] Andrew Scobell and John Sanford, “North Korea’s Military Threat: Pyongyang’s Conventional Forces, Weapons of Mass Destruction, and Ballistic Missiles,” Strategic Studies Institute (2007): ix-3. http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB771.pdf.

[5] Homer T. Hodge, “North Korea’s Military Strategy,” The U.S. Army War College Quarterly Review, Strategic Studies Institute (2003): 70. http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/articles/03spring/hodge.pdf.

[6] Ibid., 71.

[7] Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Constitution of 1972 with Amendments through 1998: 3. https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Peoples_Republic_of_Korea_1998.pdf?lang=en; and Homer Hodge, “North Korea’s Military Strategy,” 68.

[8] Daniel Byman, “Keeping Kim: How North Korea’s Regime Stays in Power,” Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2010). http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/publication/20269/keeping_kim.html.

[9] Andrei Lankov, “Stiffer Sanctions on North Korea Won’t Work.” Bloomberg View (2016). https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-01-08/stiffer-sanctions-on-north-korea-won-t-work.

[10] OSD, “Military and Security Developments Involving the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea 2012,” A Report to Congress Pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 (2012): 1. http://archive.defense.gov/pubs/Report_to_Congress_on_Military_and_Security_Developments_Involving_the_DPRK.pdf.

[11] Jihwan Hwang, “Understanding North Korea’s Strategic Assessments in 2009 and the Reference Point Gap on the Korean Peninsula,” East Asia Security Initiative Working Paper 2 (2009): 4-5. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/137328/20091117176141.pdf.

[12] Hodge, North Korea’s Military Strategy, 72.

[13] Miles Maochun Yu, “China’s Strategic Calculations and North Korea’s Nuclear Gambit,” Stanford Hoover Institution (2016). http://www.hoover.org/research/chinas-strategic-calculations-and-north-koreas-nuclear-gambit.

[14] Jong Kun Choi, The Perils of Strategic Patience with North Korea, 63.

[15] Maochun Yu, China’s Strategic Calculations.

[16] David Straub, “North Korea Policy: Why the Obama Administration is Right and the Critics are Wrong,” The Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center and Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University (2016), 9.

[17] Eleanor Albert and Beina Xu, “The China-North Korea Relationship,” Council on Foreign Relations (2016). http://www.cfr.org/china/china-north-korea-relationship/p11097.

[18] Ibid.

[19] John Park, “North Korea’s Grip on China,” Harvard JFK School of Government (2005). https://www.hks.harvard.edu/news-events/news/news-archive/north-korea%22s-grip-on-china-the-more-china-wants-to-referee-conflicts-with-pyongyang,-the-more-power-it-gives-the-rogue-regime.

[20] Seigried Hecker, “What We really Know About North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons; and What we Don’t Yet Know for Sure,” The Council on Foreign Relations, Foreign Affairs, (2017). https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/north-korea/2017-12-04/what-we-really-know-about-north-koreas-nuclear-weapons.

[21] Ankit Panda, “The Hwasong-15: The Anatomy of North Korea's New ICBM; Is the Hwasong-15 the Apotheosis of North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Program?” The Diplomat, (2017). https://thediplomat.com/2017/12/the-hwasong-15-the-anatomy-of-north-koreas-new-icbm/.

[22] Dan Blumenthal, “Facing a Nuclear North Korea,” American Enterprise Institute (2005): 1. https://www.aei.org/publication/facing-a-nuclear-north-korea.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Michael Cohen, “China: Between U.S. Sanctions and North Korea,” The National Interest (2016): 1. http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/china-between-us-sanctions-north-korea-155511.