Angola, Clausewitz, and the American Way of War. John S. McCain IV. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 2017.

Angola, Clausewitz, and the American Way of War is an example of a book with great potential that falls short of its goal. In this slim volume, John S. McCain IV attempts to use the case of apartheid South Africa’s wars in Angola and Namibia during the 1980s as a positive example of Clausewitzian strategy in which political success (defeat of a Soviet and Cuban-backed onslaught) was achieved by devising effective ways and efficiently using limited means. He contrasts South African strategic acumen in stymying the efforts of the Southwest African People’s Organization and Cuban troops to take over Namibia with the lack of US strategy against Al Qaeda since 9/11 in the so-called global war on terrorism and the seemingly endless operations in Afghanistan and other locations in Southwest Asia and Africa. The author fails in his effort because he confuses the South African Defense Force’s (SADF’s) operational success with strategic brilliance and relies on one-sided evidence. The result is an impressive recounting of South Africa’s triumphs on the battlefields in Angola and Namibia which does not provide a satisfying bridge to strategic insights.

McCain’s admiration for the apartheid regime’s strategy relies too much on the narrative of its supporters and does not include other literature at the political and strategic level that would have led to a more accurate and balanced evaluation.[1] Instead of ensuring the survival of the apartheid regime, for example, Prime Minister-then-President P.W Botha’s “total strategy” of intervening in Angola and Namibia and suppressing domestic opposition inside South Africa backfired and led to a strengthening of international sanctions that helped bring the downfall of the regime and paved the way for President F.W. de Klerk to replace Botha and begin the transition to majority rule. In Namibia, moreover, the apartheid regime’s strategy of placing black allies in power was defeated in 1989, when the Southwest African People’s Organization swept to power in democratic elections. In the end, the apartheid leadership’s laager (circle the wagons) syndrome led to an excessive fear of a communist onslaught from Angola and strategic overreaction.

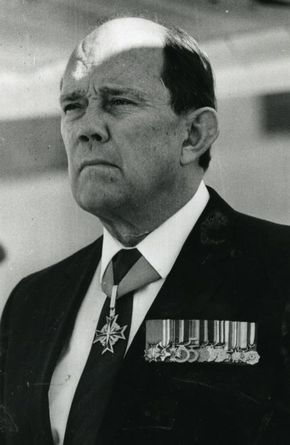

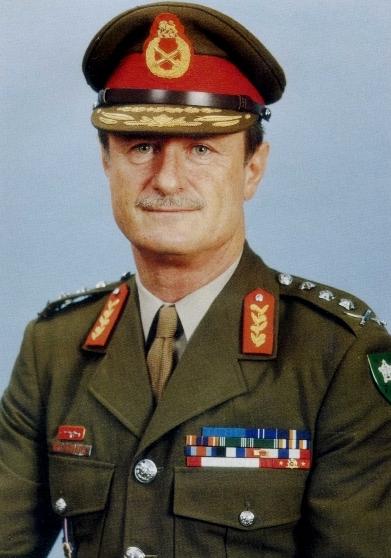

The problem with relying on one side of the literature in a case with which the author is not expert is the potential to commit errors and fall victim to bias, a potential evident in this work. The result is that McCain misunderstands the context and motivations behind South Africa’s strategy. He overstates the strategic importance of Angola and Namibia and its minerals to the Soviet bloc. The strategic minerals the Soviets and their allies coveted, such as chromium, manganese, and platinum, were not in those two countries but were in South Africa. In addition, the Soviets, South African Communist Party and the African National Congress considered Angola and Namibia to be mere stepping stones to the eventual takeover of South Africa. He claims the Southwest African People’s Organization (SWAPO) was “Marxist-Leninist” from its founding in 1960. However, SWAPO never declared itself to be Marxist-Leninist or proclaimed the goal of establishing a socialist state. Upon taking power through elections in 1990, they in fact established a free market democracy.[2] McCain claims South Africa “legitimized” SWAPO in 1977, but this only happened in 1989 after South Africa agreed to relinquish control of Namibia. The only action South Africa took in 1977 was agreeing to UN Security Council resolution 435 and the eventual goal of Namibian independence and South African withdrawal. He states that Prime Minister Balthazar Johannes Vorster was involved in devising the border war strategy, when it was Defense Minister P.W. Botha (soon to be prime minister and then state president) and General Magnus Malan (not Milan as the author misspells).[3] And the author states that Operation Moduler in Angola in 1987 was the epitome of civil-military dialogue. However, the dialogue was mainly among President Botha and Generals Malan and Geldenhuys and their closest advisors. There was no discussion with the whole cabinet, Ministry of Defense officials, or parliament. South Africa was criticized as a “security state” in which civilians had lost control over the military and secret police.[4] This is all amounts to a substantial misunderstanding of the political situation and the progress of the conflict.

McCain also misinterprets a number of military events. He mistakenly contends, for example, that the South African Air Force (SAAF) could not operate along the Namibia-Angola border because of Angolan Mig-23s. In fact, the SAAF was able to operate there from the 1960s through the late 1980s, though it waged tactical battles with the Angolan Air Force (and its Soviet bloc pilots) in the border area in the 1980s.[5] He also argues the paramilitary koevoet units and the 32nd special forces battalion constituted a strategic success that prevented Namibia from becoming a Marxist-Leninist state and allowed the democratic process to take shape. The human rights abuses of these units harmed the image of South Africa and its allies in Namibia, however, and the population in the area where the units and insurgents operated overwhelmingly voted for the Southwest African People’s Organization in the 1989 elections and rejected the forces that supported koevoet and the 32nd battalion.[6] This is powerful evidence against the author’s claims and interpretations.

In sum, McCain claims South African Defense Force (SADF) operations in Angola were both a strategic win and loss for South Africa. But the SADF’s presence in Angola was expensive and inconclusive and strengthened the hand of those in the United States and Europe who wanted stronger sanctions against South Africa. If South Africa had not intervened and the rebel National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) had been wiped out in 1987, the MPLA regime (the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola) would have gained control of most all of Angola. However, Soviet support for the Angolan regime and the Cuban expeditionary force was weakening in 1987 and 1988, and the negotiated settlement that led to the Cuban withdrawal in December 1989 and the independence of Namibia would have happened anyway.[7] The Botha regime took great risks in fighting battles that were not essential for its grand strategy of survival and that actually contributed to its downfall.

In seeking cases of outstanding strategy in Africa, the author could have chosen Paul Kagame’s strategy for the victory of his Rwandan Patriotic Front in the midst of the 1994 genocide and grand strategy for regime survival in the Great Lakes region thereafter. In the latter case, he directed his regime to coopt forces inside Rwanda, defeat adversaries in neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and exploit DRC resources to help modernize the country and win over much of the majority Hutu population.

In conclusion, McCain has usefully drawn our attention to a case that teaches by negative example. In the same way that the United States thought that anti-terrorism operations in Southwest Asia and Africa would contribute to strategic victory in the global war on terrorism, South African leaders believed that that the use of highly trained and mobile forces in operations against Cuban forces and insurgents would ensure the survival of white majority rule and domination over Namibia. The end result demonstrates the difficulty of devising a grand strategy in the face of great uncertainty and flux.

Stephen F. Burgess is a Professor of International Security Studies at the U.S. Air War College. He has published books and numerous articles, book chapters and monographs on Asian and African security issues, Peace and Stability Operations, and Weapons of Mass Destruction. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Image from the South African Border War (Steenkamp)

Notes:

[1] For example, Chester A. Crocker, High Noon in Southern Africa: Making Peace in a Rough Neighborhood, W.W. Norton & Co, 1993. Also, Piero Gleijeses Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991 (The New Cold War History), University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

[2] Colin Leys and John Saul, Namibia’s Liberation Struggle: The Two-Edged Sword, London: James Curry, 1995.

[3] Hilton Hamman, Days of the Generals: The untold story of South Africa’s apartheid military generals, Johannesburg, South Africa: Zebra Press, 2012.

[4] Chris Alden, Apartheid's Last Stand: The Rise and Fall of the South African Security State, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995.

[5] Peter Baxter, SAAF's Border War: The South African Air Force in Combat 1966-89, Solihull, UK: Helion & Co., 2013.

[6] William Lindeke, et al, “Namibia’s election revisited,” Politikon, Vol. 19, Iss. 2 (1992), pp. 121-138.

[7] Peter Vanneman, Soviet Strategy in Southern Africa: Gorbachev’s Pragmatic Approach, Palo Alto, Cal.: Hoover Institution Press, 1990