Vera Mironova and Craig Whiteside

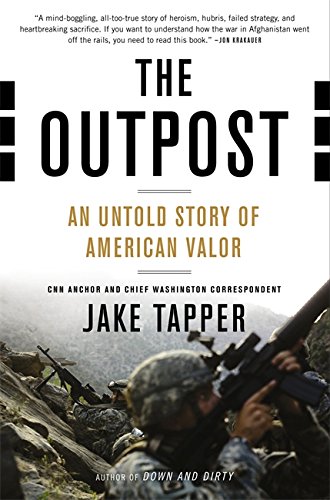

In Jake Tapper’s book The Outpost, a story about the occupation and eventual destruction of a military base in an obscure valley in Afghanistan, the author assures the reader he is not trying to convey any lessons learned. Instead, he wants to convey the experience of U.S. military members in Afghanistan fighting a war they—and, by the end of the book, the reader—can barely comprehend. He is being a bit modest here. No one writes a story like this, about the haunting events related to Combat Outpost Keating, without a desire for the reader to learn something from the heart-wrenching descriptions of valor, suffering, and duty. Tapper’s core questions are these: How do officers translate policy into strategy, and what can one say about the resulting operations and tactics? What do the events of Keating say about the links to strategy and policy, if anything? Was there ever any linkage at all?

Tapper’s only attempt at an explanation suggests the operational risk from the indefensibility of the outpost, a fact commented on by almost every experienced military person who stepped on or flew over the outpost, was overcome by “the deep-rooted inertia of military thinking.” Once these outposts were chosen, military decision-makers found themselves overcome by the physics of reversing this kind of decision, and later plans to abandon the outposts were often overcome by events with more priority, until it was too late. There were times when Command Outpost Keating worked just fine as part of the larger strategy…until it didn’t.

The need to evaluate the ever-changing strategic environment is not lost on many, although, as Tapper’s story relates, it is harder than one might think in complex environments. One example of this is the tactic of suicide bombing. It has been the subject of scholarly works and studies in multiple campaigns. For the U.S. military, suicide tactics have been an integral part of the threat environment for well over a decade. Familiarity with the concept generates a bit of complacency, but this is a false familiarity obscuring the reality that suicide bombing has changed in the last decade.

To spur a reevaluation of this tactic, and its operational and strategic implications, we published an article in the November/December issue of Military Review titled “Adaptation and Innovation with an Urban Twist: Changes to Suicide Tactics in the Battle of Mosul.” The article traces the historical evolution of the Islamic State’s use of suicide bombings (including operations under its previous guises), and how the organization has fused human resources, logistics, technological improvements, and tactics to execute a campaign that conducted over 1000 suicide operations in a recent 12-month period.

The Islamic State’s suicide bombing campaigns have changed in character in several ways over the last decade. Whereas the majority of perpetrators in this theater were once foreign immigrants to Iraq, today local Iraqis and Syrians conduct the majority of attacks. A decade ago, the Islamic State movement largely hit lightly defended civilian targets for maximum psychological and sectarian effects; today, they target conventional Iraqi military and police tactical units on the forward line of troops. Finally, Islamic State suicide bombing in the past was primarily a tool used to achieve strategic effects at the national, regional, and international level. In the recent caliphate period, with the Islamic State controlling and defending territory, suicide bombing has been marshaled for use in the operational realm, taking the form of coordinated counterattack waves against attacking forces.

Shi’ite Popular Mobilzation Forces (PMF) fighters carry the Islamic State militants flag downward after liberating the city of Al-Qaim, Iraq November 3, 2017. (Reuters)

The key driver for the Islamic State’s dramatic increase of suicide bombing capacity was their ability to control territory. The ability to influence populations, recruit locals for their campaign, and experiment with human resource policies to feed their suicide bombing machine was a game changer that produced the largest suicide campaign in history. This period of process innovation is worthy of study, even if the tactic fades from the news due to the drastic shift in the strategic environment for the Islamic State. The loss of contiguous physical territory, or the caliphate as the Islamic State describes it, will stress and frustrate its capacity to conduct large scale suicide bombing campaigns in the future—something already seen in the anti-climatic battle for Raqqa and al-Qaim.

Just like the Taliban’s successful adaptation to the early success of counterinsurgent forces at Keating, the Islamic State developed ways to counter their opponents’ advantages in technology through the use of their own suicide smart bombs. The urban environment’s unique challenges forced the Islamic State to transition from large devices traveling far from remote rural locations to small, mobile platforms with good camouflage and short drives to defeat the abundance of enemy observation, human and otherwise. Finally, the Islamic State’s overt experimentation in unmanned vehicles and drones documents the recognition that their access to human capital will be scarce again, and the group will be hard-pressed to waste precious experienced fighters in this manner. This highlights the different use of similar technologies by opponents; while the Islamic State develops unmanned platforms to keep fighters for use on the front line, advanced militaries in the West often use them to keep fighters from the fight.

How long will it be before the suicide campaign, long thought to be a tactic embedded with virtue signalling, becomes too much a luxury for insurgents who need every available body to fight against their powerful opponents, especially when technology provides an acceptable alternative? How long will it take before the Islamic State adapts its remotely piloted vehicles—which at present are prioritized for surveillance and dropping small-caliber ordnance on fixed positions—and begins using them as suicide devices capable of assassinating key leaders or destroying key command or logistics sites.?

Again, it is helpful for to compare these worrying advances with the successful attack on Keating in 2009. Despite the technological superiority of their opponent, the Taliban used basic weapons, tactics, and technologies that had not changed substantially from similar attacks on Soviet forces in the same region decades earlier—probably because their dominance in force ratio, intelligence, and advantages of terrain made innovation unnecessary. In contrast, during the desperate fight for Mosul this past year, Islamic State drone operators reconnoitered the urban defenses of elite Iraqi government forces, identified and communicated weak points for its suicide attacker, and then recorded the mission (in conjunction with covert media teams on the ground providing multiple viewpoints) for future propaganda release.

From this comparison, it is clear that what spurs adversary innovation in one theater may not be necessary in the other, and as a result changes in the character of the combat in one is happening at greater speeds than its counterpart. The reasons behind these differences, while difficult to discern, are worth further investigation. Strategic and operational decision makers need to pay close attention to the ever-changing character of war against different enemies—conventional or irregular—in distinctly different environments. This often means learning from our enemies.

Vera Mironova is a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland who has successfully defended her dissertation on the labor markets of insurgent groups in Syria. She is currently a researcher at Harvard’s Belfer Center.

Craig Whiteside is a professor of national security affairs at the Naval War College Monterey, and an associate fellow at the International Centre for Counterterrorism – The Hague (ICCT). The views expressed in this article are the authors' and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Islamic State Fighters in Raqqua, 2014. (Dabiq/Daily SIgnal)

Notes:

[1] Jake Tapper, The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (Back Bay Books, 2013).

[2] Tapper, p. 613.

[3] Mohammad Hafez, Suicide Bombers in Iraq (USIP, 2007); Mia Bloom, Dying to Kill: The Allure of Suicide Bombing (Columbia, 2007); Robert Pape, Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism (Random House, 2005).

[4] Craig Whiteside and Vera Mironova, “Adaptation and Innovation with an Urban Twist: Changes to Suicide Tactics in the Battle of Mosul,” Military Review (Fort Leavenworth: Nov-Dec 2017), pp. 2-9. Unless otherwise noted, the material cited in this article is documented in greater detail in Military Review.

[5] The period was late 2015 to late 2016.

[6] Robin Wright, “The Ignominious End of the ISIS Caliphate,” The New Yorker, Oct 17, 2017.

[7] While there are many possible reasons for the absence of innovation in this case, clear enemy advantages in this and many other cases reflect poorly on U.S. tactical and operational decision making. These bases were stationary examples of the much-maligned “presence patrols” that were eliminated in the Iraq theater after 2005, for similar reasons