Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific. Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson (eds). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014.

Guaranteed access is a chimera.[1]

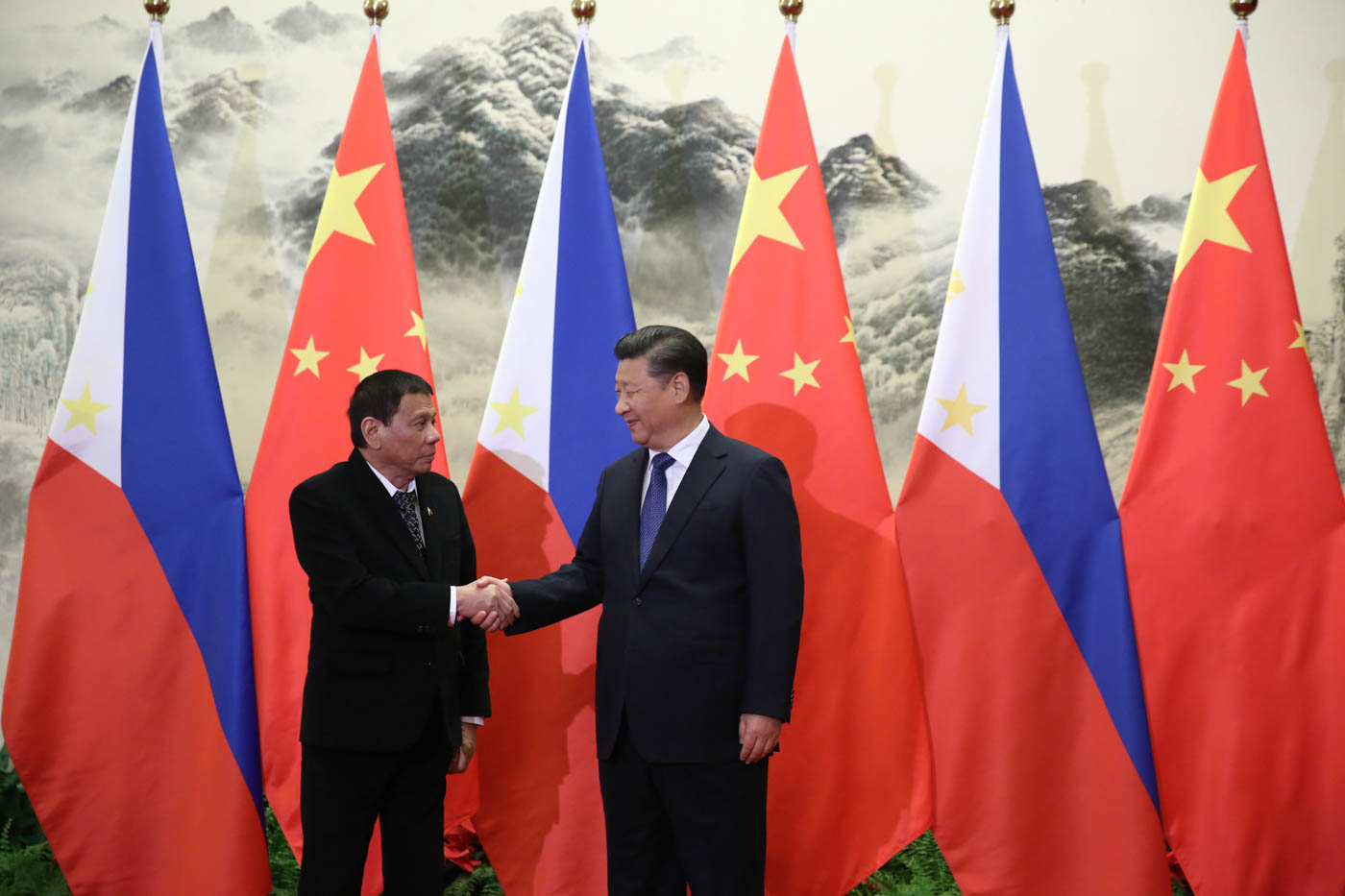

“The U.S. has lost,” President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines announced during a visit to Beijing in October of 2016, reinforcing a key lesson of Rebalancing U.S. Forces: that even long-standing alliance relationships are susceptible to political manipulation. Though this isn’t the first time the American/Filipino relationship has been called into question, it was only three years ago President Barack Obama and then-President Aquino signed an agreement to increase U.S. basing and combined military exercises in the Philippines. The uncertainty created by President Duterte’s remarks are exacerbated by the spread of violent non-state actors throughout the South Pacific, North Korea’s increasing nuclear and intercontinental ballistic missile capabilities, and China’s aggressive expansion in the South China Sea. These potential threats all underscore the need for the U.S. to reevaluate its basing in and access to the Asia-Pacific Region. Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific is an excellent place to begin.

Students and strategists alike will benefit from this volume edited by Carnes Lord, Professor of Strategic Leadership at the U.S. Naval War College and director of the Naval War College Press, and Andrew S. Erickson, Associate Professor at the Naval War College. This volume was incredibly timely, as the U.S. Navy released its “Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower” only a year after the former’s publication.

Forward basing prevents wars by deterring adversaries, demonstrates credible economic and military commitment to partners and allies, promotes stability, and most importantly, as the U.S. Navy’s Cooperative Strategy highlights, provides American leaders with options in times of uncertainty and crisis. Yet, as noted in Robert Rubel’s foreword, “[s]ince the onset of the Cold War, the study of basing has been more or less episodic and sporadic.”[2] Given the complexity and abundance of security problems in the region, now is a good time to undertake a fundamental reexamination of the American basing network in the Pacific.

Rebalancing U.S. Forces is a practical and useful guide that will benefit both practitioners and students equally. Although intended as a survey of U.S. basing, this work offers a history of American force posture in the Pacific, and provides excellent examples of the bureaucratic struggles, domestic politics, and the roles that individuals play in making basing decisions. It begins with an interesting examination of Guam’s role as an example to Washington on the costs and benefits of basing efforts in the Pacific. Rebalancing U.S. Forces then continues by considering American basing in allied and partner countries, including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Singapore.

Land basing is expensive, is vulnerable to enemy targeting, and is subject to political manipulation by the host nation.

The final chapter, exploring the role of sea basing, was particularly noteworthy for its careful explanation of the practical utility of sea basing in the Pacific. Basing forces and positioning deterrent capabilities in the international waters near a crisis area affords benefits similar to land basing while avoiding some of the pitfalls of basing forces forward in foreign countries. Land basing is expensive, vulnerable to enemy targeting, and subject to political manipulation by the host nation. Basing at sea is impermanent by design, presents a more difficult targeting problem to adversaries, and provides a potential answer to the problem of the domestic political concerns of fair-weather friends and uncertain neutrals. Although careful to avoid overselling the importance of sea basing, the author of this final chapter advanced the discussion and made an abstract concept substantially more concrete.

This volume understandably suffered from some limitations, mostly acknowledged by editors Lord and Erickson, who intended Rebalancing U.S. Forces to serve as a primer on U.S. basing in the Pacific. Practical considerations precluded an analysis of all the potential factors, countries, and considerations necessary to produce a comprehensive edition. As a survey, this edition focused narrowly on the Asian-Pacific countries or territories currently hosting U.S. forces. A more comprehensive follow up to Rebalancing U.S. Forces might also include a chapter on pre-negotiated access rights or “virtual basing” in countries of increasing importance such as Thailand, Indonesia, or Malaysia that could be established and disestablished rapidly during periods of crisis of conflict.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and People’s Republic of China President Xi Jinping shake hands prior to their bilateral meetings at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 20, 2016. (King Rodriguez/PPD)

Noticeably absent from this volume is a chapter devoted to U.S. basing and prepositioned stocks in the Philippines, an omission that, given the Philippines’ recent pivot to China, potentially warrants an updated and expanded edition. Despite the omission, in a particularly salient chapter on "U.S. Bases and Domestic Politics in Central Asia," Alexander Cooley examines the vulnerability of U.S. bases abroad to the pressures of domestic politics of their host governments and the potential for U.S. bases to cause “downstream political problems and obstacles.”[3] In another chapter, Chris Rahman demonstrates how Singapore’s stock rose and became an important security cooperation and logistics hub for the United States after the Philippines shuttered American bases in 1991.[4] Taken together, these excellent chapters underscore the importance of creating a regional network of expeditionary basing options and cooperative security facilities that can be expanded to meet emergent crises or rapidly abandoned when manipulation by host nation domestic politics outweighs the advantage gained through continued presence. Such an approach would provide strategic options in a critical region of the world and because other options exist, could mitigate the depth to which host nations could pressure American policymakers.

Though the work is primarily focused on the role naval and air forces and their relationship to the constellation of American bases in the Pacific, it does highlight the importance of land bases and cooperative security locations to project power. Future editions of this work would benefit from a more thorough examination of basing considerations, capabilities, and limitations for land forces of the United States.

To prepare intellectually for the future of armed conflict, in 2014 then-Major General H.R. McMaster recommended the study of war and warfare in “depth, breadth, and context.” Whereas introductory volumes such as American Defense Policy edited by Bolt, Coletta, and Shackelford and U.S. Defense Politics: The Origins of Security Policy edited by Sapolsky, Gholz, and Talmadge provide their readers breadth, where Rebalancing U.S. Forces shines is in the tremendous depth and contemporary context it provides. The strength of this volume is that it dives deep into a topic of contemporary importance and examines it in a regional context; “[a] global survey of the U.S. overseas military posture would inevitably be unwieldy or else superficial.”[5] Indeed, Carnes Lord and Andrew S. Erickson have found the appropriate balance between depth, breadth, and context.

...the capacity to win land wars in East Asia is not a necessary condition for maintaining strong military influence in the region.

What I found especially tantalizing in reading Rebalancing U.S. Forces was that it is based on the controversial premise that the capacity to win land wars in East Asia is not a necessary condition for maintaining strong military influence in the region.[6] “The key to America’s power projection in the region is control of the air and sea,” contributing authors Andrew Erickson and Justin Mikolay argue.[7] While this may be a case of where you stand depends on where you sit, as the volume was compiled by the Naval War College and published by the Naval Institute Press, I found the underlying assumption compelling and worth pursuing. Assuming this to be true, then, alternatives to costly and vulnerable land bases become particularly salient, especially in an era when potential adversaries pursue strategies that deny or degrade American access to the Pacific. In reflecting on what all conflicts have in common, however, I find that they are fought for control of territory, people, and resources. Moreover, the capacity to win land wars is essential to reassure allies and deter potential adversaries. In light of this, I find that the capacity to fight and win land wars in East Asia remains relevant, though I think reading Rebalancing U.S. Forces underscores the importance of jointness in the approach.

Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific is an essential introduction to U.S. basing in the Pacific for defense and intelligence analysts, military planners, and strategists, and is recommended reading for students of security studies. So important is the Indo-Asia-Pacific theater that by 2020 the U.S. Navy expects to have as many as 60% of its ships and aircraft based in the region.[8] It has become, as Hillary Clinton described in 2011, a key driver of global politics.[9] It is evident after reading this volume that for the United States to remain strategically relevant, to demonstrate credible commitment to its allies and offer credible deterrents to its adversaries, it must rebalance and reexamine its basing network in the Asia/Pacific. Rebalancing U.S. Forces is an excellent start to that reexamination.

Christopher Mercado is an officer in the U.S. Army with extensive experience between Iraq, Afghanistan, Africa, and the West Bank and has served as a Division Planner for the Pacific Pathways Exercise. Chris earned his M.A. in Security Studies from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in 2016 as a Downing Scholar of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. The views expressed in this review are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Utility Landing Craft (LCU-1635) travels to unload excess ammunition off of the amphibious assault ship USS Tarawa (LHA 1). (U.S. Navy Photo/Photographer’s Mate Airman Apprentice Bryan Niegel)

Notes:

[1] Lord, Carnes, and Andrew S. Erickson, eds. Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2014, 150.

[2] Ibid., xii.

[3] Ibid., 195.

[4] Ibid., 119.

[5] Ibid., 5.

[6] Ibid., 16.

[7] Ibid.

[8] United States Navy Department. A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower. Washington, DC, 2007, 11.

[9] Clinton, Hillary R. "America's Pacific Century." Foreign Policy, November 2011