China’s economic growth over the last 40 years has been extraordinary, lifting millions of Chinese out of poverty and making China among the most economically powerful nations in the world. Since Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening-Up policies, China has modernised to a startling extent. However, this growth has been uneven and has caused severe inequality across the country. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is often seen as promoting China’s influence across the world, but this is not its only purpose. This article looks at how the Belt and Road Initiative is being used as one measure to transform some of the poorest regions of China, and how despite this, China is failing to address some of the issues in its most volatile areas.

The province of Xinjiang has existed as a separate civilisation since the 7th century and has always sat uneasily within China’s margins. It borders the former Soviet states of Central Asia, making its repeated bids for independence particularly unsettling for China in the light of the break-up of the Soviet Union. Xinjiang’s main ethnic group, the Uighurs, are a Turkic people who predominantly practice Sufism. In an attempt to dilute the Uighur influence, the government has encouraged Han-majority peoples to settle in Xinjiang, which has led to the Uighur population falling from over 90% of Xinjiang in 1949 to around 40% in 2018.[1] Regional unrest only increased, however.

Ethnic Uighur women grab a riot police officer as they protest in Urumqi, in China's far west Xinjiang province, on July 7, 2009. (Peter Parks/AFP/Getty)

Following years of minor skirmishes, tensions boiled over in 2009 when 200 people, mainly Han Chinese, died in Uighur-led riots in Urumqi. President Hu Jintao was forced to return from a G8 summit to deal with the incident. This was an embarrassing moment for the ruling party. How could Hu persuade the world that China was ready to take on greater global power when he didn’t even appear to have control over a sixth of his own land mass? His response was unequivocally brutal. The Uighurs were subject to increased persecution, with Islamic activities repressed and citizens encouraged to inform on one another if they breached the new laws. Unsurprisingly, this did little to stabilise the area.

The Chinese attitude to the Uighurs over the last thirty years demonstrates the opportunistic shifting of goals that often characterises China’s approach to geopolitics.[2] After the end of the Cold War and the break-up of the Soviet state, China echoed the narrative of separatism in Xinjiang and painted the Uighurs as an independence group seeking to break up the country.[3] From the US perspective, China was the last major bastion of Communism in a changing world and Xinjiang another oppressed state seeking freedom. The US formally supported the Uighurs as an oppressed people and put pressure on China to improve their situation.[4] China was uncomfortable with this level of scrutiny but it was ten years before it could rewrite the narrative.

As the US War on Terror began, China opportunistically dropped the separatist argument and began to relate Xinjiang’s problems to organised terrorism. In 2002, it linked the Uighurs to Al Qaeda in a State Council report.[5] Recognising the value of Chinese support to counter Al Qaeda in Afghanistan and the surrounding area, the US dropped its condemnation of the Uighur oppression.[6] The truth of the Uighur-Al Qaeda link is harder to get at. The main insurgent group, the Uighur East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), is not listed as a current or former terrorist group by either the US Department of State or the EU, nor are any other Uighur organisations. The UN does list East Turkestan Islamic Movement as a terrorist group associated with Al Qaeda and imposes sanctions accordingly. However, the movement’s leader has repeatedly denied any links to Al Qaeda, and Bin Laden never acknowledged the group as being affiliated. Castets believes China fabricated or exaggerated the Al Qaeda link to generate international condemnation in the post-9/11 atmosphere of suspicion, which allowed China to continue its repression of the Uighurs without Western opposition.[7]

As the US drew down troop numbers in Afghanistan and focused on national reconstruction rather than conflict, its need for Chinese support diminished. At the same time, Donald Trump was developing an anti-China stance in his Presidential election campaign that only intensified after he took office. “Remember, China is not a friend of the United States!” he proclaimed on Twitter. At the same time, other nations—including the UK—were becoming increasingly concerned about the human rights situation in Xinjiang. Reports began to emerge of so-called correction centres for Uighurs who were breaching any of the restrictive local laws against Islamic activities. China continues to deny that it is imprisoning Uighurs without trial, calling the camps re-education centres and transformation through education schools. These euphemisms do little to hide the stories of brutality, violence, and brainwashing that emerge. Despite this increasing condemnation and the decreasing credibility of the Uighurs’ links with Islamic terror organisations, China seems to be stepping up repression. In March 2019, one respected researcher estimated that up to 1.5 million Uighurs were being held in these camps. Out of a population of 8 million Uighurs in the region, this is startling.

China is increasingly presenting itself as a responsible member of the world order, and in a modern globalised world it is hard to hide such activities. It therefore seems incredible that this can be happening, but China’s views on human rights are fundamentally different from those of the West. China sees individual rights as a dangerous Western concept that jeopardises the good of the collective.[8] Xinjiang’s Uighurs, in the Chinese view, are damaging the cohesion of China, and their actions must be corrected.

As well as ethnic and religious differences, China believes that poverty and inequality are to blame for increasing militancy.[9] In his Report at the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress, Xi Jinping set out his priorities for regional investment, including ethnic minority populations, border areas, poor areas and “old revolutionary base areas,” in a clear reference to Xinjiang. China has adopted a two-pronged approach to improving Xinjiang’s financial position. Firstly, a proportion of all revenue generated by Xinjiang’s businesses must now remain in the region to be reinvested in local development. But this development only helps China if Xinjiang is more widely connected, which is where the Belt and Road Initiative comes in. Raffaello Pantucci, Director of International Security Studies at the Royal United Services Institute think-tank, told me that he felt Xinjiang’s stability was one of the single most important issues around the initiative.[10] For China, increasing wealth in coastal regions and major cities matters little if a landlocked province a seven-hour flight from Beijing can destabilise the whole country. Especially now that Xi has abandoned any pretence of democracy, it is important to show the world that he can maintain control over his own country. A repeat of the 2009 riots would be a disaster.

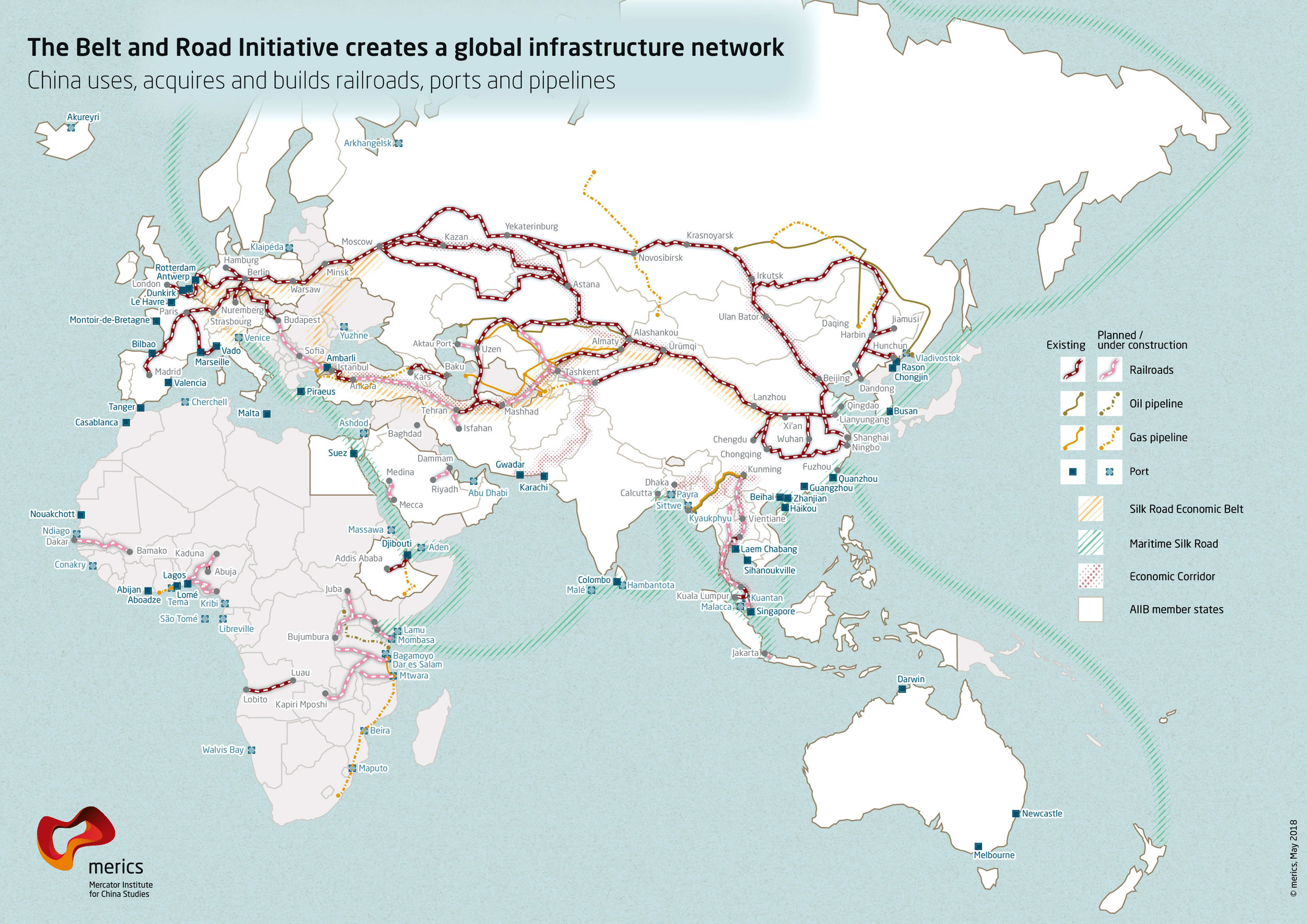

Fortunately for China, Xinjiang has two qualities that make it an ideal candidate for development investment. It is rich in oil, gas, and coal, and it is geographically adjacent to Central Asia. The same geographical position that gives China concern that it might seek independence also makes it the perfect hub for Chinese exports via the Belt and Road Initiative. Not only will a more prosperous Xinjiang be less likely to seek independence and foment insurgency, but using the initiative to increase the wealth of Central Asian countries and make them beholden to China for this largesse creates a non-democratic buffer zone between China and the West. It is no surprise that the Belt and Road Initiative was announced in Astana, given that Xinjiang’s longest border is with Kazakhstan.[11]

In many cases, the Belt and Road Initiative has built on existing infrastructure. The oil refinery at Dushanzi in Xinjiang has been a critical hub since the late 1990s, taking oil from across Central Asia to supply China’s growing energy needs. Kashgar was designated a Special Economic Zone in 2001, twelve years before the Belt and Road Initiative began.[12] But the initiative is bringing all these projects together under one banner and adding some new ones. One of its headline ventures is the creation of six new economic land corridors, including the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, linking Xinjiang to the port of Gwadar in Pakistan. This direct trade route is expected to bring “economic and national security dividends” to Xinjiang by making the province into a trading hub.[13] How effective this will be remains to be seen. Although a major distribution hub is being developed at the small town of Khorgos on the Xinjiang-Kazakhstan border, the tax-free shopping centres on the Kazakhstan side are largely empty, and the local market is still the heart of commerce. Traders flocked there initially, but were disappointed; the area is sparsely populated, and the 2015 currency devaluation by Kazakhstan meant that few could afford to shop there. The benefits for local people remain elusive.

Even if these benefits emerge, there is a risk that efforts to decrease poverty in Xinjiang will just increase inequality. The Chinese dismissal of individual rights may prove to be its downfall if it cannot improve living standards for everyone as a way of tackling extremism. Few seem to be concerned about this. When asked at a conference how the Belt and Road Initiative would improve the lives of the poorest people in Xinjiang and Central Asia who still didn’t have cars or jobs, Joseph Chan—Professor of political theory at the University of Hong Kong and Visiting Professor at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton—was dismissive. To the bewilderment of the Western members of the panel and audience, he shrugged and suggested they now had better roads to walk in.[14]

Xinjiang remains a thorn in China’s side. Although the Belt and Road Initiative is aimed at improving living standards and thereby decreasing unrest in the province, there is little evidence so far that this is working. At the same time, the increasing repression of the Uighur people and the growing evidence of human rights abuses is leading to widespread international condemnation. Through its actions in Xinjiang, China risks alienating the rest of the world just at a time when it is seeking to expand into it.

Rebecca Warren is a warfare officer in the Royal Navy, currently undertaking a Master’s by Research at King’s College London. The views expressed in this article the author’s own and do not reflect the position of the Royal Navy, the Ministry of Defence, or the UK Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping waves as he leaves after a news conference at the closing of the Belt and Road Forum at Yanqi Lake on the outskirts of Beijing. (AP)

Notes:

[1] Tom Miller. China’s Asian Dream. (London: Zed Books, 2018): 60.

[2] Francois Jullien, translated by Janet Lloyd. A Treatise on Efficacy. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004), 33.

[3] Russell Ong, "China's relations with Central Asia" in The Ashgate Research Companion to Chinese Foreign Policy, ed Emilian Kavalski (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2012), 244

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Michael Clarke, ed. Terrorism and Counter-terrorism in China. (London: C Hurst & Co, 2018): 3.

[7] Remi Castets, “The Uyghurs in Xinjiang - The Malaise Grows.” China Perspectives, no 49 (2003).

[8] Henry Kissinger. World Order. (n.p.: Penguin, 2015), 230.

[9] Peter Cai. "Understanding China's Belt and Road Initiative." Lowy Institute for International Policy, 2017, 7.

[10] Raffaello Pantucci, RUSI Director of International Security Studies. Interview with author, January 11, 2019.

[11] Miller, China’s Asian Dream, 30.

[12] Ibid., 70.

[13] Cai, Understanding, 7.

[14] Joseph Chan, Speech, “The Belt and Road Initiative: Bringing the East and West Together?” Conference from SOAS China Institute, London, November 26, 2018.