The Russian National Security Strategy establishes its military defense and status as a world power as two of its most enduring strategic security interests.[1] It further notes, the top threats to its national security include North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), foreign militaries’ encroachment on its borders, and armed conflicts in neighboring countries.[2] In response to these threats, Russia’s military doctrine prioritizes national defense, strategic deterrence, and the mobilization and deployment of forces in “dangerous strategic directions.”[3] Given these interests, threats, and military priorities, the string of military outposts of the former Soviet Union from the Baltic to the Black Sea can serve either as defensive or offensive means. Assessing the defensive and offensive dispositions of these outposts aids in evaluating their role and utility in Russia’s military strategy.

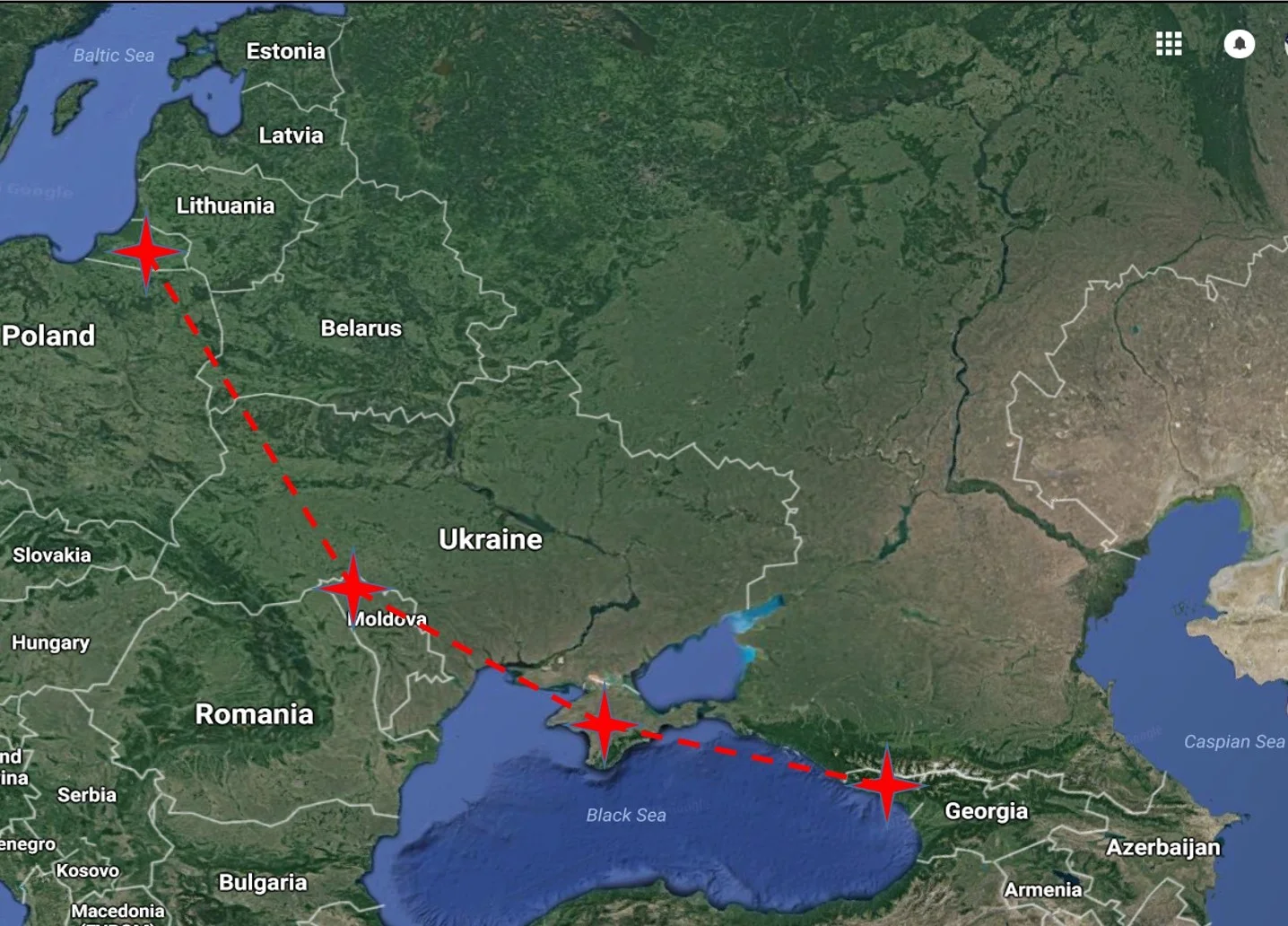

The military outposts forming this rampart formerly resided within the boundaries of the Soviet Union. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation has incorporated the military outposts peacefully or by force of arms. The Baltic anchor of this strategic rampart, Kaliningrad, is the headquarters of the Russian Baltic Fleet, and despite its geographic position between Poland and Lithuania, is internationally recognized as an enclave of Russia. The other outposts reside outside of the Russian Federation yet are occupied by the Russian military, specifically Transnistria in the Republic of Moldova, Crimea in the Ukrainian Republic, and ending in the eastern Black Sea at Abkhazia and Southern Ossetia in the Republic of Georgia (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: String of post-Soviet Russian Military Outposts

Assessing the defensive and offensive dispositions of these military outposts provides insights into strategic choices of the Russian military. The geography of the outposts in Figure 1 initiates the assessment. Do these outposts form a defensive trip-wire on Russia’s vulnerable and oft-invaded western front? Or are these outposts simply lily-pads which support offensive force projection platforms?

Generally it is problematic distinguishing between the defensive and offensive capabilities at the tactical level.[4] A Russian infantry or armor brigade can both gain territory offensively or hold territory defensively. However, the ability to project military forces strategically requires an array of logistics capabilities to both mobilize forces in mass and sustain the deployment. Specifically, capabilities to support the transportation of personnel, ammunition, supplies, and equipment through a combination of road, rail, air, or sea networks are central to force projection.[5] Subsequently, an assessment the nature of the military forces for each Russian outpost must pay particular attention to the array of logistics capabilities.

Kaliningrad

The northern anchor of this Russian string of outposts is the Baltic enclave of Kaliningrad. It is home to the Baltic Sea Fleet at Baltiysk Naval base, naval air bases in Chkalovsk and Donskoy, and bases supporting its naval infantry, artillery, and missile forces.[6] According to the Russian Ministry of Defense, its primary mission is to protect the economic zone, ensure the safety of navigation, and support foreign policy through port calls, exercises, and peacekeeping.[7]

The capabilities of the Kaliningrad Baltic Fleet enable offensive force projection. Amphibious ships and naval infantry complement its array of surface and sub-surface combatants. Transportation aviation, while moderately sized, are supported by naval air bases and an air force base at the civilian airport. A detailed description of the forces arrayed in the Baltic Fleet are noted in Appendix 1.

As a power projection platform, Kaliningrad is rapidly becoming “one Europe’s most militarized places.”[8] Additional naval infantry and mechanized troops, aircraft, and air defense forces deployed to Kaliningrad in 2015. As recent as October 2016, the Russian Defense Ministry announced the deployment of nuclear-capable Iskander short-range ballistic missiles to the region.[9]

Transnistria

The next Russian outpost is in the Transnistria region of the Republic of Moldova. Transnistria is a long-standing, post-Soviet military outpost of Russia. Since Moldova’s declaration of independence, its autonomous region of Transnistria has been the home of the formerly-Soviet 14th Guards Army. The region was the site of a two-year civil war between pro-Russian elements and the Moldovan defense forces from 1990-1992.[10] A cease-fire ended the civil war but transitioned the area into a long-standing frozen conflict. Along with an established framework to continue negotiating a settlement to the conflict, Russian “peacekeepers” remain in Transnistria.

The Russian Ministry of Defense notes military peacekeepers have stayed in the region since the 1992 “Convention on Principles of Peaceful Settlement of the Armed Conflict in the Transnistrian Region of the Republic of Moldova.”[11] Their primary mission is noted to establish a safe area between belligerents. An additional mission includes the security of remnants of Soviet armaments depots in Transnistria. The Moldovan government continues to reiterate requests that Russia completely withdraw its stockpiles of armaments, its military forces, and transition the peacekeeping mission into a United Nations-mandated civil police mission.[12]

Russian forces in Transnistria are estimated to be 1,500 personnel, of which 380 are in the peacekeeping battalion. They are organized into two motorized rifle battalions of one hundred tanks and armored personnel carriers, and approximately ten Mi-24 Hind and Mi-8 Hip helicopters.[13] Nonetheless, despite the remaining stockpiles of Soviet-era armaments, these forces do not possess logistical capabilities to mobilize forces and sustain strategic force projection.

Crimean Peninsula

The next outpost is the Crimean Peninsula. Previously leasing military bases from Ukraine, the Russian military seized control in 2014 following the Euromaidan protest in Kiev and the ouster of President Yanukovych. On March 16, 2014, Russia annexed the Crimea after a referendum where Crimeans voted to join the Russian Federation. Despite its lack of international recognition, Crimea continues to base a large contingent of the Russian military and the headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Russian soldiers guard the entrance to the Ukrainian military base in Perevalne, Crimea | Ivan Sekretarev/AP

The Black Sea Fleet’s capabilities enable offensive force projection. Amphibious ships and naval infantry complement its array of surface and sub-surface combatants arrayed at naval bases at Donuzlav Bay, Chornomorskoye, Balaklava, and headquartered at Sevastopol. Transportation aviation, while moderately sized, are supported by several air bases at Belbek, Gvardeyskaya, Novofedorivka, Kirovsky, and Yevpatoriya. Since the annexation, additional Russian forces deployed to Crimea including a combined-arms army reinforced with aviation and air defense. A detailed description of the forces arrayed in the Black Sea Fleet are noted in Appendix 2.

Even before the 2014 annexation, Crimea served as a power projection platform. Elements of the Black Sea Fleet, including its flagship Moskva, blockaded the Republic of Georgia during the 2008 war in the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[14] Additionally, the fleet’s amphibious landing ships disembarked a motorized rifle brigade at the port of Ochamchira in support of Abkhazian forces.[15]

These actions in 2008 would secure Russia’s southern-most anchor of the string of outposts in both Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Admittedly, the 2008 Georgian War was not the first time Russian troops were stationed in these regions. Russian peacekeepers routinely deployed in various strengths since Georgia’s post-independence conflicts in the early 1990s.

Russian forces in Abkhazia and South Ossetia are estimated to be 7,000 personnel. In Abkhazia, there is one motorized rifle brigade of forty T-90 main battle tanks, 120 infantry fighting vehicles and armored personnel carriers, air defense forces, and attack helicopters.[16] In South Ossetia, there is one motorized rifle brigade of forty T-72 main battle tanks, 120 infantry fighting vehicles and air defense forces.[17] Despite the formidable size of the Russian military in Georgia, they lack the logistical capabilities for force projection beyond their operational area.

Synthesis

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian military retained this string of military outposts primarily through the force of arms. Ongoing 1990s-era peacekeeping missions secure outposts in Moldova and Georgia where ground troops – ranging from some battalions in Moldova to brigades in Georgia – operate from static defensive positions. Soviet-era naval bases in Kaliningrad and Crimea remain as power projection platforms for the Russian Navy.

Returning to the questions posed earlier, do these outposts form a defensive trip-wire or are they lily-pads supporting offensive force projection platforms? The Russian Navy’s Baltic and Black Sea fleets are by their nature power projection capabilities and have been used in this manner in recent conflicts. However, their logistical – and particularly transportation – capabilities are moderate and require reinforcement to support strategic deployments of significant magnitude. The peacekeeping operations in Moldova and Georgia lack the capabilities to project power beyond their operational area.

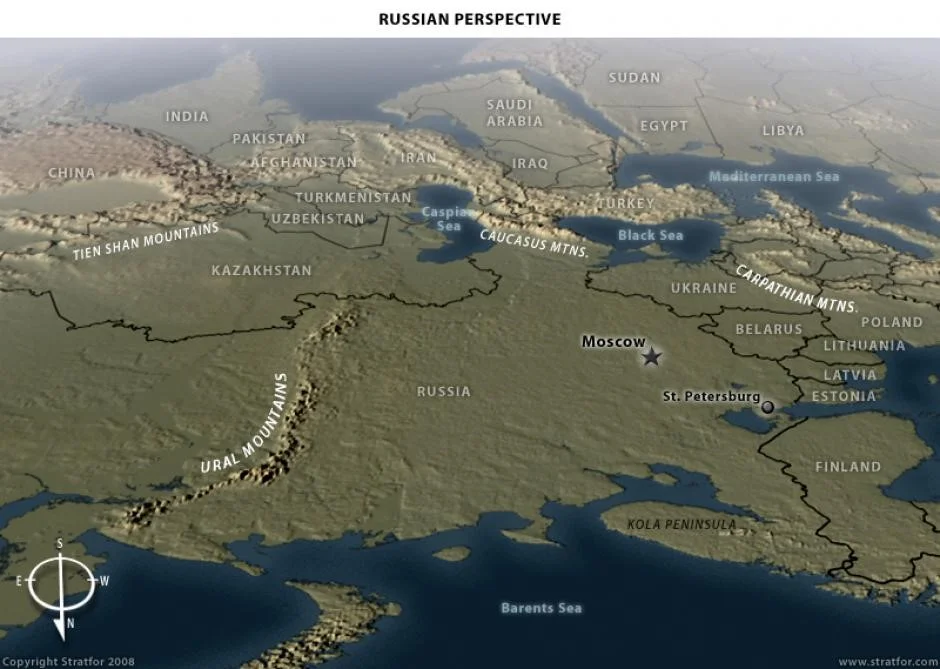

These outposts provide strategic depth on the edge of the Russian plains once protected by a buffer of Soviet satellite states (Figure 2).[18] The peacekeeping missions in Moldova and Georgia provide a means to remain deployed forward on the edge of the Carpathian and Caucasus ranges under the auspices of conflict prevention.[19] The naval bases allow access to sea lines of communication beginning in the Baltic and Black Seas and are home to air defense capabilities that include early detection.

Figure 2: Russian Perspective (source STRATFOR)

This brief assessment yields questions for further research. Would the Russian military like these outposts to serve as lily-pads but lack the economic means for them to be successful? If they were to convert these tripwires to lily-pads, how hard would it be and how much would it entail? Ultimately, is the evidence of the primary purpose of these outposts as tripwires or does it reflect a general weakness of the Russian military position?

John DeRosa is a civilian serving on the Joint Staff, a U.S. Army veteran, and a member of the Military Writers Guild. He is National Defense University's U.S. European Command Scholar researching Russian nuclear narratives and a doctoral student at George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.

Header image: A column of Russia's T-90 tanks rolls at the Red Square in Moscow, on May 9, 2013, during Victory Day parade. (Photo: YURI KADOBNOV/AFP/Getty Images)

Appendices

Appendix 1: Baltic Fleet

Source: (2016) “Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” The Military Balance. London: Institute for Strategic Studies,116:1, 196.

Appendix 2: Black Sea Fleet

Source: (2016) “Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” The Military Balance. London: Institute for Strategic Studies, 116:1, 198.

Notes:

[1] (December 31, 2015). The National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from: http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/OtrasPublicaciones/Internacional/2016/Russian-National-Security-Strategy-31Dec2015.pdf.

[2] (January 5, 2015,). Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from http://www.scribd.com/doc/251695098/Russia-s-2014-Military-Doctrine#scribd.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Charles L. Glaser and Chaim Kaufmann, “What Is the Offense-Defense Balance and How Can We Measure It?” International Security, 22, no. 4 (Spring 1998): 44-82.

[5] Langford, Gary D. (May 2004). “Power Projection Platforms: An Essential Element of Future National Security Strategy.” U.S. Army War College Research Project. Retrieved from: http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA423647.

[6] “Baltic Fleet.” Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from: http://eng.mil.ru/en/structure/forces/navy/associations/structure/forces/type/navy/baltic/about.htm.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Tony Wesolowsky (June 18, 2015). “Kaliningrad, Moscow's Military Trump Card.” RFERL. Retrieved from: http://www.rferl.org/a/kaliningrad-russia-nato-west-strategic/27079655.html

[9] (October 10, 2016). “Poland says Russian Iskander missiles deployment 'inappropriate response' to NATO activity.” TASS. Retrieved from: http://tass.com/world/905362.

[10] Bobick, M. S. (2014). “Separatism Redux: Crimea, Transnistria, and Eurasia's de facto States.” Anthropology Today, 30(3), 3-8.

[11] “Peacekeeping operation in Transnistria.” Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from: http://eng.mil.ru/en/mission/peacekeeping_operations/more.htm?id=10336232@cmsArticle.

[12] (April 4, 2016). “Moscow and Chisinau are unable to agree on military presence in Transnistria.” Sputnik. Retrieved from: https://sputniknews.com/politics/201604041037443990-ministers-talks-military/.

[13] (2016) “Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” The Military Balance. London: Institute for Strategic Studies, 116:1, 201.

[14] (August 10, 2008). “Russian Navy ships approach Georgia's sea border." Sputnik. Retrieved from: https://sputniknews.com/russia/20080810115932226/.

[15] Dmitry Gorenburg (December 2008). “The Russian Black Sea Fleet After the Georgia War.” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 48, Harvard University. Retrieved from: http://www.ponarseurasia.org/sites/default/files/policy-memos-pdf/pepm_048.pdf.

[16] (2016) “Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” The Military Balance. London: Institute for Strategic Studies, 116:1, 201.

[17] The Military Balance, 201.

[18] (April 15, 2012). “The Geopolitics of Russia: Permanent Struggle.” STRATFOR. Retrieved from: https://www.stratfor.com/analysis/geopolitics-russia-permanent-struggle.

[19] Alexander Sokolov (December 1997). “Russian Peace-Keeping Forces in The Post-Soviet Area.” Chapter 8 in Restructuring the Global Military Sector Volume I: New Wars. PINTER: London and Washington.